A Comparative Framing Analysis of ISIL in the Online Coverage of CNN and Al-Jazeera Talal Alshathry Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018 THE TRAVELERS American Jihadists in Syria and Iraq BY Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Cliford Program on Extremism February 2018 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2018 by Program on Extremism Program on Extremism 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 www.extremism.gwu.edu Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................v A Note from the Director .........................................................................................vii Foreword ......................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary .......................................................................................................1 Introduction: American Jihadist Travelers ..........................................................5 Foreign Fighters and Travelers to Transnational Conflicts: Incentives, Motivations, and Destinations ............................................................. 5 American Jihadist Travelers: 1980-2011 ..................................................................... 6 How Do American Jihadist -

U.S. Citizens Kidnapped by the Islamic State John W

CRS Insights U.S. Citizens Kidnapped by the Islamic State John W. Rollins, Specialist in Terrorism and National Security ([email protected], 7-5529) Liana Rosen, Specialist in International Crime and Narcotics ([email protected], 7-6177) February 13, 2015 (IN10167) Overview On February 10, 2015, President Barack Obama acknowledged that U.S. citizen Kayla Mueller was killed while held in captivity by the terrorist group known as the Islamic State (IS). This was the fourth death of an American taken hostage by the Islamic State: Abdul-Rahman Kassig (previously Peter Kassig), James Foley, and Steven Sotloff were also killed. The death of Mueller and the graphic videos depicting the deaths of the other three Americans have generated debate about the U.S. government's role and capabilities for freeing hostages. In light of these deaths, some policymakers have called for a reevaluation of U.S. policy on international kidnapping responses. Questions include whether it is effective and properly coordinated and implemented, should be abandoned or modified to allow for exceptions and flexibility, or could benefit from enhancements to improve global adherence. Scope The killing of U.S. citizens by the Islamic State may be driven by a variety of underlying motives. Reports describe the group as inclined toward graphic and public forms of violence for purposes of intimidation and recruitment. It is unclear whether the Islamic State would have released its Americans hostages in exchange for ransom payments or other concessions. Foley's family, for example, disclosed that the Islamic State demanded a ransom of 100 million euros ($132 million). -

Why Concessions Should Not Be Made to Terrorist Kidnappers

European Journal of Political Economy 44 (2016) 41–52 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Political Economy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejpe Why concessions should not be made to terrorist kidnappers Patrick T. Brandt, Justin George, Todd Sandler ⁎ School of Economic, Political & Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA article info abstract Article history: This paper examines the dynamic implications of making concessions to terrorist kidnappers. Received 21 December 2015 We apply a Bayesian Poisson changepoint model to kidnapping incidents associated with Received in revised form 23 May 2016 three cohorts of countries that differ in their frequency of granting concessions. Depending Accepted 24 May 2016 on the cohort of countries during 2001–2013, terrorist negotiation successes encouraged 64% Available online 26 May 2016 to 87% more kidnappings. Our findings also hold for 1978–2013, during which these negotia- tion successes encouraged 26% to 57% more kidnappings. Deterrent aspects of terrorist casual- Keywords: ties are also quantified; the dominance of religious fundamentalist terrorists meant that such Kidnappings casualties generally did not curb kidnappings. Changepoints © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY- Game theory Concessions NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Violent ends Dynamic analysis “…we know that hostage takers looking for ransoms distinguish between those governments that pay ransoms and those that do not, and make a point of not taking hostages from those countries that do not pay.” David S. Cohen, US Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, 2012 speech to ChathamHouse [Callimachi (2014a)] 1. -

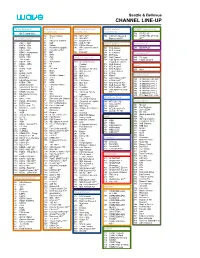

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

An Al-Jazeera Effect in the US? a Review of the Evidence

Review Article Global Media Journal 2017 ISSN 1550-7521 Vol.15 No.29:83 An Al-Jazeera Effect in the US? A Tal Samuel-Azran* Review of the Evidence Sammy Ofer School of Communications, The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, 1 Kanfe Nesharin Street, Herzliya 46150, Israel Abstract *Corresponding author: Tal Samuel-Azran Some scholars argue that following 9/11Al Jazeera has promoted an Arab perspective of events in the US by exporting its news materials to the US news market. The study examines the validity of the argument through a review of the [email protected] literature on the issue during three successive periods of US-Al Jazeera interactions: (a) Al Jazeera Arabic's re-presentation in US mainstream media following 9/11, Sammy Ofer School of Communications, specifically during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (b) Al Jazeera English television The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, 1 Kanfe Nesharin Street, Herzliya 46150, channel’s attempts to enter the US market since 2006 and (c) the reception of Israel. Al Jazeera America in the US, where the paper also adds an original analysis of Al Jazeera America's Twitter followers profiles. Together, these analyses provides Tel: 972 9-952-7272 strong counterevidence to the argument that Al-Jazeera was able to promote an Arab perspective of events in the US as the US administration, media and public resisted its entry to the US market. Citation: Samuel-Azran T. An Al-Jazeera Keywords: Al Jazeera; Qatar; Counter-public; Intercultural communication; United Effect in the US? A Review of the States; Twitter Evidence. -

TITLE Ll—AUTHORITY for the USE of MILITARY FORCE AGAINST

DAV15E09 S.L.C. AMENDMENT NO.llll Calendar No.lll Purpose: To authorize the use of the United States Armed Forces against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES—114th Cong., 1st Sess. (no.) lllllll (title) llllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Referred to the Committee on llllllllll and ordered to be printed Ordered to lie on the table and to be printed AMENDMENT intended to be proposed by Mr. KAINE (for himself and Mr. FLAKE) Viz: 1 At the appropriate place, insert the following: 2 TITLE ll—AUTHORITY FOR 3 THE USE OF MILITARY FORCE 4 AGAINST THE ISLAMIC STATE 5 OF IRAQ AND THE LEVANT 6 SEC. l1. SHORT TITLE. 7 This title may be cited as the ‘‘Authority for the Use 8 of Military Force Against the Islamic State of Iraq and 9 the Levant Act’’. 10 SEC. l2. FINDINGS. 11 Congress makes the following findings: DAV15E09 S.L.C. 2 1 (1) The terrorist organization that has referred 2 to itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant 3 and various other names (in this resolution referred 4 to as ‘‘ISIL’’) poses a grave threat to the people and 5 territorial integrity of Iraq and Syria, regional sta- 6 bility, and the national security interests of the 7 United States and its allies and partners. 8 (2) ISIL holds significant territory in Iraq and 9 Syria and has stated its intention to seize more ter- 10 ritory and demonstrated the capability to do so. 11 (3) ISIL leaders have stated that they intend to 12 conduct terrorist attacks internationally, including 13 against the United States, its citizens, and interests. -

After Foley Killing, US Defends Refusal to Pay Ransom To

The Obama administration sharply defended its refusal to negotiate with or pay ransom to terrorist groups that kidnap, following the videotaped execution this week of American photojournalist James Foley by the Islamic State. “We believe that paying ransoms or making concessions would put all Americans overseas at greater risk” and would provide funding for groups whose capabilities “we are trying to degrade,” Marie Harf, a State Department spokeswoman, said in a briefing Thursday. Harf said it is illegal for any American citizen to pay ransom to a group, such as the Islamic State, that the U.S. government has designated as a terrorist organization. ADVERTISING In late 2013, more than a year after Foley was captured while reporting on Syria’s civil war, his family received several e-mails from the Islamic State, including one demanding 100 million Euros, about $133 million, for his freedom, according to GlobalPost, Foley’s employer. The amount, many times the ransom demanded for other Western hostages, indicated that the Islamic State was not serious about releasing Foley, U.S. officials said. His family and GlobalPost agreed, said Richard Byrne, the company’s vice president and director of communications. “I don’t think there was a negotiation,” he said. GlobalPost has said that it shared with federal officials all communications it received from the kidnappers, including a final e-mail last week saying they were about to execute Foley. Earlier this summer, U.S. Special Operations forces had tried to rescue Foley and three other Americans known to be held by the Islamic State. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel on Thursday described the raid — in which one U.S. -

Gw Extremism Tracker Terrorism in the United States

GW EXTREMISM TRACKER TERRORISM IN THE UNITED STATES INDIVIDUALS HAVE BEEN CHARGED IN THE U.S. ON OFFENSES RELATED 217 to the Islamic State (also known as IS, ISIS, and ISIL) since March 2014, when the first arrests occurred. Of those: Their activities were located in 30 states and the District of Columbia the average age of are male 90% 28 those charged. have pleaded or * the average length 157 were found guilty 13.2 of sentence in years. *Uses 470 months for life sentences per the practice of the U.S. Sentencing Commission were accused of attempting 39% to travel or successfully traveled abroad. were accused of being 31% involved in plots to carry out attacks on U.S. soil. were charged in an operation MALE 58% involving an informant and/or an undercover agent. FEMALE indicates law enforcement operation Acknowledgement Disclaimer This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as under Grant Award Number 20STTPC00001‐01 necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Apprehensions & Charges for Other conspirators were involved in the IS “hostage-taking scheme,” which resulted in the kidnapping and subsequent death of Jihadist Groups James Foley, Kayla Mueller, Steven Sotloff, Peter Kassig, as well as British and Japanese nationals. The pair, who also face material support charges, were captured in January of 2018 by OCT 21 VA the Syrian Democratic Forces and transferred to American custody in 2019. -

Syria's Future and the War Against ISIS

14 October 2014 Syria's Future and the War against ISIS How will the military campaign against ISIS affect Syria over the long-term? Murhaf Jouejati warns that unless Washington actively trains, equips and politically accommodates ‘moderate’ Syrian opposition forces, the greatest beneficiary of the intervention could indeed be the Assad regime. By Murhaf Jouejati for ISN On 10 September 2014, US President Barack Obama publicly declared war on ISIS with the goal of degrading and destroying the extremist organization. Obama’s new stance was an escalation of his earlier, more limited decision to use American airpower against ISIS in western Iraq. In his televised speech, Obama affirmed that he would not hesitate to strike at ISIS targets in Syria as well – without seeking the Assad regime’s authorization. What explains the shift from Obama’s earlier “hands off” approach towards Syria, and how will the new approach affect that war-torn country? The shift in Obama’s approach The trigger for the dramatic shift in American policy was the beheading by ISIS fighters of two American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff. Against this backdrop, widespread criticism regarding Obama’s passive Syria policy had been mounting steadily. Critics took Obama to task for not having intervened in Syria’s civil war earlier, when the emergence of ISIS might have been prevented. Many argued that the negative ramifications of Obama’s passivity went beyond Syria: it emboldened Russia to annex Crimea and destabilize Ukraine, and hardened Iran’s stance in the nuclear talks -- without the fear of major retribution. At the end of the day, what forced Obama’s hand was the combination of this stinging criticism, pressure from sustained lobbying efforts by key US allies, and the significant shift in American public opinion (before the beheadings, 68% of Americans were “for” delaying the use of airpower. -

Reporting ISIS

Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-101, July 2016 The Pen and the Sword: Reporting ISIS By Paul Wood Joan Shorenstein Fellow, Fall 2015 BBC Middle East Correspondent Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. May 2013: The kidnapping started slowly. 1 At first, it did not feel like a kidnapping at all. Daniel Rye delivered himself to the hostage-takers quite willingly. He was 24 years old, a freelance photographer from Denmark, and he had gone to the small town of Azaz in northern Syria. His translator, a local woman, said they should get permission to work. So on the morning of his second day in Azaz, only his second ever in Syria, they went to see one of the town’s rebel groups. He knocked at the metal gate to a compound. It was opened by a boy of 11 or 12 with a Kalashnikov slung over his shoulder. “We’ve come to see the emir,” said his translator, using the word – “prince” – that Islamist groups have for their commanders. The boy nodded at them to wait. Daniel was tall, with crew-cut blonde hair. His translator, a woman in her 20s with a hijab, looked small next to him. The emir came with some of his men. He spoke to Daniel and the translator, watched by the boy with the Kalashnikov. The emir looked through the pictures on Daniel’s camera, squinting. There were images of children playing on the burnt-out carcass of a tank. It was half buried under rubble from a collapsed mosque, huge square blocks of stone like a giant child’s toy. -

Volume X, Issue 1 February 2016 PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 1

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume X, Issue 1 February 2016 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 1 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editor 1 I. Articles Who are the Bangladeshi ‘Islamist Militants’? 2 by Ali Riaz Why is Contemporary Religious Terrorism Predominantly Linked to Islam? Four Possible Psychosocial Factors 19 by Joshua D. Wright How Dangerous Are Domestic Terror Plotters with Foreign Fighter Experience? The Case of Homegrown Jihadis in the US 32 by Christopher J. Wright The Nature of Nigeria’s Boko Haram War, 2010-2015: A Strategic Analysis 41 by James Adewunmi Falode II. Interview In Conversation with Morten Storm: A Double Agent’s Journey into the Global Jihad 53 Interviewed by Stefano Bonino III. Research Note If Publicity is the Oxygen of Terrorism – Why Do Terrorists Kill Journalists? 65 by François Lopez IV. Resources Counting Lives Lost – Monitoring Camera-Recorded Extrajudicial Executions by the “Islamic State” 78 by Judith Tinnes Bibliography: Northern Ireland Conflict (The Troubles) 83 Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes V. Book Reviews Michael Morell. The Great War of our Time. The CIA’s Fight Against Terrorism, from Al Qa’ida to ISIS. New York: Twelve, 2015; 362 pp.; US $ 28.00. ISBN 978-1-4555-8566-3. 111 Reviewed by Brian Glyn Williams ISSN 2334-3745 i February 2016 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 1 Counterterrorism Bookshelf: Twenty New Publications on Israeli & Palestinian Issues 114 Reviewed by Joshua Sinai VI. Notes from the Editor TRI Award for Best PhD Thesis 2015: Deadline of 31 March 2016 for Submissions Approaching 126 About Perspectives on Terrorism 127 ISSN 2334-3745 ii February 2016 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 10, Issue 1 Welcome from the Editor Dear Reader, We are pleased to announce the release of Volume X, Issue 1 (February 2016) of Perspectives on Terrorism at www.terrorismanalysts.com. -

Return to Raqqa

RETURN TO RAQQA 80' - 2020 MEDIAWAN RIGHTS Produced by Minimal Films [email protected] RETURN TO RAQQA 0 2 SYNOPSIS “Return to Raqqa” chronicles what was perhaps the most famous kidnapping event in history , when 19 journalists were taken captive by the Islamic State, as told by one of its protagonists: Spanish reporter Marc Marginedas, who was also the first captive to be released. MARC MARGINEDAS Marc Marginedas is a journalist who was a correspondent for El Periódico de Catalunya for two decades. His activity as a war correspondent led him to cover the civil war in Algeria, the second Chechen war, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the civil war in Syria, among others. On 1 September 2013, Marginedas entered Syria accompanied by a group of opposition figures from the Free Syrian Army. It was his third visit to the country as a correspondent since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011. His main goal during this latest trip was to provide information on the preparations for a possible international military intervention that seemed very close. Three days later, on 4 September 2013, Marginedas was abducted near the city of Hama by ISIS jihadists. His captivity lasted almost six months, during which he shared a cell with some twenty journalists and aid workers from various countries. Two of these were James Foley and Steven Sotloff, colleagues who unfortunately did not share his fate. Marginedas was released in March 2014 and has not returned to Syrian territory since then. But he now feels the need to undertake this physical, cathartic journey to the house near Raqqa where he underwent the harshest experience of his life, an experience that he has practically chosen to forget over the past few years.