Star-Cross'd Lovers: Shakespeare and Prokofiev's 'Pas-De-Deux' In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce

m ill iiiii;!: t!;:!iiii; PS Al V-ID BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henrg W, Sage 1891 B^^WiS _ i.i|j(i5 Cornell University Library PS 1097.A1 1909 V.10 The collected works of Ambrose Blerce. 3 1924 021 998 889 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021998889 THE COLLECTED WORKS OF AMBROSE BIERCE VOLUME X UIBI f\^^°\\\i COPYHIGHT, 1911, Br THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY CONTENTS PAGE THE OPINIONATOR The Novel 17 On Literary Criticism 25 Stage Illusion 49 The Matter of Manner 57 On Reading New Books 65 Alphab£tes and Border Ruffians .... 69 To Train a Writer 75 As to Cartooning 79 The S. p. W 87 Portraits of Elderly Authors .... 95 Wit and Humor 98 Word Changes and Slang . ... 103 The Ravages of Shakspearitis .... 109 England's Laureate 113 Hall Caine on Hall Gaining . • "7 Visions of the Night . .... 132 THE REVIEWER Edwin Markham's Poems 137 "The Kreutzer Sonata" .... 149 Emma Frances Dawson 166 Marie Bashkirtseff 172 A Poet and His Poem 177 THE CONTROVERSIALIST An Insurrection of the Peasantry . 189 CONTENTS page Montagues and Capulets 209 A Dead Lion . 212 The Short Story 234 Who are Great? 249 Poetry and Verse 256 Thought and Feeling 274 THE' TIMOROUS REPORTER The Passing of Satire 2S1 Some Disadvantages of Genius 285 Our Sacrosanct Orthography . 299 The Author as an Opportunity 306 On Posthumous Renown . -

Romeo and Juliet 2019-20 Study Guide

Romeo and Juliet 2019-20 Study Guide ABOUT THIS STUDY GUIDE The Colorado Shakespeare Festival will send actors to your school soon as part of a Shakespeare & Violence Prevention project. This study guide is a resource for you, whether you are an administra- tor, counselor, teacher, or student. Our program is most successful when schools have prepared in advance, so we encourage you to use this study guide to connect the material to your curriculum. Shakespeare offers a wonderful opportunity to explore meaningful questions, and we encourage you and your students to engage deeply with those questions. Study guide written and edited by Dr. Amanda Giguere, Dr. Heidi Schmidt, and Isabel Smith-Bernstein. ABOUT SHAKESPEARE & VIOLENCE PREVENTION The Colorado Shakespeare Festival partners with CU Boulder’s Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence (CSPV) and the Department of Theatre & Dance to create a touring program that in- creases awareness of Shakespeare and violence prevention. Our actors will visit your school to perform an abridged three-actor version of Romeo and Juliet that explores the cycle of violence, using research from the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence. In this 45-minute performance, we draw parallels between Shakespeare’s world and our own. We recommend the performance for grades 6-12. Theatre is about teamwork, empathy, and change. When your students watch the play, they will observe mistreatment, cruelty, violence, and reconciliation. They’ll see examples of unhealthy and destructive relationships, as well as characters who become “upstanders”—people who make the choice to help. This play is intended to open up the dialogue about the cycle of violence and mis- treatment—and to remind us all that change is always possible. -

Romeo and Juliet I

15 Romeo And Juliet I Romeo And Juliet is one of the most famous love stories of all time. It takes Verona place in the city of Verona, Italy. Where is Verona? Verona is a rich and beautiful city in Italy. Map of Italy Copy A Family Feud In Romeo And Juliet, there are two wealthy families, the Capulets and the Montagues. The Capulets and the Montagues are not on good terms. If you are a Capulet, it is your duty to dislike Montagues. If you are a Montague, you will be a disgrace to your family if you are friends with a Capulet. Imagine meeting the person you dislike most! Sampson and Gregory work for the Capulets, while Abraham and Balthasar work for the Montagues. How do you think the men feel when they bump into each other on the streets of Verona? Well, Sampson decides to insult the Montagues. An insult is something rude that people do or say to others. In those days, it was very rude to bite your thumb at someone, and that is whatEvaluation Sampson did when he saw Abraham and Balthasar! 83 Romeo And Juliet I A Quarrel Read the following script aloud. Then act out the story. Characters Sampson Abraham (from the house of Capulet) (from the house of Capulet) Balthasar Gregory (from the house of Montague) (from the house of Montague) Benvolio (a Montague) Tybalt (a Capulet) Other members of the Citizens two families Setting Copy Verona SAMPSON I will bite my thumb at them. That’s a great insult! ABRAHAM (noticing SAMPSON) Do you bite your thumb at us, sir? SAMPSON I do bite my thumb, sir. -

Romeo & Juliet

Romeo and Juliet The Atlanta Shakespeare Company Staff Artistic Director Jeff Watkins Director of Education and Training Laura Cole Development Director Rivka Levin Education Staff Kati Grace Brown, Tony Brown, Andrew Houchins, Adam King, Amanda Lindsey, Samantha Smith Box Office Manager Becky Cormier Finch Art Manager Amee Vyas Marketing Manager Jeanette Meierhofer Company Manager Joe Rossidivito Unless otherwise noted, photos appearing in this study guide are courtesy of Jeff Watkins. Study guide by Samantha Smith The Atlanta Shakespeare Company 499 Peachtree St NE Atlanta GA 30308 404-874-5299 www.shakespearetavern.com Like the Atlanta Shakespeare Company on Facebook and follow ASC on Twitter at @shakespearetav. DIRECTOR'S NOTE ONe of the thiNgs I love most about Shakespeare is that his stories prejudices are too deep aNd too violeNt to be overcome carry differeNt meaNiNgs for me at differeNt poiNts iN my life. by youNg love; iNstead it takes the deaths of two What resoNates for me about the story of Romeo aNd Juliet right iNtelligeNt, kiNd, empathetic youNg people to make the Now is the impact aNd terrible cost of prejudice aNd hatred for the feudiNg Capulets aNd MoNtagues fiNally call each other people iN the play. The Capulets aNd MoNtagues are Not writteN "brother." Right Now, that's the part of this story that's as villaiNs. They are ordiNary people who go about their busiNess moviNg me the most: the warNiNg call to examiNe our aNd care for their owN. But they have beeN raised to hate each owN grudges aNd prejudices aNd thiNk about the other aNd are set iN their ways; they stubborNly adhere to their coNsequeNces of those prejudices for ourselves aNd geNeratioNs-old family feud, refusiNg to let their old grudges go others. -

Romeo & Juliet

ROMEO & JULIET Student’s Book A play and film study guide Educasia Education in Context Before You Start… 1. You are about to read and watch the story of Romeo and Juliet. Look at the two pictures below, and try to answer the following questions: Who are Romeo and Juliet? What is their relationship? How will their relationship change throughout the story? How will the film and play be different? 2. Read the following introduction to the play, and answer the questions. This is the most famous of all Shakespeare’s plays, first printed in 1597. Romeo and Juliet meet, fall in love, and promise to be faithful to each other forever. Love is strong, but not as strong as family tradition, or hate, or revenge. Like young people all over the world, Romeo and Juliet want the right to decide their future for themselves, but in the end, their families are too powerful for them. Romeo and Juliet cannot live without each other, and if they are not allowed to marry and live together, there is only one way out. According to the introduction, are the following sentences true (T), false (F) or doesn’t it say (DS)? a. Romeo and Juliet have been lovers since they were children. b. Romeo and Juliet’s families are enemies. c. Romeo and Juliet are married. d. Their families eventually allow them to be together. 1 Characters in the Play The Montague family Lord Montague Lady Montague Romeo, the Montagues’ son Nurse, from Benvolio, Romeo’s cousin the 1968 film The Capulet family Lord Capulet Lady Capulet Juliet, the Capulets’ daughter Romeo and Juliet, Tybalt, Juliet’s cousin from the 1916 film. -

Romantic and Realistic Impulses in the Dramas of August Strindberg

Romantic and realistic impulses in the dramas of August Strindberg Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Dinken, Barney Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 13:12:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557865 ROMANTIC AND REALISTIC IMPULSES IN THE DRAMAS OF AUGUST STRINDBERG by Barney Michael Dinken A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF DRAMA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 1 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fu lfillm e n t of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available,to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests fo r permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship, In a ll other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Shakespeare and the Friars

38 DOMINICAN A to obtain pea.ce for Europe, could prayers, saluting Mary with a She refuse to hear the voice of single heart and with a single the whole Catholic world on its voice, imploring Mary, placing knees? Let us be as one, with all hope in Mary!'' It is with the Holy Father of the faithful this unanimous prayer that Cath in prayer, Mary's own prayer, and olics will obtain the return to strive to sprea.d it. "How ad Christ of the nations that are mirable it will be to see in the astray, the salvation of the world cities, in the towns, and in the and that peace so eagerly desired. villages, on hnd and on sea, as far Mary, the Dove of Peace, offers as the Catholic name extends, the Olive Branch-Her Rosary. hundreds of thousands of the Will the world accept it? faithful, uniting their praises and Aquinas McDonnell, 0. P. SHAKESPEARE AND THE FRIARS. "The thousand souled Shake is his portrayal of it. His name speare" is an epitath bestowed is em blazoned far aboye all other on the master writer of the most English writers. He is praised momentous epoch in the history and lauded by all nations and of the literary world. Thousand why? Because no one equals souled is Shakespeare. No one him in creative power of mind, is more deserving of such a title. in vividness of imagination, in His genius is bounded by no richness of imagery. No one country. He is of no age. He equals him in his comprehFmsion is uni-r ersal. -

A Pair of Star Crossed Lovers Take Their Life…” Is a Passage from the Prologue

Name: Multiple Choice Act I _____ 1. “A pair of star crossed lovers take their life…” is a passage from the prologue. The term “star- crossed levers” means: a. Romeo and Juliet are destined by fate not to have a happy life b. Romeo compared Juliet’s eyes to stars c. Romeo and Juliet used the stars to find each other d. Their getting together was predicted by the stars _____ 2. Benvolio tries to make peace during the street brawl but is stopped by: a. the Prince b. Tybalt c. someone biting his thumb at him d. Romeo _____ 3. At the beginning of the play, Romeo is sad because: a. Tybalt vowed to kill him b. Rosalyn will not return his love c. Juliet will not return his love d. because of the big fight _____ 4. At the party, a. Tybalt recognizes Romeo b. Lord Capulet tells Tybalt to kill Romeo c. Mercutio gets drunk b. Benvolio falls in love with Juliet Act II _____ 5. Juliet professes her love for Romeo because: a. she is mad at her father b. she is scared that since he is a Montague, he will hate her c. she is unaware that he is in the garden listening d. Romeo tells her he loves her first _____ 6. “Wherefore art thou Romeo?” means: a. Why are you Romeo? b. Who is Romeo? c. Where are you Romeo? d. Yo! What sup? _____ 7. That night they agree to: a. keep their love a secret b. get married c. kill Tybalt d. -

Romeo and Juliet | Program Notes

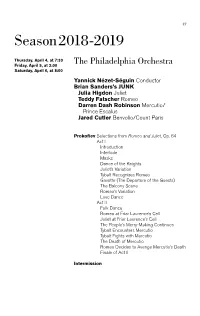

27 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, April 4, at 7:30 Friday, April 5, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, April 6, at 8:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Brian Sanders’s JUNK Julia Higdon Juliet Teddy Fatscher Romeo Darren Dash Robinson Mercutio/ Prince Escalus Jared Cutler Benvolio/Count Paris ProkofievSelections from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64 Act I Introduction Interlude Masks Dance of the Knights Juliet’s Variation Tybalt Recognizes Romeo Gavotte (The Departure of the Guests) The Balcony Scene Romeo’s Variation Love Dance Act II Folk Dance Romeo at Friar Laurence’s Cell Juliet at Friar Laurence’s Cell The People’s Merry-Making Continues Tybalt Encounters Mercutio Tybalt Fights with Mercutio The Death of Mercutio Romeo Decides to Avenge Mercutio’s Death Finale of Act II Intermission 28 Act III Introduction Farewell Before Parting Juliet Refuses to Marry Paris Juliet Alone Interlude At Friar Laurence’s Cell Interlude Juliet Alone Dance of the Girls with Lilies At Juliet’s Bedside Act IV Juliet’s Funeral The Death of Juliet Additional cast: Aaron Mitchell Frank Leone Kyle Yackoski Kelly Trevlyn Amelia Estrada Briannon Holstein Jess Adams This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. These concerts are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. These concerts are made possible, in part, through income from the Allison Vulgamore Legacy Endowment Fund. The April 4 concert is sponsored by Sandra and David Marshall. The April 5 concert is sponsored by Gail Ehrlich in memory of Dr. George E. -

West Side Story As Shakespearean Tragedy and a Celebration of Love and Forgiveness

“The Boy Must Die? Yes, the Boy Must Die”: West Side Story as Shakespearean Tragedy and a Celebration of Love and Forgiveness West Side Story is based on Shakespeare’s tragedy, Romeo and Juliet, and is considered to be one of the finest adaptations of a Shakespearean play ever written. The structure of the first act of West Side Story follows almost exactly the structure of the first three acts of Romeo and Juliet. And the major characters of West Side Story, Tony and Maria, are parallels to Romeo and Juliet. The opening fight between the Jets and the Sharks mirrors the fight between the Montagues and Capulets and this fight is broken up by the modern American representation of the law, Officer Krupke, instead of the Prince who weighs in against the two warring clans in Renaissance Verona. In both the modern musical and the Renaissance tragedy, the opening scene, in the manner of Greek tragedy, lays bare the plague that afflicts society—unchecked violence exacerbated by extreme prejudice. The two scenes that follow, the introduction of Romeo/Tony, and of Juliet/Maria, depict the longing of the young to escape from this plague. Romeo/Tony knows that the current trajectory of his life is meaningless and hopes that a new path will open up for him. And Juliet/Maria does not want to marry within the narrow confines of her familial/ethnic group, seeking instead to forge her own path for her own life. Thus the conflict between the protagonists and an antagonistic society is established. When Romeo/Tony and Juliet/Maria meet and fall in love in the next two scenes, the dance and balcony scenes, this conflict is set in motion. -

Mambo from Symphonic Dances from West Side Story

SECONDARY 10 PIECES PLUS! MAMBO from WEST SIDE STORY by LEONARD BERNSTEIN TEACHER PAGES MAMBO FROM WEST SIDE STORY by LEONARD BERNSTEIN http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3scL8v6zh11NbPqRdTZYW00/mambo-from-symphonic-dances- from-west-side-story CONTEXT The Mambo is a dance which originated in Cuba and means a ‘conversation with the Gods’. It can be traced back to the 18th Century and the influence of English, Spanish, French and African country dances. This dance music was subsequently developed and modified by musicians from Puerto Rico, becoming very lively and rhythmical. The musical characteristics of the style are riffs in the brass and woodwind sections and very percussive, rhythmical accompaniment punctuated by vocal shouts. The underlying 2:3 or 3:2 ‘son clave’ patterns links with the Cuban Salsa - hot and spicy! The dance became really popular and when recordings of the music arrived in America in the 1950’s, a real Mambo craze erupted in New York. When Leonard Bernstein decided to write West Side Story, the musical based on Romeo and Juliet, he chose New York for the setting at a time when the popularity of the Mambo was at its height. In the story the two rival gangs, the ‘Jets’ and ‘Sharks’ (Montagues and Capulets) meet at a school dance, organised to encourage the social integration of the two ethnic groups. The circle dance gradually changes into a wild, aggressive and provocative mambo – an escalating competition between rival dancers as they flaunt increasingly extravagant steps. It is during this dance that Tony and Maria (Romeo and Juliet) first set eyes on each other. -

Shakespeare Newsletter

Do you have five minutes, even three? That’s all you need to read one article in this newsletter. If you like it, there’s more, read on. If ways that Bill still matters not, well you get the idea what we’re up to here. an occasional newsletter, Fall 2012 Incorporating Friends into Shakespeare By Blair Warner Shakespeare. The greatest playwright ever, whom many fear, including myself. But I am here to tell you that Bill is not so bad. Reading Shakespeare is less dif- ficult if you think of the plays as people you know. Not the plays, of course, but the characters in the plays. Just envision people that you know as you read the scenes—pretend they are the ones on stage. It might sound silly, but it really helped me while reading Taming of the Shrew. I imagined one of my close friends Ashley playing the role of Bianca and her younger sister Nicole playing the role of Katherina. Both sisters have personalities that can be compared to the two sisters in the play. Ashley, who is soft-spoken at times, is very nice and peaceful, like Bianca. She gets along with everyone that she meets. Nicole is much more like Katherina. She is strong-willed, says whatever happens to be on her mind, and at times can be angry. People tend to be intimidated by her mannerisms. Just like Kate in Taming. Imagining the similarities between these pairs of sisters as I read made me laugh at times, enjoying Taming more and more as I read.