642 / Theatre Journal TORNADO SEASON. by Emily K. Harrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moore, Oklahoma—Growth Cushions Tornado Impact

Cover Story Moore, Oklahoma—Growth COVER STORY Cushions Tornado Impact By Sandra Patterson photo courtesy City of Moore Economic Development Department oore, Oklahoma, is a city on the fast track of growth. Straddling I-35 and just 10 miles from Mdowntown Oklahoma City and 8 miles from Norman, home of the University of Oklahoma, Moore is a bedroom community experiencing an unprecedented surge in new home construction and an accompanying growth in retail development. According to Moore’s Economic Development Author- ity, more than 826 new home permits were issued in 2005 and commercial construction was valued at more than $16 million. The commission reports that the town’s assessed valuation has increased an average of 10 percent per year since 2001 to over $200 million in 2005. With a population of 18,781 in 1970, the city had grown to 41,138 by the 2000 census. It is expected to top 49,000 in 2006. Moore is also located in that part of the country known as Tornado Alley. And, of all the tornado-prone areas that comprise Tornado Alley, Moore is situated in one of Figure 1. Path of 1998 tornado (Map from National Weather Service the two that experiences the highest tornado count per Web site) square mile. Six Years, Three Tornadoes Since 1998, three tornadoes have torn through Moore. On October 4, 1998, a tornado struck the southwest side of the city (figure 1). With only F1 strength (see page 9 sidebar on the Fujita Scale), the damage was limited to ripped up vegetation, downed property fences, and torn roof shingles. -

FEMA Tornadoes Fact Sheet

adoes Torn Tornadoes are nature’s most violent storms. They come from powerful thunderstorms. They appear as a funnel- or cone-shaped cloud with winds that can reach up to 300 miles per hour. They cause damage when they touch down on the ground. They can damage an area one mile wide and 50 miles long. Before tornadoes hit, the wind may die down, and the air may become very still. They may also strike quickly, with little or no warning. Am I at risk? Fact Check 1. Where is the safest place in a home? Tornadoes are most common between March and August, but they can occur at any time. They 2. True or False? If you see a funnel cloud, seek can happen anywhere but are shelter immediately. most common in Arkansas, Iowa, 3. Which of the following weather signs mean a Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, tornado may be approaching? Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, a. A dark or green-colored sky. Oklahoma, South Dakota, and b. A large, dark, low-lying cloud. Texas - an area commonly called c. A rainbow. “Tornado Alley.” They are also d. Large hail. more likely to occur between 3pm e. A loud roar that sounds like a freight train. and 9pm but can occur at any time. All except for C (a rainbow) can be signs for a tornado. a for signs be can rainbow) (a C for except All (3) unpredictable and can move in any direction. any in move can and unpredictable True! Do not watch it or try to outrun it. -

A Background Investigation of Tornado Activity Across the Southern Cumberland Plateau Terrain System of Northeastern Alabama

DECEMBER 2018 L Y Z A A N D K N U P P 4261 A Background Investigation of Tornado Activity across the Southern Cumberland Plateau Terrain System of Northeastern Alabama ANTHONY W. LYZA AND KEVIN R. KNUPP Department of Atmospheric Science, Severe Weather Institute–Radar and Lightning Laboratories, Downloaded from http://journals.ametsoc.org/mwr/article-pdf/146/12/4261/4367919/mwr-d-18-0300_1.pdf by NOAA Central Library user on 29 July 2020 University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama (Manuscript received 23 August 2018, in final form 5 October 2018) ABSTRACT The effects of terrain on tornadoes are poorly understood. Efforts to understand terrain effects on tornadoes have been limited in scope, typically examining a small number of cases with limited observa- tions or idealized numerical simulations. This study evaluates an apparent tornado activity maximum across the Sand Mountain and Lookout Mountain plateaus of northeastern Alabama. These plateaus, separated by the narrow Wills Valley, span ;5000 km2 and were impacted by 79 tornadoes from 1992 to 2016. This area represents a relative regional statistical maximum in tornadogenesis, with a particular tendency for tornadogenesis on the northwestern side of Sand Mountain. This exploratory paper investigates storm behavior and possible physical explanations for this density of tornadogenesis events and tornadoes. Long-term surface observation datasets indicate that surface winds tend to be stronger and more backed atop Sand Mountain than over the adjacent Tennessee Valley, potentially indicative of changes in the low-level wind profile supportive to storm rotation. The surface data additionally indicate potentially lower lifting condensation levels over the plateaus versus the adjacent valleys, an attribute previously shown to be favorable for tornadogenesis. -

Explaining the Trends and Variability in the United States Tornado Records

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Explaining the trends and variability in the United States tornado records using climate teleconnections and shifts in observational practices Niloufar Nouri1*, Naresh Devineni1,2*, Valerie Were2 & Reza Khanbilvardi1,2 The annual frequency of tornadoes during 1950–2018 across the major tornado-impacted states were examined and modeled using anthropogenic and large-scale climate covariates in a hierarchical Bayesian inference framework. Anthropogenic factors include increases in population density and better detection systems since the mid-1990s. Large-scale climate variables include El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Pacifc Decadal Oscillation (PDO), Arctic Oscillation (AO), and Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO). The model provides a robust way of estimating the response coefcients by considering pooling of information across groups of states that belong to Tornado Alley, Dixie Alley, and Other States, thereby reducing their uncertainty. The infuence of the anthropogenic factors and the large-scale climate variables are modeled in a nested framework to unravel secular trend from cyclical variability. Population density explains the long-term trend in Dixie Alley. The step-increase induced due to the installation of the Doppler Radar systems explains the long-term trend in Tornado Alley. NAO and the interplay between NAO and ENSO explained the interannual to multi-decadal variability in Tornado Alley. PDO and AMO are also contributing to this multi-time scale variability. SOI and AO explain the cyclical variability in Dixie Alley. This improved understanding of the variability and trends in tornadoes should be of immense value to public planners, businesses, and insurance-based risk management agencies. -

MHMP 2014 UPDATE PART 3 I Ab Natural Weather Hazards

Severe Winds Non-tornadic winds of 58 miles per hour or greater. Hazard Description Severe winds, or straight-line winds, sometimes occur during severe thunderstorms and other weather systems, and can be very damaging to communities. Often, when straight-line winds occur, the presence of the forceful winds, with velocities over 58 mph, may be confused with a tornado occurrence. Severe winds have the potential to cause loss of life from breaking and falling trees, property damage, and flying debris, but tend not to cause as many deaths as tornadoes do. However, the property damage from straight line winds can be more widespread than a tornado, usually affecting multiple counties at a time. In addition to property damage to buildings (especially less sturdy structures such as storage sheds, outbuildings, etc.), there is a risk for infrastructure damage from downed power lines due to falling limbs and trees. Large scale power failures, with hundreds of thousands of customers affected, are common during straight-line wind events. Hazard Analysis Another dangerous aspect of straight line winds is that they occur more frequently beyond the April to September time frame than is seen with the other thunderstorm hazards. It is not rare to see severe winds ravage parts of the state in October and November—some winter storm events in Michigan have produced wind-speeds of 60 and 70 miles per hour. Stark temperature contrasts seen in colliding air masses along swift-moving cold fronts can occur during practically any month. Figures from the National Weather Service indicate that severe winds occur more frequently in the southern-half of the Lower Peninsula than any other area of the state. -

THE TORNADO POSITION a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty

THE TORNADO POSITION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Eric Morris August, 2010 THE TORNADO POSITION Eric Morris Thesis Approved: Accepted: ________________________________ ________________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Chand K. Midha ________________________________ ________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Michael Dumanis Dr. George K. Newkome ________________________________ ________________________________ Faculty Reader Date Dr. Robert Miltner ________________________________ Department Chair Dr. Michael Schuldiner ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Epilogue ...............................................................................................................................v Erratum ................................................................................................................................1 Short Documentary Film......................................................................................................2 How to Assume the Tornado Position (1)............................................................................4 Once a Boy ...........................................................................................................................5 Siren Siren and now I’m Expected to Sleep ........................................................................7 When Used as Directed, the Tornado Position -

Tornado Risks and Hazards in the Southeastern United States

Tornado Risks and Hazards in the Southeastern United States TORNADO RECOVERY ADVISORY RA1, June 2011 Purpose and Intended Audience The purpose of this Tornado Recovery Advisory is to provide background on the tornado hazard in the Southeast. The general population, homeowners and renters, policy makers, local officials, builders, and building departments should understand that tornado occurrence in the Southeast is not a rare event. In fact, of the top 20 States in tornado frequency, 5 are in the Southeast. This advisory also identifies FEMA resources that can be used to help design and construct portions of almost any building type (including residences) to provide safe refuge from tornadoes, or to help minimize damage caused by these wind events. This Recovery Advisory Addresses: The National Weather Service uses the " Recent events Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF Scale) to categorize " Tornado occurrence outside “Tornado Alley”… tornado severity based on observed damage. how great is the risk? The scale ranges from EF0 to EF5. See http://www.spc.noaa.gov/efscale for further " Assessing your risk information on the EF Scale. " Can a building survive a tornado? Yes! EF Scale 3-Second Gust Speed (mph) " Weather radios EF0 65–85 Recent Events EF1 86–110 EF2 111–135 In the late afternoon of April 27, 2011, a large EF3 136–165 outbreak of tornadoes struck Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, and portions of Georgia. The EF4 166–200 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration EF5 Over 200 (NOAA) estimated there were approximately 190 tornadoes that touched down between 8:00 a.m. EDT April 27 and 8:00 a.m. -

Tornadoes Activity

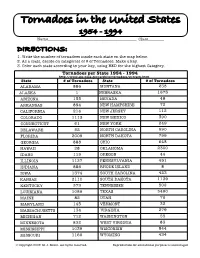

Tornadoes in the United States 1954 - 1994 Name_____________________________________________ Class________ DIRECTIONS: 1. Write the number of tornadoes inside each state on the map below. 2. As a class, decide on categories of # of Tornadoes. Make a key. 3. Color each state according to your key, using RED for the highest Category. Tornadoes per State 1954 - 1994 http://www.spc.noaa.gov/archive/tornadoes/st-trank.html State # of Tornadoes State # of Tornadoes ALABAMA 886 MONTANA 238 ALASKA 1 NEBRASKA 1673 ARIZONA 155 NEVADA 48 ARKANSAS 854 NEW HAMPSHIRE 72 CALIFORNIA 214 NEW JERSEY 112 COLORADO 1113 NEW MEXICO 390 CONNECTICUT 61 NEW YORK 249 DELAWARE 52 NORTH CAROLINA 590 FLORIDA 2009 NORTH DAKOTA 799 GEORGIA 888 OHIO 648 HAWAII 28 OKLAHOMA 2300 IDAHO 115 OREGON 44 ILLINOIS 1137 PENNSYLVANIA 451 INDIANA 886 RHODE ISLAND 8 IOWA 1374 SOUTH CAROLINA 423 KANSAS 2110 SOUTH DAKOTA 1139 KENTUCKY 373 TENNESSEE 502 LOUISIANA 1086 TEXAS 5490 MAINE 82 UTAH 76 MARYLAND 145 VERMONT 32 MASSACHUSETTS 134 VIRGINIA 279 MICHIGAN 712 WASHINGTON 55 MINNESOTA 832 WEST VIRGINIA 83 MISSISSIPPI 1039 WISCONSIN 844 MISSOURI 1166 WYOMING 434 © Copyright 2009 M. J. Krech. All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational purposes is encouraged. United States Tornado Hazard Map © Copyright 2009 M. J. Krech. All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational purposes is encouraged. SUMMARY QUESTIONS: 1. Which state(s) had the highest number of tornadoes during this time period? 2. Which state had the lowest number of tornadoes during this time period? 3. What states would you consider to be part of what is called, “Tornado Alley?” 4. Is our state part of Tornado Alley? ___________ 5. -

TORNADOES a Midwestern Boyhood by David Foster Wallace

M E M 0 R TENNIS, TRIGONOMETR~ TORNADOES A Midwestern boyhood By David Foster Wallace . '~en I left the boxed township of Between the ages of twelve and fif- truer than most girls my age. What I Illinoisfarmland where I grew up to at- teen I was a near great junior tennis could do-in the words of my town- tend my dad's alma mater in the lurid, player. I cut my competitive teeth ship's juniors' coach, a thin guy who jutting Berkshires of western Mas- beating up on lawyers' and dentists' chewed Red Man and spat into a Fol- sachusetts, I right away developed a kids at little Champaign and Urbana gers can-was "Play the Whole jones for mathematics. I'm starting to country club events, and was soon Court." This was a tennis cliche that see why this was so. College math killing whole summers being driven could mean any number of things. In evokes a Midwesterner's sickness for through dawns to tournaments all over my case, it meant I knew my limita- home. I'd grown up inside vectors, Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa. At four- tions and the limitations of the courts lines and lines athwart lines, grids- teen I was ranked seventeenth in the I played on, and adjusted thusly. I was and, on the scale of horizons, broad United States Tennis Association's at my best in bad conditions. curving lines of geographic force, the Western Section ("Western" being Now, conditions in Central Illinois weird topographical drain-swirl of a the creakily ancient USTA's designa- are from a mathematical perspective whole lotof ice-ironed flatland that tion for the Midwest;farther west were interesting and from a tennis point of sits and spins atop plates. -

3291248.PDF (7.836Mb)

T h e Un i v e r s i t y o f O k l a h o m a G r a d u a t e C o l l e g e WARNING RECEPTION, RESPONSE, AND RISK BEHAVIOR IN THE 3 MAY 1999 OKLAHOMA CITY LONG-TRACK VIOLENT TORNADO A D issertation S u b m it t e d t o t h e G r a d u a t e F a c u l t y in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of D o c t o r o f P h i l o s o p h y By M a t t h e w D a v i d B id d l e Norman, Oklahoma 2007 UMI Number: 3291248 UMJ UMI Microform 3291248 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 WARNING RECEPTION, RESPONSE, AND RISK BEHAVIOR IN THE 3 MAY 1999 OKLAHOMA CITY LONG-TRACK VIOLENT TORNADO A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY BY J. Scott Greene - Chair M ark Meo Karl H. Offen T. H. Lee Williams Charles A. Doswell III © Copyright by Matthew David Biddle 2007 All Rights Reserved. D e d i c a t i o n This work is dedicated to the victims of the tornadoes of 3 May 1999, their families, the first responders, the weather service personnel, and all that were touched by the forces of Mother Nature that fateful Monday evening. -

Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA

Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA WHITE PAPER PREPARED FOR THE U.S. GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH PROGRAM NATIONAL CLIMATE ASSESSMENT MIDWEST TECHNICAL INPUT REPORT Jeff Andresen1,2, Steve Hilberg3, and Ken Kunkel4 1 Michigan State Climatologist 2 Michigan State University 3 Midwest Regional Climate Center 4 Desert Research Institute Recommended Citation: Andresen, J., S. Hilberg, K. Kunkel, 2012: Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA. In: U.S. National Climate Assessment Midwest Technical Input Report. J. Winkler, J. Andresen, J. Hatfield, D. Bidwell, and D. Brown, coordinators. Available from the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments (GLISA) Center, http://glisa.msu.edu/docs/NCA/MTIT_Historical.pdf. At the request of the U.S. Global Change Research Program, the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Center (GLISA) and the National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment formed a Midwest regional team to provide technical input to the National Climate Assessment (NCA). In March 2012, the team submitted their report to the NCA Development and Advisory Committee. This white paper is one chapter from the report, focusing on potential impacts, vulnerabilities, and adaptation options to climate variability and change for the historical climate sector. U.S. National Climate Assessment: Midwest Technical Input Report: Historical Climate Sector White Paper Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

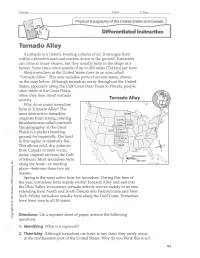

Tornado Alley a Tornado Is a Violent, Twisting Column of Air

Name ___________________ Date ____ Class _____ Physical Geography of the United States and Canada DiHerentiated Instruction Tornado Alley A tornado is a violent, twisting column of air. It emerges from within a thundercloud and reaches down to the ground. Tornadoes can come in many shapes, but they usually form in the shape of a funnel. Some have wind speeds of up to 450 miles (724 km) per hour. Most tornadoes in the United States form in an area called "Tornado Alley." This area includes parts of several states, shown on the map below. Although tornadoes occur throughout the United States, especially along the Gulf Coast from Texas to Florida, people often think of the Great Plains when they hear about tornado activity. Tornado Alley Why do so many tornadoes form in Tornado Alley? The most destructive tornadoes originate from strong, rotating thunderstorms called supercells. The geography of the Great Plains is a perfect breeding ground for supercells. The land in this region is relatively flat. This allows cold, dry, polar air from Canada to meet warm, moist, tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico. Most tornadoes form 400 miles along the front-or meeting place-between these two air masses. Spring is the most active time for tornadoes. During this time of the year, tornadoes form mainly within Tornado Alley and east into the Ohio Valley. In summer, tornado activity moves mainly to an area extending from North and South Dakota into Pennsylvania and New York. Winter tornadoes usually form along the Gulf Coast. Tornadoes have been seen in alISO states.