D.2 Residential Styles and Forms the Single-Family Dwelling in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUILDING CONSTRUCTION NOTES.Pdf

10/21/2014 BUILDING CONSTRUCTION RIO HONDO TRUCK ACADEMY Why do firefighters need to know about Building Construction???? We must understand Building Construction to help us understand the behavior of buildings under fire conditions. Having a fundamental knowledge of buildings is an essential component of the decisiondecision--makingmaking process in successful fireground operations. We have to realize that newer construction methods are not in harmony with fire suppression operations. According to NFPA 1001: Standard for FireFighter Professional Qualifications Firefighter 1 Level ––BasicBasic Construction of doors, windows, and walls and the operation of doors, windows, and locks ––IndicatorsIndicators of potential collapse or roof failure ––EffectsEffects of construction type and elapsed time under fire conditions on structural integrity 1 10/21/2014 NFPA 1001 Firefighter 2 Level ––DangerousDangerous building conditions created by fire and suppression activities ––IndicatorsIndicators of building collapse ––EffectsEffects of fire and suppression activities on wood, masonry, cast iron, steel, reinforced concrete, gypsum wallboard, glass and plaster on lath Money, Money, Money….. Everything comes down to MONEY, including building construction. As John Mittendorf says “ Although certain types of building construction are currently popular with architects, modern practices will be inevitably be replaced by newer, more efficient, more costcost--effectiveeffective methods ”” Considerations include: ––CostCost of Labor ––EquipmentEquipment -

OPEN STORY Opening up the Main Floor and Adding Custom Stor- Age Solutions Lets the Small Home Function Like a Much Larger Space

DECORATING o stay or not to stay? That was the question facing this family. Their challenge: A total revamp turns a cramped, they were growing, but their 1920s Montreal row house wasn’t. Was a move to disorganized main floor into a the suburbs necessary or could a reno turn their house into a dream home? “Young families often come to this fork in the road,” says designer Eugenia flowing family space with tons of Triandos of Hibou Design & Co. “In this case, they truly wanted to stay.” But with storage and style. two young boys, the tight layout was rife with storage issues, and the outdated closed-off kitchen (and its constantly used backyard door) was frustrating. TEXT BETHANY LYTTLE “Our goal became to change their lives for the better but not change the square footage,” PHOTOGRAPHY DREW HADLEY Tsays Eugenia, who set about opening up the main floor and adding plenty of custom stor- age. She elevated the chronically chaotic front entrance into a gloriously organized space, and turned the kitchen into both a haven for family togetherness and a gateway to outdoor play. Then she turned her attention to aesthetics. Bistro-style tufting glammed up the ban- quette and graphic wallpaper jazzed up the seating nooks. “These are eye-catchers, the DON’T crowning glory on a space designed, first and foremost, to make life for my clients easier, MOVE, prettier, and a lot more carefree.” OPEN STORY Opening up the main floor and adding custom stor- age solutions lets the small home function like a much larger space. -

DATE ISSUED: August 10, 2017 REPORT NO

The City of San Diego Report to the Historical Resources Board DATE ISSUED: August 10, 2017 REPORT NO. HRB-17-047 HEARING DATE: August 24, 2017 SUBJECT: ITEM #5 – William and Carrie Old Bungalow Court RESOURCE INFO: California Historical Resources Inventory Database (CHRID) link APPLICANT: Atlas at 30th Street LLC represented by Scott A. Moomjian LOCATION: 2002-2010 30th Street, Golden Hill Community, Council District 3 APN 539-155-13-00 DESCRIPTION: Consider the designation of the William and Carrie Old Bungalow Court located at 2002-2010 30th Street as a historical resource. STAFF RECOMMENDATION Designate the William and Carrie Old Bungalow Court located at 2002-2010 30th Street as a historical resource with a period of significance of 1948 under HRB Criteria A and C. This recommendation is based on the following findings: 1. The resource is a special element of Golden Hill and San Diego’s historical and architectural development and retains integrity to its 1948 date of construction and period of significance. Specifically, the resource embodies the character defining features of a recognized variety of bungalow court, is one of a finite and limited number of bungalow courts remaining which reflect the early- to mid-20th century development of multi-family housing in Golden Hill and San Diego, and retains integrity for that association. 2. The resource embodies the distinctive characteristics through the retention of character defining features of a Minimal Traditional style bungalow court and retains a good level of architectural integrity from its 1948 date of construction and period of significance. Specifically, the resource retains an original attached full court layout; gabled roof forms with boxed eave and minimal overhang; wood shingle cladding accented with brick; multi- light wood double hung and fixed windows; and modest, compact size with simple plan forms. -

Geodesic Dome Roof

GEODESIC DOME ROOF The HMT Geodesic Dome features a clear-span, all-aluminum, lightweight, corrosion-resistant structure which sets a new standard for performance in aluminum geodesic domes. HMT’s unique overlapping-panel design and attention to details at critical locations all result in a cost-effective solution that provides superior protection of your stored product. The HMT Geodesic Dome can be installed in-service and its superior design was developed under the guidance of API 650, appendix G and AWWA D-108. Key benefits: Key design features: The HMT Geodesic Dome’s advanced tBatten bar and gasket assembly completely technology provides excellent benefits. Here’s encapsulate panel edges for unparallelled how: sealing Most effective leak-protection solution— tOverlapping panels ensure additional Engineered for maximum weather-tightness for protection against weather both new tanks and retrofits tHub designed with three levels of sealing to Low maintenance — Aluminum alloys are ensure maximum leak protection corrosion resistant and don’t require painting like steel fixed roofs tHub can be easily removed for inspection or Emissions reduction — reduces wind-induced adjustment of IFR support chains vapor loss, aids in odor control and provides tOptions for fixed or sliding rim connections significant emission credits; for light products such as gasoline, a dome installed over an EFR tCan easily handle the weight of suspended can cut emissions by over 90% aluminum internal floating roofs In-service installation — Can be erected on tIndustry-leading 3D design software for the ground beside the tank or on an EFR and maximum accuracy and shorter design time lifted into place Custom engineered— To accommodate a wide range of spans and loading conditions Protecting your world, one tank at a time™ www.hmttank.com THE HMT GEODESIC DOME DESIGN HMT’s design incorporates features which dramatically Triple seal hub design improve upon existing technology. -

Dramatic Loft, Main Level Master Bedroom with Walk in Closet. Large Family Room, Dining Room and Flowing Kitchen with Pantry. Tw

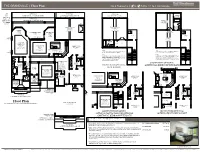

The Piedmont Triad’s Premier Builder Aspen Dramatic loft, main level master bedroom with walk in closet. Large family room, dining room and flowing kitchen with pantry. Two story family room open to second floor. Bonus room/bedroom over the garage. Bedrooms: 3 Full Baths: 2 Half Baths: 1 Square Footage: 2.220 Stories: 2 Housing Opportunity. Prices floor plans & standard features are subject to change without notice. The elevations, floor plans & square footages shown are for illustrative purposes only. Structural or other modifications which are in accordance with applicable building codes may be made as deemed necessary or appropriate given the elevation to other characteristics of the lot on which the home is constructed. The dimensions and total square footage shown are approximations only. Actual dimensions and total square footage of the home constructed may vary. WWW.GOKEYstoNE.COM | The Piedmont Triad’s Premier Builder Optional Sunroom OPTIONAL BAY WINDOW Loft Bedroom Breakfast Master (Optional Kitchen Bedroom 4) 2 Nook Suite OPTIONAL Optional F Sunroom OPTIONAL BAY WINDOW SEPARATE SHOWER OPTIONAL FIREPLACE 60" VANITY W D W Open to OPTIONA TRANSO WINDOW Family PICTURE Below Room Loft Bedroom M Breakfast Master L (Optional Kitchen Bedroom 4) 2 Suite 42" GARDEN Nook TUB OPTIONAL F Luxury Master Bath Option SEPARATE SHOWER OPTIONAL Optional FIREPLACE 60" VANITY W Sunroom OPTIONAL BAY WINDOW D 2 CaW r Open to OPTIONA TRANSO WINDOW Family PICTURE Bedroom Below Room Garage 3 M L 42" GARDEN TUB Luxury Master Loft Bedroom Breakfast Master Bath Option (Optional Kitchen Bedroom 4) 2 Nook Suite OPTIONAL F First Floor Plan Second Floor Plan 2 Car Bedroom Garage SEPARATE 3 SHOWER OPTIONAL FIREPLACE 60" VANITY W D W Open to OPTIONA TRANSO WINDOW Family PICTURE Below Room M L First Floor Plan 42" GARDEN Second Floor Plan TUB Luxury Master Bath Option 2 Car Bedroom Garage 3 Aspen First Floor Plan Second Floor Plan WWW.GOKEYstoNE.COM | . -

The Houses of Grant Neighborhood Salem, Oregon

The Houses of Grant Neighborhood Salem, Oregon The Houses of Grant Neighborhood By Kirsten Straus and Sean Edging City of Salem Historic Planning Division and Grant Neighborhood Association 2015 Welcome to The Grant Neighborhood! This guide was created as a way for you and your family to learn more about the historic city of Salem and within that, the historic neighborhood of Grant! This neighborhood boasts a diverse collection of beautiful and historic homes. Please use this guide to deci- pher the architectural style of your own home and learn more about why the Grant neighborhood is worth preserving. This project has been completed through a combined effort of the City of Salem Historic Planning Division, The Grant Neighborhood Association and Portland State University Professor Thomas Hubka. For more information, contact either the City of Salem Historic Plan- ning Division or The Grant Neighbor- hood Association. City of Salem Historic Planning Division Kimberli Fitzgerald: [email protected] 503-540-2397 Sally Studnar: [email protected] 503-540-2311 The Grant Neighborhood Association www.grantneighborhood.org GNA meetings are held the first Thursday of each month at the Grant Community School starting at 6:15 pm. All are welcome to at- tend! The Grant Neighborhood Contents The History of Salem and Grant Neighborhood 6 Map of The Grant Neighborhood 10 Housing Styles 12 Feature Guide 12-13 Early Settlement 14 Bungalow 18 Period Revival 24 Post WWII 28 Unique Styles and Combinations 31 Multi-Family 32 Historic Grant Buildings 34 Neighborhood Narrative 38 Designated Homes 40 Further Reading and Works Cited 42 5 The Grant Neighborhood The History of Salem and Grant According to historic records dating back to 1850, North Salem began developing in the area north of D Street. -

Basic Technical Rules the Nubian Vault (Nv)

PRODUCTION CENTRE INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME BASIC TECHNICAL RULES v3 BASIC TECHNICAL RULES THE NUBIAN VAULT (NV) TECHNICAL CONCEPT THE NUBIAN VAULT ASSOCIATION (AVN) ADVICE TO MSA CLIENTS Version 3.0 SEASON 2013-2014 COUNTRY INTERNATIONAL Association « la Voûte Nubienne » - 7 rue Jean Jaurès – 34190 Ganges - France February 2015 www.lavoutenubienne.org / [email protected] / +33 (0)4 67 81 21 05 1/14 PRODUCTION CENTRE INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME BASIC TECHNICAL RULES v3 CONTENTS CONTENTS.............................................................................................................2 1.AN ANCIENT TECHNIQUE, SIMPLIFIED, STANDARDISED & ADAPTED.........................3 2.MAIN FEATURES OF THE NV TECHNIQUE........................................................................4 3.THE MAIN STAGES OF NV CONSTRUCTION.....................................................................5 3.1.EXTRACTION, FABRICATION & TRANSPORT OF MATERIAL....................................5 3.2.CHOOSING THE SITE....................................................................................................5 3.3.MAIN STRUCTURAL WORKS........................................................................................6 3.3.1.Foundations........................................................................................................................................ 6 3.3.2.Load-bearing walls.............................................................................................................................. 7 3.3.3.Arches in load-bearing -

Distinguishing Standard Features

DISTINGUISHING STANDARD FEATURES ELEGANT EXTERIORS ARE EASY TO MAINTAIN OLD WORLD MOLDING & MILLWORK THE PERSONAL TOUCH Ultra- Exclusive 10 acre Gated Enclave Situated in X-Large 6 ¾” 1 Piece Crown Molding in Foyer, Floor Plans Offer Plenty of Flexibility to a Beautiful Country Setting in Close Proximity to Dining Room and Formal Powder Room. Personalize the Home with Custom Designs and Shopping Hubs, Cultural Areas and Events, Fine 7 ¼” Baseboards, 3 ¼”Casing for Windows and Finishes Dining, and More Doors Buyers may Further Customize the Home by Award-Winning and Nationally Recognized West Continental Style, 2 panel Solid Core Interior Choosing from a Vast Array of Styles and Chester Area School District – Rustin High School Doors with Aged Bronze Hardware throughout the Finishes for all Cabinetry and Countertops Quick and Easy Access to All Major Home Extensive Collection of Species Hardwood Thoroughfares Coffered Ceiling with 1 Piece Crown Molding Flooring, Ceramic Tile Styles and Unique Prestigious Homes in a Private Setting with Large Hardware to Complement the Buyer’s Specific Home sites Design Ideas Stone and James Hardie HardiePlank® Lap SOPHISTICATED BATHS Siding SAFETY FIRST FOR EVERY FAMILY Historic Stone Entrance Walls Century Cabinetry Flagstone Front Porch with Brick Paver Granite Countertop in Master Bath Hardwired Smoke Detectors with Battery Backup Walkways and Lush Landscaping Frameless Shower Door in Master Bath Smoke/Carbon Monoxide Detectors on each Public Water 6’ Soaking Tub in Master Bath Floor Kohler 24” Memoirs Pedestal Sink in Powder Tankless Hot Water Heater EXQUISITE INTERIORS Room Interior/Exterior Basement Drain System Five Bedrooms, Three Full Baths and a Powder ENERGY EFFICIENT CONSTRUCTION QUALITY CONSTRUCTION Room in Most Models Walk out Finished Basement (1200 +/- sq. -

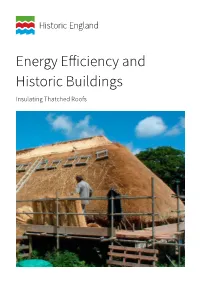

Insulating Thatched Roofs This Guidance Note Has Been Prepared and Edited by David Pickles

Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings Insulating Thatched Roofs This guidance note has been prepared and edited by David Pickles. It forms one of a series of thirteen guidance notes covering the thermal upgrading of building elements such as roofs, walls and floors. First published by English Heritage March 2012. This edition (v1.1) published by Historic England April 2016. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Illustrations drawn by Simon Revill. Our full range of guidance on energy efficiency can be found at: HistoricEngland.org.uk/energyefficiency Front cover: Thatch repairs in progress. © Philip White. Summary This guidance provides advice on the principles, risks, materials and methods for insulating thatched roofs. There are estimated to be about fifty thousand thatched buildings in England today, some of which retain thatch which is over six hundred years old. Thatching reflects strong vernacular traditions all over the country. Well-maintained thatch is a highly effective weatherproof coating as traditional deep thatched eaves will shed rainwater without the need for any down pipes or gutters. Locally grown thatch is a sustainable material, which has little impact on the environment throughout its life-cycle. It requires no chemicals to grow, can be harvested by hand or using traditional farm machinery, requires no mechanical processing and therefore has low embodied energy and can be fixed using hand tools. At the end of its life it can be composted and returned to the land. Thatch has a much greater insulating value than any other traditional roof covering. With the right choice of material and detailing, a well-maintained thatched roof will keep a building warm in winter and cool in summer and has the added advantage of being highly sound-proof. -

Floor Plan 3 to 4 Bedrooms | 2 2 to 3 2 Baths | 2- to 3-Car Garage

1 1 THE GRANDVILLE | Floor Plan 3 to 4 Bedrooms | 2 2 to 3 2 Baths | 2- to 3-Car Garage OPT. OPTIONAL OPTIONAL OPTIONAL WALK-IN EXT. ADDITIONAL COVERED LANAI EXPANDED FAMILY ROOM EXTERIOR BALCONY CLOSET PRIVACY WALL AT OPTIONAL ADDITIONAL EXPANDED COVERED LANAI BEDROOM 12'8"X12'6" COVERED VAULTED CLG. OPT. LANAI FIREPLACE FAMILY ROOM BONUS ROOM BATH VAULTED 21'6"X16' 18'2"X16'1" CLG. 9' TO 10' SITTING 10' TO 13'1" VAULTED CLG. VAULTED CLG. OPTIONAL AREA COVERED LANAI A/C DOUBLE DOORS A/C 10' CLG. BREAKFAST 10' CLG. AREA 9'X8' MECH. MECH. 10' CLG. OPT. SLIDING OPT. GLASS DOOR LOFT WINDOW 18'2"X13' 9' TO 10' BATH VAULTED CLG. MASTER 9' CLG. 9' CLG. BEDROOM CLOSET 22'X13'4" 10' CLG. LIVING ROOM BEDROOM 2 DW OPT. 10' TO 10'8" 14'X12' 11'8"X11'2" 10' CLG. COFFERED CLG. 10' CLG. DN OPT. 10' TO 10'8" GOURMET KITCHEN DN COFFERED CLG. NOTE: NOTE: OPT. 14'4"X13' MICRO/ THIS OPTION FEATURES AN ADDITIONAL 483 SQ. THIS OPTION FEATURES AN ADDITIONAL 560 SQ. WINDOW 10' CLG. WALL FT. OF AIR CONDITIONED LIVING AREA. FT. OF AIR CONDITIONED LIVING AREA. OVEN REF. NOTE: NOTE: PANTRY SPACE OPTION 003 INTERIOR WET BAR, 008 DRY BAR, 021 CLOSET OPTION 003 INTERIOR WET BAR, 008 DRY BAR, 032 ADDITIONAL BEDROOM WITH BATH, 806 BONUS ROOM, 806 ALTERNATE KITCHEN LAYOUT, ALTERNATE KITCHEN LAYOUT, AND 812 BUTLER AND 812 BUTLER PANTRY CANNOT BE 10' CLG. 10' CLG. PANTRY CANNOT BE PURCHASED IN PURCHASED IN CONJUNCTION WITH THIS OPTION. -

Fashion, Quality, Value and Safety™

PRODUCT CATALOG 2020 Fashion, Quality, Value and Safety™ v.5.08.20 Choosing from a wide variety of office and home office furnture is exciting. Our travels around the world have opened our eyes to color, design and many wonderful cultures throughout the globe. These experiences have helped us develop our Style Guides™ giving you the opportunity to choose furniture that expresses your personal style. We offer Quick-to-Assemble™ technology, specially designed for you throughout many of our collections for easier, faster assembly and a wonderful experience overall. Enjoy these products that are made to last with three-year or six-year warranties from kathy ireland® Home by Bush Furniture and Bush Business Furniture Office bykathy ireland®. Bush Industries is a leading and prestigious manufacturer with a 60-year successful history. kathy ireland® Worldwide missions are: “...solutions for families, especially busy moms.”™ “...solutions for people in business.”™ Fashion, Quality, Value and Safety™ are our four promises to you. Each design is tested to meet the highest industry standards. In many of our products, we provide child safety features including rounded edges and soft close hinges. We have confidence that you’ll findkathy ireland® Home by Bush Furniture a wonderful fit for your home and office. You may also experience coordinating lighting, flooring, accessories and other beautiful designs throughout our other brands that will complete your personal environment. We know that you have many choices for home and office furniture, and we’re delighted that you’ve chosen us for this special moment. OUR PROMISE ATRIA combines modern and industrial styles with the durability you depend on in your home or professional office. -

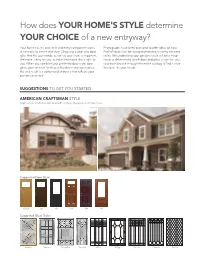

How Does YOUR HOME's STYLE Determine YOUR CHOICE of a New Entryway?

How does YOUR HOME'S STYLE determine YOUR CHOICE of a new entryway? Your home has it's own style and every component works Photographs have been provided to offer ideas on how in harmony to create that style. Choosing a door and door ProVia® doors can be incorporated onto a variety of home glass that fits your needs, as well as your style, is important. styles. We understand your personal style will be a major We make it easy for you to make the choice that's right for factor in determining which door and glass is right for you, you. When you combine your preferred door style, door so please browse through the entire catalog to find a style glass, paint or stain finish, plus hardware and accessories, that best fits your needs. the end result is a customized entryway that reflects your personalized style. SUGGESTIONS TO GET YOU STARTED AMERICAN CRAFTSMAN STYLE Might include: Craftsman, Arts and Crafts, Cottage, Bungalows and Prairie House. Suggested Door Styles: 420-DS 420 430 419 006 440 Suggested Glass Styles: Berkley Laurence Carrington Tacoma Aztec Vintage Lincoln Cambria Westin CLASSIC/COLONIAL STYLE Might include: Federal, Cape Cod, Dutch, Farmhouse, Traditional, Georgian and Gambrel. Suggested Door Styles: 460 430 440 150 230 006 400 419 Suggested Glass Styles: Symphony Somerset Constance Jewel Eclipse Florence Beveled Tuscany Twilight Haven OLD WORLD STYLE Might Include: Victorian, Queen Anne, Neo-eclectic, Mediterranean, European and French Countryside. Suggested Door Styles: 449 460 350 437 439 243 008P 002C-449 002CP-437 003 Suggested Glass Styles: Cheyenne Carrington Carmen Barcelona Esmond Carlisle Tulips Harmony Americana Blossoms Cambria Westin MODERN/CONTEMPORARY STYLE Might include: Ranch, Split Level, International, Rectangular, Geometric and Curved Architecture.