Prevention of Alcohol- Related Hiv Risk Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wine Bar Volunteers

Wine Bar Volunteers One hour before performance Hang coat and place personal belongings in Purple Room. Purses may be stored in box office if volunteer is not comfortable leaving in Purple Room. Get name tag in Box Office and sign in. Immediately plug in coffee maker (takes about 10 minutes to warm up); green light must appear before you make coffee. Set out wine/beer displays, signage, coffee tray, tea basket, napkins, glasses and tip jars. Start tip jars with $1 from cash box. See diagram/photo of Wine Bar set up. Get Wine Bar cash bag from House Manager. Bag should contain $200 for the register, and keys for the Wine Bar cabinets, wine refrigerator and beer cooler. Make coffee starting with hot water (for cocoa and tea), non-caffeinated coffee and then caffeinated coffee. Set 8 cups next to each coffee/water pot; this will help you know when to brew new pot, as each pot holds 8 cups. See separate coffee making instructions for more detail, if needed. 45 minutes before start of show Be familiar with wines and beers for sale (see cheat sheet), and prices of all beverages. Assist guests with purchases. Let them know that they may take drinks into theater (but no glass containers, see below). Pour wine and beer into plastic glass. The exception is Surly beer; you may serve in can with top popped. Ask for proper ID (anyone who looks under 35) and ticket proof for alcohol sales; anyone purchasing alcohol must be attending the performance. Use tally sheet to record all CASH sales of coffee, tea, hot chocolate or water (anything other than alcohol) by placing a ‘hash mark’ under the title of item sold. -

Japan Wine Report 2012 Wine Annual Japan

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 2/21/2013 GAIN Report Number: JA3501 Japan Wine Annual Japan Wine Report 2012 Approved By: Steve Shnitzler, Director Prepared By: Sumio Thomas Aoki, Senior Marketing Specialist Kate Aoki, Intern Steven Ossorio, Intern Report Highlights: In 2012, the United States held a 7.7% value share of Japan's $1,037 million imported bottled wine market. This was an increase from the 7.5% share in 2011. Market share of bottles priced ¥500 JPY ($6.33) or under and ¥1000 – 1500 JPY ($12.66 – 18.99 USD) continue to increase. Bulk wine imports continue to grow as domestic Japanese wine companies bottle their own wine. Executive Summary: Executive Summary Distribution of Japanese bottled wine is approximately 900 thousand hectoliters. This plus 1.81 million hectoliters of imported bottled wines totaled 2.71 million hectoliters of wine distributed in Japan. The Japanese wine market continues to be very competitive. Although 50 countries supply wine to Japan, ten countries account for approximately 96% of the imported volume. On-premise consumption continues to increase as the Japanese economy improves and wine becomes more generally affordable. Upscale Japanese izakaya restaurants are performing quite well, and standing wine bars are becoming more popular, particularly among middle-aged and older men. Off-premise o Off-premise consumption has increased as well. Supermarkets are carrying more inexpensive (under ¥1000 JPY or $12.66) wines, and premium wines are increasingly being consumed from online sources. -

Bar Selections OPTION #1 HOSTED BAR PACKAGE

The Lynnwood Foundation, a nonprofit, maintains and preserves The Duke Mansion, and created and operates The Lee Institute. 400 Hermitage Road, Charlotte, NC 28207 Tel: 704.714.4400 Fax 704.714.4435 [email protected] www.dukemansion.org Bar Selections OPTION #1 HOSTED BAR PACKAGE Premium Bar Package OPTION #2 $22 per person for the first hour HOSTED BAR BY CONSUMPTION $12 per person for each additional hour Premium Liquor, Imported and Domestic Beer, Drink consumption is tallied by the bartender for the duration of House Wine and Champagne, the evening and the host is charged accordingly at the end of Sodas and Mineral Water the event. Standard Bar Package $20 per person for the first hour $10 per person for each additional hour Standard Liquor, Imported and Domestic Beer, OPTION #3 House Wine and Champagne, CASH BAR Sodas and Mineral Water Your guests are charged for each drink as it is ordered. Beer and Wine Bar Ask your Catering Manager for the Cash Bar Price List. $16 per person for the first hour Cash Bar option does require a minimum of $150.00 in bar sales. $8 per person for each additional hour Imported and Domestic Beer, House Wine and Champagne, Sodas and Mineral Water SPECIALTY BARS AVAILABLE Package bars include unlimited consumption Wine service with dinner is included if your package bar is open during dinner. BARTENDER FEE HOSTED BAR CONSUMPTION PRICES COCKTAIL SERVICE North Carolina law requires bartenders for all bar set ups. Wine Charged per Bottle See Wine List For groups of 12 people of less, you may arrange for cocktail service, A $75.00 bartender fee is added Domestic Beer $6 per bottle instead of having a full bar set up per bar for the first Imported Beer $7 per bottle at your event. -

Upscale Wine Bar / Gaming Establishment

Upscale Wine Bar / Gaming Establishment Location: Coming Soon p. 630-605-4060 [email protected] [Web address] Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 3 Highlights Objectives Mission Statement Keys to Success II. Description of Business......................................................................................... 5 Products and Services Service Locations Interior Hours of Operation Suppliers III. Business Structure ................................................................................................. 8 Company Ownership/Legal Entity Management Employees Financial Management IV. Marketing ............................................................................................................. 13 Market Analysis Market Segmentation Competition Pricing V. Appendix ............................................................................................................... 18 Start-Up Expenses/Capital Funding Sought Cash Flow/Income Projection Sales Forecast Break-Even Analysis Miscellaneous Documents THIS DOCUMENT IS THE EXCLUSIVE PROPERTY OF Matt Juntunen and Donald Thatcher and the entities they create to implement this plan (Owners). All information, data and drawings, in any form, embodied in this presentation or its companion documents, or in accompanying verbal presentations, is strictly confidential and is supplied to recipient solely on the understanding that recipient will hold it confidentially, and not -

Click Here to View Complete Wedding Brochure

RENDITIONS A service charge of 22%, as well as appropriate taxes, will be applied to all food and beverage purchases. Renditions is the perfect choice for your wedding ceremony and reception. We have seating for up to 175 guests with a large dance floor and a separate room for cocktails. Both rooms overlook the golf course with an outside patio available for your guest’s enjoyment. The photo opportunities are too numerous to name and riding on the golf cart is always loads of fun. Not to mention our award-winning chef who has been with us for over 8 years and a staff who will attend to you and your guests all day long. The ballroom is very versatile, you can make the décor your own and your favorite colors will always “pop” right into place. You will have exclusive use of Renditions Ballroom Including Tables, Chairs, China, Flatware and Glassware, Large Dance Floor, Get Ready Room, Linens, Food and Beverage, Complimentary Cake Cutting, Professional Wait Staff, Food Tasting for 2, Complimentary Parking, Ceremony on the Green for Half Hour, One Hour Cocktail Reception, Three Hour Reception. When you host your reception at Renditions you will receive 20% off your rehearsal dinner and/or wedding shower. A service charge of 22%, as well as appropriate taxes, will be applied to all food and beverage purchases. Room Rental 2021 Friday & Sunday - Ceremony 100 | Lounge &| Ballroom 500 Saturday – Ceremony 200 | Lounge &Ballroom 800 *2022 Friday & Sunday - Ceremony 200 | Lounge &| Ballroom 600 Saturday – Ceremony 300 | Lounge &Ballroom 900 *please -

Cibo Wine Bar in Coral Gables Set to Open October 26 - Miami Restaurants and Dining - Short Order 11-09-23 11:29 AM

Cibo Wine Bar in Coral Gables Set to Open October 26 - Miami Restaurants and Dining - Short Order 11-09-23 11:29 AM Browse Voice Nation Most Popular | Most Recent Sign up Log in Blogs Search Miami New Times Food News Chef Interviews South Beach Wine & Rumor Mill TOP Pumpkin Haven is Kitchen LeeFood... Schrager Did Chef Mike Shortage to Ruin Heaven to Chef Talks Food Sabin Leave blog Halloween Todd Erickson Trucks and Prime One Antonio Twelve? STORIES By Anais Alexandre By Lesley Elliott By Lee Klein Banderas By Riki Altman Restaurant Opening Cibo Wine Bar in Coral Gables Set to Open Most Popular Stories October 26 Viewed Commented Recent By Mandy Baca Tue., Sep. 20 2011 at 9:00 AM Resorts World Miami Includes Plans For Over 50 Categories: Restaurant Opening Restaurants Share Like 1 0 0 tweet 0 digg Derek Tresize, Vegan Bodybuilder: Meat Grows StumbleUpon Muscles and Cancer Have you walked by the old Sports Exchange location lately? If you frequent Tarpon Bend Obama Beer? The President's White House Honey Ale Raw Bar & Grill (or David's Bridal), you might Vegan Bodybuilder Danny David Sprouts Muscles have already noticed the movement next door. Naturally, Part 1 To be located at 45 Miracle Mile, Cibo Wine Bar Top Five New Restaurants: Beyond Best of Miami is tentatively set to open soon -- October 26 to be exact. More Most Popular... The rustic Italian wine bar by Liberty Entertainment Group out of Toronto goes by the following motto: "Prepare for an Old World revolution." Are you ready, Coral Gables? The entertainment group is also responsible for the Liberty Caffe located inside the Coral Gables Country Club, offering casual fare for country-club-goers. -

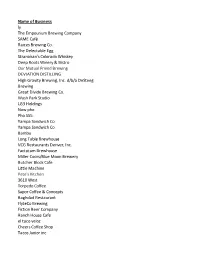

TEP Approved List.Xlsx

Name of Business ly The Empourium Brewing Company SAME Café Raices Brewing Co. The Delectable Egg Stranahan's Colorado Whiskey Deep Roots Winery & Bistro Our Mutual Friend Brewing DEVIATION DISTILLING High Gravity Brewing, Inc. d/b/a DeSteeg Brewing Great Divide Brewing Co. Wash Park Studio LG3 Holdings Now pho Pho 555 Yampa Sandwich Co Yampa Sandwich Co Bambu Long Table Brewhouse VCG Restaurants Denver, Inc. Factotum Brewhouse Miller Coors/Blue Moon Brewery Butcher Block Cafe Little Machine Pete's Kitchen 3610 West Torpedo Coffee Sapor Coffee & Concepts Baghdad Restaurant FlyteCo Brewing Fiction Beer Company Ranch House Cafe el taco veloz Cheers Coffee Shop Tacos Junior inc Machete The Pioneer The Way Back The Preservery RiNo Barbecue, LLC/Smok Governess, LLC Born Hotel & Citizen Rail Zocalito Latin Bistro Beast + Bottle Restaurant The District Dive Inn Bierstadt Lagerhaus Tivoli Brewing Company Taphouse The Lobby Berkeley Inn Federal Bar & Grill Valentinos Restaurant, LLC dba Zane's Italian Bistro Hudson Hill ANNIE'S CAFE Blue Bonnet Restaurant Corp Ristorante Piatti Candlelight Tavern South Broadway Country Club Ambli Gourmet Maria Empanada The Walnut Room Esters The Crow Bar Lucile's Stoic & Genuine Cana Wine Bar The Irish Snug The Goods Mile High Station Mezcal Goosetown Tavern LITTLE INDIA CUISINE 100% De Agave Mexican Grill and Cantina Swanky's Denver Deep Dish Bad Daddy's Burger Bar Cucina Colore Field House Rioja Bistro Vendome Just Be Kitchen LLC Highland Tap & Burger Hop Alley The Hound Sports Pub + Burger Trade Tavern Jack -

Functions and Events at BFPL Bfplperth.Com TIME WELL SPENT 1 Welcome to Brookfield Place

i Functions and Events at BFPL BFPLPerth.com TIME WELL SPENT 1 Welcome to Brookfield Place PERTH’S GO-TO FASHION, DINING AND EVENT DESTINATION IN THE HEART OF THE CBD. Welcome to Brookfield Place, Perth’s Adjacent to the Perth Convention All venues employ professional and go-to destination for dining and and Exhibition Centre, Elizabeth skilled function staff who work events in busy St Georges Terrace Quay, and just a short walk from with you to identify your individual at the heart of the CBD. Combining RAC Arena, Brookfield Place is needs, ensuring a premium, hassle- world-class architecture with conveniently located to deliver all free, and memorable experience for outstanding amenities, you’ll never your function and event needs, all guests. be in want of choice or style for your catering for all varieties of guests. next event, big or small. Brookfield Place’s lively mix of bars Access to and from the precinct is and restaurants include Arlo by Our venues are keenly sought-after made easy with the Elizabeth Quay Mo, Bar Lafayette, Basilica, Bob’s destinations for the surrounding train and bus station on Mounts Bar, Bobèche, Grill’d, Print Hall, The corporate market, providing a Bay Road, and taxi and Uber pick Apple Daily Bar & Eating House, The diverse choice of dining, function up points on St Georges Terrace. Heritage Wine Bar and W Churchill. and event experiences for special occasions and celebrations. 2 Contents Bar Lafayette ................................................................................................. 03 -

Clowns Wine Bar & Jesters Nightclub

FREEHOLD GUIDE PRICE - £1,000,000 LEASEHOLD GUIDE PRICE - PREMIUM £75,000 CLOWNS WINE BAR & JESTERS NIGHTCLUB 112-118 Bevois Valley Road, Southampton, Hampshire, SO14 0JZ Key Highlights • Substantial mid- terrace plot • Well-known business in established • Within catchment of Central Business leisure location District and University circuit • 9,396 square feet (872.87 square metres) • Substantial ground floor and basement • Redevelopment potential for flats or trading area student accommodation (STP) SAVILLS SOUTHAMPTON 2 Charlotte Place Southampton, SO14 0TB +44 (0) 23 8071 3900 savills.co.uk Location Accommodation Clowns & Jesters is located in the Bevois Valley in Southampton city centre. The City lies 19 miles north AREA SQ M SQ FT west of Portsmouth and 25 miles east of Bournemouth. Lower ground 274.43 2,954 Southampton is one of the south’s liveliest and most Ground 438.69 4,722 dynamic cities which benefits from good transport links throughout the UK by road, rail, air and sea. The First 159.75 1,720 University of Southampton, Solent University and TOTAL 872.87 9,396 campuses accommodate large numbers of students (c.31,000) in addition to office and residential population. Vacant Possession The property is prominently located on Bevois Valley The property is available with vacant possession. It Road, a popular student circuit in the city. Portswood currently operates as a separate wine bar and nightclub. Road is located 0.5 miles to the north, with operators such as 7 Bone Burgers, Loungers & Coffee #1. The property is located equidistant between the 2 Licences Southampton Universities and their campuses. -

Montana Liquor

[email protected] 406-494-0100 Endorsed by the Vol. 23, Number 6 A Tash Communications Publication May 2018 VGM revenues fall Gaming industry can’t get going By Paul Tash try has been compounded when consider - Montana Tavern Times ing that expenses have continued to rise. The state's gaming business continues All in all, not a pretty picture for to struggle, as revenues fell slightly in the gaming businesses in Montana. third quarter of Fiscal Year 2018 from the However, gaming operators and oth - same period a year ago, according to pre - ers in the hospitality industry are liminary figures recently released by the working to improve the economic Gambling Control Division. outlook, industry representa - Third quarter, which ended March 31, tives said. registered a total of $15 million in revenues "Like many Montana from video gaming machines (VGM), small businesses, our gam - down about 1 percent from 3Q FY17, ing operators face signifi - which totaled about $15.1 million. VGM cant challenges in this revenues have flatlined in the last four economy," said John years – with third quarter totals registering Iverson, government affairs $15.2 million in 2016 and $15.1 million in counsel and lobbyist for the 2015. And the five years before that, the Montana Tavern Association. industry was working its way out of a "However, they’re resilient and recession, which dumped 2010 and ‘11 rev - will continue to work hard to enues down to the $12 million mark (see grow the market amidst these accompanying chart). challenges." Tax revenues remain about 6 percent “Flat VGM tax revenues behind the industry’s high mark of $16 mil - underscore the challenges lion recorded in the second quarter of faced by many small business - FY08. -

City of Denton Restaurant and Bar Occupancy Totals

City of Denton Restaurant and Bar Occupancy Totals Information updated as of 05‐04‐20 Occupancy totals are for customers only and do not include employees. This list is dynamic with data coming from multiple sources. As occupancy totals are confirmed, data for additional establishments will be added. 25% Occupancy ‐ Maximum Allowed on May 1 Under GA‐18 50% Occupancy Physical Address Establishment Name Total Occupancy* (Rounded Down) * (Rounded Down)* Permit Type 1000 AVENUE C 299 ORIENTAL EXPRESS 33 8 16 Restaurant 219 W OAK ST 940'S KITCHEN & COCKTAILS 98 24 49 Restaurant 3220 TOWN CENTER TRL ALAMO DRAFTHOUSE (RESTAURANT AND PATIO) 175 4387Restaurant 208 E MCKINNEY ST SUITE A AMBROSIO TACOS 37 9 18 Restaurant 2600 PANHANDLE DR ANDY B'S ENTERTAINMENT 891 222 445 Restaurant 707 S I‐35E APPLEBEE'S 198 49 99 Restaurant 901 W UNIVERSITY ARBY'S 102 25 51 Restaurant 2313 COLORADO BLVD ARBY'S 99 24 49 Restaurant 105 W HICKORY ATOMIC CANDY 19 4 9 Restaurant 2201 S I‐35E P3 AUNTIE ANNES STORE (employees) 9 2 4 Restaurant 1125 E UNIVERSITY DR 105 BAGHERI'S RESTAURANT 85 21 42 Restaurant 100 W OAK ST # 150 & 16 BARLEY AND BOARD 191 47 95 Restaurant 2201 I35E SOUTH NO1A BARNES & NOBLE BOOKSTORE CAFÉ 49 12 24 Restaurant 2900 WIND RIVER 148 BETH MARIE'S ICE CREAM 44 11 22 Restaurant 220 W PARKWAY ST 100 BIG FATTY'S SPANKING SHACK 30 7 15 Restaurant 3250 S I‐35E BJ 'S BREWHOUSE 291 72 145 Restaurant 2900 WIND RIVER LN 142 BLUE GINGER ASIAN BISTRO 65 16 32 Restaurant 207 S BELL AVE BOCA 31 62 15 31 Restaurant 407 W UNIVERSITY BOOMER JACK WINGS #8 67 16 33 Restaurant 529 I35E SOUTH BRAUM'S 99 24 49 Restaurant 2922 W UNIVERSITY DR BRAUMS No. -

Florida Restaurant & Lodging Show and Healthy Food Expo Florida

Florida Restaurant & Lodging Show and Healthy Food Expo Florida 2019 Sample Attendee List by Establishment Type Bar, Nightclub, Lounge ABE'S PLACE TAP & GRILL EOLA WINE COMPANY REDS WINE AND CHEESE BAR KINDAS FRONT PAGE BREWING COMPANY ROQUE PUB BEACH BUCKET BAR & GRILL HAMMERHEAD BEACH BAR ROSEN RESORT BAR BLUE MARTINI HATFIELDS BAR AND GRILL SIGGYS AMERICAN BAR BOOTS & BOTTLES ICEBAR ORLANDO SUNSET VISTAS CAFE & BEACH BAR BRINY IRISH PUB IRON AXE BAR & GRILL TAP THIS BUBBA'S ROADHOUSE & SALOON JACQUES SPORTS BAR THE WICKED POUR DA CONCH BAR KEY WEST BAR TWO BUKS DELIGHTED PINA COLADA KINGS HEAD BRITISH PUB EMERALD GOAT IRISH PUB MIGUELO'S CAFE AND BAR Coffee Bar/Ice Cream Shop ASPEN COFFEE CO, CRUMBLES MYSTIC ICE CREAM BLESSED CUP LLC DA-BENCHI OSSORIO BAKERY BUBBLEOLOGY BOCA GUSTARE FOODS, LLC PERKS CAFE CAFE CORNER HOUSE OF LEAF & BEAN PRESS & GRIND CAFE CHAKRA BREW LLC DBA GROUND UP ICE CREAM EXPRESS PRESS CREAMERY CHILLIN OUT ICE CREAM KALEISIA TEA LOUNGE RECANZONE BEVERAGES CHOCOLATE CREATIONS TC INC LARRY'S OLD FASHION ICE CREAM RICHARDS COFFEE CHOCOLATE KINGDOM LATIDOS CAFE RIVERVIEW COFFEE, TEA AND BOOKS COFFEE DISTRICT LETS FIESTA LLC ROYAL SCOOP HOMEMADE ICE CREAM COFFEE GRIND INC LICKITY SPLITS ICE CREAM SCOOPS OLD FASHIONED ICE CREAM **Based on 2019 post-show data Florida Restaurant & Lodging Show and Healthy Food Expo Florida 2019 Sample Attendee List by Establishment Type SHIRLEYS ICE CREAM TAPILICIOUS TOPPER'S CRAFT CREAMERY SMALL BATCH CREAMERY TELLERS TREND TEA LLC SWEET SNOW AND TEA THE GREENERY CREAMERY VANTAGE POINT