Civil War Seminar Professor Warder May 26Th, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 1920

ii^^ir^?!'**i r*sjv^c ^5^! J^^M?^J' 'ir ^M/*^j?r' ?'ij?^'''*vv'' *'"'**'''' '!'<' v!' '*' *w> r ''iw*i'' g;:g5:&s^ ' >i XA. -*" **' r7 i* " ^ , n it A*.., XE ETT XX " " tr ft ff. j 3ty -yj ri; ^JMilMMIIIIilllilllllMliii^llllll'rimECIIIimilffl^ ra THE lot ARC HIT EC FLE is iiiiiBiicraiiiEyiiKii! Vol. XLVII. No. 2 FEBRUARY, 1920 Serial No. 257 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: ]. A. OAKLEY COVER Design for Stained Glass Window FAGS By Burton Keeler ' NOTABLE DECORATIVE SCULPTURES OF NEW YOKK BUILDINGS _/*' 99 .fiy Frank Owen Payne WAK MEMORIALS. Part III. Monumental Memorials . 119 By Charles Over Cornelius SOME PRINCIPLES OF SMALL HOUSE DESIGN. Part IV. Planning (Continued) .... .133 By John Taylor Boyd, Jr. ENGLISH ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION. Part XIII. 155 By Albert E. Bullock PORTFOLIO OF CURRENT ARCHITECTURE . .169 ST. PHILIP'S CHURCH, Brunswick County, N. C. Text and Meas^ ured Drawings . .181 By N. C. Curtis NOTES AND COMMENTS . .188 Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Single copies 35 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD COMPANY 115-119 FOFvIlt I i I IStt I, NEWINCW YORKTUKN WEST FORTIETHM STREET, H v>^ E. S. M tlli . T. MILLER, Pres. W. D. HADSELL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. DODGE. Vice-Pre* ' "ri ti i~f n : ..YY '...:.. ri ..rr.. m. JT i:c..."fl ; TY tn _.puc_. ,;? ,v^ Trrr.^yjL...^ff. S**^ f rf < ; ?SIV5?'Mr ^7"jC^ te :';T:ii!5ft^'^"*TiS t ; J%WlSjl^*o'*<JWii*^'J"-i!*^-^^**-*''*''^^ *,iiMi.^i;*'*iA4> i.*-Mt^*i; \**2*?STO I ASTOR DOORS OF TRINITY CHURCH. -

Appomattox Statue Other Names/Site Number: DHR No

NPS Form 10-900 VLR Listing 03/16/2017 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NRHP Listing 06/12/2017 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Appomattox Statue Other names/site number: DHR No. 100-0284 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Intersection Prince and Washington Streets City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

The Buckeye Bugle

2012 Marshall Hope Award For Most Outstanding Department Newsletter Department of Ohio - Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Volume 12, Issue 1 Summer 2020 THE BUCKEYE BUGLE INSIDE THIS From the Commander’s Tent ISSUE: First and foremost, it is my hope that you and your family are healthy, financially secure, and 2 – History of Gunboat Moses keeping safe. By now I suppose most of us know one or more families that have been impacted by the COVID-19—I hope your family is not among them. Unlike earlier pandemic diseases such as Scarlet 2 – Pvt. Snow Diary Identified Fever, which largely affected children, and Spanish Flu, which was deadly to young adults (especially WWI soldiers), COVID-19 seems to be particularly harmful to people aged 65 and up as well as 2 – Memorial Day Ceremonies individuals with specific health conditions. While I don’t have specific numbers, judging from 3 – Veterans Hall Updates attendance at Departmental and National Encampments that I have participated in, our membership seems to skew towards the higher risk age groups. 3 – Lincoln Statue Delivered So the question seems inevitable: what can we still be doing to support the mission of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War when so many of us are in the high risk category? Let me say this right 3 – Mansfield S.U.V. Badge away: if state, county, or local authorities implement a Corona-virus policy, then Brothers should act in accordance with the policy. Similarly, if an individual’s personal circumstances dictate actions that are 4 – W.R.C. -

The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 40 Number 1 Editorial

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 40 Number 1 Editorial The Artist’s Shadow The Winter Show at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City is always a feast for the eyes. Dazzling works of art, decorative arts, and sculpture appear that we might never see again. During a tour of this pop-up museum in January I paused at the booth of the Alexander Gallery where a painting caught my eye. It was an 1812 portrait of two endearing native-New Yorkers Schuyler Ogden and his sister, the grand-nephew and grand-niece of General Stephen Van Rensselaer. I am always sure that exhibitors at such shows can distinguish the buyers from the voyeurs in a few seconds but that did not prevent the gallery owner from engaging with me in a lively conversation about Fresh Raspberries . It was clear he had considerable affection for the piece. Were I a buyer, I would have very happily bought this little confection then and there. The boy, with his plate of fresh picked berries, reminds me of myself at that very age. These are not something purchased at a market. These are berries he and his sister have freshly picked just as they were when my sisters and I used to bring bowls of raspberries back to our grandmother from her berry patch, which she would then make into jam. I have no doubt Master Ogden and his beribboned sister are on their way to present their harvest to welcoming hands. As I walked away, I turned one last time to bid them adieu and that is when I saw its painter, George Harvey. -

PUCK BUILDING, 295-309 Lafayette Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission April 12, 1983 Designation List 164 LP-1226 PUCK BUILDING, 295-309 Lafayette Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1885-86; addition 1892-93; architect Albert Wagner. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 510, Lot 45. On November 18, 1980, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landuark of the Puck Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.l2). The hearing was continued to Februrary 10, 1981 (Item No.5). Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Five witnesses. spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Puck Building, originally the horne of Puck magazine, is one of the great surviving buildings from New York's old publishing and printing district. The red-brick round-arched structure occupies the entire block bounded by East Houston, Lafayette, Mulberry and Jersey Streets, and has been one of the most prominent architectural presences in the area since its construction one hundred years ago. The building is further distinguished by the large statue of Puck at the building's East Houston and Mulberry Street corner; this is among the city's most conspicuous pieces of architectural sculpture. Puck was, from its founding in 1876 until its demise in 1918, the city's and one of the country's best-kno;vn humor magazines. Published in both English and German-language editions, Puck satirized most of the public events of the day. The magazine featured color lithographic cartoons produced by the J. -

Year 4 - Course Book History

history year 4 - course book History ONLY Year 4 Course BookUSE FOR SAMPLE This book has been compiled and written by Jenny Phillips, NOTMaggie Felsch, Megan Bolich, and Chris Jones. ©2019 Jenny Phillips | www.GoodandBeautiful.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be copied or reproduced in any way without written permission from the publisher. Table of Contents About this Course .................................................................................................iv Read-Aloud Suggestions .......................................................................................vii Unit 1: Ancient Rome Lesson 1: An Introduction to Ancient Rome ..........................................................3 Lesson 2: The Founding of Rome ..........................................................................5 Lesson 3: The Expansion of Rome .........................................................................6 Lesson 4: From Republic to Empire .......................................................................7 Lesson 5: Daily Life in Rome .................................................................................15 Lesson 6: The Spread of Christianity .....................................................................ONLY16 Lesson 7: Constantine the Great ...........................................................................17 Lesson 8: Theodosius I to the Fall of Rome ...........................................................USE18 Lesson 9: The Byzantine Empire............................................................................20 -

Remembering the Veteran Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915

REMEMBERING THE VETERAN DISABILITY, TRAUMA, AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1915 Erin R. Corrales-Diaz A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Ross Barrett Bernard L. Herman John P. Bowles John Kasson Eleanor Jones Harvey © 2016 Erin R. Corrales-Diaz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erin R. Corrales-Diaz: Remembering the Veteran: Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915 (Under the direction of Ross Barrett) My dissertation, “Remembering the Veteran: Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915,” explores the complex ways that American artists interpreted war-induced disability after the Civil War. Examining pictorial representations of disabled veterans by George Inness, Thomas Nast, William Bell, and other artists, I argue that the veteran’s broken body became a vehicle for exploring the overwhelming sense of loss that Northerners and Southerners experienced in the war's aftermath. Oscillating between aestheticized ideals and the reality of affliction, visual representations of disabled veterans uncover postwar Americans’ deep and otherwise unspoken anxieties about masculinity, identity, and nationhood. This project represents the first major effort to historicize the visual culture of war-related disability and presents a significant deviation from previous Civil War scholarship and its focus on death. In examining these understudied representations of disability and tracing out the ways that they rework and reinforce nineteenth-century constructions of the body, this project models an approach to the analysis of period imaginings of corporeal difference that might in turn shed new light on contemporary artistic responses to physical and psychological injuries resulting from warfare. -

Ancient & Historic

Ancient & Historic METALS CONSERVATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Ancient & Historic METALS CONSERVATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Proceedings of a Symposium Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Conservation Institute November 1991 Edited by DAVID A. SCOTT, JERRY PODANY, BRIAN B. CONSIDINE THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Symposium editors: David A. Scott, the Getty Conservation Institute; Jerry Podany and Brian B. Considine, the-J. Paul Getty Museum Publications coordination: Irina Averkieff, Dinah Berland Editing: Dinah Berland Art director: Jacki Gallagher Design: Hespenheide Design, Marilyn Babcock / Julian Hills Design Cover design: Marilyn Babcock / Julian Hills Design Production coordination: Anita Keys © 1994 The J. Paul Getty Trust © 2007 Electronic Edition, The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in Singapore Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient & historic metals : conservation and scientific research : proceedings of a symposium organized by the J.-Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Conservation Institute, November 1991 / David A. Scott, Jerry Podany, Brian B. Considine, editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-231-6 (pbk.) 1. Art metal-work—Conservation and restoration—Congresses. I. Scott, David A. II. Podany, Jerry. III. Considine, Brian B. IV. J. Paul Getty Museum. V. Getty Conservation Institute. VI. Title: Ancient and historic metals. NK6404.5.A53 1995 730’.028—dc20 92-28095 CIP Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the photographs and illustrations in this book to obtain permission to publish. Any omissions will be corrected in future editions if the publisher is contacted in writing. Cover photograph: Bronze sheathing tacks from the HMS Sirius. -

The Conservation of American War Memorials Made of Zinc

THE CONSERVATION OF AMERICAN WAR MEMORIALS MADE OF ZINC CAROL A. GRISSOM AND RONALD S. HARVEY ABSTRACT-Affordable war memorials featuring Deuxiemement il y a les pretendues statues en bronze soldiers made of zinc were purchased by small blanc, towns qui sont elles aussi coulees piece par piece dans throughout the United States following the des Civilmoules en sable, mais sont assemblies de fagon War, and the practice continued to a lesser discrete extent en utilisant du zinc liquide sur le verso des after the Spanish-American and First World joints. Wars. Ces statues sont ensuite soumises au jet de Such memorials can be generally divided into sable three pour leur donner l'aspect de la pierre et erigees groups defined by fabrication techniques: (1) soit imita- sur des piedestaux de magonnerie, soit sur des tion bronze statues sand-cast in pieces, assembled bases faites by de plusieurs couches de bronze blanc, ce soldering, painted with "bronze" paint, and placedqui cree on dans certains cas d'6normes monuments masonry pedestals or cast-iron fountains; (2) entierementso-called faits de zinc. Troisiemement il y a les white-bronze statues assembled using molten statues zinc tocomposees de feuilles de zinc estamp6es, qui back unobtrusively located joins between sand-cast ont ete soudees ou rivetees ensemble sur des arma- pieces, sandblasted to appear stonelike, and displayedtures en metal et finalement peintes. Les dommages on masonry pedestals or multilayered white-bronze les plus frequents sur ces statues en zinc sont causes bases that in some cases created enormous monu- par la rupture du metal de fonte qui est relativement ments made entirely of zinc; and (3) statues stamped cassant. -

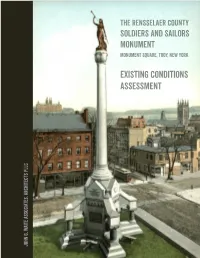

Existing Conditions Assessment

THE RENSSELAER COUNTY SOLDIERS AND SAILORS MONUMENT Monument Square, Troy, New York Existing Conditions Assessment Rensselaer County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Existing Conditions Assessment - 1 John G. Waite Associates, Architects PLLC Architects Associates, John G. Waite The Rensselaer County SOLDIERS AND SAILORS MONUMENT MONUMENT SQUARE, TROY, NEW YORK Existing Conditions Assessment May 2017 John G. Waite Associates, Architects PLLC 384 Broadway, Albany NY 12207 64 Fulton Street, Suite 402, New York, NY 10038 CITY OF TROY Laura Welles JOHN G. WAITE ASSOCIATES, ARCHITECTS PLLC 384 Broadway, Albany, New York 12207 64 Fulton Street, Suite 402, New York, New York 10038 John G. Waite, FAIA William Brandow Chelle Jenkins CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................6 EXISTING CONDITIONS ..................................................................................................................... 8 RECOMMENDATIONS WITH BUDGET COSTS ..................................................................................12 PHOTOGRAPHS ................................................................................................................................14 APPENDICES Appendix A: Report from The Monumental News Appendix B: Excerpt from Troy’s One Hundred Years 1789-1889 Appendix C: Rensselaer County Soldiers and Sailors Monument Association Records INTRODUCTION Troy’s Monument Square is a triangle of land in the heart of the city’s -

The Image Business: Shop and Cigar Store Figures in America

The Image uring the height of their popularity, carved wooden figures advertising a wide variety of goods and services were a common sight on the Dstreets of urban and small-town America. Tens of thousands of shop figures were carved in the United States and Canada in the eighteenth and nine- teenth centuries. Images of Native Americans were by far the most popular, but any character that caught the public's imagination—especially after about 1860—could and would be skillfully personified, from the more traditional Turks and Scotsmen to up-to-date baseball players and fashionable ladies. The carvers themselves coined the phrase "the image business" to characterize the wide range of figures that they were called upon to create.' Whether rendered in detailed real- ism or a more stylized and individualized fashion, shop figures represent one of the largest and most expressive of all American sculptural traditions. As reflec- tions of their era, they also speak volumes about several important aspects of American social history, including racial and gender stereotyping, the emergence of a national popular culture, and the birth of modern commercial advertising. 54 WINTER 1996/97 FOLK ART INDIAN PRINCESS WITH CROSSED LEGS Incised "S.A. Robb, Carver, 114 Centre St." on base New York City 1888-1903 Polychromed wood 7r high Collection of Allan and Penny Katz Business Shop and Cigar Store Figures in America By Ralph Sessions FATHER TIME Shop figures were so much a tures made during this time were cre- Artist unknown part of the American scene that no one ated by shipcarvers trained in tradi- Mohawk Valley, New York c. -

National Register of Historic Places City, Town 1100 L Street, N.W., Washington State D.C

NPS Form 10-900 NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION OMB NO. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register off Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Pension Building andorcommon Same; also National Building Museum 2. Location street & number 4th, 5th, F § G Streets, N.W. (north side, Judiciary Sq^^_ not for publication city, town Washington __ vicinity of state D.C. code 08 county District of Columbia code 001 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district x public x occupied agriculture x museum x building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress x educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted x government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner off Property name General Services Administration street & number 18th and F Street, N.W. city, town Washington_______________ vicinity of_____________state D.C. 5. Location off Legal Description________ courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Recorder of Deeds street & number 6th and D Streets, N.W. city, town________Washington, D.C._________________________state________________ 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ title_ J^a^ional Register of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? x yes --.no date_February 2Q_, 1969 federa[ _ state ___ county _ local depository for survey records National Register of Historic Places city, town 1100 L Street, N.W., Washington state D.C. 7.