Western Classical Music Strand 1: Baroque Solo Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

Symphony 04.22.14

College of Fine Arts presents the UNLV Symphony Orchestra Taras Krysa, music director and conductor Micah Holt, trumpet Erin Vander Wyst, clarinet Jeremy Russo, cello PROGRAM Oskar Böhme Concerto in F Minor (1870–1938) Allegro Moderato Adagio religioso… Allegretto Rondo (Allegro scherzando) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Rondo: Allegro Edward Elgar Cello Concerto, Op. 85 (1857–1934) Adagio Lento Adagio Allegro Tuesday, April 22, 2014 7:30 p.m. Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall Performing Arts Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES The Concerto in F minor Composed 1899 Instrumentation solo trumpet, flute, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, four horns, trumpet, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Oskar Bohme was a trumpet player and composer who began his career in Germany during the late 1800’s. After playing in small orchestras around Germany he moved to St. Petersburg to become a cornetist for the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra. Bohme composed and published is Trumpet Concerto in E Minor in 1899 while living in St. Petersburg. History caught up with Oskar Bohme in 1934 when he was exiled to Orenburg during Stalin’s Great Terror. It is known that Bohme taught at a music school in the Ural Mountain region for a time, however, the exact time and circumstances of Bohme’s death are unknown. Bohme’s Concerto in F Minor is distinguished because it is the only known concerto written for trumpet during the Romantic period. The concerto was originally written in the key of E minor and played on an A trumpet. -

MUSIC in the BAROQUE 12 13 14 15

From Chapter 5 (Baroque) MUSIC in the BAROQUE (c1600-1750) 1600 1650 1700 1720 1750 VIVALDI PURCELL The Four Seasons Featured Dido and Aeneas (concerto) MONTEVERDI HANDEL COMPOSERS L'Orfeo (opera) and Messiah (opera) (oratorio) WORKS CORELLI Trio Sonatas J.S. BACH Cantata No. 140 "Little" Fugue in G minor Other Basso Continuo Rise of Instrumental Music Concepts Aria Violin family developed in Italy; Recitative Orchestra begins to develop BAROQUE VOCAL GENRES BAROQUE INSTRUMENTAL GENRES Secular CONCERTO Important OPERA (Solo Concerto & Concerto Grosso) GENRES Sacred SONATA ORATORIO (Trio Sonata) CANTATA SUITE MASS and MOTET (Keyboard Suite & Orchestral Suite) MULTI-MOVEMENT Forms based on opposition Contrapuntal Forms FORMS DESIGNS RITORNELLO CANON and FUGUE based on opposition BINARY STYLE The Baroque style is characterized by an intense interest in DRAMATIC CONTRAST TRAITS and expression, greater COUNTRAPUNTAL complexity, and the RISE OF INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. Forms Commonly Used in Baroque Music • Binary Form: A vs B • Ritornello Form: TUTTI • SOLO • TUTTI • SOLO • TUTTI (etc) Opera "Tu sei morta" from L'Orfeo Trio Sonata Trio Sonata in D major, Op. 3, No. 2 1607 by Claudio MONTEVERDI (1567–1643) Music Guide 1689 by Arcangelo CORELLI (1653–1713) Music Guide Monteverdi—the first great composer of the TEXT/TRANSLATION: A diagram of the basic imitative texture of the 4th movement: Baroque, is primarily known for his early opera 12 14 (canonic imitation) L'Orfeo. This work is based on the tragic Greek myth Tu sei morta, sé morta mia vita, Violin 1 ed io respiro; of Orpheus—a mortal shepherd with a god-like singing (etc.) Tu sé da me partita, sé da me partita Violin 2 voice. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

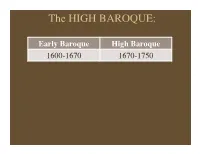

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Citymac 2018

CityMac 2018 City, University of London, 5–7 July 2018 Sponsored by the Society for Music Analysis and Blackwell Wiley Organiser: Dr Shay Loya Programme and Abstracts SMA If you are using this booklet electronically, click on the session you want to get to for that session’s abstract. Like the SMA on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SocietyforMusicAnalysis Follow the SMA on Twitter: @SocMusAnalysis Conference Hashtag: #CityMAC Thursday, 5 July 2018 09.00 – 10.00 Registration (College reception with refreshments in Great Hall, Level 1) 10.00 – 10.30 Welcome (Performance Space); continued by 10.30 – 12.30 Panel: What is the Future of Music Analysis in Ethnomusicology? Discussant: Bryon Dueck Chloë Alaghband-Zadeh (Loughborough University), Joe Browning (University of Oxford), Sue Miller (Leeds Beckett University), Laudan Nooshin (City, University of London), Lara Pearson (Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetic) 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch (Great Hall, Level 1) 14.00 – 15.30 Session 1 Session 1a: Analysing Regional Transculturation (PS) Chair: Richard Widdess . Luis Gimenez Amoros (University of the Western Cape): Social mobility and mobilization of Shona music in Southern Rhodesia and Zimbabwe . Behrang Nikaeen (Independent): Ashiq Music in Iran and its relationship with Popular Music: A Preliminary Report . George Pioustin: Constructing the ‘Indigenous Music’: An Analysis of the Music of the Syrian Christians of Malabar Post Vernacularization Session 1b: Exploring Musical Theories (AG08) Chair: Kenneth Smith . Barry Mitchell (Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance): Do the ideas in André Pogoriloffsky's The Music of the Temporalists have any practical application? . John Muniz (University of Arizona): ‘The ear alone must judge’: Harmonic Meta-Theory in Weber’s Versuch . -

Unwrap the Music Concerts with Commentary

UNWRAP THE MUSIC CONCERTS WITH COMMENTARY UNWRAP VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS – SUMMER AND WINTER Eugenie Middleton and Peter Thomas UNWRAP THE MUSIC VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS SUMMER AND WINTER INTRODUCTION & INDEX This unit aims to provide teachers with an easily usable interactive resource which supports the APO Film “Unwrap the Music: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons – Summer and Winter”. There are a range of activities which will see students gain understanding of the music of Vivaldi, orchestral music and how music is composed. It provides activities suitable for primary, intermediate and secondary school-aged students. BACKGROUND INFORMATION CREATIVE TASKS 2. Vivaldi – The Composer 40. Art Tasks 3. The Baroque Era 45. Creating Music and Movement Inspired by the Sonnets 5. Sonnets – Music Inspired by Words 47. 'Cuckoo' from Summer Xylophone Arrangement 48. 'Largo' from Winter Xylophone Arrangement ACTIVITIES 10. Vivaldi Listening Guide ASSESSMENTS 21. Transcript of Film 50. Level One Musical Knowledge Recall Assessment 25. Baroque Concerto 57. Level Two Musical Knowledge Motif Task 28. Programme Music 59. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task 31. Basso Continuo 64. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task – 32. Improvisation Examples of Student Answers 33. Contrasts 69. Level Three Musical Knowledge Analysis Task 34. Circle of Fifths 71. Level Three Context Questions 35. Ritornello Form 36. Relationship of Rhythm 37. Wordfind 38. Terminology Task 1 ANTONIO VIVALDI The Composer Antonio Vivaldi was born and lived in Italy a musical education and the most talented stayed from 1678 – 1741. and became members of the institution’s renowned He was a Baroque composer and violinist. -

(1756-1791) Completed Wind Concertos: Baroque and Classical Designs in the Rondos of the Final Movements

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's (1756-1791) Completed Wind Concertos: Baroque and Classical Designs in the Rondos of the Final Movements Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Koner, Karen Michelle Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:25:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193304 1 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s (1756-1791) Completed Wind Concertos: Baroque and Classical Designs in the Rondos of the Final Movements By Karen Koner __________________________________ Copyright © Karen Koner 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music In the Graduate College The University of Arizona 2008 2 STATEMENT BY THE AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. Signed: Karen Koner Approval By Thesis Director This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: J. Timothy Kolosick 4/30/2008 Dr. -

Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, Op

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2009-11-24 Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, Op. 27 by Paul Wranitzky: A Critical Edition Sharon Meilstrup Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Meilstrup, Sharon, "Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, Op. 27 by Paul Wranitzky: A Critical Edition" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 2309. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2309 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 27 BY PAUL WRANITZKY: A CRITICAL EDITION by Sharon Meilstrup A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Music Brigham Young University December 2009 Copyright © 2009 Sharon Meilstrup All Rights Reserved BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Sharon Meilstrup This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. ____________________________ _________________________________ Date E. Harrison Powley, Chair ____________________________ _________________________________ Date Steven -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

J. S. Bach and the Two Cultures of Musical Form*

Understanding Bach, 10, 109–122 © Bach Network UK 2015 J. S. Bach and the Two Cultures of Musical Form* GERGELY FAZEKAS Leopold Godowsky, the celebrated pianist of the first decades of the twentieth century, left the USA for a tour of the Far East in 1923.1 During the lengthy boat journeys between different stops on the concert tour, he prepared virtuoso transcriptions of Bach’s Cello Suites and Violin Solos, principally because he needed ‘warm-up’ opening pieces for his concerts. On 12 March, travelling from Java to Hong Kong aboard the passenger steamboat SS Tjikembang, he finished his version of the Sarabande of the C-minor cello suite, which he dedicated to Pablo Casals (Example 1). The original piece is in binary form, characteristic of eighteenth-century dance suites. The first part modulates from C minor to the relative E-flat major; the second part finds its way back from E-flat major to the tonic after a short detour in F minor. In Bach’s composition, the first part consists of eight bars, the second twelve bars. In Godowsky’s transcription, however, the second part is extended by four additional bars. From bar 17, the first four bars of the piece return note for note. Accordingly, the form becomes three-part in a symmetric arrangement: the first eight bars that modulate from tonic to the relative major are followed by eight bars that modulate from the relative major to the fourth degree, and these are followed by another eight bars of the return of the beginning. When the transcriptions were published by Carl Fischer in New York in 1924, Godowsky gave the following explanation as to why he changed Bach’s form: On several occasions I have been tempted to slightly modify the architectural design in order to give the structural outline a more harmonious form. -

The Rise and Fall of the Cellist-Composer of the Nineteenth Century

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Rise and Fall of the Cellist- Composer of the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Study of the Life and Works of Georg Goltermann Including A Complete Catalog of His Cello Compositions Katherine Ann Geeseman Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CELLIST-COMPOSER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE LIFE AND WORKS OF GEORG GOLTERMANN INCLUDING A COMPLETE CATALOG OF HIS CELLO COMPOSITIONS By KATHERINE ANN GEESEMAN A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Katherine Geeeseman defended this treatise on October 20th, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Gregory Sauer Professor Directing Treatise Evan Jones University Representative Alexander Jiménez Committee Member Corinne Stillwell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my dad iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This treatise would not have been possible without the gracious support of my family, colleagues and professors. I would like to thank Gregory Sauer for his support as a teacher and mentor over our many years working together. I would also like to thank Dr. Alexander Jiménez for his faith, encouragement and guidance. Without the support of these professors and others such as Dr.