PIGEON RACING and WORKING-CLASS CULTURE in BRITAIN, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Standard Squab Book

fk^i^T-.v^s^p>^::Ss 'pm^'k^y^'-^ •• SqUABBQDK ELMER C RIC ^m fork At ffinrntU TUniverait^ iCibrarg Cornell University Library SF 467.R49 1907 The national standard squab book, 3 1924 000 124 754 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis bool< is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924000124754 The National Standard Squab Book ' ~r ELMER C. RICE. The National Standard Squab Book By Elmer C. Rice A PRACTICAL MANUAL GIVING COMPLETE AND PRECISE DIREC- TIONS FOR THE INSTALLATION AND MANAGEMENT OF A SUC- CESSFUL SQUAB PLANT. FACTS FROM EXPERIENCES OF MANY HOW TO MAKE A PIGEON AND SQUAB BUSINESS PAY, DETAILS OF BUILDING, BUYING, HABITS OF BIRDS, MATING, WATERING, FEEDING, KILLING, COOL- "' ING, MARKETING, SHIPPING, CURING ^ y. ^""^ ^ AILMENTS, AND OTHER INFORMATION ' Illustrated with New Sketches and Half Tone Plates from Photographs Specially Made for this Work BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 1907 Copyright' ISOl, by Elmer C. Bice Copyright, i902, by Elmer C. Rice Copyright, 1903, by Kmer C. Rice Copyright, 1904, by Elmer C. Rice Copyright, 1905, by Elmer C. Rice Copjrright, 1906, by Elmer C. Rice Copyright, 1907, by Elmer C. Rice rights reserved. A WELL-BUILT NEST. Ptees of Murray and Emey Company Boston, Maaa. ILLUSTRATIONS. Page Portrait of the Author {Frontispiece) A Weil-Built Nest 8. Thoroughbreds ....... 14 How a Back Yard may be Fixed for Pigeons 18 Cheap but Practical Nest Boxes 22 How City Dwellers without Land may Breed Squabs 24 Unit Squab House (with Passageway) and Flying Pen 26 Nest Boxes Built of Lumber . -

Management of Racing Pigeons

37_Racing Pigeons.qxd 8/24/2005 9:46 AM Page 849 CHAPTER 37 Management of Racing Pigeons JAN HOOIMEIJER, DVM Open flock management, which is used in racing pigeon medicine, assumes the individual pigeon is less impor- tant than the flock as a whole, even if that individual is monetarily very valuable. The goal when dealing with rac- ing pigeons is to create an overall healthy flock com- posed of viable individuals. This maximizes performance and profit. Under ideal circumstances, problems are pre- vented and infectious diseases are controlled. In contrast, poultry and (parrot) aviculture medicine is based on the principles of the closed flock concept. With this concept, prevention of disease relies on testing, vaccinating and a strict quarantine protocol — measures that are not inte- gral to racing pigeon management. This difference is due to the very nature of the sport of pigeon racing; contact among different pigeon lofts (pigeon houses) constantly occurs. Every week during the racing season, pigeons travel — confined with thou- sands of other pigeons in special trucks — to the release site. Pigeons from different lofts are put together in bas- kets. Confused pigeons frequently enter a strange loft. In addition, training birds may come into contact with wild birds during daily flight sessions. Thus, there is no way to prevent exposure to contagious diseases within the pop- ulation or to maintain a closed flock. The pigeon fancier also must be aware that once a disease is symptomatic, the contagious peak has often already occurred, so pre- ventive treatment is too late. Treatment at this point may be limited to minimizing morbidity and mortality. -

Wonder Bag Depth 16" Handle 18" No

AVIARY WEST fiird Neb No. AW-36 Diameter 11" Bag Depth 16" Handle 36" No. AW-18 Diameter 11" Wonder Bag Depth 16" Handle 18" No. AW-12 8" Win~8 ~~~mDe:;~h 11" i Handle 12" ~ by Weldell Phillips Call or write us~If' Playa del Rey, California forinformati;n.priCin~g.~...~~~~~~iir Our nets feature 100% ~~~if/.r:n,tlJ nylon netting, hardwood handles, and spring steel hoops. 3018 LA PLATA AVENUE HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745 Since the beginning of time, man's de In World War I homing pigeons were (213) 330-8700 sire to control his own destiny has been used when other forms of communication responsible for many ingenious methods were impossible to establish. The 77th of long distance communication. Division, famed 'Lost Battallion of Tireless marathon runners, throbbing Argonne,' was saved from total de drums and intricate smoke signals indicate struction by Cher Ami, last of the sticken :/A the age-old desperate human desire for group's seven homers. The doomed men rapidly received news. The Pharaohs of were being unintentionally pounded to Sunshine Egypt relied on the swiftest of dependable pieces by their own artillery. In despera creatures, the homing pigeon, whose abil tion, Cher Ami was released into the i'ish and Rtr ity to unerringly fly hundreds of miles to metal-strewn sky. Although grieviously their homes, helped them build a highly wounded in flight, the valiant bird finally eompany cultured civilization. fluttered down to the roof of his home loft SPECIALIZING IN The earliest record of homing pigeons, at Rampont. -

Belgian Winners We Make the Difference

TESTED AND APPROVED BY SUCCESSFUL PIGEON FANCIERS. 2021 - ENG ® OROVET WINNERS With Belgian Winners we make the difference. Thomas Lataire CEO Group Lataire bv Belgian Winners stands for Belgian top quality. The success with pigeons depends on a combina 1 n the product ion department of Orovet bv, a tion of factors: the experience of the fancier, the subsidiary of Groupe Lataire bv, high quality quality of the pigeons, the loft and the nutritional health products for racing pigeons are produced support. With the nutritional system of Belgian and developed. Winners, we make the difference. Precisely because the quality, the type of raw material and its application makes the differen ce, we have surrounded ourselves with a nutriti on expert from the sports world, a pigeon vet, a nutrition engineer and an experience expert. The "pigeon sport" evolves just as in all other sports. The "type" athlete and his guidance from the past, wouldn't even carne to work today. Why? Because in all branches of sport, the bar is being raised more and more. Every pigeon fancier has his own opinion and in terpretation concerning the use of supplements. But it's a good thing too. Ambachtenlaan 3-5 9880 Aalter Belgium group History in animal feed sales since 1947 Lata1re animal healthcare The Lataire family is ready for the third generati on as a trader in ani mal feed. 1 n 194 7 Gerard Lataire started a company in grains and feed in Beernem (Belgium) and served the farmers in the region with the brands Remy (Wijgmaal), Vanhove (Ledeberg), Buysse (1 ngelmunster), Talpe (Kortrijk) and Debaillie (Roeselare). -

NPA Constitution

Constitution of the National Pigeon Association, Inc. Note: This is the Constitutional document as amended by decision of the membership in January, 2015 ARTICLE C I: NAME The name of the organization shall be the NATIONAL PIGEON ASSOCIATION, INC. ARTICLE C II: PURPOSE Section 1: The purpose of this organization shall be to foster and create greater interest in the breeding and improvement of all recognized breeds and varieties of domestic pigeons. Section 2: To better acquaint individuals with the adaptability of pigeon raising. Correct the false impression that domestic pigeons carry communicable diseases and educate the public regarding the pleasure and profits derived from pigeon keeping. Section 3: To sponsor annually the NPA Grand National, Regional, District and State pigeon shows, for the purpose of bringing together master displays of all breeds and varieties of standard-bred pigeons, where they may compete with one another for coveted honors and enable all concerned to observe the progress made in the science of breeding. Section 4: To compile, publish and distribute educational literature on the various branches of the pigeon industry that may assist others in acquiring practical knowledge that will enable them to raise pigeons successfully. Section 5: To issue seamless individually identifiable leg bands for all breeds and varieties of pigeons. These bands shall bear the initials NPA and the year in which they are issued. Section 6: To ratify, maintain and provide all standards by which pigeons are judged at the Grand National and other pigeon shows held under NPA rules, where ribbons, money or other awards are offered. -

Since I Was 13 Years Old I Have Had Pigeons. First, for a Short Period Dutch High Flyers, Owls and Such, and Even a Racing Pigeon That Wandered In

Since I was 13 years old I have had pigeons. First, for a short period Dutch High Flyers, Owls and such, and even a racing pigeon that wandered in. On the advice of my father, who, up to that time had nothing to do with pigeons, I began to focus on racing pigeons and in 1960 I participated for the first time as a junior member in my first Race. At home nobody kept birds, my father had tropical fish and my grandfather had a pair of canaries. From my 6th year I have had birds, starting with a canary and a few tropical birds. From 1960 to 2000 I had pigeons without any break despite the fact that I've moved several times in that period for my work. Below: The lofts and outside aviaries from Roel Bijkerk in the backyard in Winschoten. At my current address in Winschoten I specialized in the so-called "over-night races", ie races between 900 and 1250 km. My greatest achievement was winning the first prize in a national competition from Ruffec (France 903 km) to the North of the Netherlands. In 2000, I had a heart attack and ended up in the hospital. After that time my pleasure in the pigeon racing sport declined, not so much by the heart attack, but more for reasons of a poor understanding between the pigeon fanciers, also things like drugs, doping and more and more expensive technical progress (?), digital time clocks etc. which more or less obliged people to invest a great deal of money, so the hobby was no longer financially viable for a for an increasing number of people. -

Managing Bird Strike Risk Species Information Sheets

MANAGING BIRD STRIKE RISK SPECIES INFORMATION SHEETS AIRPORT PRACTICE NOTE 6 1 SILVER GULL 2 2 MASKED LAPWING 7 3 DUCK 12 4 RAPTORS 16 5 IBIS 22 6 GALAH 28 7 AUSTRALIAN MAGPIE 33 8 FERAL PIGEON 37 9 FLYING-FOX 42 10 BLACK KITE 47 11 PELICAN 50 12 MARTIN AND SWALLOW 54 13 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 58 Legislative Protection Given to Each Species 58 Land Use Planning Near Airports 59 Bird Management at Off-airport Sites 61 Managing Birds at Landfills 62 Reducing the Water Attraction 63 Grass Management 64 Reporting Wildlife Strikes 65 Using Pyrotechnics 66 Knowing When and How to Lethal Control 67 Types of Dispersal Tools 68 What is Separation-based Management 69 How to Use Data 70 Health and Safety: Handling Biological Remains 71 Getting Species Identification Right 72 Defining a Wildlife Strike 73 CONTENTS PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 2015 ii MANAGING BIRD STRIKE RISK SPECIES INFORMATION SHEETS INTRODUCTION The Australian Airports Association (AAA) commissioned These new and revised fact sheets provide airport preparation of this Airport Practice Note to provide members with useful information and data regarding 1 SILVER GULL 2 aerodrome operators with species information fact common wildlife species around Australian aerodromes sheets to assist them to manage the wildlife hazards and how best to manage these animals. The up-to-date 2 MASKED LAPWING 7 at their aerodrome. The species information fact sheets suite of species information fact sheets will provide were originally published in June 2004 by the Australian aerodrome operators with access to data, information 3 DUCK 12 Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) as Bird Information and management techniques for the species posing Fact Sheets. -

Fancy Mice, Their Varieties and Management As Pets Or for Show, Including the Latest Scientific Information As to Breeding for C

.S o p^ ^-» ^ o0) C/5 g •H o E - o TO C o •H (ii Q OJ OS 'Lf\ r-i fc VN XjA C\J CTn CO _3 S O (-1 2yC:J.Davies -\V ONE & ALL SEEDS, 5 FANCY MICE. Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 924001 01 3246 : FANCY MICE Their Varieties and Management as Pets or for Show. Including the latest Scientific Information as to Breeding for Colour. Fifth Edition, Completely Revised, By C. J. DAVIES. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, Bazaar Buildings, Drury Lane, W.C. 1912. Books for Fanciers. Each Is. net, by post Is. 2d. The Management of Rabbits. Third edition, revised and enlarged by Meredith ^^ Fradd. DOMESTrC AND FANCY CATS; including the Points of Show Varieties, Preparing for Exhibition and Treatment for ; the Diseases and Parasites. By John Jennings. English and Welsh Terriers. Their Uses, Points, and Show Preparation. By J Maxtee. Scotch and Irish Terriers. With chapters on the Housing, Training, and minor Diseases of Terriers in general. A companion handbook to the above. Diseases of Dogs, a very practical handbook which every Dog-Owner should have at hand. Fourth edition, revised by A. C. PiESSE, M.R.C.V.S. Pet Monkeys, a complete and excellent book by Arthur H. Patterson, A.M.B.A. Second edition. Pigeon-Keeping for Amateurs. Describing practically all varieties of Pigeons. By James C. -

A Current Review of Avian Influenza in Pigeons and Doves (Columbidae)

A current review of avian influenza in pigeons and doves (Columbidae) Celia Abolnik * Department of Production Animal Studies, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X04, Onderstepoort, Pretoria 0110, South Africa G Model VETMIC-6544; No. of Pages 16 2 C. Abolnik / Veterinary Microbiology xxx (2014) xxx–xxx 8. Regulatory concerns . 000 8.1. Artificial insemination as a route of AIV transmission in pigeons and doves . 000 8.2. Vertical transmission of AIV in pigeons and doves. 000 9. Conclusions . 000 Acknowledgements . 000 References . 000 1. Introduction between poultry sites during disease outbreaks. The latest global concern is a poultry-origin LPAI H7N9 strain, Avian influenza is a serious disease of poultry and some recently detected in healthy pigeons. As of 1 December mammals caused by certain serotypes of the influenza A 2013, this strain has already caused 139 laboratory- virus (AIV), a member of the family Orthomyxoviridae. confirmed human cases with 47 fatalities in China (Li et al., Ducks and shorebirds are the global natural hosts in which 2014). AIVs usually cause sub-clinical infections (Alexander, Feral pigeons and doves naturally associate with 2000). Serotypes are classified by the combination of environments where food, water and nesting sites are two major antigens on the virion, namely hemagglutinin available, leading to close association with humans and (H) and neuraminidase (N). Until recently, 16 H-types and poultry in cities and on farms. Pigeon racing is a popular nine N-types were acknowledged, but a 17th and 18th H- and growing sport, increasingly so in East Asia, and a type plus a 10th and 11th-N type were recently discovered multi-million dollar industry. -

Pigeon Husbandry

PIGEON HUSBANDRY INTRODUCTION Please note that this information is intended primarily for members of the genera Columba (includes common pigeon or rock dove and all breeds thereof), Streptopelia (ring- necked and related doves), and Geopelia (diamond and related doves). General Information The bird order Columbiformes contains as many as 316 species in 10 families and subfamilies. There are some species that are currently threatened or endangered and some species have become extinct during the past few centuries (including the dodo bird). Although Columbids share distinct physical features with each other there is still quite a bit of diversity within this group Pet pigeons nest building and sitting on fake eggs. Photo credit: Elizabeth Young. of birds. Some Columbids are tropical forest dwellers subsisting on insects and fruit for a large part of the diet whereas our more familiar species are primarily granivorous (eating seeds and Diet grains). Some species are more similar to pheasants than to our Our most common species of pigeons and doves should be fed a classic idea of a pigeon (e.g., the common pigeon or rock dove). seed and grain mix appropriate for the size of the bird. This can Common pigeons (domestic pigeons) usually lay 2 plain white eggs be supplemented with formulated pigeon pellets or small parrot and incubate them for about 18 days. They are prolific breeders pellets. Because Columbids swallow their food whole, they rely on and can nest year-round if food is available. The nest is a loose powerful gizzard contractions to grind their food. There is debate collection of straw or sticks on a ledge or, for some species, on a about whether grit in the gizzard is needed to help grind the food. -

Who Is the Fastest Racing Pigeon of All? a Preliminary Study on the Influence of the Physical Condition of Racing Pigeons on Their Flight Performance in A

Who is the fastest racing pigeon of all? A preliminary study on the influence of the physical condition of racing pigeons on their flight performance in a varying environment. Lizanne Jeninga 14-2-2018 Wageningen University & Research Nederlandse Postduivenhouders Resource ecology group Organisatie Who is the fastest racing pigeon of all? A preliminary study on the influence of the physical condition of racing pigeons on their flight performance in a varying environment. Author Lizanne Jeninga (student number: 930520-399-120) In the context of my master thesis, part of the study Forest and Nature Conservation. Supervisors Fred de Boer & Kevin Matson Wageningen University & Research Resource Ecology Group Droevendaalsesteeg 3a, 6708 PB Wageningen Contact person NPO Leo van der Waart Wageningen, 14 February 2018 Preface and acknowledgements Various studies have addressed the navigational abilities of pigeons during their flight and how they form habitual routes. However, in contrast, few is known about the factors influencing the flight performance of a pigeon during a race; for instance, is the habitual route influenceable? This research report is the result of a study that is performed in context of a master thesis at the Wageningen University and Research in cooperation with the Dutch Racing Pigeon Fanciers Organisation (NPO) and deals with the effects of the physiological traits of pigeons on the flight performance and how this is related to the environmental circumstances they encounter along the route to home. The field study and this research report are established by the help of a lot of people. I want to thank everyone who has contributed. -

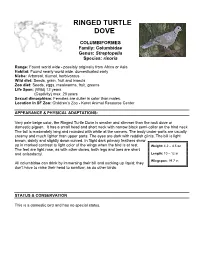

Ringed Turtle Dove

RINGED TURTLE DOVE COLUMBIFORMES Family: Columbidae Genus: Streptopelia Species: risoria Range: Found world wide - possibly originally from Africa or Asia Habitat: Found nearly world wide, domesticated early. Niche: Arboreal, diurnal, herbivorous Wild diet: Seeds, grain, fruit and insects Zoo diet: Seeds, eggs, mealworms, fruit, greens Life Span: (Wild) 12 years (Captivity) max. 20 years Sexual dimorphism: Females are duller in color than males. Location in SF Zoo: Children’s Zoo - Koret Animal Resource Center APPEARANCE & PHYSICAL ADAPTATIONS: Very pale beige color, the Ringed Turtle Dove is smaller and slimmer than the rock dove or domestic pigeon. It has a small head and short neck with narrow black semi-collar on the hind neck. The tail is moderately long and rounded with white at the comers. The body under-parts are usually creamy and much lighter than upper parts. The eyes are dark with reddish glints. The bill is light brown, dainty and slightly down curved. In flight dark primary feathers show up in marked contrast to light color of the wings when the bird is at rest. Weight: 4.2 – 4.5 oz The feet are light rose, as with other doves, both legs and toes are short and anisodactyl. Length: 10 – 12 in Wingspan: 19.7 in All columbidae can drink by immersing their bill and sucking up liquid; they don't have to raise their head to swallow, as do other birds. STATUS & CONSERVATION This is a domestic bird and has no special status. COMMUNICATION AND OTHER BEHAVIOR Low cooing voice. Not so mournful as that of the mourning Dove.