Clinical Emergency: Are You Ready in Any Setting?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crash Cart Drawers

15MS3130 ASC Guide_Layout 1 4/7/15 8:54 PM Page 97 Emergency Crash Cart Essentials for Physician Office and Healthcare Facilities THIRD DRAWER-Circulation: CC Qty. Inventory Component Order# crash cart 2 Lasix 40mg/10mL – CC Drugs 1 Magnesium Sulfate 5 Gm./10mL CC Drugs drawers FOURTH DRAWER-Circulation (IV): CC Qty. Inventory Component Order# 3 Gloves- Nitratex® Small Sterile PF 100 /Box 685-5866 3 Gloves- Nitratex® Med Sterile PF 100/Box 685-7913 3 Gloves- Nitratex® Large Sterile PF 100/Box 685-4461 Each Tape-Hypafix 2" x 2 Yds. Roll 925-4928 2 Introcan® Safety IV Catheter 22 Ga. x 1” Each 507-5531 2 Introcan® Safety IV Catheter 20 Ga. x 1” Each 507-5995 1 Arterial Blood Gas Kit 25 Ga. x ⅝" 100/Case 245-2041 1 Tourniquet Latex-Free, 18” x 1” 25/Box 270-3884 5 Alcohol Swabs- BD Swabsticks 100/Box 987-5706 2 Syringes 60mL 50/Box 112-6152 2 Syringes 20mL 50/Box 112-6151 5 Syringes 10mL 100/Box 900-4476 5 Syringes 5mL 100/Box 900-4477 5 Syringes 3mL 100/Box 900-4475 10 Needles 18 Ga. x 1” 100/Box 900-4469 2 Injectable Saline 30mL CC Drugs Each Conductivity Gel-Spectra™ 360 8.5 oz. 727-6353 FIRST DRAWER-Medications: CC Qty. Inventory Component Order# FIFTH DRAWER–Intubation: CC Qty. Inventory Component Order# 2 Adenosine 3mg 2mL CC Drugs 1 Amiodarone HCl 50mg 3mL CC Drugs 36 Dantrium 20mg – Each CC Drugs 1 Atropine Sulfate 10mL CC Drugs 1 Laryngoscope – Welch-Allyn Handle Each 566-6530 1 Calcium Gluconate 10% 10mL CC Drugs 1 Miller Blade #2 – Disposable Each 857-5266 1 Dobutamine 250mg 20mL CC Drugs 1 Miller Blade #3 – Disposable Each 857-3605 -

ACLS: Crash Course in Crash Carts

ACLS: Crash course in crash carts By Andrew Herman, MS, RN How proficient would you really be if a code situa- the setting at 2 mA above that capture point. The tion occurred? Even while keeping your skills up to patient should now be ready for immediate transfer date with advanced cardiovascular life support for more definitive care, such as internal pacing. (ACLS) recertification, it’s possible for nurses to find themselves out-of-practice. This article outlines Tachycardia the magic numbers associated with ACLS, the tools At the other extreme, tachycardia can cause the and medications you’ll find in the crash cart, and patient’s cardiac perfusion to drop because the treatment guidelines to follow in a code situation. heart is beating faster than it’s designed to do. This brings us to our next ACLS magic number: Bradycardia 150. A heart rate above 150 beats/minute is the Let’s begin with a bradycardia situation. Here, we point at which electrical therapy should be consid- encounter one of our ACLS magic numbers: 90. As ered. Supraventricular tachycardia, rapid atrial a rule, a patient with a dysrhythmia who still flutter, or rapid atrial fibrillation will show a maintains a systolic BP of 90 mm Hg or higher can narrow QRS complex on the ECG of less than receive treatment with medications. But, if the sys- 0.12 seconds, which equals three of the small tolic BP decreases to below 90, we have to set up 0.04-second squares on the ECG graph. Ventricular for electrical therapy. tachycardia will have a very wide QRS complex of Ideally, crash carts are standardized. -

Advances in the Acute Management of Cardiac Arrest

September 2008 Advances In The Acute Volume 10, Number 9 Management Of Cardiac Arrest Authors Bakhtiar Ali, MD Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, GA A 47-year-old man presents with nonspecific chest discomfort intermittently over the past 3 days. Episodes are not related to exertion and last 10 to 30 A. Maziar Zafari, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA minutes. He has a history of hypertension and smokes 1 pack per day. In the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, Georgia; Emory University School of Medicine, Division of ED, he is pain free and has an ECG with evidence of left ventricular hypertro- Cardiology, Atlanta, GA phy and j-point elevation. You doubt that he has an acute cardiac syndrome but Peer Reviewers decide to err on the conservative side and admit him to your observation unit. The patient looks well, his first troponin is negative, and the monitor continues Bentley J. Bobrow, MD, FACEP Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Department to show a normal sinus rhythm. Two hours later you go to check on the patient of Emergency Medicine, College of Medicine, Mayo and find him disconnected from his monitor, unresponsive, and with no pulse Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Medical Director, Bureau of Emergency Medical Services and Trauma System, Arizona (no wonder there was so much beeping coming from the obs unit). The nurse Department of Health Services, Phoenix, AZ has been on break for the past 30 minutes, and due to “sick calls” there was no cross coverage. You call for help which doesn’t immediately come, and you Barbara K. -

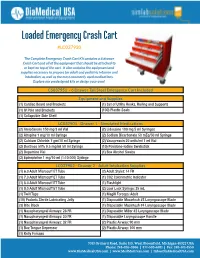

Loaded Emergency Crash Cart

Loaded Emergency Crash Cart #LC037930 The Complete Emergency Crash Cart Kit contains a 6 drawer Crash Cart and all of the equipment that should be attached to or kept on top of the cart. It also contains the equipment and supplies necessary to prepare for adult and pediatric infusion and intubation, as well as the most commonly used medications. Explore our predesigned kits or design your own! CS037951 - 6 Drawer Tall Steel Emergency Cart Included Equipment and Supplies (1) Cardiac Board and Brackets (1) Set of Utility Hooks, Railing and Supports (1) IV Pole and Brackets (100) Plastic Seals (1) Collapsible Side Shelf LC037901 - Drawer 1 - Simulated Medications (2) Amiodarone 150 mg/3 ml Vial (2) Lidocaine 100 mg 5 ml Syringes (2) Atropine 1 mg/10 ml Syringe (2) Sodium Bicarbonate 50 mEq/50 ml Syringe (2) Calcium Chloride 1 gm/10 ml Syringe (2) Vasopressin 20 units/ml 1 ml Vial (2) Dextrose 50% 0.5 mg/ml 50 ml Syringe (10) Povidone-Iodine Swabstick (2) Dopamine Vial (1) Box Alcohol Swabs (2) Epinephrine 1 mg/10 ml (1:10,000) Syringe LC037902 - Drawer 2 - Adult Intubation Supplies (1) 6.0 Adult Microcuff ET Tube (2) Adult Stylet: 14 FR (1) 7.0 Adult Microcuff ET Tube (1) CO2 Colorimetric Indicator (1) 8.0 Adult Microcuff ET Tube (1) Flashlight (1) 9.0 Adult Microcuff ET Tube (2) Luer Lock Syringe: 35 mL (1) Twill Tape (1) Magill Forceps: Adult (10) Packets Sterile Lubricating Jelly (1) Disposable Macintosh #3 Laryngoscope Blade (3) Bite Block (1) Disposable Macintosh #4 Laryngoscope Blade (1) Nasopharyngeal Airways: 26 FR (1) Disposable -

Objectives In‐Hospital Cardiac Arrests

9/21/2017 Streamlining the Crash Cart Model: Less is More Elizabeth Short, Pharm.D., BCCCP* Pharmacy Practice Coordinator‐ Clinical Services (non‐oncology) PGY1 Residency Coordinator Northwestern Memorial Hospital Chicago, Illinois *No conflicts of interest to disclose Objectives • Pharmacist 1. Identify resuscitation processes that are critical to survival from sudden in‐hospital cardiac arrest. 2. Describe the role of the pharmacist in a mobile crash cart model. • Technician 1. Identify the two most important steps in a cardiac arrest. 2. Explain the difference between a standard crash cart model and a mobile crash cart model. In‐hospital Cardiac Arrests • In‐hospital 1 – Incidence: 209,000 – Survival rate: 24.8% • Chicago airports 2 – Incidence: 18 – Survival rate: 61% • 100% received chest compressions • Time to shock < 5 minutes in 2/3 of people 1. http://cpr.heart.org/AHAECC/CPRAndECC/General/UCM_477263_Cardiac‐Arrest‐Statistics.jsp 2. Sherry L. Caffrey. N Engl J Med. 2002 Oct 17;347(16):1242‐7. 1 9/21/2017 Chain of Survival • Successful resuscitation requires early 1 – Recognition of cardiopulmonary arrest – Activation of trained responders – Chest compressions – Defibrillation when indicated – Advanced life support (ALS) 1. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/95/8/2211 Chain of Survival • Goal – To safely and efficiently improve the resuscitation process • Metrics – Number and severity of incident reports related to insufficient supplies – Percent of patients defibrillated within two minutes of recognition of cardiac arrest 1,2 1. Ewy GA, Ornato JP. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Mar 15;35(4):832‐46. 2. Cummins et al. Circulation. 1991 May;83(5):1832‐47. -

Crash Cart Inventory Checklist

CRASH CART INVENTORY CHECKLIST Top of Cart Defibrillator / Adult / Pediatric Paddles Suction Machine with Yankauer attached Lead wires, Electrodes Stethoscope (1), BP cuff Adult (1), Pediatric (1) ACLS Algorithms / Drug List IV Pole with Ambu Bag (1) / Mask / Face Shield / Goggles / NC (1), Non- Rebreather (1) / Adult O2 Mask (1) / Peds O2 Mask (1) Sharps Box (1) Code Blue Record / Charting Board / Crash Cart Checklist ACLS Quick Review Guide Conduction Gel (1) Adult Pacer Pads (1) Side of Cart Oxygen Tank with regulator Back of Cart CPR Back Board Power Strip Drawer #1 Adult Medications Adenocard 6mg vial (3) Amiodorone (with excel bag or glass bottle) (3) Atropine 1mg / 10mL PFS (2) Calcium Chloride 10% 1gm / 10mL PFS (2) Dextrose 50% / 50mL PFS (2) Dobutamine Drip 500mg / 250mL (1) Dopamine Drip 400mg / 250mL (1) Ephedrine 50mg / 1mL vial (2 ) Epinephrine 1:1,000 AMP (2) Epinephrine 1:10,000 / 10mL PFS (6) Furosemide (Lasix) 40mg vial (2) Isuprel 0.2mg / mL AMP (1) Lidocaine Drip 1g / 250mL (2 ) Lidocaine 2% 100mg / 5mL PFS (2 ) Magnesium Sulfate 50% 10mL PFS (2) Neo-Synephrine HCl (Phenylephrine) 10mg / mL AMP (1) Nitroglycerine (Sublingual Spray) (1) Naloxone (Narcan) 0.4mg / mL AMP (2) Procainamide 100mg / mL (2) Romazicon 0.1mg /mL vial (1) Sodium Bicarbonate 8.4% (2) Vasopressin 20 units/mL (2) © 2011 Progressive Surgical Solutions, LLC CRASH CART INVENTORY CHECKLIST Drawer #1 (cont) Pediatric Medications Adenocard 6mg/2mL (2) Atropine 1mg/10mL in syringe (2) Calcium chloride 10% 1gm/10mL -

Chapter 22 Emergency Medication

CHAPTER 22 EMERGENCY MEDICATION KIT 22.1 HOSPITAL EMERGENCY DRUGS 1. Emergency Drugs Used in the Hospital Crash carts Resuscitation or medication trays Various emergency kits or boxes Eclampsia kit Malignant hyperthermia cart 2. Standardize Format – carts, trays or kits Specific drugs used Crash cart drugs directed by ACLS guidelines (last updated 2000) May differ for adults and pediatrics Location of drugs and supplies in the cart Staff can quickly find what is needed Education of staff on a continual basis 3. Emergency medications must be secure (TX 3.5.5) Assure medications are available when needed Prevent tampering Options Plastic break away lock or plastic wrap No lock with regular inventory to assure contents are present kept in a locked room under constant surveillance 4. Plastic locks Advantages of plastic locks Expiration date placed on lock When sealed lets staff know contents are complete and within their expiration date Staff checks seal each shift and document Once seal is broken – signifies contents removed or expired Seal intact and within expiration date – do NOT need to check contents Plastic locks MUST be controlled by the pharmacy 5. Documentation to show QA check Filled by/checked by Lot & expiration date 6. Common crash cart system in Hospital – exchange system with ready-to-go back-up carts (May use different color seal when returning used cart) 22.2 SAMPLE CRASH CART USED IN THE HOSPITAL SAMPLE POLICY: Emergency Medication and Crash Cart System POLICY: Emergency medications are consistently available, controlled, and secure in the pharmacy and patient care areas. PROCEDURE: A. Tamper Locks: 1. -

Crash Course on Crash Carts in the Ambulatory Healthcare Setting

Crash Course on Crash Carts in the Ambulatory Healthcare Setting Definition of a crash cart/crash kit Is there a standard crash cart/kit formulary? A crash cart/kit or code cart/kit is a set of trays, drawers or shelves on wheels No. The size, shape, and contents of a crash cart may be different between used for transporting and dispensing emergency medications and equipment facilities. The crash cart in an urgent care facility is typically different than the at the site of a medical emergency. A crash cart/kit is deployed to administer one in a surgical facility. The crash cart may even differ between departments life support protocols such as Advanced Cardiac Life Support/Advanced Life within the same facility. For example, an adult crash cart is set up differently Support (ACLS/ALS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS). than a pediatric crash cart. Basic crash kits, also known as emergency medical kits, are available for Recommended crash cart formularies are defined by your state and federal common medical emergencies (such as allergic reactions, opioid overdose, department of health licensing agencies as well as the appropriate accrediting and asthma) that do not require IV medications or ACLS training. These are bodies depending on facility type and procedure classifications. commonly found in family, general and dental practices. Always follow your compliance officer’s and/or medical director’s guidelines Who needs a crash cart/kit? for required contents and quantities for your specific facility and procedure categories. There are certain procedures that put a patient at risk for a medical emergency and those facilities performing those procedures are required to have a crash See A Guide to Accrediting Bodies. -

Emergency and Resuscitation Equipment, Supplies and Medications

Policies of the University of North Texas Health Science Center Chapter 14 14.308 Emergency and Resuscitation Equipment, Supplies and UNTHealth Medications Policy Statement. Certain UNT Health clinics are required to maintain specific emergency and resuscitation equipment, supplies and medications (collectively, “Crash Cart”) as approved by the Department Chair and the Quality, Patient Safety and Services Committee. UNT Health requires that all Crash Carts be adequately stocked, up-to-date and operational. Application of Policy. This policy applies to all UNT Health clinics. Definitions. None Procedures and Responsibilities. 1. All Crash Carts shall be stocked as outlined in Exhibit A. Responsible Party: Clinic Supervisor/Manager 2. Crash Carts shall be inventoried on a monthly basis and after each use to verify that all medications, supplies and equipment listed on Exhibit A are available, operational and up-to-date. The cardiac monitor and defibrillator shall be tested daily per the manufacturer’s instructions. If no discrepancies or deficiencies are noted, the Log sheets shall be completed and initialed by the staff person performing the inventory and tests. Responsible Party: Clinic Supervisor/Manager 3. Any discrepancies or deficiencies shall be noted on the Log sheets and corrected immediately. If immediate correction is not possible, alternative arrangements shall be made before patients are treated in the clinic. Responsible Party: Clinic Supervisor/Manager 4. After a Crash Cart has been used, it shall be cleaned as appropriate, inventoried and used items shall be replaced within two business days. Responsible Party: Clinic Supervisor/Manager References and Cross-references. Policy 14.303 – Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) Training Policy 14.309 – Medical Emergencies in Clinical Areas Forms and Tools. -

Emergency Cardiac Situations & Drugs

Emergency Cardiac Situations & Drugs Presented by Sarah Newlen, CPhT October 9, 2015 Emergency Cardiac Situations & Drugs Presented by Sarah Newlen, CPhT October 9, 2015 I, Sarah Newlen, have no financial relationships to disclose Objectives: For the Technician: 1.Define what is classified as an emergency situation 2.Increase your knowledge of emergency medications 3.List the indications for emergency drugs Objectives: For the Pharmacist: 1. Describe how to fully utilize the Technician in the management crash carts 2. Identify State Board of Pharmacy regulations impacting crash carts 3. Describe collaboration between Pharmacist and Technician ACLS Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support ➢ Cardiac arrest ➢ Pulmonary arrest ➢ Other life threatening situations Required Skills for ACLS ➢ Manage patient airway ➢ Initiate IV access ➢ Maintain blood circulation ➢ Read and interpret electrocardiograms ➢ Understand emergency pharmacology What is emergency therapy? An Emergency Situation ➢ Poses an immediate threat to health or life ➢ High probability of escalating to cause immediate danger to health or life ➢ Has caused health detriments or loss of life Common Emergency Conditions ➢ Ventricular Fibrillation - V-Fib ➢ Torsades de Pointes ➢ Asystole ➢ Pulseless Electrical Activity-PEA ➢ Bradycardia ➢ Tachycardia Who has seen a normal heart rhythm on an ECG? Normal heart rhythm as displayed on an ECG Ventricular Fibrillation V-Fib Fibrillation - uncontrolled twitching or quivering. Symptoms may include: ● Dizziness ● Nausea ● Pain in the chest ● Tachycardia -

Code Blue for a Patient in 4 Jones Rehabilitation Unit

CPR FACTS In the hospital setting, among participating centers in the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation quality improvement program, the median hospital survival rate from adult cardiac arrest is 18% (interquartile range, 12%–22%) and from pediatric cardiac arrest, it is 36% (interquartile range, 33%–49%). Circulation. 2013;128:417-435 CPR FACTS • In a hospital setting, survival is >20% if the arrest occurs between the hours of 7 am and 11 pm but only 15% if the arrest occurs between 11 pm and 7 am. • There is significant variability with regard to location, with 9% survival at night in unmonitored settings compared with nearly 37% survival in operating room/post anesthesia care unit locations during the day. Circulation. 2013;128:417-435 CPR FACTS • Patient survival is linked to quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). • When rescuers compress at a depth of <38 mm, survival-to-discharge rates after out-of-hospital arrest are reduced by 30%. • Similarly, when rescuers compress too slowly, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after in- hospital cardiac arrest falls from 72% to 42%. Circulation. 2013;128:417-435 SURVIVAL AFTER IN-HOSPITAL CARDIAC ARREST Girotra, NEJM 2012 SURVIVAL AFTER IN-HOSPITAL CARDIAC ARREST Girotra, NEJM 2012 SCENARIO #1 • You respond to a code blue for a patient in 4 Jones rehabilitation unit. • On arrival you find the patient in the corner of the room in a vail bed, pulseless • What do you do next? WHAT DO YOU DO? A. Freak out B. Tear open the vail bed with Hulk-like strength C. Unzip the vail bed and start chest compressions D. -

Crash Cart SOP Web Layout 1 11/7/13 9:27 AM Page 1

13MS9148 Crash Cart SOP web_Layout 1 11/7/13 9:27 AM Page 1 “The CMS ASC Conditions for Coverage mandate Most allergic reactions that occur during anesthesia Patients with atopic diseases such as asthma, eczema, specific requirements for emergency management.” are caused by antibiotics, though many reactions or allergic rhinitis are at high risk of anaphylaxis Typically, these policies include code blue response, do not have a clear cause. from food, latex, and radiocontrast. emergency transfer, and crash cart. Source: Anesthesia and Allergy, Sept. 2011 Source: Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Source – CMS A compliant crash cart is characterized by ToP of THE CART storing lifesaving equipment that is easily movable and readily accessible into all sides of defibrillator Real CPR Help™ for ALS the cart for quickly viewing and removing ® The first and only Code-Ready ® SOP equipment and drugs during a crisis situation. monitor defibrillator Stat Kit Z-1000 crash cart CRASH CART BEST PRACTICES: R-Series ALS Each 120-7737 When time is critical, your • Design a standardized crash cart that meets the needs Thermal Paper 5/Box 106-5906 ability to get the appropriate of your facility, the patient population you treat, and Spectra Gel 8.5 oz. 727-6353 medications, devices, and Stat Pads 1 Pair 119-1441 procedures you perform oxygen to the patient may • Review and modify crash cart inventory as required by be the difference between the anesthesia and medical staff at your facility a life saved and • Document necessary approvals for inventory list and Suction a life lost. 449-0032 emergency management protocols by your Medical Executive Committee and Governing Board The Vario 18 is a medical suction pump, offering dependability, low • Establish protocols for emergency response and noise and mobility.