RHODE ISLAND M Edical J Ournal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHODE ISLAND M Edical J Ournal

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL FEEDING OVERVIEW OF HYPERBARIC CHILDREN IN MEDICINE CENTER AT KENT HONDURAS PAGE 13 PAGE 19 BUTLER CREATES ARONSON CHAIR PAGE 44 GOOGLE GLASS MAGAZINER: IN RIH ED FIXING HEALTH CARE PAGE 47 PAGE 45 APRIL 2014 VOLUME 97• NUMBER 4 ISSN 2327-2228 Some things have changed in 25 years. Some things have not. Since 1988, physicians have trusted us to understand their professional liability, property, and personal insurance needs. Working with multiple insurers allows us to offer you choice and the convenience of one-stop shopping. Call us. 800-559-6711 rims I B C RIMS-INSURANCE BROKERAGE CORPORATION Medical/Professional Liability Property/Casualty Life/Health/Disability RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 7 COMMENTARY An Up-Front Guide to Getting Promoted: Slow and Steady JOSEPH H. FRIEDMAN, MD By the Sweat of Your Brow STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 41 RIMS NEWS CME: Eleventh Hour Education Event RIMS at the AMA National Advocacy Conference Why You Should Join RIMS 54 SPOTLIGHT Jordan Sack, MD’14: His early struggles with deafness and those who inspired him to help others 61 Physician’s LEXICON The Manifold Directions of Medicine STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 63 HERITAGE Timeless Advice to Doctors: You Must Relax MARY KORR RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL IN THE NEWS BUTLER HOSPITAL 44 51 JAMES F. PADBURY, MD creates Aronson Chair for receives March of Dimes Neurodegenerative research grant Disorders 52 BRENNA ANDERSON, MD IRA MAGAZINER 45 studies Group A strep on how to fix health care in pregnancy LIFESPAN 47 creates Clinical 52 SAMUEL C. -

Kent Hospital, a Member of Care New England | Rhode Island

BECOMING AN AGE-FRIENDLY HEALTH SYSTEM MEMBERS IN ACTION CASE STUDY Kent Hospital, a member of Care New England | Rhode Island Overview by CNE, South County Health and the Rhode Island Primary Care Physicians Corporation, a multispecialty In February 2019, Kent Hospital, part of Care New independent practice association. England, opened an Adult Care for Elders (ACE) unit to CNE realized to do true population health, it needed to test and implement the Age-Friendly Health Systems meet the needs of its older adults, particularly at Kent 4Ms Framework. The unit focused on documenting Hospital in Warwick, R.I., where the patient volume what matters to the patient and implementing delirium is highest. Since 2014, the health system and Kent screening and prevention plan on all patients. Since leadership teams have supported the growth of a opening, the unit has service line in geriatrics seen a reduction in both and clinical programs length of stay and falls to serve the needs of with injury, along with an older adults across the increase in patient and continuum of care. staff satisfaction. At the start of CNE’s The mission of Care New work to build a service England (CNE) is to be line in geriatric medicine, “your partner in health” a needs assessment and create a community was performed at Kent of healthier people in the Hospital. Admission areas served by the health statistics demonstrated system’s hospitals and that more than 30% of hospital admissions were partners. The 749-bed health system includes five patients over the age of 65, and of that group, most hospitals, a medical group, and a wellness center. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 616 JC 000 555 TITLE Career Placement and Graduate TransferReport, 1999. INSTITUTION Community Coll. of Rhode Island, Warwick. PUB DATE 2000-06-00 NOTE 62p.; Cover title varies. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Transfer Students; CommunityColleges; Education Work Relationship; Graduate Surveys;Higher Education; *Job Placement; *Outcomes of Education;*Student Employment; *Transfer Rates (College) IDENTIFIERS *Community College of Rhode Island ABSTRACT The document presents thesurvey results on the employment and continuing status of the 1999 graduates of the Community College ofRhode Island (CCRI). The statisticalbreakdown reveals that 80.4 percent of the 1999 graduates are employed (48.7percent full-time), 33.4 percentare continuing their education (11.9percent full-time), and 4.8 percent continue to seek employment. Data aboutemployment status, educational aspirations, and average salaries are providedfor graduates in 27 fields. Of the 196 Business Administration graduateswho responded, 108 (55.1%) indicatedthat they were employed full time. BusinessAdministration graduates had an average annual salary of $29,420 ($14,352-$62,400range). Among graduates of the Criminal Justice and LegalStudies Program who responded, 82 (61.7%) indicated full-time employment. Theprogram meets the requirements established by many police departments,which mandate successful completion of 60 hours of college course work in law enforcement for considerationfor employment. The Liberal Arts degreeprogram is designed for students intending to transfer to baccalaureatedegree programs following graduation from CCRI. Graduates transfer mostoften to Rhode Island College andthe University of Rhode Island. Of the251 graduates of the program who responded, 56 (22.3%) indicated"education full-time," 61 (24.3%) indicated "education full-time/employed part-time,"and 71 (28.3%) indicated "employed full-time." Appendices are included. -

Philanthropy Officer, Kent Hospital Care New England Providence, RI

Philanthropy Officer, Kent Hospital Care New England Providence, RI www.carenewengland.org Care New England Health System (CNE) – a trusted regional healthcare organization providing comprehensive, world-class clinical care, advancing medical research, and attracting the nation’s top specialty-trained physicians – seeks a seasoned fundraiser to lead the strategic development and management of a major gifts program for Kent Hospital in Warwick, Rhode Island. This is an exciting career opportunity to advance the mission of a beloved hospital committed to being a partner with the community in improving the health of its people. Rhode Island’s second largest hospital serving approximately 300,000 area residents, Kent’s offerings include a 359-bed acute care hospital, an Ambulatory Surgery Center, a Women’s Diagnostic Imaging Center, a Wound Recovery Center, and laboratory and primary care services at various sites throughout the community. Last year, Kent and the Spaulding Rehabilitation Network launched the Spaulding Outpatient Center at Kent Hospital with locations in Providence, East Greenwich, and Pawtucket. A teaching affiliate of Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School and The University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine, Kent’s clinical services include cancer care, cardiovascular care in collaboration with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, OBGYN, primary care, infectious disease, orthopedics/sports medicine, and surgical services (including bariatric surgery). Its high-performing Emergency Department is the second largest in RI with 70,000 visits annually. Position Summary: Reporting to CNE’s Chief Philanthropy Officer and working closely with Kent Hospital’s President and senior leadership team, the Philanthropy Officer will develop Kent’s grateful patient fundraising program with an emphasis on donor pipeline building in support of current and future programs, services, and campaigns. -

Kent Hospital

2016 Community Health Needs Assessment Table of Contents Our Commitment to Community Health 2 2016 CHNA Overview: A Statewide Approach to Community Health 4 Improvement 2016 CHNA Partners Research Methodology Leadership Research Partner Alignment with Public Health Community Engagement Prioritization of Community Health Needs Development of a Community Health Improvement Plan Board Approval and Adoption Kent Hospital Service Area 7 Kent Hospital Service Area Demographics 8 Statistical Health Data for the Kent Hospital Service Area 11 Kent Hospital Utilization Data Analysis 36 West Warwick Partner Forum 43 Evaluation of Community Health Impact from 2013 CHNA Implementation Plan 48 Kent Hospital Implementation Plan for Community Health Improvement 52 Board Approval and Adoption 58 Appendices Appendix A: Our Partners 59 Appendix B: Statistical Health Data References 60 Kent Hospital 2016 Final CHNA Report Page 1 Our Commitment to Community Health Kent Hospital, the second largest hospital in Rhode Island, provides a full spectrum of primary and acute care services including: weight loss surgery program; emergency department with rapid assessment and virtually no wait; the Breast Health Center at Kent, a collaboration with Women & Infants Hospital; cardiology services, The Inpatient Rehabilitation Center at Kent, the state’s only 24-hour emergency hyperbaric oxygen facility; the Stroke Center; and an ambulatory surgery center. Kent Hospital is an affiliate of the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine (UNECOM) for medical education. Care New England Health System, the not-for-profit parent organization, founded in 1996, is a trusted organization that fuels the latest advances in medical research, attracts the nation’s top specialty-trained doctors, hones renowned services and innovative programs, and engages in the important discussions people need to have about their health and end-of-life wishes. -

Appointments

PEOPLE / PLACES Appointments Dr. C. James Sung appointed to leadership roles Heather A. Smith, MD, MPH, in Pathology And Laboratory Medicine at Women reappointed to AMA & Infants, Care New England, Brown legislative Council C. JAMES SUNG, MD, FCAP, has The American Medical Association been appointed chief of pathology Board reappointed HEATHER A. and laboratory medicine at Wom- SMITH, MD, MPH, a member of en & Infants Hospital of Rhode Is- the AMA Foundation Board, to the land, executive chief of pathology Council on Legislation (COL). Her and laboratory medicine at Care new one-year term begins July 1. New England, and vice chair of pa- An obstetrician/gynecologist affil- thology and laboratory medicine at iated with Women and Infants Hospital, she is a graduate of The Warren Alpert Medical School the University of Virginia and the Boston University School of of Brown University. Dr. Sung has Public Health. served as interim chief since 2017. Dr. Smith earned her medical degree at the University of “Dr. Sung has been an integral member of the leadership team Massachusetts Medical School and a certificate of health sci- of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine for 20 ences research at Yale University. She completed a residency in years. For the past two years, he has led the entire department obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital – in an interim role, further stabilizing its operations, and mod- Massachusetts General Hospital and is a graduate of the Robert ernizing and consolidating laboratory service across Care New Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program at Yale. -

Facts Figures& the DIVISION of BIOLOGY and MEDICINE by the Numbers

BROWN UNIVERSITY 2020 Facts Figures& THE DIVISION OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE By the Numbers On campus, in the affiliated hospitals, and in our community, our faculty, students, and staff are hard at work, unified in their mission to create new knowledge, to teach and to learn, and to change the world through research. These figures tell the story of the growth and development happening at Brown. JACK A. ELIAS, MD SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT FOR HEALTH AFFAIRS DEAN OF MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES FRANK L. DAY PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY DIVISION OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE biology faculty. 150 medical academic faculty . .599 medical clinical faculty. 1,737 BASIC SCIENCE DEPARTMENTS • Ecology and Evolutionary Biology • Molecular Biology, Cell Biology, and Biochemistry • Molecular Microbiology and Immunology • Molecular Pharmacology, Physiology, and Biotechnology • Neuroscience MEDICAL DEPARTMENTS • Anesthesiology • Dermatology • Diagnostic Imaging photo: Lauryn Ashford MD’22 with a patient. • Emergency Medicine • Family Medicine • Medicine • Neurology • Neurosurgery The Warren Alpert Medical School • Obstetrics and Gynecology became the first in the country whose • Orthopaedics • Pediatrics graduates will all have the training required • Psychiatry and Human Behavior to prescribe medications to treat opioid use • Radiation Oncology disorder in any US state. The training is • Surgery provided over all four years of medical school HYBRID and has been approved by the Substance Abuse • Medical Science and Mental Health Services Administration. • Pathology and Laboratory Medicine PROGRAM IN BIOLOGY Degrees Awarded in 2019 Sohini Ramachandran, PhD, undergraduate. 185 received the 2019 Presidential PhDs awarded . .34 Early Career Award in Science and master’s degrees awarded . .63 Engineering, the nation’s highest award for scientists and engineers Graduate Education in the early stages of their research postdoctoral research associates careers. -

2004-Fall.Pdf

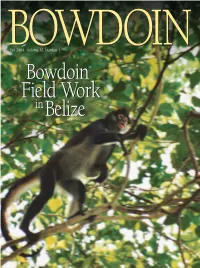

• General Books • Bowdoin Authors • Chamberlain Titles • T-shirts • Sweatshirts • Shorts • Pants • Outerwear • Hats • Children’s Clothing • Women’s Wear • Insignia Gifts Wear Clothing • Women’s Outerwear • Hats Children’s BOWDOINBOWDOINFall 2004 Volume 76, Number 1 OnlineOnline www.bowdoin.edu/bookstorewww.bowdoin.edu/bookstore BowdoinBowdoin FieldField WorkWork ininBelizeBelize shop online anytime or call toll free at 1-800-524-2225 Monday-Friday, 8:30 a.m.-5:00 p.m. EST Paperweights • Blankets Throws Clocks Mirrors Bowdoin Chair • Diploma Frames • Glassware • Pennants • Banners • Gift Certificates • Decals • and much more • Non-Profit U.S.Postage BOWDOIN PAID Bowdoin Bowdoin College College Brunswick, Maine 04011 fall2004 contents BOWDOINeditor’s note staff Knowing how to do things is becoming a lost art. The four children in my own Volume 76, Number 1 household — who range in age from 11 to 15 — worry about this from time to Fall, 2004 What Makes Laffey Run? 12 time, especially the boys. One of them said recently that he feels that his genera- MAGAZINE STAFF By Edgar Allen Beem Photographs by Mark Alcarez tion will be helpless when it is their turn to run things. He said it genuinely wor- ried him and that, although it helped a little to know that we could teach him Editor Alison M. Bennie Steve Laffey ’84 returned to his hometown of Cranston, Rhode Island, after much of what he wanted to know, he was also kind of concerned that knowing twenty years of success in other places. Concerned about the state of would set him apart and make him therefore responsible for everything. -

Celebration of Excellence in Hospital Care

The 27th Annual Celebration of Excellence in Hospital Care March 15, 2017 Hospital Association of Rhode Island 5:30 p.m. Reception 405 Promenade Street, Ste. C Providence, Rhode Island 02908 6:30 p.m. Awards Ceremony p 401-443-2803 / f 401-533-9328 www.HARI.org Crowne Plaza, Warwick, RI HARI Affiliate Members Aetna Applied Management Systems AstraZeneca Merritt Hawkins Rhode Island College Truven Health HARI Member Hospitals Welcome to the 27th Annual Celebration of Excellence in Hospital Care. Butler Hospital Kent Hospital Tonight is a recognition of the heroes in our hospitals - employees who go above and beyond each day to ensure Fatima Hospital superior patient care. Landmark Medical Center We will also present the Edward J. Quinlan Award Memorial Hospital of RI for Patient Safety Excellence. Providence VA Medical Center The awards ceremony will commence at 6:30 p.m. Roger Williams Medical Center Enjoy the evening! South County Hospital Westerly Hospital Women & Infants Hospital Butler Hospital Edward J. Quinlan Award for Patient Safety Excellence Micaela Condon, Patient Assessment Services Clinician The Edward J. Quinlan Award for Patient Safety Excellence honors Micaela began her career in 2006 as a mental health worker/ a hospital unit and/or team that has implemented an initiative that has achieved measurable results in improving quality and patient safety. CNA at Butler Hospital. In 2010, she pursued her master’s degree in social work at Rhode Island College. Upon graduation, she transitioned to care planner and gained experience in Butler’s Young Adult Partial Hospital Program. After more than a decade of service, Micaela now works as a member of the multidisci- plinary team of the newly opened Hall @ Center House. -

February 13, 2007

Ana Tuya Fulton, MD November 3, 2020 Curriculum Vitae Ana Tuya Fulton, MD, MBA, FACP, AGSF (Ana Cristina Tuya, MD) PERSONAL INFORMATION Business Address: Kent Hospital 455 Tollgate Road Warwick RI 02886 Business Phone: 401-736-4287 Business Fax: 401-736-1071 Business Email: [email protected] or [email protected] EDUCATION Undergraduate 1993-1997 The George Washington University Washington DC. Major in Psychology, BA. Graduation Summa Cum Laude Early Acceptance to The George Washington University School of Medicine. Medical School 1997-2001 The George Washington University School of Medicine Washington DC. Awarded MD and graduated with distinction on May 20, 2001. Graduate 2/2020-11/2020 Masters of Business Administration, Healthcare Management Western Governor’s University POSTGRADUATE TRAINING Residency 2001-2004 Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital, Rhode Island. Internal Medicine 2001-2004 PGY 1-3. 593 Eddy Street JB 0100 Providence RI 02903. Chief Residency 2004-2005 Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital. PGY 4 Internal Medicine. Fellowship 2005-2006 Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital, Division of Geriatrics. Geriatric Medicine Fellowship 2007-2008 Brown University Harriet W. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning – Certificate I POSTGRADUATE HONORS AND AWARDS 2005 Haffenreffer Fellow in Medical Sciences in the Internal Medicine Program. Awarded for work done chief residency year 7/2004- 6/2005 1 Ana Tuya Fulton, MD 2006 Chosen as Futures Program Participant for the 2006 American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) Annual Meeting 2007 Geriatric Academic Career Award (GACA) from HRSA awarded Three year funding for academic geriatricians. 2011 Recommended for Invited Fellowship to American College of Physicians. Elected a Fellow of the College March 1, 2011 2016 John A. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenneth A. Williams, M.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenneth A. Williams, M.D. BUSINESS ADDRESS Rhode Island Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine Division of Emergency Medical Services 55 Claverick St. First Floor Providence, RI 02903 Telephone: 401-444-2739 Fax: 401-444-4307 [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Director, Division of Emergency Medical Services Program Director, EMS Fellowships Medical Director, LifePACT Critical Care Transport Team Medical Director, Ambulance Services, Rhode Island Hospital Professor of Emergency Medicine (Clinician Educator Track) The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University Senior Medical Officer, RI-1 Disaster Medical Assistance Team USCG Liaison, RI DMAT/MRC Medical Director, RI Department of Health, Center for Emergency Medical Services, Division of Preparedness, Response, Infectious Disease & EMS Councilor at Large, Rhode Island Medical Society Immediate Past Chair, Medical Director’s Council, National Association of State EMS Officials Member, US Coast Guard Auxiliary, District 1 NR, Division 07, Flotilla 08 Member number 1248895 EMPLID 1248895 Status: IQ / operational support Boat Crew Certified & Qualified, USCG 45 RB-M Assistant Clinical Professor, Rochester Institute of Technology EDUCATION Undergraduate: Hampshire College, Amherst, MA BA, 1977 Postgraduate University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA Postgraduate Science Studies, 1980 University of Massachusetts, Amherst Medical Informatics / Artificial Intelligence / Knowledge Engineering, 1997 Medical School: University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, -

Recognition Dr

PEOPLE Recognition Dr. Christy Dibble Earns Dr. Joseph DiMase Memorial Healthcare Professional Award PROVIDENCE – CHRISTY DIBBLE, DO, director of Women Dr. James F. Padbury Honored & Infants’ Center for Women’s Gastrointestinal Health and with Silver Rattle Award assistant clinical professor in the Department of Medicine at The Warren Alpert Medical PROVIDENCE – JAMES F. PADBURY, MD, pediatrician-in-chief School of Brown University, has and chief of Neonatal/Perinatal Medicine at Women & Infants received the Dr. Joseph DiMase Hospital of Rhode Island and the Memorial Healthcare Profes- William and Mary Oh-William sional Award from the Partner- and Elsa Zopfi Professor of Pediat- ship to Reduce Cancer in Rhode rics for Perinatal Research at The Island, Rhode Island Department Warren Alpert Medical School of of Health. Brown University, was honored Dr. Dibble received the award with the Silver Rattle Award from for her work as physician-chair the Rhode Island Healthy Moth- of the Rhode Island Screening ers, Health Babies Coalition at the and Detection Workgroup of the WOMEN & INFANTS coalition’s annual May Breakfast. Partnership to Reduce Cancer in Rhode Island, part of Rhode Since 2001, the Silver Rattle Island’s Cancer Control Plan. The focus of the workgroup, WOMEN & INFANTS Award has been given to someone on which Dr. Dibble has been chair since 2005, is reducing or an organization that has “shaken up the system for Rhode colorectal cancer and eliminating disparities in screening and Island mothers and babies.” Dr. Padbury was awarded by the detection in Rhode Island. This award is to recognize a state’s coalition specifically for his continued efforts to develop the comprehensive cancer control coalition that has successfully single-family room neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at achieved evidence-based and measurable impact in projects Women & Infants Hospital, a Care New England hospital.