Great Bay National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Marsh Hazard Atlas & Project Compendium

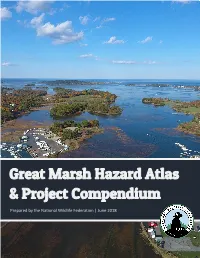

Great Marsh Hazard Atlas & Project Compendium Prepared by the National Wildlife Federation | June 2018 Great Marsh Hazard Atlas & Project Compendium June 2018 Prepared for: Town of Essex, Massachusetts 30 Martin Street Essex, MA 01929 and Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management 251 Causeway Street, Suite 800 Boston, MA 02114-2136 Prepared by: National Wildlife Federation 11100 Wildlife Center Drive Reston, VA 20190 This document was produced with funding provided by the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management through their Coastal Community Resilience Grant Program. Cover photo © Abby Manzi/DeRosa Environmental Consulting, Inc. www.nwf.org Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Hazard Atlas .............................................................................................................................................. 1 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................ 2 BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................................... 3 Birds ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Shellfish ................................................................................................................................................ -

Adaptation Strategies for the Great Marsh Region

Ranger Poole/USFWS CHAPTER 4 Adaptation Strategies for the Great Marsh Region Assessing vulnerability is the first step in generating adaptation options to increase resilience and reduce vulnerability. Understanding why an asset is vulnerable is especially critical to thinking about adaptation and in particular, identifying adaptation options that can address one or more of the three components of vulnerability (i.e. exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity). Furthermore, while vulnerability assessments provide the context necessary for identifying important issues to consider when designing adaptation strategies, the identification of “key vulnerabilities” can help steer the generation of adaptation options in a direction that focuses on the most critical issues. 376 This chapter outlines a range of adaptation strategies identified through the Community Adaptation Planning Process (see Chapter 2). The following strategies and recommendations are broken into two categories: regional strategies and town-specific strategies. Successful short and long-term implementation of all of these recommendations will require an extensive amount of intra- and inter- municipal cooperation, regional collaboration, and ongoing environmental research and monitoring. The Great Marsh Region is fortunate to have a wide diversity of organizations, agencies, and municipalities working to protect and restore the Great Marsh. However, these efforts will need to be continually strengthened to achieve the degree of change and level of project implementation recommended in this report. 376 Stein, B.A., P. Glick, N. Edelson, and A. Staudt (eds.), Climate-Smart Conservation: Putting Adaptation Principles into Practice (Reston, VA: National Wildlife Federation, 2014), 120 Ch 4. Adaptation Strategies for the Great Marsh Region | 124 4.1 Regional Strategies and Recommendations This section highlights adaptation strategies that should be adopted to reduce vulnerability on a regional scale. -

Essex County's Spectacular Great Salt Marsh

ESSEX COUNTY’S SPECTACULAR GREAT SALT MARSH LECTURE TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Doug Stewart Date: February 6, 2016 Runtime: 51:45 Identification: AL01 ; Audio Lecture #01 Citation: Stewart, Doug. “Essex County’s Spectacular Great Salt Marsh”. CAM Video Lecture Series, February 6, 2016. AL01, Cape Ann MuseuM Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for perMission to publish Material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Description, Finding Aid: Victoria Petway, April 29, 2020. Subject Lists: Anne Siegel, November 9, 2020. Description An audio recording at the Cape Ann MuseuM in Gloucester, MA of the February 6, 2016 program by lecturer and freelance Magazine writer Doug Stewart presenting an illustrated lecture on Essex County’s spectacular Great Salt Marsh. The Marsh stretches from Cape Ann to New Hampshire and is a biological engine whose nutrients sustain fish stocks and bird life. It also protects shore towns from flooding and storm surges, but despite its necessity, the Marsh is poorly understood and under-appreciated. Stewart will explore the Great Marsh’s past Essex County’s Spectacular Great Salt Marsh – AL01 – page 2 as valuable real estate for farMing salt hay, its uniQue success over Much of the past century in dodging the nation’s swaMp-filling Mania, and its uncertain future as sea-level rise accelerates. Photographs by Dorothy Kerper Monnelly of the Great Salt Marsh were on view during the lecture. Transcript Kate LaChance 0:00 Good afternoon, everyone. My naMe is Kate LaChance. I'M the PrograM Coordinator here at the Cape Ann MuseuM. First things first, this turnout is amazing. -

Parker River/Essex Bay ACEC Resource Inventory

Parker River/Essex Bay ACEC Resource Inventory TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................3 ACEC CHARACTERISTICS AND DESIGNATION.............................................................................5 PLUM ISLAND SOUND .........................................................................................................................8 ESSEX BAY .............................................................................................................................................8 GEOLOGY AND SOILS..........................................................................................................................10 WATERSHED CHARACTERISTICS ..................................................................................................12 HABITATS OF THE ACEC ....................................................................................................................14 BARRIER BEACH .................................................................................................................................14 ESTUARINE WATERS .........................................................................................................................14 Plum Island Sound ..............................................................................................................................14 Essex Bay.............................................................................................................................................16 -

Traditional Uses of the Great Marsh a Review of Lesser-Known Resources in Massachusetts’ Great Salt Marsh

TRADITIONAL USES OF THE GREAT MARSH A REVIEW OF LESSER-KNOWN RESOURCES IN MASSACHUSETTS’ GREAT SALT MARSH Elisabeth Holden | Janna Newman | Ian Thistle | Eliza Davenport Whiteman Tufts University | Urban + Environmental Policy + Planning | Spring 2013 Acknowledgments Team Great Marsh would like to extend its appreciation to all those who made this project possible. We would especially like to thank Peter Phippen, Deborah Carey and the whole Eight Towns & the Great Marsh Com- mittee for their input and guidance. This project would not have been possible without the voices and expertise of our interviewees. We are incredibly grateful to Jim Cunningham, Wayne David, Bethany Groff of Historic New England, Robert Buchsbaum of Mass Audubon, Nancy Pau of Parker River Wildlife Refuge, Jim Sargent of the Town of Gloucester, and Wayne Castanguay of the Ipswich River Watershed Association for sharing their time and knowledge. We would also like to thank the UEP Field Projects teaching team for their patience, advice and dedication. We are particularly grateful to Professor Rusty Russell and Teaching Assistant Kaitlin Kelly. Finally, a special thank you to UEP Professor Rachel Bratt for the use of her office. 3 Abstract This report was created by a project team of graduate students from the Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Department at Tufts University, in conjunction with a non-profit client, the Eight Towns and the Great Marsh Committee. The Great Marsh, a 20,000-acre salt marsh in northeastern Massachusetts, is a crucial habitat for birds and aquatic species. For as long as humans have populated the area, residents have depended on the Marsh and the ocean for sustenance and livelihood. -

Great Outdoors Table of Contents

Essex National Heritage Area Guide to the Great Outdoors Table of Contents Walks & Rambles.......................2 Bring the Kids............................5 Wildlife Preserves......................7 Historic Routes...........................10 Scenic Farms...............................13 Vistas............................................15 Wooded Landscapes..................18 Beaches & Marshes....................20 Urban Parks & Reservations.....23 Lakes, Ponds & Rivers...............25 Woodsom Farm Salisbury Point Ghost Trail 12 Locations on map are approximate. 29 50 Lake Attitash State Boat Ramp Old Eastern Marsh Trail 51 36 18 Maudslay State Park Salisbury Beach State Reservation Tattersall Farm 14 33 Parker River NWR, Lot 1 Parker River National Old Town Hill Wildlife Refuge 3 8 37 38 Veasey Sawyers Island Memorial Park Rowley Town Ramp 35 Choate (Hog) Island Stevens-Coolidge Harlan P. Kelsey Arboretum Greenwood Farm Place 22 10 46 Ipswich Town Landing Halibut Point State Park Den Rock Park 47 20 Crane Wildlife Refuge Deer Jump Reservation 32 15 25 Boxford State Forest/ Hood Pond 6 28 Hamlin Reservation 26 27 Bald Hill Reservation Appleton Farms Weir Hil 11 34 13 Granite, Pier, Willowdale Goose Cove State Forest Essex Town Landing Wharf Road Appleton Farms 30 Reservation Harold Parker State Forest 49 5 2 19 Grass Rides 44 Bradley Palmer 21 Cox Reservation 1 Dogtown 17 Ward Reservation State Park Goldsmith Woodlands 9 7 Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary Ravenswood Park 4 Eastern Point Long Hill 41 45 Pavilion Beach 31 48 39 Glen -

Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Restoration Compendium

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and PREP Reports & Publications Space (EOS) 2008 Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Restoration Compendium Alyson L. Eberhardt University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] David M. Burdick University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/prep Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Eberhardt, Alyson L. and Burdick, David M., "Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Restoration Compendium" (2008). PREP Reports & Publications. 76. https://scholars.unh.edu/prep/76 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in PREP Reports & Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Habitat Restoration Compendium Alyson L. Eberhardt and David M. Burdick University of New Hampshire This project was funded by the NOAA Restoration Center in conjunction with the Coastal Zone Management Act by NOAA’s Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management in conjunction with the New Hampshire Coastal Program and US Environmental Protection Agency’s National Estuary Program through an agreement with the University of New Hampshire Hampton-Seabrook Estuary -

An Innovative Approach to Restoration in the Great Marsh

An Innovative Approach to Restoration in the Great Marsh (1) Holistic and Integrated Restoration to improve the resiliency of the Great Marsh • Beaches and Dunes, High Marsh, Low Marsh, Subtidal, Tidal Creeks and Channels, Rivers and Watersheds, and in Town Hall (2) Hands-on project management team: the Great Marsh Resiliency Partnership • Partners working together with project leads and many sub-teams Background: • The Great Marsh is a relatively intact and healthy marsh ecosystem • There are signs of degradation due to anthropogenic activities • Climate Change and Sea Level Rise will exacerbate the decline of the Great Marsh if not addressed Great Marsh Resiliency Partnership Mission: To preserve, protect, restore, and enhance the Great Marsh through actions that create coastal resiliency Great Marsh’ North Shore Massachusetts Boston Great Marsh Salt Marsh Partners: Massachusetts Bays National Estuary Program, Eight Towns and Great Marsh Committee, Merrimack Valley Planning Commission, Ipswich River Watershed Association, MA Audubon Society, Green Crab R&D, Boston University, University of New Hampshire, the Towns of the Great Marsh, National Wildlife Federation, Massachusetts Environmental State Agencies, federal agencies, and many others Great Marsh Resiliency • The Great Marsh is the largest contiguous salt marsh in New England, 25,000 acres of Beaches and Dunes, Salt Marsh, Subtidal Flats, Creeks and Great Marsh Channels NH to Cape Ann • A healthy, resilient Great Marsh provides abundant natural habitat for important wildlife species, -

EVALUATION and MANAGEMENT in the UPPER GREAT MARSH: Emergent Phragmites Australis

EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT IN THE UPPER GREAT MARSH: Emergent Phragmites australis EME Source: Massachusetts Audubon Society RGENT PHRAGMITES AUSTRALIS: EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT IN THE UP PREPARED FOR: EIGHT TOWNS & THE BAY/MERRIMACK VALLEY PLANNING COMMISSION PROVIDED BY: JENNA RINGELHEIM GINA FILOSA LAUREN BAUMANN JAY ASTLE TUFTS UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND PLANNING MAY 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the many people that shared their knowledge and expertise with us through the course of this project. Peter Phippen - Eight Towns and the Bay John Larsen, Molly Mead, Rusty Russell, and Kelley Whitmore – Tufts University Barbara Blumeris and Mike Tuttle – Army Corps of Engineers Jay Baker, Bruce Carlisle, and Hunt Durey – Coastal Zone Management Paul Capotosto – Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, Wildlife Division Geoff Walker – Ducks Unlimited Tim Purinton and Robert Buchsbaum – Massachusetts Audubon Society Jim Straub – Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Susan Antenen, Karen Lombard, and Jess Murray – The Nature Conservancy Jack Card, Jr. – Northeast Mosquito Control and Wetlands Management District Geoff Wilson – Northeast Wetlands Restoration Frank Drauszewski and Janet Kennedy – Parker River Wildlife Refuge While we received much assistance in the preparation of this report, any errors, omissions, or mischaracterizations remain the sole responsibility of the authors. This report is the result of a joint project administered by the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning at Tufts University and Eight Towns and the Bay/Merrimack Valley Planning Commission. May 3, 2005 Jenna Ringelheim Gina Filosa Lauren Baumann Jay Astle TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………..……. 1 SECTION 1: THE PROJECT Project Summary………………………………………………………......... -

Patrick-Murray Administration Announces Completion of 33-Acre

For Immediate Release - June 09, 2010 Patrick-Murray Administration Announces Completion of 33-acre Salt Marsh Restoration Project in Newbury Project part of larger effort to enhance habitat in New England's largest salt marsh BOSTON - June 9, 2010 - In keeping with Governor Deval Patrick's support for habitat conservation, Department of Fish and Game (DFG) Commissioner Mary Griffin today announced the completion of a 33-acre salt marsh restoration project in the North Shore's Great Marsh. "Salt marshes are some of the most ecologically rich ecosystems on the planet and this project helps to protect this valuable natural resource," said Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) Secretary Ian Bowles. Salt marsh restoration projects protect commercial and recreational fisheries, help to stop the spread of invasive species and conserve wildlife habitat. Salt marshes protect against coastal storm surges and provide natural flood mitigation and water purification. The Newman Road Salt Marsh Restoration Project in Newbury was funded by a $1 million federal grant secured by the Essex County Greenbelt Association and the DFG's Division of Ecological Restoration from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA). The NAWCA program provides matching grants that support public-private partnerships involving long-term protection, restoration, and/or enhancement of wetlands and associated upland habitats for the benefit of migratory waterfowl. The grant provided $600,000 to protect a 70-acre coastal property in Essex and $400,000 to replace an undersized culvert under Newman Road. "The Great Marsh is a major shellfish and fin fish nursery and is a globally important foraging and resting area for migrating birds along the Atlantic flyway," said Commissioner Griffin.