MPLAB C30 C Compiler User's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

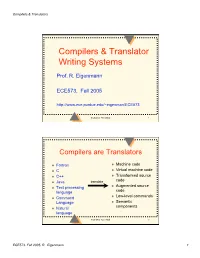

Compilers & Translator Writing Systems

Compilers & Translators Compilers & Translator Writing Systems Prof. R. Eigenmann ECE573, Fall 2005 http://www.ece.purdue.edu/~eigenman/ECE573 ECE573, Fall 2005 1 Compilers are Translators Fortran Machine code C Virtual machine code C++ Transformed source code Java translate Augmented source Text processing language code Low-level commands Command Language Semantic components Natural language ECE573, Fall 2005 2 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 1 Compilers & Translators Compilers are Increasingly Important Specification languages Increasingly high level user interfaces for ↑ specifying a computer problem/solution High-level languages ↑ Assembly languages The compiler is the translator between these two diverging ends Non-pipelined processors Pipelined processors Increasingly complex machines Speculative processors Worldwide “Grid” ECE573, Fall 2005 3 Assembly code and Assemblers assembly machine Compiler code Assembler code Assemblers are often used at the compiler back-end. Assemblers are low-level translators. They are machine-specific, and perform mostly 1:1 translation between mnemonics and machine code, except: – symbolic names for storage locations • program locations (branch, subroutine calls) • variable names – macros ECE573, Fall 2005 4 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 2 Compilers & Translators Interpreters “Execute” the source language directly. Interpreters directly produce the result of a computation, whereas compilers produce executable code that can produce this result. Each language construct executes by invoking a subroutine of the interpreter, rather than a machine instruction. Examples of interpreters? ECE573, Fall 2005 5 Properties of Interpreters “execution” is immediate elaborate error checking is possible bookkeeping is possible. E.g. for garbage collection can change program on-the-fly. E.g., switch libraries, dynamic change of data types machine independence. -

Source-To-Source Translation and Software Engineering

Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 2013, 6, 30-40 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jsea.2013.64A005 Published Online April 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jsea) Source-to-Source Translation and Software Engineering David A. Plaisted Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, USA. Email: [email protected] Received February 5th, 2013; revised March 7th, 2013; accepted March 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 David A. Plaisted. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Source-to-source translation of programs from one high level language to another has been shown to be an effective aid to programming in many cases. By the use of this approach, it is sometimes possible to produce software more cheaply and reliably. However, the full potential of this technique has not yet been realized. It is proposed to make source- to-source translation more effective by the use of abstract languages, which are imperative languages with a simple syntax and semantics that facilitate their translation into many different languages. By the use of such abstract lan- guages and by translating only often-used fragments of programs rather than whole programs, the need to avoid writing the same program or algorithm over and over again in different languages can be reduced. It is further proposed that programmers be encouraged to write often-used algorithms and program fragments in such abstract languages. Libraries of such abstract programs and program fragments can then be constructed, and programmers can be encouraged to make use of such libraries by translating their abstract programs into application languages and adding code to join things together when coding in various application languages. -

Datatypes (Pdf Format)

Basic Scripting, Syntax, and Data Types in Python Mteor 227 – Fall 2020 Basic Shell Scripting/Programming with Python • Shell: a user interface for access to an operating system’s services. – The outer layer between the user and the operating system. • The first line in your program needs to be: #!/usr/bin/python • This line tells the computer what python interpreter to use. Comments • Comments in Python are indicated with a pound sign, #. • Any text following a # and the end of the line is ignored by the interpreter. • For multiple-line comments, a # must be used at the beginning of each line. Continuation Line • The \ character at the end of a line of Python code signifies that the next line is a continuation of the current line. Variable Names and Assignments • Valid characters for variable, function, module, and object names are any letter or number. The underscore character can also be used. • Numbers cannot be used as the first character. • The underscore should not be used as either the first or last character, unless you know what you are doing. – There are special rules concerning leading and trailing underscore characters. Variable Names and Assignments • Python is case sensitive! Capitalization matters. – The variable f is not the same as the variable F. • Python supports parallel assignment >>> a, b = 5, 'hi' >>> a 5 >>> b 'hi' Data Types • Examples of data types are integers, floating-point numbers, complex numbers, strings, etc. • Python uses dynamic typing, which means that the variable type is determined by its input. – The same variable name can be used as an integer at one point, and then if a string is assigned to it, it then becomes a string or character variable. -

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy

The LLVM Instruction Set and Compilation Strategy Chris Lattner Vikram Adve University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign lattner,vadve ¡ @cs.uiuc.edu Abstract This document introduces the LLVM compiler infrastructure and instruction set, a simple approach that enables sophisticated code transformations at link time, runtime, and in the field. It is a pragmatic approach to compilation, interfering with programmers and tools as little as possible, while still retaining extensive high-level information from source-level compilers for later stages of an application’s lifetime. We describe the LLVM instruction set, the design of the LLVM system, and some of its key components. 1 Introduction Modern programming languages and software practices aim to support more reliable, flexible, and powerful software applications, increase programmer productivity, and provide higher level semantic information to the compiler. Un- fortunately, traditional approaches to compilation either fail to extract sufficient performance from the program (by not using interprocedural analysis or profile information) or interfere with the build process substantially (by requiring build scripts to be modified for either profiling or interprocedural optimization). Furthermore, they do not support optimization either at runtime or after an application has been installed at an end-user’s site, when the most relevant information about actual usage patterns would be available. The LLVM Compilation Strategy is designed to enable effective multi-stage optimization (at compile-time, link-time, runtime, and offline) and more effective profile-driven optimization, and to do so without changes to the traditional build process or programmer intervention. LLVM (Low Level Virtual Machine) is a compilation strategy that uses a low-level virtual instruction set with rich type information as a common code representation for all phases of compilation. -

Tdb: a Source-Level Debugger for Dynamically Translated Programs

Tdb: A Source-level Debugger for Dynamically Translated Programs Naveen Kumar†, Bruce R. Childers†, and Mary Lou Soffa‡ †Department of Computer Science ‡Department of Computer Science University of Pittsburgh University of Virginia Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260 Charlottesville, Virginia 22904 {naveen, childers}@cs.pitt.edu [email protected] Abstract single stepping through program execution, watching for par- ticular conditions and requests to add and remove breakpoints. Debugging techniques have evolved over the years in response In order to respond, the debugger has to map the values and to changes in programming languages, implementation tech- statements that the user expects using the source program niques, and user needs. A new type of implementation vehicle viewpoint, to the actual values and locations of the statements for software has emerged that, once again, requires new as found in the executable program. debugging techniques. Software dynamic translation (SDT) As programming languages have evolved, new debugging has received much attention due to compelling applications of techniques have been developed. For example, checkpointing the technology, including software security checking, binary and time stamping techniques have been developed for lan- translation, and dynamic optimization. Using SDT, program guages with concurrent constructs [6,19,30]. The pervasive code changes dynamically, and thus, debugging techniques use of code optimizations to improve performance has necessi- developed for statically generated code cannot be used to tated techniques that can respond to queries even though the debug these applications. In this paper, we describe a new optimization may have changed the number of statement debug architecture for applications executing with SDT sys- instances and the order of execution [15,25,29]. -

The Interplay of Compile-Time and Run-Time Options for Performance Prediction Luc Lesoil, Mathieu Acher, Xhevahire Tërnava, Arnaud Blouin, Jean-Marc Jézéquel

The Interplay of Compile-time and Run-time Options for Performance Prediction Luc Lesoil, Mathieu Acher, Xhevahire Tërnava, Arnaud Blouin, Jean-Marc Jézéquel To cite this version: Luc Lesoil, Mathieu Acher, Xhevahire Tërnava, Arnaud Blouin, Jean-Marc Jézéquel. The Interplay of Compile-time and Run-time Options for Performance Prediction. SPLC 2021 - 25th ACM Inter- national Systems and Software Product Line Conference - Volume A, Sep 2021, Leicester, United Kingdom. pp.1-12, 10.1145/3461001.3471149. hal-03286127 HAL Id: hal-03286127 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03286127 Submitted on 15 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Interplay of Compile-time and Run-time Options for Performance Prediction Luc Lesoil, Mathieu Acher, Xhevahire Tërnava, Arnaud Blouin, Jean-Marc Jézéquel Univ Rennes, INSA Rennes, CNRS, Inria, IRISA Rennes, France [email protected] ABSTRACT Both compile-time and run-time options can be configured to reach Many software projects are configurable through compile-time op- specific functional and performance goals. tions (e.g., using ./configure) and also through run-time options (e.g., Existing studies consider either compile-time or run-time op- command-line parameters, fed to the software at execution time). -

Virtual Machine Part II: Program Control

Virtual Machine Part II: Program Control Building a Modern Computer From First Principles www.nand2tetris.org Elements of Computing Systems, Nisan & Schocken, MIT Press, www.nand2tetris.org , Chapter 8: Virtual Machine, Part II slide 1 Where we are at: Human Abstract design Software abstract interface Thought Chapters 9, 12 hierarchy H.L. Language Compiler & abstract interface Chapters 10 - 11 Operating Sys. Virtual VM Translator abstract interface Machine Chapters 7 - 8 Assembly Language Assembler Chapter 6 abstract interface Computer Machine Architecture abstract interface Language Chapters 4 - 5 Hardware Gate Logic abstract interface Platform Chapters 1 - 3 Electrical Chips & Engineering Hardware Physics hierarchy Logic Gates Elements of Computing Systems, Nisan & Schocken, MIT Press, www.nand2tetris.org , Chapter 8: Virtual Machine, Part II slide 2 The big picture Some . Some Other . Jack language language language Chapters Some Jack compiler Some Other 9-13 compiler compiler Implemented in VM language Projects 7-8 VM implementation VM imp. VM imp. VM over the Hack Chapters over CISC over RISC emulator platforms platforms platform 7-8 A Java-based emulator CISC RISC is included in the course written in Hack software suite machine machine . a high-level machine language language language language Chapters . 1-6 CISC RISC other digital platforms, each equipped Any Hack machine machine with its VM implementation computer computer Elements of Computing Systems, Nisan & Schocken, MIT Press, www.nand2tetris.org , Chapter 8: Virtual Machine, -

Design and Implementation of Generics for the .NET Common Language Runtime

Design and Implementation of Generics for the .NET Common Language Runtime Andrew Kennedy Don Syme Microsoft Research, Cambridge, U.K. fakeÒÒ¸d×ÝÑeg@ÑicÖÓ×ÓfغcÓÑ Abstract cally through an interface definition language, or IDL) that is nec- essary for language interoperation. The Microsoft .NET Common Language Runtime provides a This paper describes the design and implementation of support shared type system, intermediate language and dynamic execution for parametric polymorphism in the CLR. In its initial release, the environment for the implementation and inter-operation of multiple CLR has no support for polymorphism, an omission shared by the source languages. In this paper we extend it with direct support for JVM. Of course, it is always possible to “compile away” polymor- parametric polymorphism (also known as generics), describing the phism by translation, as has been demonstrated in a number of ex- design through examples written in an extended version of the C# tensions to Java [14, 4, 6, 13, 2, 16] that require no change to the programming language, and explaining aspects of implementation JVM, and in compilers for polymorphic languages that target the by reference to a prototype extension to the runtime. JVM or CLR (MLj [3], Haskell, Eiffel, Mercury). However, such Our design is very expressive, supporting parameterized types, systems inevitably suffer drawbacks of some kind, whether through polymorphic static, instance and virtual methods, “F-bounded” source language restrictions (disallowing primitive type instanti- type parameters, instantiation at pointer and value types, polymor- ations to enable a simple erasure-based translation, as in GJ and phic recursion, and exact run-time types. -

A Brief History of Just-In-Time Compilation

A Brief History of Just-In-Time JOHN AYCOCK University of Calgary Software systems have been using “just-in-time” compilation (JIT) techniques since the 1960s. Broadly, JIT compilation includes any translation performed dynamically, after a program has started execution. We examine the motivation behind JIT compilation and constraints imposed on JIT compilation systems, and present a classification scheme for such systems. This classification emerges as we survey forty years of JIT work, from 1960–2000. Categories and Subject Descriptors: D.3.4 [Programming Languages]: Processors; K.2 [History of Computing]: Software General Terms: Languages, Performance Additional Key Words and Phrases: Just-in-time compilation, dynamic compilation 1. INTRODUCTION into a form that is executable on a target platform. Those who cannot remember the past are con- What is translated? The scope and na- demned to repeat it. ture of programming languages that re- George Santayana, 1863–1952 [Bartlett 1992] quire translation into executable form covers a wide spectrum. Traditional pro- This oft-quoted line is all too applicable gramming languages like Ada, C, and in computer science. Ideas are generated, Java are included, as well as little lan- explored, set aside—only to be reinvented guages [Bentley 1988] such as regular years later. Such is the case with what expressions. is now called “just-in-time” (JIT) or dy- Traditionally, there are two approaches namic compilation, which refers to trans- to translation: compilation and interpreta- lation that occurs after a program begins tion. Compilation translates one language execution. into another—C to assembly language, for Strictly speaking, JIT compilation sys- example—with the implication that the tems (“JIT systems” for short) are com- translated form will be more amenable pletely unnecessary. -

MPLAB C Compiler for PIC24 Mcus and Dspic Dscs User's Guide

MPLAB® C Compiler for PIC24 MCUs and dsPIC® DSCs User’s Guide 2002-2011 Microchip Technology Inc. DS51284K Note the following details of the code protection feature on Microchip devices: • Microchip products meet the specification contained in their particular Microchip Data Sheet. • Microchip believes that its family of products is one of the most secure families of its kind on the market today, when used in the intended manner and under normal conditions. • There are dishonest and possibly illegal methods used to breach the code protection feature. All of these methods, to our knowledge, require using the Microchip products in a manner outside the operating specifications contained in Microchip’s Data Sheets. Most likely, the person doing so is engaged in theft of intellectual property. • Microchip is willing to work with the customer who is concerned about the integrity of their code. • Neither Microchip nor any other semiconductor manufacturer can guarantee the security of their code. Code protection does not mean that we are guaranteeing the product as “unbreakable.” Code protection is constantly evolving. We at Microchip are committed to continuously improving the code protection features of our products. Attempts to break Microchip’s code protection feature may be a violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. If such acts allow unauthorized access to your software or other copyrighted work, you may have a right to sue for relief under that Act. Information contained in this publication regarding device Trademarks applications and the like is provided only for your convenience The Microchip name and logo, the Microchip logo, dsPIC, and may be superseded by updates. -

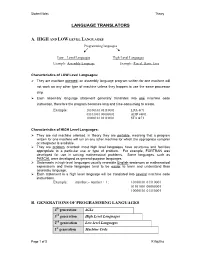

Language Translators

Student Notes Theory LANGUAGE TRANSLATORS A. HIGH AND LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES Programming languages Low – Level Languages High-Level Languages Example: Assembly Language Example: Pascal, Basic, Java Characteristics of LOW Level Languages: They are machine oriented : an assembly language program written for one machine will not work on any other type of machine unless they happen to use the same processor chip. Each assembly language statement generally translates into one machine code instruction, therefore the program becomes long and time-consuming to create. Example: 10100101 01110001 LDA &71 01101001 00000001 ADD #&01 10000101 01110001 STA &71 Characteristics of HIGH Level Languages: They are not machine oriented: in theory they are portable , meaning that a program written for one machine will run on any other machine for which the appropriate compiler or interpreter is available. They are problem oriented: most high level languages have structures and facilities appropriate to a particular use or type of problem. For example, FORTRAN was developed for use in solving mathematical problems. Some languages, such as PASCAL were developed as general-purpose languages. Statements in high-level languages usually resemble English sentences or mathematical expressions and these languages tend to be easier to learn and understand than assembly language. Each statement in a high level language will be translated into several machine code instructions. Example: number:= number + 1; 10100101 01110001 01101001 00000001 10000101 01110001 B. GENERATIONS OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES 4th generation 4GLs 3rd generation High Level Languages 2nd generation Low-level Languages 1st generation Machine Code Page 1 of 5 K Aquilina Student Notes Theory 1. MACHINE LANGUAGE – 1ST GENERATION In the early days of computer programming all programs had to be written in machine code. -

Adding Self-Healing Capabilities to the Common Language Runtime

Adding Self-healing capabilities to the Common Language Runtime Rean Griffith Gail Kaiser Columbia University Columbia University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract systems can leverage to maintain high system availability is to perform repairs in a degraded mode of operation[23, 10]. Self-healing systems require that repair mechanisms are Conceptually, a self-managing system is composed of available to resolve problems that arise while the system ex- four (4) key capabilities [12]; Monitoring to collect data ecutes. Managed execution environments such as the Com- about its execution and operating environment, performing mon Language Runtime (CLR) and Java Virtual Machine Analysis over the data collected from monitoring, Planning (JVM) provide a number of application services (applica- an appropriate course of action and Executing the plan. tion isolation, security sandboxing, garbage collection and Each of the four functions participating in the Monitor- structured exception handling) which are geared primar- Analyze-Plan-Execute (MAPE) loop consumes and pro- ily at making managed applications more robust. How- duces knowledgewhich is integral to the correct functioning ever, none of these services directly enables applications of the system. Over its execution lifetime the system builds to perform repairs or consistency checks of their compo- and refines a knowledge-base of its behavior and environ- nents. From a design and implementation standpoint, the ment. Information in the knowledge-base could include preferred way to enable repair in a self-healing system is patterns of resource utilization and a “scorecard” tracking to use an externalized repair/adaptation architecture rather the success of applying specific repair actions to detected or than hardwiring adaptation logic inside the system where it predicted problems.