For Switchgrass Cultivated As Biofuel in California, Invasiveness Limited by Several Steps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Combustion Characteristics of Four Perennial Energy Crops (Arundo Donax, Cynara Cardunculus, Miscanthus X Giganteus and Panicum Virgatum)

2nd World Conference on Biomass for Energy, Industry and Climate Protection, 10-14 May 2004, Rome, Italy EVALUATION OF THE COMBUSTION CHARACTERISTICS OF FOUR PERENNIAL ENERGY CROPS (ARUNDO DONAX, CYNARA CARDUNCULUS, MISCANTHUS X GIGANTEUS AND PANICUM VIRGATUM) Jonas Dahl & Ingwald Obernberger Institute of Resource Efficient and Sustainable Systems, Graz University of Technology, Inffeldgasse 25, A - 8010 Graz, Austria, Tel.: +43 (0)316 481300, Fax: +43 (0)316 481300 4; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The perennial crops giant reed, switchgrass, miscanthus and cardoon were investigated in laboratory- scale and pilot-scale combustion test runs. Laboratory-scale test runs were conducted in a fixed bed pot reactor monitoring the temperature in the fuel bed and the release of gaseous components while pilot-scale test runs where conducted in a 150 kWth rotating grate fired combustion plant measuring formed emissions of CO, NOX, SO2, HCl, and particulates as well as performing deposit probe measurements. The results revealed that the high concentration of ash and slag forming elements such as Si, K and Ca cause severe problems regarding slagging if not specially considered during combustion. Moreover, high concentrations of N are another challenge regarding measures in order to avoid high emissions of NOx. Moreover, also HCl and SO2 emissions are considerably higher compared to wood fuels due to the higher concentrations of Cl and S in these fuels. Keywords: biomass characteristics, biomass conversion, cynara cardonculus, giant reed, switchgrass, miscanthus 1 INTRODUCTION combustion unit (nominal boiler capacity 150 kWth) were carried out with larger amounts (2-4 tons) of Due to the limited availability of wood fuels, in pelletised switch grass and chopped giant reed and southern Europe, high yield energy crops could give an chopped miscanthus (MI). -

Advanced Biofuel Policies in Select Eu Member States: 2018 Update

© INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON CLEAN TRANSPORTATION POLICY UPDATE NOVEMBER 2018 ADVANCED BIOFUEL POLICIES IN SELECT EU MEMBER STATES: 2018 UPDATE This policy update provides details on the latest measures that select European ICCT POLICY UPDATES Union (EU) member states, namely Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, SUMMARIZE Sweden, and the United Kingdom, are taking to support advanced alternative fuels. REGULATORY AND OTHER EU POLICY BACKGROUND DEVELOPMENTS In 2018, the European Union (EU) set its climate and energy objectives for 2030. RELATED TO CLEAN They included a greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction of at least 40% and a minimum of a TRANSPORTATION 32% share of renewable energy consumption across all sectors.1 GHG emissions in the WORLDWIDE. European transportation sector have declined by only 3.8% since 2008, compared to an 18% decrease, or more, in all other sectors, indicating that the decarbonization of transportation should be a priority for the future.2 Biofuels are one of the options considered to increase renewable energy and decrease the carbon intensity of the transportation sector. Through the use of directives and national legislation, the EU has incentivized both the adoption of conventional food-based biofuels and advanced biofuels, which are made from non-food feedstocks. Such incentives date to 2009, when the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) mandated that by 2020, 10% of energy used in the transportation sector should come from renewable energy sources (RES).3 In 2015, the RED was 1 Jacopo Giuntoli, Final recast Renewable Energy Directive for 2021-2030 in the European Union, (ICCT: Washington, DC, 2018), https://www.theicct.org/publications/final-recast-renewable-energy-directive- 2021-2030-european-union 2 EUROSTAT (Greenhouse gas emissions by source sector (env_air_gge), accessed November 2018), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat. -

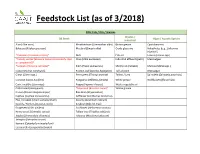

Feedstock List (As of 3/2018)

Feedstock List (as of 3/2018) FOG: Fats / Oils / Greases Wastes / Oil Seeds Algae / Aquatic Species Industrial Aloe (Aloe vera) Meadowfoam (Limnanthes alba) Brown grease Cyanobacteria Babassu (Attalea speciosa) Mustard (Sinapis alba) Crude glycerine Halophytes (e.g., Salicornia bigelovii) *Camelina (Camelina sativa)* Nuts Fish oil Lemna (Lemna spp.) *Canola, winter (Brassica napus[occasionally rapa Olive (Olea europaea) Industrial effluent (palm) Macroalgae or campestris])* *Carinata (Brassica carinata)* Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Shrimp oil (Caridea) Mallow (Malva spp.) Castor (Ricinus communis) Peanut, Cull (Arachis hypogaea) Tall oil pitch Microalgae Citrus (Citron spp.) Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) Tallow / Lard Spirodela (Spirodela polyrhiza) Coconut (Cocos nucifera) Pongamia (Millettia pinnata) White grease Wolffia (Wolffia arrhiza) Corn, inedible (Zea mays) Poppy (Papaver rhoeas) Waste vegetable oil Cottonseed (Gossypium) *Rapeseed (Brassica napus)* Yellow grease Croton megalocarpus Oryza sativa Croton ( ) Rice Bran ( ) Cuphea (Cuphea viscossisima) Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) Flax / Linseed (Linum usitatissimum) Sesame (Sesamum indicum) Gourds / Melons (Cucumis melo) Soybean (Glycine max) Grapeseed (Vitis vinifera) Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa) Tallow tree (Triadica sebifera) Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) Calophyllum inophyllum Kamani ( ) Lesquerella (Lesquerella fenderi) Cellulose Woody Grasses Residues Other Types: Arundo (Arundo donax) Bagasse -

Bioenergy and Invasive Plants: Quantifying and Mitigating Future Risks

Invasive Plant Science and Management 2014 7:199–209 Bioenergy and Invasive Plants: Quantifying and Mitigating Future Risks Jacob N. Barney* The United States is charging toward the largest expansion of agriculture in 10,000 years with vast acreages of primarily exotic perennial grasses planted for bioenergy that possess many traits that may confer invasiveness. Cautious integration of these crops into the bioeconomy must be accompanied by development of best management practices and regulation to mitigate the risk of invasion posed by this emerging industry. Here I review the current status of United States policy drivers for bioenergy, the status of federal and state regulation related to invasion mitigation, and survey the scant quantitative literature attempting to quantify the invasive potential of bioenergy crops. A wealth of weed risk assessments are available on exotic bioenergy crops, and generally show a high risk of invasion, but should only be a first-step in quantifying the risk of invasion. The most information exists for sterile giant miscanthus, with preliminary empirical studies and demographic models suggesting a relatively low risk of invasion. However, most important bioenergy crops are poorly studied in the context of invasion risk, which is not simply confined to the production field; but also occurs in crop selection, harvest and transport, and feedstock storage. Thus, I propose a nested-feedback risk assessment (NFRA) that considers the entire bioenergy supply chain and includes the broad components of weed risk assessment, species distribution models, and quantitative empirical studies. New information from the NFRA is continuously fed back into other components to further refine the risk assessment; for example, empirical dispersal kernels are utilized in landscape-level species distribution models, which inform habitat invasibility studies. -

Plant Fact Sheet

United States Department of Agriculture NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Forestry Technical Note No. MT-27 April 2006 FORESTRY TECHNICAL NOTE ______________________________________________________________________ Performance Evaluations of Herbaceous Vegetation on Disturbed Forestland in Southeastern Montana Robert Logar, State Staff Forester Larry Holzworth, Plant Material Specialist Summary Information for seeding herbaceous vegetation following forestland disturbance was identified as a conservation need in southeastern Montana. The herbaceous vegetation could be used to control soil erosion, stabilize disturbed sites, manage noxious weeds and provide forage. The Fulton Ranch field evaluation planting (FEP) was established in November 1995 on a disturbed forestland site in southeastern Montana to study the adaptation, performance and use of various grass species. The site, a Ponderosa pine/Idaho fescue habitat-type, had received a light to moderate burn from a wildfire that occurred in August 1994 and was logged the following spring. Nineteen evaluation plots were established to test seventeen different accessions of grasses; two control (unseeded) plots were established. Each plot was one-quarter of an acre in size. Seeded species included ‘Sherman’ big bluegrass, ‘Latar’ orchardgrass, ‘Paiute’ orchardgrass, ‘Manska’ pubescent wheatgrass, ‘Oahe’ intermediate wheatgrass, ‘Rush’ intermediate wheatgrass, ‘Dacotah’ switchgrass, ‘Forestberg’ switchgrass, 9005308 mountain brome, ‘Regar’ meadow brome, ‘Redondo’ Arizona fescue, ‘Whitmar’ beardless wheatgrass, ‘Goldar’ bluebunch wheatgrass, M-1 Nevada bluegrass, ‘Killdeer’ sideoats grama, ‘Pierre’ sideoats grama, and ‘Pryor’ slender wheatgrass. An evaluation of several species for seeding road systems was also conducted as part of this FEP. Road surface, cut and fill slopes were seeded with ‘Luna’ pubescent wheatgrass, ‘Covar’ sheep fescue, ‘Durar’ hard fescue, ‘Critana’ thickspike wheatgrass, ‘Sodar’ streambank wheatgrass, and ‘Rosana’ western wheatgrass. -

Ecology and Management of Arundo Donax, and Approaches to Riparian Habitat Restoration in Southern California

ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF ARUNDO DONAX, AND APPROACHES TO RIPARIAN HABITAT RESTORATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA. Gary P. Bell The Nature Conservancy of New Mexico, 212 E. Marcy Street, Suite 200, Santa Fe, NM 87501 USA Abstract By far the greatest threat to the dwindling riparian resources of coastal southern California is the alien grass species known as Arundo donax. Over the last 25 years the riparian forests of coastal southern California have become infested with A. donax which has spread by flood-fragmentation and dispersal of vegetative propagules. Arundo donax dramatically alters the ecological/successional processes in riparian systems and ultimately moves most riparian habitats towards pure stands of this alien grass. By current estimates there are tens of thousands of acres of A. donax along the major coastal drainage systems of southern California, including the Santa Ana, Santa Margarita, Ventura, Santa Clara, San Diego, and San Luis Rey rivers. The removal of A. donax from these systems provides numerous downstream benefits in terms of native species habitat, wildfire protection, water quantity and water quality. Introduction Arundo L. is a genus of tall perennial reed-like grasses (Poaceae) with six species native to warmer parts of the Old World. Arundo donax L. (giant reed, bamboo reed, giant reed grass, arundo grass, donax cane, giant cane, river cane, bamboo cane, canne de Provence), is the largest member of the genus and is among the largest of the grasses, growing to a height of 8 m (Fig. 1). This species is believed to be native to freshwaters of eastern Asia (Polunin and Huxley 1987), but has been cultivated throughout Asia, southern Europe, north Africa, and the Middle East for thousands of years and has been planted widely in North and South America and Australasia in the past century (Perdue 1958, Zohary 1962). -

Planting and Managing Switchgrass As a Biomass Energy Crop

United States Technical Note No. 3 Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Materials Planting and Managing Program September 2009 Switchgrass as a Biomass Energy Crop Issued September 2009 Cover photo: Harvesting dormant switchgrass for biofuel (Photo by Don Tyler, University of Tennessee) The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, re prisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should con tact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720–2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795–3272 (voice) or (202) 720–6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Preface The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conserva tion Service (NRCS) Plant Materials Program has been involved in the col lection, evaluation, selection, increase, and release of conservation plants for 76 years. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) was quickly recognized as one of the key perennial grasses for soil conservation following the dust bowl era of the 1930s. The first named switchgrass cultivar, ‘Blackwell’, was released in 1944 by the NRCS Manhattan, Kansas, Plant Materials Center (PMC) in cooperation with the Kansas Agriculture Experiment Station. -

Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J

HO-79 Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J. Nash, Mary L. Witt, Linda Tapp, and A. J. Powell Jr. any ornamental grasses are available for use in resi- Grasses can be purchased in containers or bare-root Mdential and commercial landscapes and gardens. This (without soil). If you purchase plants from a mail-order publication will help you select grasses that fit different nursery, they will be shipped bare-root. Some plants may landscape needs and grasses that are hardy in Kentucky not bloom until the second season, so buying a larger plant (USDA Zone 6). Grasses are selected for their attractive foli- with an established root system is a good idea if you want age, distinctive form, and/or showy flowers and seedheads. landscape value the first year. If you order from a mail- All but one of the grasses mentioned in this publication are order nursery, plants will be shipped in spring with limited perennial types (see Glossary). shipping in summer and fall. Grasses can be used as ground covers, specimen plants, in or near water, perennial borders, rock gardens, or natu- Planting ralized areas. Annual grasses and many perennial grasses When: The best time to plant grasses is spring, so they have attractive flowers and seedheads and are suitable for will be established by the time hot summer months arrive. fresh and dried arrangements. Container-grown grasses can be planted during the sum- mer as long as adequate moisture is supplied. Cool-season Selecting and Buying grasses can be planted in early fall, but plenty of mulch Select a grass that is right for your climate. -

Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica Sebifera)

THE WEEDY TRUTH ABOUT BIOFUELS TIM LOW & CAROL BOOTH Invasive Species Council October 2007 Title: The Weedy Truth About Biofuels Authors: Tim Low & Carol Booth Published by the Invasive Species Council, Melbourne October 2007 Updated March 2008 The INVASIVE SPECIES COUNCIL is a non-government organisation that works to protect the Australian environment from invasive pest species. Address: PO Box 166, Fairfield, Vic 3078 Email: [email protected] Website: www.invasives.org.au Further copies of this report can be obtained from the ISC website at www.invasives.org.au Cover photo: Spartina alterniflora, by the US Department of Agriculture CCOONNTTEENNTTSS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 What are biofuels? ................................................................................................................ 2 The Biofuel industry .............................................................................................................. 4 The problems with biofuels ................................................................................................ 6 Social and economic issues ............................................................................................ 6 Greenhouse issues ............................................................................................................ 7 Biodiversity issues ........................................................................................................... -

Chinese Tallow Invasion in Maritime Forests: Understand Invasion Mechanism and Develop Ecologically-Based Management Lauren Susan Pile Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2015 Chinese Tallow Invasion in Maritime Forests: Understand Invasion Mechanism and Develop Ecologically-Based Management Lauren Susan Pile Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pile, Lauren Susan, "Chinese Tallow Invasion in Maritime Forests: Understand Invasion Mechanism and Develop Ecologically-Based Management" (2015). All Dissertations. 1807. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1807 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHINESE TALLOW INVASION IN MARITIME FORESTS: UNDERSTAND INVASION MECHANISM AND DEVELOP ECOLOGICALLY-BASED MANAGEMENT A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Forest Resources by Lauren Susan Pile December 2015 Accepted by: G. Geoff Wang, Committee Chair William C. Bridges Jr. Patricia A. Layton Thomas A. Waldrop Joan L. Walker ABSTRACT Invasion by highly aggressive, non-native, invasive plants is a significant threat to management and conservation priorities as these plants can transform ecosystem functions and processes. In this study, I investigated the non-native, invasive tree, Chinese tallow -

2020 Invasive Species Update

Quiet Invasion: 2020 Invasive Species Update Lisa Gonzalez Invasive Species: The Continuing Problem • New species being reported • Invasive species management is multi‐ faceted and long‐term • Few eradication success stories Policy Research Management Education & & Awareness Restoration What We Know Common Characteristics Impacts • fast seed germination • nutrient cycling • high population growth • local hydrology • early reproductive maturity • fire regimes • reproduction vegetatively as well as sexually • geomorphological processes (such as dune formation or stream profile) • generalized pollination • species and structural diversity • wide tolerance to many habitat types • disease • adaptation to disturbance • impacts available wildlife resources • high rate of biomass accumulation • prevents recruitment of native species due to • long‐range seed dispersal capabilities competition for light, nutrients, and/or moisture • fruit used by wildlife (including humans) • economic losses and costs • relative lack of predators or diseases in • sense of place and quality of life present location Pathways of Introduction • Landscaping and horticulture • Mowing equipment and soils • Shipping materials • Aquarium trade and aquarists • Shipping and boating • Agriculture and livestock • Internet sales • Live seafood markets, bait • Biological control • Scientific research institutions, public aquaria, zoos, arboreta, wildlife preserves Longstanding Invaders • Giant reed Arundo donax • Yellow bluestem Bothriochloa ischaemum • Japanese honeysuckle Lonicera -

Chinese Tallowtree and Carolina Ash Seedlings

Species: Triadica sebifera Page 1 of 30 SPECIES: Triadica sebifera z Introductory z Distribution and occurrence z Botanical and ecological characteristics z Fire ecology z Fire effects z Management considerations z References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Triadica sebifera z AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION z FEIS ABBREVIATION z SYNONYMS z NRCS PLANT CODE z COMMON NAMES z TAXONOMY z LIFE FORM z FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS z OTHER STATUS Jeff Hutchison, Archbold Biological Station AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Meyer, Rachelle. 2005. Triadica sebifera. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [ ]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: TRISEB SYNONYMS: Sapium sebiferum (L.) Roxb. [36,88,132,134] NRCS PLANT CODE [129]: TRSE6 COMMON NAMES: tallowtree Chinese tallow popcorn tree Florida aspen chicken tree http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/triseb/all.html 9/26/2007 Species: Triadica sebifera Page 2 of 30 TAXONOMY: The scientific name of tallowtree is Triadica sebifera (L.) Small (Euphorbiaceae) [30,57,129]. LIFE FORM: Tree FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS: None OTHER STATUS: Tallowtree is considered a noxious weed in Florida. Its sale there was prohibited in 1998 [127]. The Southern Region of the Forest Service has listed it as a Category 1 weed species [128]. It is also included in the top 10 exotic pest plants in Georgia by the Georgia Exotic Pest Plant Council [34] and listed as a "red alert" species in California by the California Invasive Pest Plant Council [9]. DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE SPECIES: Triadica sebifera z GENERAL DISTRIBUTION z ECOSYSTEMS z STATES/PROVINCES z BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS z KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS z SAF COVER TYPES z SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES z HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES Cheryl McCormick, The University of Georgia, IPM Images GENERAL DISTRIBUTION: Tallowtree is a native of China and Japan [29,68,69,76,131,134].