Japanese Approaches to Religion / Spirituality Dr. Harold Netland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Advisement Resources Part Ii

RELIGIOUS ADVISEMENT RESOURCES 2020 PART II Notice Regarding External Resources: The listed resources are provided in this document are operated by other government organizations, commercial firms, educational institutions, and private parties. We have no control over the information of these resources which may contain information that could be objectionable or which may not otherwise conform to Department of Defense policies. These listings are offered as a convenience and for informational purposes only. Their inclusion here does not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the Department of Defense of any of the products, services, or opinions of the external providers. The Department of Defense bears no responsibility for the accuracy or the content of these resources. 1 FAITH AND BELIEF SYSTEMS U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Religious Beliefs and Practices http://www.acfsa.org/documents/dietsReligious/FederalGuidelinesInmateReligiousBeliefsandPractices032702.pdf Buddhism Native American Eastern Rite Catholicism Odinism/Asatru Hinduism Protestant Christianity Islam Rastfari Judaism Roman Catholic Christianity Moorish Science Temple of America Sikh Dharma Nation of Islam Wicca U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Religious Literacy Primer https://crcc.usc.edu/files/2015/02/Primer-HighRes.pdf Baha’i Earth-Based Spirituality Buddhism Hinduism Christianity: Anabaptist Humanism Anglican/Episcopal Islam Christian Science Jainism Evangelical Judaism Jehovah’s Witnesses -

The Japanese Religio-Cultural Context

CHAPTER TWO THE JAPANESE RELIGIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT Introduction This chapter introduces three factors that provide essential background information for my investigation into Endo’s theology of inculturation. First, I give a historical sketch of Japanese religion. Secondly, I look at different types of Shinto and clarify aspects of koshinto that inform contemporary Japanese culture. This is important as koshinto with its modern, psychological, and spiritual meanings is the type of Shinto that I observe in Endo’s attempts at inculturation. In connection with this I introduce the Japanese concept of the ‘divine’, and its role in the history of Shinto-Buddhist-Christian relationships. I also go on to propose that koshinto plays a fundamental role in shaping both different types of womanhood in Japan and the negative theology that forms a background to Endo’s type of inculturation. Outline of Features in Japanese Religious History Japan’s indigenous faith is Shinto, which has its roots in the age prior to 300 B.C. The animistic beliefs of this primal religion developed into a community religion with local shrines for household and guardian gods, where people worshipped the divine spirits. Gradually people began to worship ideal kami, personal kami and ancestorial kami.1 This form of Shinto is frequently called ‘proto-shinto’. Confucianism was introduced to Japan near the beginning of the 5th century as a code of moral precepts rather than a religion.2 Buddhism came to Japan from India 1 The Japanese word kami is usually translated into English by the term deity, deities, spirits, or gods. Kami in Japanese can be singular and/or plural. -

Final Announcement

Final Announcement 1) General Information The Thirteenth International Conference on Ultra-Relativistic Nucleus - Nucleus Collisions will be held on December 1 - 5, 1997 in Tsukuba, Japan. Like previous Quark Matter conferences, the major focus at the conference will be on experimental and theoretical highlights in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, with emphasis on the production and characteristics of high temperature/density and of the quark gluon plasma. The site of the conference will be University Hall complex of the University of Tsukuba and will begin on Sunday evening, November 30, with a welcome reception. The conference will end around noon on December 5. The official language of the conference will be English. This conference is sponsored by the Yamada Science Foundation as the XLVIII Yamada Conference and by the University of Tsukuba. This conference is also supported by the Commemorative Association for the Japan World Exposition (1970), High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK) and The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN). 2) Scientific Program The scientific program will begin at 9:00 A.M. on Monday, December 1, and will end at 12:30 P.M. on Friday, December 5. The conference will consist of nine plenary sessions, two afternoons of parallel sessions and poster sessions. In addition, the exhibitions by companies will be held in Room F (Fourth Conference Room). Please refer to the enclosed preliminary scientific program for details. All the sessions will be held in the building of the University Hall complex. a) Plenary Session: There will be 29 plenary talks and 6 summary talks. As a first trial in this series of conferences, summary talks of the parallel sessions will be presented on Friday morning, where all the highlights of the parallel sessions will be discussed. -

Amami Island Religion - Historical Dynamics of the Islanders’ Spirit - Megumi TAKARABE and Akira NISHIMURA

KAWAI, K., TERADA, R. and KUWAHARA, S. (eds): The Islands of Kagoshima Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands, 15 March 2013 Chapter 3 Amami Island Religion - Historical Dynamics of the Islanders’ Spirit - Megumi TAKARABE and Akira NISHIMURA 1. Introduction into “aman’yu” (Amami period),” “aji’yu” (Lords enerally speaking, Japan’s indigenous Shinto period), “nahan’yu” (Ryukyu kingdom period), Gand exogenous Buddhism represent the ma- “yamaton’yu” (Shimadzu controlling period) and jority religions in Japan. These religions have been “america’yu” (American controlling period). Re- recognized as the spiritual pillars of the Japanese. cords are only available from the Naha period on- When compared with the history of religion in Ja- wards and it was the Ryukyu-dominated Amami Is- pan, “Amami Island religion” can be considered lands that welcomed the first unified regime. There unique for its history as well as for its distant loca- are two theories concerning this period, one that it tion from mainland Japan. This is because the reli- began in 1266 (SAKAGUCHI 1921, NOBORI 1949) and gious culture which has existed in various parts of one that it began in 1440 (Richo Jitsuroku). The the Amami Islands comprise a long-standing spiri- latter theory is currently the prevailing view. Ac- tual pillar of the islanders. In other words, the Ama- cordingly, the Amami Islands in the Naha period mi Islands have enjoyed a religious culture of the are said to have lasted for approximately 170 years Ryukyu legacy rather than that of mainland Japan. from 1440 to 1609. This religious culture informs the spiritual base of During the Naha period and the reign of the the Amami Islands today. -

Shinto, Primal Religion and International Identity

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 1, No. 1 (April 1996) Shinto, primal religion and international identity Michael Pye, Marburg eMail: [email protected] National identity and religious diversity in Japan Questions of social and political identity in Japan have almost always been accompanied by perceptions and decisions about religion. This is true with respect both to internal political issues and to the relations between Japan and the wider world. Most commonly these questions have been linked to the changing roles and fortunes of Shinto, the leading indigenous religion of Japan. Central though Shinto is however, it is important to realize that the overall religious situation is more complex and has been so for many centuries. This paper examines some of these complexities. It argues that recent decades in particular have seen the clear emergence of a more general "primal religion" in Japan, leaving Shinto in the position of being one specific religion among others. On the basis of this analysis some of the options for the Shinto religion in an age of internationalization are considered. The complexity of the relations between religion and identity can be documented ever since the Japanese reception of Chinese culture, which led to the self-definition of Shinto as the indigenous religion of Japan. The relationship is evident in the use of two Chinese characters to form the very word Shinto (shen-dao), which was otherwise known, using Japanese vocabulary, as kannagara no michi (the way in accordance with the kami).1 There are of course some grounds for arguing, apparently straightforwardly, that Shinto is the religion of the Japanese people. -

How Religion and Belief Influenced the Way of the Samurai

Sword and Spirit: Bushido in Practice from the Late Sengoku Era through the Edo Period Joe Lovatt Seminar Paper Presented to the Department of History Western Oregon University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History Spring 2009 Approved Date Approved Date Hst 499: Prof. Max Geier & Prof. Narasingha Sil 2 Sword and Spirit: Bushido in Practice from the late Sengoku era through the Edo period By Joe Lovatt The Samurai possessed a strict code of ethics known as Bushido (the way of the warrior), which allowed them to become some of the greatest warrior the world has ever known. However, there were different embodiments of this system, personifications that two Samurai themselves have documented in two of the most well known books ever written by Samurai; The Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi and Hagakure, by Yamamoto Tsunetomo. Bushido has usually been considered an ethical code that was set to a certain standard, just as the ten commandments are. This analysis suggests that it was in fact not a set of moral laws, but that bushido was embodied differently by every Samurai. Bushido was ultimately a guideline, just like rules in religion. It was a path that one was to adhere to as well as they could, but history has made it clear that it depended upon the circumstances in which a Samurai lived; the life of a Samurai in the twelfth century would filled with fighting for their master and practical use of the code; far different from that of a Samurai living during the first half of the 1800’s, who would be keeping track of the business operations of their master instead of fighting. -

The Making of an American Shinto Community

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN SHINTO COMMUNITY By SARAH SPAID ISHIDA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2007 Sarah Spaid Ishida 2 To my brother, Travis 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people assisted in the production of this project. I would like to express my thanks to the many wonderful professors who I have learned from both at Wittenberg University and at the University of Florida, specifically the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Mario Poceski and Dr. Jason Neelis. For their time, advice and assistance, I would like to thank Dr. Travis Smith, Dr. Manuel Vásquez, Eleanor Finnegan, and Phillip Green. I would also like to thank Annie Newman for her continued help and efforts, David Hickey who assisted me in my research, and Paul Gomes III of the University of Hawai’i for volunteering his research to me. Additionally I want to thank all of my friends at the University of Florida and my husband, Kyohei, for their companionship, understanding, and late-night counseling. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend a sincere thanks to the Shinto community of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America and Reverend Koichi Barrish. Without them, this would not have been possible. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................7 -

Creating Modern Japanese Subjects: Morning Rituals from Norito to News and Weather

religions Article Creating Modern Japanese Subjects: Morning Rituals from Norito to News and Weather Wilburn Hansen Department of Religious Studies, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, CA 92182-6062, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Lawrence W. Snyder Received: 8 November 2015; Accepted: 4 February 2016; Published: 11 March 2016 Abstract: This original research on Restoration Shinto Norito seeks to explain the rhetorical devices used in the composition of a morning prayer ritual text. The nativist scholar, Hirata Atsutane, crafted this ritual to create a Japanese imperial subject with a particular understanding of native identity and national unity, appropriate to the context of a Japan in the shadow of impending modernity and fear of Western domination. The conclusions drawn concerning Hirata’s rhetoric are meant to inform our understanding of the technique and power of the contemporary Japanese morning television viewing ritual used to create post-modern Japanese citizens with an identity and unity appropriate to a global secular context. Keywords: Hirata Atsutane; Restoration Shinto; religious ritual; Norito; modernity; identity construction; NHK 1. Introduction This article is an attempt to explicate modern Japanese identity by examining in detail a Shinto morning Norito, a prayer ritual that originated in the 19th century just a few decades before the vaunted modernization and Westernization that occurred after American ships forced the opening of Japan in 1854. Morning prayer rituals are still conducted today by practitioners of the several forms of Japanese Buddhism, Shinto, and New Religions; of course, the complexity and level of focus and dedication depend upon the individual practitioner, as well as the demands of the tradition being practiced. -

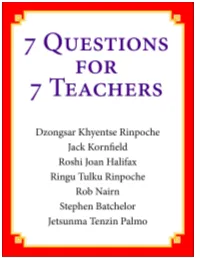

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

Shintō and Buddhism: the Japanese Homogeneous Blend

SHINTŌ AND BUDDHISM: THE JAPANESE HOMOGENEOUS BLEND BIB 590 Guided Research Project Stephen Oliver Canter Dr. Clayton Lindstam Adam Christmas Course Instructors A course paper presented to the Master of Ministry Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Ministry Trinity Baptist College February 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Stephen O. Canter All rights reserved Now therefore fear the LORD, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which your fathers served −Joshua TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... vii Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Chapter One: The History of Japanese Religion..................................................................3 The History of Shintō...............................................................................................5 The Mythical Background of Shintō The Early History of Shintō The History of Buddhism.......................................................................................21 The Founder −− Siddhartha Gautama Buddhism in China Buddhism in Korea and Japan The History of the Blending ..................................................................................32 The Sects That Were Founded after the Blend ......................................................36 Pre-War History (WWII) .......................................................................................39 -

Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal DOI 10.1007/s12280-008-9042-9 Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主 Benjamin A. Elman Received: 12 May 2008 /Accepted: 12 May 2008 # National Science Council, Taiwan 2008 Abstract This article first reviews the political, economic, and cultural context within which Japanese during the Tokugawa era (1600–1866) mastered Kanbun 漢 文 as their elite lingua franca. Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges were based on prestigious classical Chinese texts imported from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) China via the controlled Ningbo-Nagasaki trade and Kanbun texts sent in the other direction, from Japan back to China. The role of Japanese Kanbun teachers in presenting language textbooks for instruction and the larger Japanese adaptation of Chinese studies in the eighteenth century is then contextualized within a new, socio-cultural framework to understand the local, regional, and urban role of the Confucian teacher–scholar in a rapidly changing Tokugawa society. The concluding part of the article is based on new research using rare Kanbun medical materials in the Fujikawa Bunko 富士川文庫 at Kyoto University, which show how some increasingly iconoclastic Japanese scholar–physicians (known as the Goiha 古醫派) appropriated the late Ming and early Qing revival of interest in ancient This article is dedicated to Nathan Sivin for his contributions to the History of Science and Medicine in China. Unfortunately, I was unable to present it at the Johns Hopkins University sessions in July 2008 honoring Professor Sivin or include it in the forthcoming Asia Major festschrift in his honor. -

About Religion in Japan

CK_5_TH_HG_P104_230.QXD 2/14/06 2:23 PM Page 225 The samurai developed a code of ethics known as Bushido, the way of the warrior. According to Bushido, samurai were to be frugal, incorruptible, brave, Teaching Idea self-sacrificing, loyal to their lords, and above all, courageous. It was considered Research groups that have codes of better to commit ritual suicide than to live in dishonor. In time, Zen Buddhism ethics, and compare Bushido to these influenced the samurai code, and self-discipline and self-restraint became two other codes. Restate the “code of important virtues for samurai to master. 45 ethics” for the class, and possibly develop a code of ethics for the class Japan Closed to Outsiders during this unit of study. From 1603 to 1867, the Tokugawa Shogunate ruled Japan. Early in the dynasty, the shogun closed off Japan from most of the rest of the world and reasserted feudal control, which had been loosening. In the 1500s, the first Teaching Idea European traders and missionaries had visited the island nation and brought with Teach students about samurai by them new ideas. Fearing that further contact would weaken their hold on the gov- reading fictional samurai stories. See ernment and the people, the Tokugawa banned virtually all foreigners. One Dutch More Resources for suggestions. ship was allowed to land at Nagasaki once a year to trade. The ban was not limited to Europeans. Only a few Chinese a year were allowed to enter Japan for trading purposes. In addition, the Japanese themselves were not allowed to travel abroad for any reason.