Leases, Land and Local Leaders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HCAR CDC LIST AS on MARCH 21, 2018 Sr No Member Folio Parid

HCAR CDC LIST AS ON MARCH 21, 2018 Sr No Member Folio ParID CDC A/C # SHARE HOLDER'S NAME ADDRESS 1 CDC-1 00208 30 ALFA ADHI SECURITIES (PVT) LTD. SUITE NO. 303, 3RD FLOOR, MUHAMMAD BIN QASIM ROAD, I.I. CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI 2 CDC-2 00208 3075 Rafiq III-F, 13/7, NAZIMABAD NO. 3, 74600 KARACHI 3 CDC-3 00208 3729 Omar Farooq HOUSE NO B-144, BLOCK-3, GULISTAN-E-JOUHAR KARACHI 4 CDC-4 00208 7753 AFSHAN SHAKIL A-82, S.B.C.H.S. BLOCK 12, GULISTAN-E-JAUHAR KARACHI 5 CDC-5 00208 8827 SARWAR DIN L-361, SHEERIN JINNAH COLONY , CLIFTON KARACHI 6 CDC-6 00208 11805 SHUNIL KUMAR OFFICE # 105,HUSSAIN TRADE CENTER, ALTAF HUSSAIN ROAD, NEW CHALI KARACHI 7 CDC-7 00208 12126 ABDUL SAMAD D-9, DAWOOD COLONY, SHARFABAD, NEAR T.V. STATION. KARACHI 8 CDC-8 00208 18206 Syeda Sharmeen Flat # 506, Ana Classic Apartment, Ghulam Hussain Qasim Road, Garden West KARACHI 9 CDC-9 00208 18305 Saima Asif FLAT NO: 306, MOTIWALA APARTMENT, PLOT NO: BR 5/16, MULJI STREET, KHARADHAR KARACHI 10 CDC-10 00208 18511 Farida FLAT NO: 306, MOTIWALA APARTMENT, PLOT NO: BR 5/16, MULJI STREET, KHARADHAR, KARACHI 11 CDC-11 00208 19626 MANOHAR LAL MANOHAR EYE CLINIC JACOBABAD 12 CDC-12 00208 21945 ADNAN FLAT NO 101, PLOT NO 329, SIDRA APPARTMENT, GARDEN EAST, BRITTO ROAD, KARACHI 13 CDC-13 00208 25672 TAYYAB IQBAL FLAT NO. 301, QASR-E-GUL, NEAR T.V. STATION, JAMAL-UD-DIN AFGHANI ROAD, SHARFABAD KARACHI 14 CDC-14 00208 26357 MUHAMMAD SALEEM KHAN G 26\9,LIAQUAT SQUARE, MALIR COLONY, KARACHI 15 CDC-15 00208 27165 SABEEN IRFAN 401,HEAVEN PRIDE,BLOCK-D, FATIMA JINNAH COLONY,JAMSHED ROAD#2, KARACHI 16 CDC-16 00208 27967 SANA UL HAQ 3-F-18-4, NAZIMABAD KARACHI 17 CDC-17 00208 29112 KHALID FAREED SONIA SQUARE, FLAT # 05, STADIUM ROAD, CHANDNI CHOWK, KARACHI 5 KARACHI 18 CDC-18 00208 29369 MOHAMMAD ZEESHAN AHMED FLAT NO A-401, 4TH FLOOR, M.L GARDEN PLOT NO, 690, JAMSHED QUARTERS, KARACHI 19 CDC-19 00208 30151 SANIYA MUHAMMAD RIZWAN HOUSE # 4, PLOT # 3, STREET# 02, MUSLIMABAD, NEAR DAWOOD ENGG. -

A Case Study of Begum Nasim Wali Khan

WOMEN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP IN TRADITIONAL ASIAN SOCIETIES: A CASE STUDY OF BEGUM NASIM WALI KHAN BY HASSINA BASHIR DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR SESSION: 2011 – 2012 1 WOMEN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP IN TRADITIONAL ASIAN SOCIETIES: A CASE STUDY OF BEGUM NASIM WALI KHAN Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR SEPTEMBER, 2019 2 ABSTRACT In traditional Asian societies, women still face impediments in different fields of their lives including politics. Such hurdles obstruct them to attain top political leadership positions. Despite these obstacles, Asian societies have experienced some notable women political leaders, who not only acquired political leadership positions but sustained these positions successfully for extended period of time. Likewise, the rise of a woman political leader, Nasim Wali Khan in a traditional Pukhtun society is an intriguing matter to explore. Various theoretical studies contest how political leaders emerge and sustain their positions. These theoretical explanations shift their focus from factors such as personal traits, situations, charisma and skills. However, this study extensively borrows from theories based on premises that situation and skills matter most when it comes to attainment or retainment of political leadership. This research is based on primary data gathered from a variety of respondents through semi-structured interviews, along with analysis of selected speeches; this research explores the course to political leadership followed by Nasim Wali Khan. The existing literature proposes that Asian women political leaders acquire leadership position because of the support of their illustrious families and political exigency. -

Unclaimed2006 (PKR)

ANNEXURE - A FORM - XI (PKR) THE BANKING COMPANIES ORDINANCE, 1962 - FORM-XI (RETURN OF UNCLAIMED ACCOUNTS IN PAKISTAN WHICH HAVE NOT BEEN OPERATED UPON FOR 10 YEARS OR MORE AS ON THE DATE OF THE RETURN) AS ON 31-12-2006 NATIONAL BANK OF PAKISTAN MR. IMTIAZ AHMED SIDDIQUI, SECTIONAL HEAD/O.G-I, UNCLAIMED SECTION, EBD&TD, NBP, HO, KARACHI DATE OF LAST BR - NAME OF OFFICES OR BRANCH OF BALANCE NATURE OF ACCOUNT REASON, IF ANY, WHY NOT PROVINCE NAME OF THE DEPOSITORS ADDRESS OF THE DEPOSITORS (WHETHER CURRENT, DEPOSIT OR REMARKS CODE THE BANKING COMPANY OPERATED UPON OUTSTANDING SAVING, FIXED OR OTHER) WITHDRAWAL 1 243 5 6 7 SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. ZA SIDDIQI KARACHI 500.00 O 427494 31-Dec-1996 PO PO NBP MAIN BR KHI SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. JAFFAR BROS 52 SADDAR TALPUR RD KHI 3,216.00 O 318451 31-Dec-1996 PO NBP MAIN BR KHI SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. YASIR TEXTILE MILLS 71 SITE KARACHI 603.82 C 95396 27-Feb-1986 N/R NBP MAIN BR KHI C AC SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. RAEES MARVI HERBAL CO KARACHI 158.09 C 95387 27-Feb-1986 NBP MAIN BR KHI C/AC SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. MAJEED KARACHI 387.50 C 95314 27-Feb-1986 NBP MAIN BR KHI C/AC SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. FICOM GARMENTS 52 SITE KARACHI 480.00 C 95298 27-Feb-1986 NA NBP MAIN BR KHI C/AC SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. NAFEES AHMED KARACHI 4,618.05 C 95289 27-Feb-1986 ADD DIFFER C/AC NBP MAIN BR KHI SINDH 2 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI. -

Bus Routes Karachi January 2010

Bus Routes Karachi January 2010 Route #: 1-A Stops: Faqir Colony, Metroville, Bawany Ghali, Valika Mill, Habbib Bank, Petrol Pump, Lasbela, Sabilwali Masjid, Old Exhibition, Sadar, Frere Road, Burns Road, Bandar Road, Tower Route #: 1-B Stops: Nazimabd, Bara Maidan, Lasbela, Lawrence Road, Barness Street, Bandar Road, Tower Route #: 1-C Stops: M.P.R Colony, Qasba Colony, Banaras Colony, Pathan Colony, S.I.T.E, Habib Bank, Bismillah Hotel, Gandhi Garden, Garden Road, Plaza, Regal, Shahra-e-Liaquat, National Museum, Tower, Sultanabad Route #: 1-D Stops: Ittehad Town, Torri Chowk Sector II, Orangi Township, Banaras Colony, Pathan Colony, Petrol Pump, Liaquatabad No. 10, Liaquatabad, Post Office, Teen Hatti, Jehangir Road, Empress Market, Cantt Station Route #: 1-F Stops: Naval Colony, Mauripur, Gulbai Chowk, Tower, Juna Market, Ramswami, Garden Bara Board, Valika, Orangi Township No. 10 Route #: 1-G Stops: M.W Tower, Frere Road, Sadar, Numaish, Goro Mandir, Teen Hatti, Liaquat No. 10, Petrol Pump, Nazimabad No. 2, Gandhi Chowk, Paposh Nagar, Abdullah College, Metro Cinema, Data Chowk Orangi Town Route #: 1-H Stops: Gulshan-e-Bahar, Orangi Sector No. 14, Orangi Sector No. 13, Orangi Sector No. 7, Orangi Sector No. 5, Qadafi Chowk, Qasba Mour, Banaras Colony, Valika Hospital, Valika Mill, Habib Bank, S.I.T.E, Post Office, Maroon Mill, Laltain Factory, Ghani Chowk, Shershah, Miran Naka, Chakiwara, Lee Market, Kharadar, Jamat Khana, Tower Route #: 1-K Stops: Tower, Regal Cinema, Plaza, Garden, Pakistan Quarters, Bara Board, Banaras, Qasba Mour, -

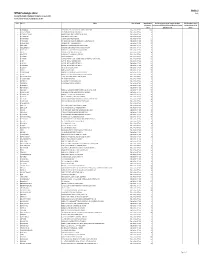

Detail of Unclaimed Dividend As at 30-06-2020

Annexure - A NETSOL Technologies Limited (Part-I) Investor Wise Details of Unclaimed Dividend as at June 30, 2020. For the Period From June 30, 2008 to June 30, 2017 Sr No Name (s) Address Nature of Amount Amount to which Due Date for transfer into the Companies Unclaimed Other Information as may be each person is Instruments and Dividend and Insurance Benefits and Investor considered relevant for the entitled Education Account purpose 1 MR. IRFAN MUSTAFA 233- WIL SHINE BULEVARD,, SUITE NO.930, SANTA MONIKA, CALIFORNIA 90401. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 109,981 2 MR. SHAHID JAVED BURKI 11112 STACKHOUSE CT POTOMAC,, MD 20854, U.S.A. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 81 3 MR. EDWARD ALLEN HOLMES HOMINGTON DOWN, SALISBURY,, WILTSHIRE, ENGLAND, SP5 4NW Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 757 4 MR. EUGEN BECKERT GUNDEITWEG, 1075365 CALW,, GERMANY. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 757 5 MR, NISHAT HUSSAIN C-5 SHADAB COLONY, TIMPLE ROAD LAHORE. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 547 6 MR. OWAIS QASSIM 67/3, KARACHI MEMON,, CO.OPERATIVE HOUSING SOCIETY, ALAMGIR ROAD, KARACHI. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 547 7 MR. WALEED FAROOQ 638-W BLOCK PHAS 111,, D.H.A, LAHORE PAKISTAN. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 547 8 SHAHID HAMEED HOUSE NO 210 7/10 MANWABAD, NEAR MADINA MASJID NAWABSHAH Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 71 9 SHAKEEL AHMED MALIK BUDHAL SHAH COLONY NEAR, MADINA MASJID MANWABAD NAWABSHAH. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 71 10 NIAMAT-UL-LAH HOUSE NO 153-TAJ COLONY, NEAR GIRLS SCHOOL NAWAB SHAH. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 71 11 UZMA ADIL C/O MAJOR ADIL 89 ORDANACE UNIT, SIALKOT CANTT. -

Ccwr-2000-2001.Pdf

i Citizens’ Report of the Citizens’ Campaign for Women’s Representation in Local Government in Pakistan 2000-2001 Aurat Publication and Information Service Foundation ii This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. iii Contents The Beginning of the Beginning v Acknowledgements 8 Contributors 9 Glossary 10 1. Voting, Supporting, Agitating 13 2. Looking for the Women Out There 17 3. The Foundation and the Lifeline 23 4. Chipping Away at Centuries of Resistance 37 5. Political Rivalries Allow Space for Women Candidates 65 6. Mobilising the Women and Standing by Those Who Dared 73 7. DCCs Lead by Example 95 8. Checking Rejection of Women Candidates 101 9. The Hotline Between State and Citizens 109 10. Knowledge is Power 121 11. Reaching Out to the Women Out There 129 12. Citizens’ Organisations Interact with Political Parties 139 13. Preparation to Move into the Political Arena 149 14. A Citizen’s Movement Comes of Age 157 Appendices 163 A. National Steering Committee of CCWR 165 B. Provincial Advisory Committees of CCWR 166 C. Aurat Foundation Staff Participating in CCWR 169 D. Government Officials Participating in CCWR 172 E. District Coordinators and Joint Coordinators of CCWR 174 F. CCWR Support Organisations by Province and District 177 G. Electoral Results of Candidates on Women’s Reserved Seats 223 H. Map of Women’s Seats Filled by Province and District 224 iv The Beginning of the Beginning The very discreet entry of about 36,000 women into the jealously guarded domain for public representatives transpired in a dramatic way through direct elections to union councils. -

Standard Chartered Bank (Pakistan) Limited

STANDARD CHARTERED BANK (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE CNIC # ARE NOT AVAILABLE-23MAR16 DIVIDEND ISSUE # D-10 FOR THE FINAL DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31-DEC-15 Folio/ CDS S. No. Security Holder Name Address No. of Shares Gross Dividend CNIC Status No 1 15 A GHAFFAR 14 HANIF TERRECE JAFFAR, FADOO ROAD KHARADAR, KARACHI. 280 350 MISSING 2 16 A GHAFFAR SIDDIQUI 5-E 2/1, NEW KARACHI KARACHI. 1,945 2,431 MISSING 3 17 A KARIM R NO 10 4TH FLOOR SIRAJ MANSION EMBANHMENT RD KARACHI 60 75 MISSING 4 18 A QADIR C/O ZENY ENTERPRISES, SHAMA PLAZA, BLOCK A1, SHOP NO. A1-2, G. ALLAN ROAD, KHARADAR, 335 419 MISSING KARACHI. 5 19 A RASHEED A-10 AL FAZAL BLK B N NAZ,KARACHI. 352 440 MISSING 6 20 A RASHID GALI NO-17, GUL MOHD LANE LYARI,KARACHI. 335 419 MISSING 7 21 A.K.M.HAMDANI 603-SAIMA GARDEN, 167-H BLOCK 3, P.E.C.H.S., KHALID BIN WALID ROAD, KARACHI. 1,090 1,363 MISSING 8 23 DR. A.SATTAR 160 B S.M.C.H.S. KARACHI 1,732 2,165 MISSING 9 24 A.WAHID GULSHER AFZAL PHARMCY ADAMJEE DAWOOD ROAD KARACHI. 5,225 6,531 MISSING 10 25 MR. A. FAHEEM KHAN 1-A, SHADMAN ARCADE TARIQ ROAD P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 317 396 MISSING 11 26 A.GHAFFAR C/O NO.18 DHEDHI CENTER NEW NAHAM ROAD KARACHI-2. 145 181 MISSING 12 27 A. JABBAR C/O AQUEEL KARIM DHEDHI ROOM NO. -

Cibrary IRC Internationalvvater and Sanitation Centre Tel.: .-31 70 20 669 80 Fax: +31 70 35 899 64

822 PKOROO ORANGT PILOT PROJECT Institutions and Programs 84th QUARTERLY REPORT OCT, NOV., DEC 2000 Participants of the First Dr Akhtar Hameed Khan Memorial Forum held on 10th October 2000 in Karachi -Cibrary IRC InternationalVvater and Sanitation Centre Tel.: .-31 70 20 669 80 Fax: +31 70 35 899 64 ORANGI PILOT P ROJECT PLOT NO. SI-4, SECTOR 5/A, QASBA COLONY MANfiHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI-75800 PHONE NOS. 6652297 6658021 ORANGI PILOT PROJECT - Institutions and Programs Contents: Pages I. Introduction: 1-2 II. Receipts and Expenditure-Audited figure (1980 to 2000) 3 (OPP and OPP society) III. Receipts and Expenditure (2000-2001) Abstract of institutions 4 IV. Orangl Pilot Project - Research and Training Institute (OPP-RTI) 5-53 V. OPP-KHASDA Health and Family Planning Programme (KHASDA) 54-68 VI. Orangi Charitable Trust: Micro Enterprise Credit (OCT) 69-92 VII. Rural Development Trust (RDT) 93-100 •I. INTRODUCTION: 1. Since April 1980 the following programs have evolved: Low Cost Sanitation-started in 1981 * Low Cost Housing-started in 1988 Health & Family Planning-started in 1985 Women Entrepreneurs-started in 1984 Family Enterprise-started in 1987 Education- started in 1987 stopped in 1990. New program started in 1996. Social Forestry- started in 1990 stopped in 1997 Rural Development-started in 1992 2. The programs are autonomous with their own registered institutions, separate budgets, accounts and audits. The following independent institutions are now operating : i. OPP Society Council: It receives funds from INFAQ Foundation and distributes the funds according to the budgets to the OCT, OPP-RTI Khasda and RDT . For details of distribution see page 4. -

Exploring Karachi's Transport System Problems

Exploring Karachi’s transport system problems A diversity of stakeholder perspectives Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban Keywords: March 2016 urban development, transport, Karachi About the authors Acknowledgements Mansoor Raza Email: [email protected] I would like to thank freelance researcher and surveyor Humayun Waqas for identifying key informants and for Mansoor Raza is a freelance researcher and a visiting faculty organising the interviews. I am immensely grateful to the member at Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science respondents who shared their precious time and useful insights. and Technology (SZABIST). He is an electrical engineer turned I am indebted to Faisal Imran, a freelance photographer, environmentalist, and has been involved with civil Society for providing photos, and to freelance writer Asifya Aziz for and NGOs since 1995. He worked as disaster manager in converting the raw data from the interviews into case studies. Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Pakistan in Afghanistan Emergency I am also grateful to Younus Baloch, director of the Urban 2002, Tsunami 2004, Kashmir Earthquake -2005 and IDP Resource Centre in Karachi, who was gracious enough to share crisis in 2009. Mansoor also works as a researcher with Arif his views quite often on the subject. Hasan and Associates since 1998 on diverse urban issues. He has researched and published widely and has a special interest Above all, l would like to show my gratitude to the noted in the amendment and repeal of discriminatory laws and their architect, urban planner, sociologist and mentor Arif Hasan misuse in Pakistan. Mansoor blogs at https://mansooraza. of Arif Hasan and Associates for sharing his wisdom with me wordpress.com during the course of this research. -

Shareholders List for Contestants

SR.NO. FOLIO NO. NAME ADDRESS 1 1 HONDA MOTOR COMPANY LTD. NO 1-1, 2 CHOME MINAMI AOYAMA MINATO - KU, TOKYO - 107, JAPAN. 2 3 MR. AAMIR H SHIRAZI C/O SHIRAZI INVESTMENTS (PVT.) LIMITED 2ND FLOOR, FEDERATION HOUSE, SHARAE FIRDOUSI, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 3 4 MR. SAQUIB H. SHIRAZI HOUSE NO.2, STREET NO.15, KHAYABAN-E-BADBAN, DEFENCE HOUSING SOCIETY KARACHI 4 51 MR. AKIRA MURAYAMA HONDA MOTOR COMPANY LIMITED NO. 1-1, 2 CHOME MINAMI AOYAMA, MANATO-KU, TOKYO-107, JAPAN 5 52 MR. HIRONOBU YOSHIMURA HONDA MOTOR COMPANY LIMITED NO. 1-1, 2 CHOME MINAMI AOYAMA, MANATO-KU, TOKYO-107, JAPAN 6 54 MS. RIE MIHARA MAKOTOYA PAKISTAN (PVT.) LIMITED, SHOP NO.132,THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK-9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMO, CLIFTON, KARACHI 7 55 MR. KAZUNORI SHIBAYAMA HONDA MOTOR COMPANY LIMITED NO. 1-1, 2 CHOME MINAMI AOYAMA, MANATO-KU, TOKYO-107, JAPAN 8 56 MR. KATSUMI KASAI HONDA MOTOR COMPANY LIMITED NO. 1-1, 2 CHOME MINAMI AOYAMA, MANATO-KU, TOKYO-107, JAPAN 9 208 MRS. SHAMSAH RAHEEM DHANANI FLAT NO.203, FALCON CENTRE, BEHIND SONERI BANK LIMITED, BLOCK-7, CLIFTON, KARACHI 10 225 SH KAMRAN SHAHZAM MAGOON E-30, PHASE II, KDA, FLAT NO 3, NORTH KARACHI 11 235 MISS NAIMA C/O MR. KAMAL UD DIN, R-790, BLOCK 17, FEDERAL B AREA, KARACHI 38 12 247 ALTAF KHAN HOUSE # 500, SECTOR 15-C ORANGI TOWN KARACHI 13 252 MRS SAEEDA KHATOON C/O S M UMER,A-64, REHMAN VILLAS, SECTOR 22 SCHEME 33,NEAR SHAKIL GARDEN, KARACHI 14 254 MANSOOR AHMED A-480, BLOCK J, NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 15 264 MUHAMMAD NAWAZ L 564, SECTOR 5C/3, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI 16 281 MRS GULSHAN, 10 EBRAHIM MANSION, ADAMJEE BUDHA BHOY ROAD, THATHAI COMPOUND, KARACHI 17 305 GHULAM RASOOL C/O ALLIED BANK LTD., JODIA BAZAR BR., P.O. -

VU Prospectus

V i r t u a l U n i v e r s i t y World Class Education at Your Doorstep akistan - Prospectus 2016-17 Virtual University of P y t i s r e v i n U l a u t r i V Prospectus 2016-17 Virtual University of Pakistan Address: M.A.Jinnah Campus, Defence Road, Off Raiwind Road, Lahore. UAN: 042-111-880-880 | 0304-111-0880 | Fax: 042-99202174 E-mail: [email protected] | [email protected] | Web: www.vu.edu.pk Price / VirtualUniversityOfPakistan | / VUPakistan Rs. 500/- www.vu.edu.pk Mission Statement WELCOME TO “to provide exible & affordable world-class education to everyone at doorsteps” V i r t u a l U n i v e r s i t y VIRTUAL UNIVERSITY The information provided in this prospectus is relevant to academic year 2016-17 OF PAKISTAN and meant for the guidance of prospective students of Virtual University of Pakistan and shall not be deemed to constitute a contract between the University or any third party. While compiling the information, every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy, correctness and completeness. However, it shall not imply any legal binding or liability on part of the University or its employees in any way. w w w . v u . e d u . p k The University reserves the right to change the provisions of this prospectus at any time, including, but not limited to, admission eligibility criteria, degree requirements, course offerings and fees schedule etc. as necessitated by University or legislative action. -

Final List of Electoral Rolls of Registered Graduates As Members University Senate Under Section 22(1)(Xvi) of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur Act 1975 Uni

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Final list of Electoral Rolls of Registered Graduates as members University Senate under section 22(1)(xvi) of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur Act 1975 Uni. Which Sr. # Name Father's Name Exam. Passed Registration No. Address Graduated H. # B-III/619 Govt. Girls High School, Street, Mohallah Qazina, 1 Abdul Haq Yar Muhammad B.Sc PU LHR Rahimyar Khan 2 Abdul hadi Khwaja M. M. Ramzan B.A PU LHR 36/10 Riaz Colony Bahawalpur 3 Abdus Samad Ahmad Abdul Wahid B.A IUB Al-Hafeez Manzil Mohallah Bagh Mahi Bahawalpur 4 Abdul hadi Khwaja Allah Bakhsh B.A PU LHR Principal Govt. Inter College Yazman 5 Azra Naseem Akhtar Abdul Rehman B.A IUB H. # 393/C Satellite Town Bahawalpur Qureshi Street, Opposite Dubai Mahal College, St. No.6, H.No.B-X- 6 Ejaz Ahmad Qureshi Hafiz Faiz Ahmad B.A IUB 128/4, Saddiq Colony, Bahawalpur 7 Abdul Majeed Kausar Qadir Bakhsh Bhatti B.A IUB Bahawalpur Arts Council Bahawalpur 8 Abdul Karim Arshad R. Rahim Bakhsh B.A PU LHR zulfiqar St. Colony Haji Mohad Khan, RYK 9 Abdul Qayyum Shahid Abdul Latif B.A IUB 775/C Satellite Town Bahawalpur 10 Abida Kalsoom Qazi Baqa Mohammad B.A IUB Mohalah Qazian Rahimyar Khan 11 Abdul Rauf Abdul Latif B.A IUB 775/C Sattelite Town Bahawalpur 12 Arif Tanveer Ch. Ghulam Ali B.A PU LHR 37-B, Model Town, B, Bahawalpur 13 Amtul Rehman Abdul Aziz B.A IUB C/O Head Master Govt. Tameer -e- Millat H/S Sadiq Abad 14 Miss Alia Batool Abdul Qadir B.A IUB Mashood Iqbal Advocate Mohallah Chah Fatha Khan Bahawalpur 15 Abid Hussain Shah S.