Media and Communication Open Access Journal | ISSN: 2183-2439

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Publishing Instructors

Our Publishing Instructors Our instructors are respected industry experts. They all work in publishing and bring up-to- date, applied knowledge to every course. Elizabeth d’Anjou is a freelance editor with over 25 years of experience serving a diverse clientele, including educational publishers, corporations, government, and non-profit agencies. She is a sought-after speaker and trainer, offering workshops on a number of editing-related topics across the country through Editors Canada and in corporate settings. She has twice served on the Editors Canada national executive, most recently as Director of Standards, and has co-chaired local branches in Toronto and Kingston. Current and past clients include Nelson Education, the RCMP, the Osgoode Hall Law Journal, and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Course(s): CDPB 102, CDPB 312 Saffron Beckwith is President at Ampersand Inc. As part of Canada’s longest-serving commissioned sales force, she has experience selling everything from Harry Potter to first-time poets. She has been teaching since 2004 and loves teaching and selling. Course(s): CDPB 105 Gary Bennett is a publishing professional with over 25 years’ experience. Currently VP Digital Studio at Pearson Education in Toronto, he manages a diverse team of developers and producers who support Pearson Canada's domestic digital and print publishing programs for both K-12 and Higher Education. He has prior experience as a Publisher, Acquisitions Editor, Marketing Manager, Sales Representative, and Sales Manager. Previously, he has worked at John Wiley & Sons, McGraw-Hill Ryerson, and Nelson Canada. Course(s): CDPB 101 Camilla Blakeley is a partner in Blakeley Words+Pictures. -

Annual Report 2003 Annual Report 2003 Bertelsmann Bertelsmann Financial Highlights in € Millions

Bertelsmann Annual Report 2003 Annual Report2003 Bertelsmann Financial Highlights in € millions IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS Pro forma 7/1/2001 2000/ 2003 2002 2001 –12/31/2001 2001 Business Development Revenues 16,801 18,312 18,979 9,685 16,748 Operating EBITA 1,123 936 573 164 826 Net income before minority interests 208 968 1,378 931 987 Cash Flow 1,373 1,115 294 127 160 Investments 761 5,263 2,639 1,067 2,744 Total assets 20,164 22,188 23,734 23,734 17,245 Personnel costs 4,151 4,554 4,812 2,343 4,319 Employees (in absolute numbers) Germany 27,064 31,712 31,870 31,870 30,732 Other countries 46,157 48,920 48,426 48,426 43,816 Total 73,221 80,632 80,296 80,296 74,548 Equity Subscribed capital 1) 606 606 606 606 463 Retained earnings 6,060 6,079 5,697 5,697 3,222 Minority interests 965 1,059 2,081 2,081 792 Equity 7,631 7,744 8,384 8,384 4,477 As percentage of total assets 38 35 35 35 26 Net financial debt 820 2,741 859 859 2,298 Debt payback factor 2) 0.6 2.5 2.9 n/m n/m Net Income Net income before minority interests 208 968 1,378 931 987 Minority interests 54 40 (143) (18) 246 Dividend 220 240 n/a 300 50 Profit participation payments 3) 76 77 77 39 95 Employee profit sharing 3) 29 34 n/a 19 44 1) 57.6 percent Bertelsmann Foundation, 17.3 percent Mohn family, 25.1 percent Groupe Bruxelles Lambert (GBL) (as of 12/31/2003) 2) Net financial debt/Cash Flow 3) Offset in net income Bertelsmann Annual Report 2003 Contents | 1 Letter from the Chairman 2 Executive Board 6 Management Report 10 Supervisory Board Report 48 Corporate Governance at Bertelsmann 50 Contents Annual Report January 1 through December 31, 2003 Consolidated Financial Statements as of December 31, 2003 Consolidated Income Statement 54 Consolidated Balance Sheet 55 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 56 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity 57 Segment Reporting 58 Notes 60 Boards/Mandates 104 Auditor’s Report 107 Select Terms at a Glance 108 2 | Letter from the Chairman Bertelsmann Annual Report 2003 Dear Friends of Bertelsmann, Berlin is a fascinating city. -

PDF Article Download

London Book Fair Briefcase 2015 Opiiniion - LBF Tuesday, 7th April 2015 BookBrunch asked literary agents for their hot titles for the 2015 London Book Fair. Aiitken Allexander Sara Baume's SPILL SIMMER FALTER WITHER (published in Ireland by Tramp Press) is a story about a man, a dog, and loneliness (Wm Heinemann UK). ADDLANDS by Tom Bullllough is about two generations of a farming family as modernity encroaches (Granta UK; Random House US). Cllare Cllark's new novel is WE THAT ARE LEFT, which explores the devastating after-effects on a family of the First World War (Harvill Secker UK; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt US; Flammarion France; Hoffman & Campe Germany). A LITTLE LIFE by Hanya Yanagiihara traces the fortunes of four school friends over three decades in New York as they move from adolescence to grapple with money, addiction, sex and success (Picador UK; Doubleday US). POSTCAPITALISM by Channel 4 Economics Editor Paull Mason argues that from the ashes of the financial crisis, we have the chance to create a more socially just and sustainable economy (Allen Lane UK; Farrar, Straus US). Andrew Wiillson's ALEXANDER MCQUEEN: BLOOD BENEATH THE SKIN is "modern fairy tale infused with the darkness of Greek Tragedy", telling the story of McQueen's battle to gain entry to the world of fashion and his rise to its heights before it destroyed him (Simon & Schuster UK; Scribner US; rights sold in Poland and China; film rights sold). Darlley Anderson Associiates In THE CURIOUS CHARMS OF ARTHUR PEPPER by Phaedra Patriick (left), 69-year-old Arthur's discovery of a mysterious charm bracelet in his late wife's possessions sends him on an epic quest to find out the truth about her secret life before they met (Mira UK; Mira US; Rocco Brazil; Btb Germany; Garzanti Italy; Luitingh- Sijthof the Netherlands; Forum Sweden). -

Thomas B. Costain

Thomas B. Costain: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Costain, Thomas Bertram, 1885-1965 Title: Thomas B. Costain Collection Dates: 1885-1966 Extent: 12 document boxes, 12 record center cartons (16.2 linear feet), 17 galley folders (gf), 2 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: Thomas Bertram Costain was a Canadian journalist and writer of historical novels. His collection mainly consists of correspondence and miscellaneous items, including memoranda, notes, and correspondence between publishing companies and literary agents. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-0940 Language: English Access: Open for research. Part or all of this collection is housed off-site and may require up to three business days' notice for access in the Ransom Center's Reading and Viewing Room. Please contact the Center before requesting this material: [email protected]. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gifts, 1962-1995 (R1304, R2347, R5374, G10283) Processed by: Heather Bollinger, 2012 Note: This finding aid replicates some information previously available only in a card catalog. Please see the explanatory note at the end of this finding aid for information regarding the arrangement of the manuscripts as well as the abbreviations commonly used in descriptions. Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Costain, Thomas Bertram, 1885-1965 Manuscript Collection MS-0940 2 Costain, Thomas Bertram, 1885-1965 Manuscript Collection MS-0940 3 Costain, Thomas Bertram, 1885-1965 Manuscript Collection MS-0940 Works: Container [Untitled article re Sinclair Lewis], Tccms (5pp), 1954 March 31. 1.1 [Untitled lecture re The Canadian Club of New York], Tms/draft/inc with A revisions [4pp], Tccms with A emendations (5pp), nd. -

Elementary Catalog 2020 Inspire Teachers and Learners with Outstanding Books

Elementary Catalog 2020 Inspire Teachers and Learners with Outstanding Books BOARD BOOKS LEVELED READERS SOCIO-EMOTIONAL LEARNING INCLUSIVE TEXTS STEAM NONFICTION FICTION AWARD WINNERS Dear Educators, When a catalog that lists books arrives in my mailbox, I stop everything and browse excitedly through the pages! I can’t resist the pull of learning about books that I can order for my students. The catalog you’re holding now, filled with page after page of outstanding books, from the Penguin Random House family of publishers was developed especially to support you and the children you teach! If you’re like me, you’ll want to choose books for your class library and guided reading groups that focus on students’ interests. Remember to reserve time to include your students in the book selection process. Take a few minutes and ask them to turn-and-talk to a partner about books they’d love to see in their classroom. Then, have students jot on a piece of notebook paper the topics they’re curious about, authors they love, series they want to read, and favorite genres. Adding books students suggest to your classroom collections honors them as readers and shows how much you value and respect their input. The more books your students read and enjoy, the more they’ll improve. Volume and choice in reading matters! Happy reading! Laura Robb EDUCATOR, AUTHOR, AND LITERACY SPECIALIST A classroom teacher for more than 43 years, Laura is the author of more than thirty books on Literacy and the new “Let’s Work Together Teaching Guide” series from Penguin Random House Education. -

Vintage Michael Joseph Transworld

VINTAGE MICHAEL JOSEPH PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE TRANSLATION RIGHTS GUIDE TRANSWORLD London Book Fair 2020 Translation Rights Michael Joseph specialises in women’s fiction, crime, thrillers, cookery, memoirs and lifestyle books. Many of its authors are now, or soon will be, household names in the UK and around the world. GENERAL FICTION Michael Joseph specialises in women’s fiction, publishing established brands like Marian Keyes, Jojo Moyes, Liane Moriarty, Conn Iggulden and Fredrik Backman as well as signing and launching debut novelists. Other authors include Dawn French, Sylvia Day, Giovanna Fletcher, Stephen Fry and Lesley Pearse. CRIME FICTION Michael Joseph publishes crime fiction by authors at home on the bestseller lists, whether they’re up-and- coming or established in the genre, including M.J. Arlidge, Tim Weaver, Tom Clancy and Clive Cussler. NON-FICTION MEMOIR Either the secrets behind the success of the already famous, or a story that no-one has heard before, the authors writing memoirs include Sue Perkins, Tom Jones, Stephen Fry, Jeremy Clarkson, Michael McIntyre, and Steven Gerrard. COOKERY Whether it is the country’s bestselling cookery writer – Jamie Oliver – or a debut from the brightest and freshest young chefs, Michael Joseph’s list covers everything from gourmet baking to healthy eating, to catering for events or how to eat well on a budget. As well as Jamie Oliver, authors include Rachel Khoo, Nadiya Hussain and Chrissy Teigen. NON-FICTION LIFESTYLE Health and wellbeing is a core specialist area for Michael Joseph, and from exercise and style advice to mindfulness and well-being, its range of publishing is extensive. -

Annual Report 2004

ANNUAL REPORT 2004 RTL GROUP RANDOM HOUSE GRUNER + JAHR BMG ARVATO DIRECT GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2004 REPORT ANNUAL BERTELSMANN Bertelsmann Financial Highlights in € millions IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS Pro forma 7/1/–12/31/ 2004 2003 2002 2001 2001 Business Development Revenues 17,016 16,801 18,312 18,979 9,685 Operating EBIT 1,429–––– Operating EBITA – 1,123 936 573 164 Net income before minority interest 1,217 208 968 1,378 931 Investments 930 761 5,263 2,639 1,067 Total assets 20,970 20,164 22,188 23,734 23,734 Personnel costs 4,204 4,151 4,554 4,812 2,343 Equity Subscribed capital 1,000 606 606 606 606 Retained earnings 6,510 6,060 6,079 5,697 5,697 Minority interest 1,336 965 1,059 2,081 2,081 Equity 8,846 7,631 7,744 8,384 8,384 As percentage of total assets 42 38 35 35 35 Economic debt1) 2,632–––– Leverage factor2) 1.6–––– Net financial debt – 820 2,741 859 859 Debt payback factor3) – 0.6 2.5 2.9 – Net income Net income before minority interest 1,217 208 968 1,378 931 Net income after minority interest 1,032 154 928 1,235 949 Dividend Bertelsmann AG 324 220 240 – 300 Employees (in absolute numbers) Germany 27,350 27,064 31,712 31,870 31,870 Other countries 48,916 46,157 48,920 48,426 48,426 Total 76,266 73,221 80,632 80,296 80,296 Profit participation payments 76 76 77 77 39 Employee profit sharing 29 29 34 – 19 1) Net financial debt plus provisions for pensions and profit participation capital 2) Economic debt / Operating EBITDA (after modifications) 3) Net financial debt / Cash Flow Bertelsmann Annual Report 2004 Contents | 1 ANNUAL -

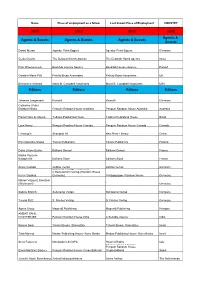

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

PJ's Bookcase - All Pricing Is in Canadian Dollars

PJ's Bookcase - All pricing is in Canadian dollars. Shipping NOT included. Click on the Order page on our website to place your order and fill out the form. 1 Qty Inv. No. ISBN Author Title Publisher Category Type Cond. Additional Notes Sale Price 1 B2015-0002 978-1-4000-6617-9 Alda, Alan Things I Overheard While Talking to Myself Random House 200 Biography H E Autographed $15.00 Amos, Tori and Ann 1 B2016-0035A 0-7679-1676-X Tori Amos, Piece by Piece Broadway Books, NY, 2005 Biography H E $11.95 Powers 1 B2015-0006 0-445-04028-9 Andrews, Bart Story of I Love Lucy, The Popular Library 1977 Biography S G $2.00 1 B2015-0249 0-553-37972-0 Angelou, Maya Even the Stars Look Lonesome Bantam Books, N.Y. 1998 Biography ST VG $6.00 1 B2015-0005 0-553-38009-5 Angelou, Maya Heart of a Woman, The Bantam Books 1997 Biography ST VG $6.00 1 B2015-0185 0-553-38009-5 Angelou, Maya Heart of a Woman, The Bantam Books, 1997 Biography ST VG $6.00 1 B2015-0007 978-0-312-38104-2 Anka, Paul My Way - An Autobiography St. Martin's Press, 2013 Biography H E $12.00 1 B2015-0008 1-894662-36-5 Arden, Jann If I Knew, Don't You Think I'd Tell Ya? Insomniac Press 2002 Biography ST E $7.00 1 B2015-0009 978-0-670-06536-3 Baksi, Kurdo Stieg Larsson, My Friend Viking Canada 2010 Biography H E $8.50 1 B2015-0192 978-0-425-17731-0 Ball, Lucille Love, Lucy Berlkey Boulevard Books, 1997 Biography S E $4.00 1 B2015-0220 978-0-7710-7600-2 Barker, Edna (Editor) Remembering Peter Gzowki, A Book of Tributes McClelland & Stewart, 2002 Biography H E $7.00 The Windmill Press, Surrey, UK, 1 B2015-0273 No ISBN Barrymaine, Norman The Story of Peter Townsend Biography H G 2nd Printing $9.00 1958 PJ's Bookcase - All pricing is in Canadian dollars. -

1 Introduction 2 Contextualizing the Issues

Notes 1 Introduction 1. In 2013, the group changed the name of the event to ‘The March to End Rape Culture’ (SlutWalk Philadelphia 2013). However, the SlutWalk Philadelphia Facebook page is still extremely active and is used to promote this march. 2. Unfortunately, just days before the walk was scheduled to take place, SlutWalk Seattle had to cancel their event after their sound specialist vol- unteer pulled out at the last minute and they could not find someone to replace them. As organiser Laura Delgado explained, ‘it seemed impractical to keep trotting on right up to the deadline without that element planned out’ (Delgado 2014b). 3. Websites and Facebook groups consulted include: SlutWalk Aotearoa, SlutWalk Bangalore, SlutWalk Chicago, SlutWalk India, SlutWalk Johannesburg, SlutWalk London, SlutWalk Perth, SlutWalk Seattle, SlutWalk Singapore, SlutWalk Toronto, SlutWalk Winnipeg. 2 Contextualizing the Issues 1. In fact, there is even talk about a Fourth Wave of activists, who are defined by their use of new media technologies to create a new feminist movement online (see Cochrane 2013). However, although the term Fourth Wave has been coined, it has yet to be a label embraced by feminist scholars or feminists themselves (Keller 2013). 2. Surprisingly, although Reclaim the Night marches have been staged since the late 1970s, I found no academic research exploring its representations in the news media. 3. Heather Jarvis (2012) told me that the first secret organising group she heard of started out of Atlanta, but that there are several in operation, many of which are in languages other than English. She also added that certain groups have closed down over the years due to disagreements which she sees as ‘natural’, given most organisers are survivors of sexual assault and are dealing with a lot of pain and healing. -

Canada's Largest Recreational Reading Program White Pine Award™ Winners and Nominees 2002–2021

An Ontario Library Association Initiative Canada’s largest White Pine Award™ recreational Winners and Nominees reading program 2002–2021 Official Wholesaler 1 2021 Break in Case of Emergency ★ Hunted by the Sky ★ Brian Francis Tanaz Bhathena HarperCollins Canada Penguin Teen Canada Charming As A Verb Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me Ben Philippe Mariko Tamaki & Rosemary Valero-O’Connell HarperCollins US Groundwood Books Fan the Fame Like a Love Story Anna Priemaza Abdi Nazemian HarperTeen (HarperCollins US) HarperCollins US Frying Plantain The Starlight Claim Zalika Reid-Benta Tim Wynne-Jones House of Anansi Press Candlewick Press He Must Like You You Don’t Have To Die in the End Danielle Young-Ullman Anita Daher Penguin Teen Canada Yellow Dog 2 2020 All Our Broken Pieces The Field Guide to the North American L.D. Crichton Teenager Disney Hyperion Ben Philippe Balzer + Bray Baggage Wendy Phillips The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali Coteau Books Sabina Khan Scholastic Canada Ltd The Beauty of the Moment Tanaz Bhathena ★ Sadie ★ Penguin Teen Courtney Summers St. Martin’s Press Comics Will Break Your Heart Faith Erin Hicks Synchro Boy Roaring Brook Press Shannon McFerran Arsenal Pulp Press Crown of Feathers Nicki Pau Preto We Contain Multitudes Simon Pulse Sarah Henstra Penguin Teen 2019 36 Questions That Changed A Girl Like That My Mind About You Tanaz Bhathena Vicki Grant Farrar Straus Giroux Running Press Teens The Mosaic ★ The Agony of Bun O’Keefe ★ Nina Berkhout Heather T. Smith Groundwood Books Penguin Teen Canada Munro vs. The Coyote Black Chuck Darren Groth Regan McDonell Orca Book Publishers Orca Book Publishers Prince of Pot Catching the Light Tanya Lloyd Kyi Susan Sinnott Groundwood Books Vagrant Press Recipe for Hate Chaotic Good Warren Kinsella Whitney Gardner Dundurn Press A. -

Frankfurt 2017 Judy Klein

…………………… FRANKFURT 2017 Rights Guide Counterpoint Catapult Black Balloon Soft Skull …… iUniverse Star Feral House Outpost19 Featherproof Lifestyle Entrepreneurs Press …… Dana Newman Literary Agency Sandra Bond Literary Agency …………………… JUDY KLEIN [email protected] 01.917.414.1578 ELIZABETH ROSNER SURVIVOR CAFÉ The Legacy of Trauma and the Labyrinth of Memory COUNTERPOINT | NON-FICTION | SEPTEMBER 2017 Sold: AUDIO/Novel Audio “A rare blend of scholarly assessment and personal revelation… important and vital…with an elegance and eloquence that reverberates with both depth and nuance.” —Booklist, Starred “Combines moving personal narrative with illuminating research…Each page is imbued with urgency, with sincerity, with heartache, with heart."—San Francisco Chronicle “A thoughtful, probing meditation on the fragility of memory and the indelible inheritance of pain." —Kirkus "Rosner shines an unblinking light on the most horrific of 20th-century crimes and asks, what is the intergenerational legacy of trauma? … Rosner’s conclusions: that powerful suffering must be communicated before healing can occur and that the most profound of human atrocities must be acknowledged so that their like does not happen again."—Publishers Weekly "A beautifully expressed personal examination of how trauma is passed down through generations...An exquisite read."—The Daily Gazette “A breathtaking overview of events as varied as the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, the Rwandan genocide, and Japanese American internment….Survivor Café takes on important issues