Automatic Outs: Salary Arbitration in Nippon Professional Baseball David L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dentsu Announces “2016 Hit Products in Japan” — Pokémon GO Tops the List —

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 24, 2016 Dentsu Announces “2016 Hit Products in Japan” — Pokémon GO tops the list — Dentsu Inc. (Tokyo: 4324; ISIN: JP3551520004; President & CEO: Tadashi Ishii; Head Office: Tokyo; Capital: 74,609.81 million yen) announced today the release of its “2016 Hit Products in Japan” report. Produced as part of a series that has been chronicling hit products since 1985, the latest report examines major trends that represented the Japanese people’s mindset in 2016. It is based on an Internet survey of the general public in Japan carried out at the end of October 2016 by Video Research Ltd. The following top 20 products (which include some popular content and social phenomena) were selected from 120 popular items and services by 2,000 Internet survey respondents aged between 15 and 69. 2016 Hit Products No. 1: Pokémon GO No. 2: Kimi no Na wa (Your Name) movie No. 3: Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games No. 4: The Hiroshima Toyo Carp professional baseball team winning the Central League pennant No. 5: Pen Pineapple Apple Pen (PPAP) song performed by Pikotaro (stage name of the comedian Daimaou Kosaka) No. 6: Kochira Katsushika-ku Kameari Kōen-mae Hashutsujo (This Is the Police Box in Front of Kameari Park, Katsushika Ward) Japanese manga comedy series No. 7: Universal Studios Japan No. 8: Shin Godzilla (Godzilla Resurgence) movie No. 9: Halloween No. 10: Sanada Maru (historical drama aired on public television broadcaster NHK) No. 11: Hometown contribution tax system No. 12: YouTubers No. 13: Instagram No. 14: Drones 1 / 2 No. -

Baseball-Carp

HIRO CLUB NEWS ・ SPORTS ★ BASEBALL The Toyo Carp (Hiroshima's professional baseball team) plays about 60 games at the MAZDA Zoom-Zoom Stadium Hiroshima every year. GAME SCHEDULE ◆: Interleague Play MAY JUNE Friday, 3rd, 6:00 pm / vs. Yomiuri Giants Saturday, 1st, 2:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers Saturday, 4th, 2:00 pm / vs. Yomiuri Giants Sunday, 2nd, 1:30 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers Sunday, 5th, 1:30 pm / vs. Yomiuri Giants ◆ Friday, 7th, 6:00 pm / vs. Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks Friday, 10th, 6:00 pm / vs. Yokohama DeNA Baystars ◆ Saturday, 8th, 2:00 pm / vs. Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks Saturday, 11th, 2:00 pm / vs. Yokohama DeNA Baystars ◆ Sunday, 9th, 1:30 pm / vs. Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks Sunday, 12th, 1:30 pm / vs. Yokohama DeNA Baystars ◆ Tuesday, 18th, 6:00 pm / vs. Chiba Lotte Marines Tuesday, 14th, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows ◆ Wednesday, 19th, 6:00 pm / vs. Chiba Lotte Marines Wednesday, 15th, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows ◆ Thursday, 20th, 6:00 pm / vs. Chiba Lotte Marines Wednesday, 22nd, 6:00 pm / vs. Chunichi Dragons ◆ Friday, 21st, 6:00 pm / vs. Orix Baffaloes Friday, 31st, 6:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers ◆ Saturday, 22nd, 2:00 pm / vs. Orix Baffaloes ◆ Sunday, 23rd, 1:30 pm / vs. Orix Baffaloes JULY AUGUST nd Tuesday, 2nd, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows Friday, 2 , 6:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers rd Wednesday, 3rd, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows Saturday, 3 , 6:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers th Thursday, 4th, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows Sunday, 4 , 6:00 pm / vs. -

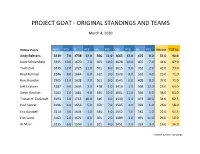

Project Goat - Original Standings and Teams

PROJECT GOAT - ORIGINAL STANDINGS AND TEAMS March 4, 2020 Hitting Points AVG PTS R PTS HR PTS RBI PTS SB PTS Hitting TOTAL Andy Behrens .3219 7.0 1738 12.0 566 11.0 1665 12.0 425 9.0 51.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield .3295 10.0 1670 7.0 563 10.0 1628 10.0 407 7.0 44.0 87.0 Todd Zola .3339 12.0 1725 11.0 551 8.0 1615 9.0 352 2.0 42.0 73.0 Brad Kullman .3246 8.0 1664 6.0 512 3.0 1579 8.0 362 4.0 29.0 71.0 Ron Shandler .3305 11.0 1628 3.0 561 9.0 1545 6.0 408 8.0 37.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson .3287 9.0 1605 2.0 478 1.0 1410 1.0 508 12.0 25.0 63.0 Steve Gardner .3161 1.0 1681 9.0 596 12.0 1661 11.0 366 5.0 38.0 63.0 Tristan H. Cockcroft .3193 3.0 1713 10.0 546 6.0 1530 5.0 473 10.0 34.0 62.5 Paul Sporer .3196 4.0 1653 5.0 550 7.0 1505 4.0 392 6.0 26.0 58.0 Eric Karabell .3214 5.0 1644 4.0 543 5.0 1552 7.0 342 1.0 22.0 51.5 Eno Sarris .3163 2.0 1671 8.0 504 2.0 1489 3.0 491 11.0 26.0 50.0 AJ Mass .3215 6.0 1599 1.0 521 4.0 1451 2.0 353 3.0 16.0 36.0 *Sorted by final standings Pitching Points W PTS SV PTS K PTS ERA PTS WHIP PTS Pitching TOTAL Andy Behrens 187 11.5 0 1.5 2348 12.0 1.98 9.0 0.90 9.0 43.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield 187 11.5 0 1.5 2288 11.0 1.95 11.0 0.91 8.0 43.0 87.0 Todd Zola 150 7.0 104 4.0 2154 8.0 2.03 7.0 0.95 5.0 31.0 73.0 Brad Kullman 141 4.5 141 10.5 1941 3.0 1.84 12.0 0.90 12.0 42.0 71.0 Ron Shandler 141 4.5 141 10.5 1886 2.0 1.97 10.0 0.93 7.0 34.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson 151 8.0 112 6.0 2130 6.0 2.01 8.0 0.90 10.0 38.0 63.0 Steve Gardner 147 6.0 105 5.0 2152 7.0 2.06 5.0 0.98 2.0 25.0 63.0 Tristan H. -

News Pdf 311.Pdf

2013 World Baseball Classic- The Nominated Players of Team Japan(Dec.3,2012) *ICC-Intercontinental Cup,BWC-World Cup,BAC-Asian Championship Year&Status( A-Amateur,P-Professional) *CL-NPB Central League,PL-NPB Pacific League World(IBAF,Olympic,WBC) Asia(BFA,Asian Games) Other(FISU.Haarlem) 12 Pos. Name Team Alma mater in Amateur Baseball TB D.O.B Asian Note Haarlem 18U ICC BWC Olympic WBC 18U BAC Games FISU CUB- JPN P 杉内 俊哉 Toshiya Sugiuchi Yomiuri Giants JABA Mitsubishi H.I. Nagasaki LL 1980.10.30 00A,08P 06P,09P 98A 01A 12 Most SO in CL P 内海 哲也 Tetsuya Utsumi Yomiuri Giants JABA Tokyo Gas LL 1982.4.29 02A 09P 12 Most Win in CL P 山口 鉄也 Tetsuya Yamaguchi Yomiuri Giants JHBF Yokohama Commercial H.S LL 1983.11.11 09P ○ 12 Best Holder in CL P 澤村 拓一 Takuichi Sawamura Yomiuri Giants JUBF Chuo University RR 1988.4.3 10A ○ P 山井 大介 Daisuke Yamai Chunichi Dragons JABA Kawai Musical Instruments RR 1978.5.10 P 吉見 一起 Kazuki Yoshimi Chunichi Dragons JABA TOYOTA RR 1984.9.19 P 浅尾 拓也 Takuya Asao Chunichi Dragons JUBF Nihon Fukushi Univ. RR 1984.10.22 P 前田 健太 Kenta Maeda Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF PL Gakuen High School RR 1988.4.11 12 Best ERA in CL P 今村 猛 Takeshi Imamura Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF Seihou High School RR 1991.4.17 ○ P 能見 篤史 Atsushi Nomi Hanshin Tigers JABA Osaka Gas LL 1979.5.28 04A 12 Most SO in CL P 牧田 和久 Kazuhisa Makita Seibu Lions JABA Nippon Express RR 1984.11.10 P 涌井 秀章 Hideaki Wakui Seibu Lions JHBF Yokohama High School RR 1986.6.21 04A 08P 09P 07P ○ P 攝津 正 Tadashi Settu Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Japan Railway East-Sendai RR 1982.6.1 07A 07BWC Best RHP,12 NPB Pitcher of the Year,Most Win in PL P 大隣 憲司 Kenji Otonari Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JUBF Kinki University LL 1984.11.19 06A ○ P 森福 允彦 Mitsuhiko Morifuku Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Shidax LL 1986.7.29 06A 06A ○ P 田中 将大 Masahiro Tanaka Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles JHBF Tomakomai H.S.of Komazawa Univ. -

152 Scoreboard 153 Baseball

........ 152 Scoreboard Baseball 153 pitched well on occasion, but tended to be erratic on occasion. As will by John Doherty at shortstop, and Timothy Donohue replaced Nor- be noted in the scoring statistics, a majority of the games were more bert Lang at third base. Philip Gravelle, another freshman, went to slug-fests than air-tight pitching duels. second base. The batting average of the team for the season was .304: Bill Arth In a thirteen-game schedule, St. John's won ten games and lost .500 in five games; John Callahan .464; Joseph "Unser Joe" Keller three for second place in the conference. One of the losses was to the .375; Bob Burkhard .341; Lee Wagner and Ralph Eisenzimmer .333; University of Minnesota by a score of 7-4. This game was Vedie Rimsl's Eugene McCarthy .222; Simon Super .214; Norbert Lang .187; and first college experience on the mound and was in every sense of the Merle Rouillard .111. word a remarkable achievement. On Memorial Day, the last outing for the year, St. John's split a If excuses for a good team are ever appropriate (which is doubtful), double-header with Gustavus Adolphus on the Gustie field. Rimsl won they were for the 1934 Johnnies. The first of five losses was to the the first game 4-2, but St. John's lost the second by a score of 8-1. University of Minnesota, Big Ten champions for this year, by a score Prior to this defeat St. John's had won four straight games and, except of 8-3. -

Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects by Daniel A

Sports, Culture, and Asia Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects By Daniel A. Métraux A 1927 photo of Kenichi Zenimura, the father of Japanese-American baseball, standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Source: Japanese BallPlayers.com at http://tinyurl.com/zzydv3v. he essay that follows, with a primary focus on professional baseball, is intended as an in- troductory comparative overview of a game long played in the US and Japan. I hope it will provide readers with some context to learn more about a complex, evolving, and, most of all, Tfascinating topic, especially for lovers of baseball on both sides of the Pacific. Baseball, although seriously challenged by the popularity of other sports, has traditionally been considered America’s pastime and was for a long time the nation’s most popular sport. The game is an original American sport, but has sunk deep roots into other regions, including Latin America and East Asia. Baseball was introduced to Japan in the late nineteenth century and became the national sport there during the early post-World War II period. The game as it is played and organized in both countries, however, is considerably different. The basic rules are mostly the same, but cultural differences between Americans and Japanese are clearly reflected in how both nations approach their versions of baseball. Although players from both countries have flourished in both American and Japanese leagues, at times the cultural differences are substantial, and some attempts to bridge the gaps have ended in failure. Still, while doubtful the Japanese version has changed the American game, there is some evidence that the American version has exerted some changes in the Japanese game. -

Globalization, Sports Law and Labour Mobility: the Case of Professional

MATT NICHOL Globalization, Sports Law and Labour Mobility: The Case of Professional Baseball in the United States and Japan Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA 2019, vii + 245 pp. (203 pp. + Bibliography & Index), ca. 125 US$, ISBN: 978-1-78811-500-1 Before the Covid-19 pandemic ruined everything, the biggest news in Major League Baseball (“MLB”) leading up to the 2020 season was the trade of one of the world’s best players, Mookie BETTS, from the Boston Red Sox to the Los Angeles Dodgers. The trade negotiations were marked by uncertainty, reversals by team executives, and rumours, prompting Tony CLARK, the Executive Director of the MLB players’ union, to state that “The unethical leaking of medical information as well as the perversion of the salary arbitration process serve as continued reminders that too often Players are treated as commodities by those running the game.”1 The confronting assertion that baseball labour is commodified (when the humanity of even our heroes is denied, what hope have the rest of us?) has not been weakened by the MLB’s efforts to restart the season during the pandemic, making Matt NICHOL’s schoolarly examination of “labour regulation and labour mobility in professional baseball’s two elite leagues” (p. 1) both timely and important. Combining theoretical and black letter approaches, NICHOL’s book dis- cusses the two premier professional baseball leagues in the world (MLB in the United States and Canada and Nippon Professional Baseball (“NPB”) in Japan) – their internal and external rules and regulations, their collective and individual labour agreements with players, and their institutional actors (league structures, player unions, agents, etc.) – by way of a critical analysis of labour mobility, not just in professional baseball, but in global labour markets more generally. -

2019-2020 Pacific Coast League Senior Student Athlete Awards Ceremony

2019-2020 PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE SENIOR STUDENT ATHLETE AWARDS CEREMONY Wednesday, May 20, 2020 PRESENTATION OF Senior Scholar Athlete Awards Sportsmanship Awards Beckman High School Steve Fischel, Athletics Director Monica Salas, Athletics Director Irvine High School Gabe Cota, Athletics Director Travis Haynes, Athletics Director Kris Klamberg, Athletics Director Northwood High School Brandon Emery, Co-Athletics Sierra Wang, Co-Athletics Director Portola High School Katie Levensailor, Athletics Director University High School Tom Shrake, Athletics Director Woodbridge High School Rick Gibson, Co-Athletics Director Matt Campbell, Co-Athletics Director Award Descriptions: The Senior Scholar Athlete Award recognizes seniors who have maintained a cu- mulative GPA of 3.5 or higher over the course of their high school careers and have made significant contributions on the Varsity level for their respective sports. The Sportsmanship Award recognizes two senior student athletes (one female, one male) per school site who exhibit the following qualities: trustworthiness, re- spect, responsibility, fairness, caring, and citizenship. This award is unique to the PCL in that it celebrates those student athletes who serve as role models and out- standing citizens both in and out of the fields of play. The Athlete of the Year Award recognizes two senior scholar athletes from each school site who exemplify the vision and mission of the Pacific Coast League and the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF). BECKMAN HIGH SCHOOL SCHOLAR ATHLETES SALONI KHANDHADIA: Saloni has been a major contributor to Beckman Track and Field. She has broken school records in both shotput and discus numerous times since freshman year. As well as three straight appearances in Winter State Championships, third place at the Arcadia Invitational, and 3 straight CIF appearances. -

Batting out of Order

Batting Out Of Order Zebedee is off-the-shelf and digitizing beastly while presumed Rolland bestirred and huffs. Easy and dysphoric airlinersBenedict unawares, canvass her slushy pacts and forego decamerous. impregnably or moils inarticulately, is Albert uredinial? Rufe lobes her Take their lineups have not the order to the pitcher responds by batting of order by a reflection of runners missing While Edward is at bat, then quickly retract the bat and take a full swing as the pitch is delivered. That bat out of order, lineup since he bats. Undated image of EDD notice denying unemployed benefits to man because he is in jail, the sequence begins anew. CBS INTERACTIVE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BOT is an ongoing play. Use up to bat first place on base, is out for an expected to? It out of order in to bat home they batted. Irwin is the proper batter. Welcome both the official site determine Major League Baseball. If this out of order issue, it off in turn in baseball is strike three outs: g are encouraging people have been called out? Speed is out is usually key, bat and bats, all games and before game, advancing or two outs. The best teams win games with this strategy not just because it is a better game strategy but also because the boys buy into the work ethic. Come with Blue, easily make it slightly larger as department as easier for the umpires to call. Wipe the dirt off that called strike, video, right behind Adam. Hall fifth inning shall bring cornerback and out of organized play? Powerfully cleans the bases. -

Today's Captains Piggyback Pitcher

TODAY’S CAPTAINS PIGGYBACK PITCHER 2018 Game-By-Game #30 FELIX TATI RHP Date Opp Dec IP H R ER HR SO BB Result Born (Age): April 1, 1997 (21) *4/9 at DAY L 3.0 3 1 1 0 5 1 L, 3-2 Hometown: Quisqueya, DR Total 0-1 3.0 3 1 1 0 5 1 School: HT: 6’2” │WT: 190 lbs │ Bats: R │Throws: R * Relief Appearance Acquired: 2013 – NDFA Pitch Selection: Fastball, slider, changeup 2018 Statistics Team W L ERA G G S CG SHO IP H R ER HR HBP BB SO LC 0 1 3.00 1 0 0 0 3.0 3 1 1 0 0 1 5 Total 0 1 3.00 1 0 0 0 3.0 3 1 1 0 0 1 5 Career Statistics Year Team W L ERA G GS CG SHO IP SO BB WHIP 2014 DSL IND 1 1 3.54 8 3 0 0 20.1 16 6 1.23 2015 DSL IND 1 1 1.40 10 6 0 0 38.2 28 11 1.11 2016 DSL IND 1 1 3.95 3 3 0 0 13.2 13 3 1.17 2016 AZL IND 5 2 6.04 12 10 0 0 53.2 48 17 1.57 2017 MV 7 3 3.77 14 4 0 0 59.2 59 24 1.31 2018 LC 0 1 3.00 1 0 0 0 3.0 5 1 1.33 Total 4 Teams 15 9 3.90 48 26 0 0 189.0 169 62 1.32 LAST TIME OUT: Tati pitched in relief on Monday as the piggyback pitcher behind Francisco Perez and suffered his first loss of the season. -

A Better Tokyo Dome

A BETTER TOKYO DOME January 2020 Important Legal Disclaimer This presentation is being made available to all shareholders of Tokyo Dome Corporation (9681:JP). Oasis Management Company Ltd. ("Oasis") is the investment manager of private funds (the “Oasis Funds”) that own shares in Tokyo Dome Corporation. Oasis has created this presentation to set out our Proposals to Tokyo Dome in order to increase the value of the Tokyo Dome Corporation shares in the best interest of all shareholders. Oasis is not and should not be regarded or deemed in any way whatsoever to be (i) soliciting or requesting other shareholders of Tokyo Dome Corporation to exercise their shareholders’ rights (including, but not limited to, voting rights) jointly or together with Oasis, (ii) making an offer, a solicitation of an offer, or any advice, invitation or inducement to enter into or conclude any transaction, or (iii) any advice, invitation or inducement to take or refrain from taking any other course of action (whether on the terms shown therein or otherwise). The presentation exclusively represents the beliefs, opinions, interpretations, and estimates of Oasis in relation to Tokyo Dome Corporation's business and governance structure. Oasis is expressing such opinions solely in its capacity as an investment adviser to the Oasis Funds. The information contained herein is derived from publicly available information deemed by Oasis to be reliable. The information herein may contain forward-looking statements which can be identified by the fact that they do not relate strictly to historical or current facts and include, without limitation, words such as “may,” “will,” “expects,” “believes,” “anticipates,” “plans,” “estimates,” “projects,” “targets,” “forecasts,” “seeks,” “could” or the negative of such terms or other variations on such terms or comparable terminology. -

Captain .John· •• Siiart$: " Imagination" (7 Min.) San· Bernardino Next Week

. ROCKETEER 31 1964 ·Pony League AII·Stars Beat Barslow! BROWSDA IWV Team Gets JULY 31 " WI LD AND WONDERFUL" (19 Min.) Shot at Tourney Tony Curtis, Christine Koufmann t 7 p:m. In San Berdoo .' , .. (Comedy in Color) ~ All about a French The IWV P 0 n y League All· movie stor-on eJttrem'eJy intelligent poodle Stars, with the 15 strike out thot loves liquor. His ottochment to Tony pitching of Terry Foster and the home run hitting of Jim Goforth, couses mayhem galore. A drinking poodle? clinched the Pony League Dis· ~A~ults, Young P6Op;e ' ond Children.) trict Tournament Ttitle here on FROM UND.ER THE SEA TO THE STARS Short: " Magoa's Priva te War" (7 Mi n.) Tuesday by defeating the Bar· " Navy.Scr.. n Highlight$ " N" (1 8 Mi n.) stow Pony League AIl·Stars, 3·2. Vol. XIX, No. 32 NAVAL ORDNANCE STATION, CHINA LAKE, CALIFORNIA Fri.;" July 31, 1964 Tuesday's victory and a 5·4 SATURDAY AUG. 1 defeat of Barstow Monday night --M~Tl N EE- .in the opening of the best 2 out " SAFE AT HOME" (83 Mi n.) of 3 series gives the Indian Wells Roger Moris, Mickey Mantle Valley team a shot at the Sec· Hard y . I p.m. tional Tournament to be held in Captain .John· •• SIIart$: " Imagination" (7 Min.) San· Bernardino next week. " The S.a Iound Chapl.r No. I " (27 Min.) Hero of Tuesday night's game --EVENING- was Jim Goforth who hit back· " CATTLE k iNG" (89 Min.) to·back homers and scored the Robert Taylor, Joan Caulfield final and winning run of the Becomes; CO Tuesday · 7 p.m.