Double Jeopardy and Summary Contempt Prosecutions David S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Terminology

Legal Terminology A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A ABATES – CAUSE: Used in Criminal Division cases when the defendant has died, so the “cause” (the case) “abates” (is terminated). ACQUITTED: Defendant is found not guilty ADJUDICATION HEARING: In child abuse and neglect proceedings, the trial stage at which the court hears the state’s allegations and evidence and decides whether the state has the right to intervene on behalf of the child. In a juvenile delinquency case, a hearing in which the court hears evidence of the charges and makes a finding of whether the charges are true or not true. ADMINISTRATOR: Person appointed to oversee the handling of an estate when there is no will. ADMONISHED: A reprimand or cautionary statement addressed to an attorney or party in the case by a judge. AFFIANT: One who makes an affidavit. AFFIDAVIT: A written statement made under oath. AGE OF MAJORITY: The age when a person acquires all the rights and responsibilities of being an adult. In most states, the age is 18. ALIAS: Issued after the first instrument has not been effective or resulted in action. ALIAS SUMMONS: A second summons issued after the original summons has failed for some reason. ALIMONY: Also called maintenance or spousal support. In a divorce or separation, the money paid by one spouse to the other in order to fulfill the financial obligation that comes with marriage. ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION: Methods for resolving problems without going to court. -

The History of the Contempt Power

Washington University Law Review Volume 1961 Issue 1 January 1961 The History of the Contempt Power Ronald Goldfarb New York University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Recommended Citation Ronald Goldfarb, The History of the Contempt Power, 1961 WASH. U. L. Q. 1 (1961). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1961/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY LAW QUARTERLY Volume 1961 February, 1961 Number 1 THE HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPT POWER* Ronald Goldfarbi" INTRODUCTION Contempt can be generally defined as an act of disobedience or dis- respect toward a judicial or legislative body, or interference with its orderly process, for which a summary punishment is usually exacted. In a grander view, it is a power assumed by governmental bodies to coerce cooperation, and punish criticism or interference, even of a causally indirect nature. In legal literature, it has been categorized, subclassified, and scholastically dignified by division into varying shades--each covering some particular aspect of the general power, respectively governed by a particular procedure. So, the texts separate retributive or criminal coritempts from merely coercive or civil con- tempts--those directly offensive from those only constructively con- temptuous-those affecting the judiciary and others the legislature. The implementation of this power has taken place predominantly in England and America, and has recently been accelerated into a con- tinuingly greater role in the United States. -

CH 12 Contempt of Court

CONTEMPT OF COURT .............................................................................. 1 §12-1 General Rules .............................................................................................. 1 §12-2 Direct Contempt and Indirect Contempt ............................................. 4 §12-3 Conduct of Counsel and Pro Se Litigant .............................................. 9 §12-4 Violating Court Orders ........................................................................... 14 §12-5 Other Conduct .......................................................................................... 17 §12-6 Sentencing ................................................................................................. 19 i CONTEMPT OF COURT §12-1 General Rules United States Supreme Court Codispoti v. Pennsylvania, 418 U.S. 506, 94 S.Ct. 2687, 41 L.Ed.2d 912 (1974) An alleged contemnor may be summarily tried for acts of contempt that occur during a trial, and may receive a sentence of no more than six months. In addition, the judge may summarily convict and punish for separate contemptuous acts that occur during trial even though the aggregate punishment exceeds six months. However, when a judge postpones until after trial contempt proceedings for various acts of contempt committed during trial, the contemnor is entitled to a jury trial if the aggregate sentence is more than six months, even though each individual act of contempt is punished by a term of less than six months. Gelbard v. U.S., 408 U.S. 41, 92 S.Ct. 2357, 33 L.Ed.2d 179 (1972) In defense to a contempt charge brought on the basis of a grand jury witness's refusal to obey government orders to testify before the grand jury, witness may invoke federal statute barring use of intercepted wire communications as evidence. Groppe v. Leslie, 404 U.S. 496, 92 S.Ct. 582, 30 L.Ed.2d 632 (1972) Due process was violated where, without notice or opportunity to be heard, state legislature passed resolution citing person for contempt that occurred two days earlier. -

Criminal Contempt of Court Procedure: a Protection to the Rights of the Individual

VOL . XXX MARCH 1951 NO . 3 Criminal Contempt of Court Procedure: A Protection to the Rights of the Individual J. C. MCRUERt Toronto What I have to say may be prefaced by two quotations, the first from Chambers Encyclopaedia : There is probably no country in which Courts of Law are not furnished with the means of vindicating their authority and preserving their dignity by calling in the aid of the Executive in certain circumstances without the formalities usually attending a trial and sentence. Of .this the simplest instance is where the Judge orders the officers to enforce silence or to clear the court. and the second from Bacon's Abridgment: Every court of -record, as incident to it, may enjoin the people to keep silence, under a pain, and impose reasonable fines, not only *on such as shall be convicted before them of any crime on a formal prosecution, but also on all such as shall be guilty of any contempt in the face of the court, as by giving opprobrious language to the judge, or obstinately refusing to do their duty as officers of the Court and may immediately order them into custody.' . To. these I add two other quotations: A Court of Justice without power to vindicate its own dignity, to enforce obedience to its mandates, to protect its officers, or to shield those who are * Based on an address delivered to the Lawyers Club, Toronto, on January 24th, 1952 . t The Hon . J. C. McRuer, Chief. Justice, High Court of Justice, Ontario . ' (7th ed.) Vol . 2, p. -

The Constitution and Contempt of Court

Michigan Law Review Volume 61 Issue 2 1962 The Constitution and Contempt of Court Ronald Goldfarb Member of the California and New York Bars Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, First Amendment Commons, Fourth Amendment Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Ronald Goldfarb, The Constitution and Contempt of Court, 61 MICH. L. REV. 283 (1962). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol61/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTEMPT OF COURT* Ronald Goldfarbt l. INTRODUCTION HE contempt power of American courts is as old as our judi T ciary itself and, while derived from historical common-law practices, is peculiar both to and within American law. It is pecu liar to American law in that other legal systems (not based on the English) have no such power of the nature or proportions of ours.1 It is peculiar within our system in that no other of our legal powers is comparable to contempt in pervasiveness or indefiniteness. Nor does any analogy come to mind of a legal power with the inherent constitutional anomalies characteristic of contempt. -

Omissions and Criminal Liability

OMISSIONS AND CRIMINAL LIABILITY J. PAUL McCUTCHEON INTRODUCTION The question of liability for omissions raises issues of profound significance for the criminal law. While discussion thereof might be predominently theoretical - in practice prosecutors are likely to encounter few omissions cases - it is nevertheless impOltant as it embraces consideration of the proper scope of the criminal law, its function in the prevention of harm and the en couragement of socially beneficial conduct and the practical effectiveness and limits of the criminal sanction. Although it has not been seriously considered by Irish courts the issue has attracted the attention of courts and jurists in other jurisdictions. I The Anglo-American tradition is one ofreluctance to penalise omissions; to draw on the time honoured example no offence is committed by the able-bodied adult who watches an infant drown in a shallow pool. That gruesome hypothetical is happily improbable, but the general proposition is substantiated by the much-cited decision in People v. BeardsleyZ where it was held that the accused was not criminally answerable for the death from drug use of his 'weekend mistress' in circumstances where he failed to take the necessary, and not unduly onerous, steps to save her life. Likewise, the law does not impose a general duty to rescue those who are in peril nor is there a duty to warn a person of impending danger.3 A passive bystander or witness is not answerable for his failure to act, even where the harm caused is the result of criminal conduct.4 This general reluctance is evident in the manner in which criminal offences are defined. -

Criminal and Civil Contempt: Some Sense of a Hodgepodge

St. John's Law Review Volume 72 Number 2 Volume 72, Spring 1998, Number 2 Article 3 Criminal and Civil Contempt: Some Sense of a Hodgepodge Lawrence N. Gray Esq. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CONTEMPT: SOME SENSE OF A HODGEPODGE LAWRENCE N. GRAY, ESQ.' INTRODUCTION In one way or another, the law of contempt permeates all law because force-not morality-is the ultimate sanction. Those who will not obey, or disrupt, are to be coerced and pun- ished in the name of the law. In law school, contempt is a word used frequently but seldom defined beyond a few maxims, such as something about the key to one's own jail cell. After law school, contempt becomes a word secretly feared by those who threaten it-probably as much as those who are threatened with it. Contempt should be a required course in law school or at least 90% of any course in professional responsibility. From a personal perspective as one who has read and studied contempt for close to thirty years, the latest erroneously- reasoned decision holds no awe because there is always an in- ventory of other erroneous decisions available to neutralize its pontifications about something being "well settled"-leaving the comparatively precious few classics, which have been soundly reasoned and correctly decided, free to fix the right. -

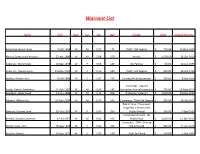

Warrant List

Warrant List Name DOB Race Sex Hgt Wgt Charge Bond Date of Warrant Ackerman, Bruce Leslie 7-Oct-1968 W M 5 07 175 Theft - 5th Degree $ 274.44 20-Nov-2001 Alvarez Gomez,Jose Antonio 27-Apr-1980 W M 5 08 150 Assault $ 1,500.00 16-Oct-2019 Anderson, Mary Helen 19-Dec-1978 W F 5 09 180 No Parking $ 50.00 22-Jun-1999 Anderson, Tammy Lynn 29-May-1967 W F 5 10 180 Theft - 5th Degree $ 500.00 24-Oct-1996 Apolito, Amber Lynn 26-Jul-1990 W F 5 07 155 Driving While Suspended $ 350.00 9-Sep-2020 Contempt - Expired Austin, Derrick Lawrence 11-Apr-1987 W M 5 09 145 Insurance; Annual Inspection $ 750.00 23-May-2014 Baardson, Jacob David 13-Jun-1989 W M 5 11 260 Probation Violation $ 2,000.00 20-Nov-2020 Baldwin, William Earl 21-Nov-1970 W M 5 09 165 Contempt - Theft 5th Degree $ 350.00 26-Oct-2015 Public Intox / Possession Drug Para / Harassment Barbosa, Cortney Leah 29-Oct-1991 W F 5 09 250 Public Official $ 350.00 9-Sep-2020 Contempt of Court - (2) Bendlin, Donald Lawrence 17-Jul-1967 W M 6 01 150 Public Intox $ 1,000.00 11-Dec-2019 Contempt - OWI / Driving Benton, Sara Lynn 28-Aug-1978 W F 5 09 205 While Barred $ 500.00 21-Jan-2016 Bentten, Dawn L 24-Sep-1972 W F 5 03 140 Theft by Check $ 350.00 7-Feb-2003 Bittner, Dennis Carroll 20-Jul-1956 W M 6 00 210 Theft - 5th Degree $ 200.00 9-Oct-1995 Driving Under Influence - Bramley, Dustin W 21-Jul-1980 W M 6 01 220 Drugs $ 2,500.00 13-Oct-2015 Contempt - Lavicous Acts Branning, William David 30-Dec-1974 W M 5 06 175 with Child $ 375.00 19-Aug-2010 Brennan, Kevin Lee 14-May-1967 W M 5 10 175 Contempt - -

Permitting Private Initiation of Criminal Contempt Proceedings

NOTES PERMITTING PRIVATE INITIATION OF CRIMINAL CONTEMPT PROCEEDINGS In some states, those who violate court orders can be punished by privately initiated proceedings for criminal contempt.1 Other jurisdic- tions forbid such an arrangement.2 The Supreme Court has instructed the federal courts to appoint only “disinterested” private prosecutors when exercising their inherent authority to punish contempt.3 Of course, the question of who can bring a criminal contempt proceeding affects a wide range of interests — a range just as broad as that pro- tected by court orders in the first place. Any victor in a civil lawsuit may someday undertake a contempt proceeding to preserve that victo- ry: so with the multinational corporation seeking to protect its patents, so with the parent attempting to enforce her custody arrangement. The doctrine of contempt assumes that civil proceedings will be suffi- cient to enforce a court order; criminal contempt is distinguished from its civil counterpart in that it punishes noncompliance rather than merely encouraging compliance. In practice, however, civil contempt can adequately discourage only ongoing violations of a court order. To jail a contemnor for what he did last Tuesday, criminal contempt is re- quired.4 And so it matters a great deal whether the beneficiary of a civil protective order can initiate criminal contempt proceedings, or whether she is limited to civil contempt: episodes of physical abuse are always in the past when the court learns of them. Last year, the Supreme Court discussed the question of who could initiate proceedings for criminal contempt, but ultimately dismissed the case on which that discussion had been based. -

Child Support Bench Book: Indirect Civil Contempt for Failure to Pay Child Support TABLE of CONTENTS

Child Support Bench Book: Indirect Civil Contempt for Failure to Pay Child Support TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 A. Legal Authority................................................................................................................... 1 II. Overview of Contempt Action .................................................................................................. 2 A. Prima Facie Case & Burden of Proof................................................................................. 2 B. Purpose................................................................................................................................ 2 C. Sentencing ........................................................................................................................... 3 D. Court Liaison Program........................................................................................................ 3 E. Is Contempt a Good Remedy?............................................................................................. 3 III. Screening Process .................................................................................................................... 4 A. Review and Research.......................................................................................................... 4 B. Assessing Case against Obligor ......................................................................................... -

Supreme Court of the United States Petition for Writ of Certiorari

18--7897 TN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STAIET FILED ' LARAEL OWENS., Larael K Owens 07 MARIA ZUCKER, MICHEL P MCDANIEL, POLK COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, MARK MCMANN, TAMESHA SADDLERS. RESPONDENT(S) Case No. 18-12480 Case No. 8:18-cv-00552-JSM-JSS THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Larael K Owens 2 Summer lake way Savannah GA 31407 (229)854-4989 RECE11VED 2019 I OFFICE OF THE CLERK I FLSUPREME COURT, U.sJ Z-L QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1.Does a State Judges have authority to preside over a case when He/She has a conflicts of interest Does absolute immunity apply when ajudge has acted criminally under color of law and without jurisdiction, as well as actions taken in an administrative capacity to influence cases? 2.Does Eleventh Amendment immunity apply when officers of the court have violated 31 U.S. Code § 3729 and the state has refused to provide any type of declaratory relief? 3.Does Title IV-D, Section 458 of the Social Security Act violate the United States Constitution due to the incentives it creates for the court to willfully violate civil rights of parties in child custody and support cases? 4.Has the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit erred in basing its decision on the rulings of a Federal judge who has clearly and willfully violated 28 U.S. Code § 455. .Can a state force a bill of attainder on a natural person in force you into slavery 6.Can a judge have Immunity for their non judicial activities who knowingly violate civil rights 2. -

State V. Banks

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** STATE OF CONNECTICUT v. DUANE BANKS (AC 17786) Schaller, Hennessy and Mihalakos, Js. Argued January 27Ðofficially released August 1, 2000 Counsel Harry Weller, senior assistant state's attorney, with whom, on the brief, were James E. Thomas, state's attorney, Warren Maxwell, senior assistant state's attor- ney, and Edward Narus, assistant state's attorney, for the appellant (state).