Government Assited and Market-Driven Land Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WB. 2005. Gender Issues and Best

Gender Issues and Best Practices in Land Administration Projects A Synthesis Report June 2005 Prepared for Gender and Rural Development Thematic Group (PREM/ARD) and the Land Policy and Administration Thematic Group (ARD) of The World Bank Table of Contents Acknowledgments v Acronyms vii Executive summary ix •Why does gender matter in land projects? ix • Priority gender issues in land administration projects x 1. Introduction 1 2. Why does gender matter for land policy? Theory and evidence 3 • Gendered economic and social benefits of land rights 3 •Regional challenges to gender equity in land policy 5 3. Actors in the struggle to improve women’s land rights 11 • State institutions 11 • Labor organizations 12 •Legal aid organizations 13 • Customary institutions 13 •Women’s organizations 14 • Donor organizations 14 4. Priority gender issues in land administration projects 17 • Intrahousehold legal and customary rights 19 • Identification of property holders 26 • Methodology for gender-disaggregated field assessment of land rights 31 • Adjudication and registration processes 32 • Education, training, and communication 35 iii 5. Lessons learned and recommendations 41 •Legal foundation 41 • Identification of property right holders 42 • Research 42 • Adjudication and registration processes 43 • Education, training, and communication 44 Appendix 1: Summaries of country case studies 47 Appendix 2: Case study methodologies 55 Appendix 3: Sample template for gender-specific baseline social 57 assessment Appendix 4: Sample gender-specific indicators -

Torrens Title in North Carolina - Maybe a Hundred Years Is Long Enough John V

Campbell Law Review Volume 39 Article 3 Issue 2 Spring 2017 2017 Torrens Title in North Carolina - Maybe a Hundred Years Is Long Enough John V. Orth Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Recommended Citation John V. Orth, Torrens Title in North Carolina - Maybe a Hundred Years Is Long Enough, 39 Campbell L. Rev. 271 (2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Orth: Torrens Title in North Carolina - Maybe a Hundred Years Is Long E Torrens Title in North Carolina-Maybe a Hundred Years Is Long Enough JOHN V. ORTH* For over a century, North Carolina property owners have been offered an alternative to the traditionaldeed and recordingsystem. Title to land may instead be entered in the Torrens system of registered titles. Under the Torrens system, the court determines the state of the title and issues a certificate, which is held in the registry with a copy given to the registered owner. The certificate provides conclusive evidence of ownership and of any liens or encumbrances on the property. Unlike titles evidenced by deeds, Torrens titles are not subject to loss by adverse possession, and transfer of a Torrens title is a simple process of changing the certificate in the registry and issuing a new certificate. A darling of Progressive law reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, nineteen states eventually adopted the Torrens system, although many later had second thoughts and abandonedthe system. -

Comparison of Deeds Registration and Title Registration

LC Paper No. CB(1)1357/02-03(02) Bills Committee on Land Titles Bill Comparison of Deeds Registration and Title Registration Introduction This paper provides: (a) a table comparing the main features of the current deeds registration system with those of the proposed title registration system; and (b) an outline of the proposed arrangements for parallel running of the two systems. Comparison 2. A table setting out the features of the current deeds registration system and the title registration system proposed under the Land Titles Bill is at the Annex. Parallel Running 3. While there will be two pieces of legislation governing land registration after enactment of the Land Titles Bill, we plan to have only one single administrative system to handle all registrations. Submission of deeds under the Land Registration Ordinance and applications for registration - 2 - under the Land Titles Ordinance will both be made to the same customer service centre of the Land Registry. Each set of documents will then be handled by the Land Registry as required by the ordinance under which it is submitted. 4. There will be a single computerized information system handling all properties irrespective of which ordinance they are registered under. The system will be set up to show clearly which ordinance each particular property is registered under and to provide the supporting information and documents required by that ordinance. The system will serve both the Land Registry and external customers. Internally it will guide Land Registry staff through the correct registration procedures applicable to the property. Externally it will give searchers up to date information on the status of each property. -

A Hybrid System of Land Titles and Deeds Registration As a New Model for Zambia: a Case Study of the Lands and Deeds Registry Lusaka

A hybrid system of Land Titles and Deeds registration as a new model for Zambia: A case study of the Lands and Deeds Registry Lusaka. By Fatima Mandhu Study Leader: Prof. Dr. J. Malan Thesis submitted on 31st October 2014 in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Law of University of Africa Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Zulekha Kassam Mandhu, who at the age of ninety- five still remains an inspiration for me. ii Acknowledgement Firstly, I would like to extend special thanks to my study leader, Dr. Kobus Malan without whose constant guidance, cooperation and valuable contribution, this research work would have not been completed. You are not only a great study leader but also a great friend. Secondly, my special thank goes to my family especially my Mum who at the age of ninety- five has an answer for every question and has inspired me to find answers for the research questions posed in this study. Thirdly, I would like to thank the partners and staff of the Law Firm, Solly Patel Hamir and Lawrence who assisted me with the documents, files and information needed to complete the primary research presented in chapter four of the study. Fourthly, no amount of thanking would be sufficient to express my gratitude to the staff at the Lands and Deeds Registry whose cooperation in the collection of data made it possible for me to develop the proposed land recordation and registration model for Zambia. Lastly and most importantly, I shall always be indebted to Mr Kwei Aatta Sakyi whose careful editing and checking of the study has produced a perfect piece of work. -

Lands and Deeds Registry Act

The Laws of Zambia REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA THE LANDS AND DEEDS REGISTRY ACT CHAPTER 185 OF THE LAWS OF ZAMBIA CHAPTER 185 THE LANDS AND DEEDS REGISTRY ACT THE LANDS AND DEEDS REGISTRY ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation PART II REGISTRATION OF DOCUMENTS Copyright Ministry of Legal Affairs, Government of the Republic of Zambia The Laws of Zambia 3. Establishment and constitution of Registry of Deeds 4. Documents required to be registered 5. Times within which registration must be effected 6. Documents to be void for want of registration 7. Priority of documents and date of registration 8. Optional registration of documents not required to be registered 9. Registers to be kept 10. Miscellaneous Register, contents of 11. Correction of errors or omissions in Registers 12. Documents to refer to diagram, plan or description 13. Identity of person presenting document for registration 14. Registrar to be satisfied that all duties have been paid 15. Registration of notarially certified copies 16. Details of registration 17. Copies to be filed consecutively 18. Memorandum of registration to be endorsed on original 19. Evasion of duty by understatement of consideration 20. Translations, if not in English language 21. Registration not to cure defects 22. Registry open for search 23. Official certificates of search 24. Indemnity to officers of Registry 25. Admissibility in evidence of certified copies 26. Procedure to be adopted when certified copy is tendered in evidence 27. Application of Bills of Sale Acts 28. Concessions by chiefs unaffected PART III PROVISIONAL CERTIFICATES AND CERTIFICATES OF TITLE Copyright Ministry of Legal Affairs, Government of the Republic of Zambia The Laws of Zambia 29. -

Guidelines on Legal Elements for European Land Register Information

7th Annual Publication GUIDELINES ON LEGAL ELEMENTS FOR LAND REGISTER INFORMATION IN EUROPE Jorge López Summary I. A structure for the registry information II. The part of information related to properties 1. The connecting factor 2. The description of the property 2.1. Descriptions in the ownership title and spatial data 2.2. The description of the properties in land registers: an attempt to find a minimum common denominator 2.3. More criteria for purposes of identification or description III. The part of information related to owners 1. Approach to proprietorship 2. Elements of information on ownership IV. The part of information related to mortgages and encumbrances 1. Kinds of encumbrances 2. Rank or preference between charges V. Other relevant aspects References 1 7th Annual Publication One of the results of IMOLA project is a lot of material on legal aspects of land registration across Europe. The Contact Points of ELRN have made interesting contributions explaining their models and systems. This is an important background, valuable for the mutual understanding in this scope, and can be used and studied to try to understand the complex European situation regarding land registration, from the legal point of view. The aim of this article is to present relevant legal aspects to consider laying down some guidelines for exchanging land register information at a European level, especially considering what the main targets should be: judicial cooperation and conveyancing. I. A structure for the registry information ABC structure for land register information In several Land Register systems of Europe there are practices which allow us to find some commonalities in legal aspects on land register information, as well as what structure may be adequate to deliver the system across Europe for the mentioned purposes of judicial cooperation and conveyancing. -

Registration Form for Paper Submissionsopens in New Window

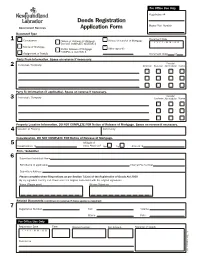

PAGE 3 OF 4 Instructions for completing the Registration Application Form The Registration Application Form (RAF) is in a type‐able PDF format. If you choose to hand‐write in the information on the form please ensure that it is printed and is legible. SECTION 1 Document type: Select the box next to the document type to indicate the type of document that you are registering. If you select OTHER, you MUST specify the document type. Document Date: This is the date of the execution or drafting of the document that is recorded on the document. If you do not have a document date then leave the field blank. Please Note: (i) When registering a Notice of Mortgage, you must attach a legible written description and affidavit of value, if applicable. You may attach supporting affidavits. • Do not attach the mortgage document, schedules, promissory notes or terms and conditions. (Note: Submitters other than law firms and pre‐authorized filers may be asked by the Registry to attach the full mortgage document.) (ii) When registering a Notice of Release of Mortgage please attach the Release of Mortgage document. (Note: Law firms and other pre‐authorized filers do not attach the Release of Mortgage document.) • Do not complete sections 4 and 5 of the registration application form. • You must complete section 7 which references the document being released. (iii) When registering a Partial Release of Mortgage you must attach the document. • You must Complete Section 4 SECTION 2 Party From Information: Party from includes: mortgagors, vendors, releasors, guarantors and confirmors. Enter the name of the individual or corporation exactly as it appears on the document, this includes middle names and initials. -

Land in the Caribbean

Caribbean Land Policy Network LAND IN THE CARIBBEAN ISSUES OF POLICY, ADMINISTRATION AND MANAGEMENT IN THE ENGLISH- SPEAKING CARIBBEAN Edited by Dr. Allan N. Williams LAND IN THE CARIBBEAN PROCEEDINGS OF A WORKSHOP ON LAND POLICY, ADMINISTRATION AND MANAGEMENT IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING CARIBBEAN Edited by Allan Williams Email: [email protected] Special thanks to Jane Dennis for the final editing of this manuscript. All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this book are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or co-operating institutions. Verbatim copying of any part of this book is permitted, in any medium, provided that the copier gives a complete citation of the title, chapter, author and editor of the book, and provided that all copies made remain under these same terms and conditions which are conspicuously published on all copies. Hard copies of this book can be acquired from: Terra Institute 10900 Stanfield Road Blue Mounds, Wisconsin 53517 Email: [email protected] For further information about the Caribbean Land Policy Network, check the web site: www.terrainstitute.org or contact Caribbean Land Policy Network Steering Committee: Chairperson: Andrew Bishop, Commissioner of Land, Guyana (592) 227-2582 (ph) (592) 226-4052 (fx) [email protected] Secretary: Allan N. Williams (868) 624-2142 (ph) [email protected] Manuscript was prepared from digitised copy at the Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, for publication, October 2003. -

Development of Land-Title Registration Systems

Development of Land−Title Registration Systems − A Developed Country Experience Australia Table of Contents Development of Land−Title Registration Systems − A Developed Country Experience Australia............1 FOREWORD..........................................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................3 I. NEW SOUTH WALES BEGINNINGS..................................................................................................4 A. Allocation of land.........................................................................................................................5 B. Registration of deeds...................................................................................................................5 Sources............................................................................................................................................6 II. THE SYSTEM OF SURVEYS.............................................................................................................6 A. The functions of the system.........................................................................................................6 B. Creation of parcels by the Crown................................................................................................6 -

Study on Key Aspects of Land Registration and Cadastral Legislation Part 1 of 2

Study on Key Aspects of Land R on Key Study Study on Key Aspects of Land Registration and Cadastral Legislation Part 1 of 2 egistration and Cadastral Legislationegistration 1 Part Sponsored, printed and published by: HM Land Registry 32 Lincoln’s Inn Fields LONDON WC2A 3PH United Kingdom Tel (++44) 020 7917 8888 ext. 4505 On behalf of: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Human Settlements Working Party on Land Administration Palais des Nations Printed and published on behalf of UNECE Working Party on 8-10 Avenue de la Paix 1211 GENEVA Land Administration by Her Majesty’s Land Registry London Switzerland May 2000 Tel (++41) 22 917 2374 CONTENTS OF THIS STUDY REPORT PART 1 Page Preface 3 A list of the 36 Countries (and 43 jurisdictions) responding to the questionnaire 5 Topics covered in the study and the Key definitions 7 A commentary on the results of the study 9 Snapshots from country responses Graphic summaries of key questions 35 Contact addresses of those responding 37 Contact addresses of UNECE WPLA Bureau officials 45 Annex 1 Indicating country answers categorised by individual question 47 PART 2 Annex 2 Indicating answers categorised by country 1 2 PREFACE The Working Party on Land Administration (the former Meeting of Officials on Land Administration) of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN-ECE) decided to prepare a study on key aspects of land registration and cadastral legislation in the ECE countries, as part of its programme of work for 1999-2002 (HBP/WP.7/1999/2, Annex IV). Following representations made by member states UNECE identified the need to assist in this area by identifying actual legislative practice. -

Torrens System Vs General Law System of Title Summary

Torrens System vs General Law System of Title Summary Deeds Registration System: - Old system – established a centralised register with the specific aim of recording instruments or dealings over old title land. Aim: - Reduce the risk that a purchaser might acquire an interest in land without knowledge of an earlier inconsistent interest. Old Title Land: - Does not come within the application of the Torrens system because it was issued by the Crown prior to the introduction of the Torrens system and it has been converted to Torrens title land. o To verify ownership, it is necessary to trace, in a complete and unbroken chain, all the land transactions which have affected the land since the time of the initial Crown grant. The relevant rule for determining the quality of a vendor’s title was “nemo dat non quod habit” [one cannot give what one does not have]. Thus, any defect in the vendor’s title meant the purchaser would acquire only a defective title – or, if any of the instruments in the chain of deeds was void for any reason, the purchaser would obtain no title at all. This meant that general law title was derivative and historical – each owner’s title in the chain depended on every former owner having had good title and every instrument of conveyance having been valid and enforceable. Chain includes all deeds creating interests in the land along the way Deeds of conveyance: vendor to purchaser Deeds of mortgage: mortgagor to mortgagee Deeds of reconveyance: mortgagee to mortgagor Deeds of grant (easements covenant etc) Deeds -

The Deeds Registration Act 1868

This PUBLIC BILL originated i* the LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL md having titis d(W passed as now printed is transmitted to the HOUSE OF ]REPRESENTATIVES JOr their concu,v·ence. Legislative Cotmcil Chamber, 24th September, 1868. A BILL INTITULED AN AcT to consolidate and amend the Laws relating to Title. the Registration of Deeds affecting Real Property. HERE,AS it is expedient to consolidate and amend the laws Preamble. relating to the Registration of Deeds and other instruments affecting real property BE IT THEREFORE ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand 5 in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows- 1. The Short Title of this Act shall be " The Deeds Registration Short Title. Act 1868." 2. The Ordinances and Acts specified in Schedule A. to this Act Repeol. save the parts excepted in the said Schedule are hereby respectively 10 repealed Provided always that everything which shall have happened been done perfected or been made valid under or by virtue of the said Acts respectively shall be and the same is hereby declared to be as good valid and effectual to all intents and purposes as if this Act had not been passed. 15 3. In the construction of this Act the word "land" sliall extend to Interpretatio.. any estate or interest whatever in real property over which the Native title is extinguished and the word " instrument " shall extend to any Crown grant deed contract will codicil exemplification or certified copy of will probate testamentary order certificate power of attorney 20 affidavit memorandum notice memorial or other document either written or printed or partly written and partly printed affecting any land within the Colony authorized to be registered by this Act or by any law which now is or hereafter may be in force relating to registration of documents affecting real property.