Timing of Ornaments in the Theme from Beethoven's Paisiello Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Global Graphic Score Project Contents Introduction 2

A guide to the Global Graphic Score Project Contents Introduction 2 A guide to graphic scores 3 Composing a graphic score 5 Performing a graphic score 6 Global Graphic Score Project | School of Noise 1 Introduction What is it? The Global Graphic Score Project by the School of Noise (in partnership with Alexandra Palace) aims to bring together people from around the world using sound and art. Whatever your age, location or musical or artistic skill level, you are invited to take part in this worldwide experimental sound art collaboration. We would like to encourage people who have never met to be inspired by each other’s artwork to create new sounds and pieces of music. Together we can create a unique collection of beautiful graphic scores and experimental pieces of music. How does it work? • Individuals or groups of people design and upload their graphic scores. • People view the online gallery of graphic scores and select one to download. • These scores are performed and turned into music and sound art pieces. • Recordings are made and loaded to our website for other people to listen to. You can choose to be the composer or the performer. Or maybe try doing both! What next? The next few pages will explain what graphic scores are, provide you with ideas on how to make one, and suggest ways you can turn a graphic score into music. We hope that you have lots of fun creating and performing these graphic scores. Final notes This activity can take place anywhere and you don’t have to have real musical instruments available. -

ASSIGNMENT and DISSERTATION TIPS (Tagg's Tips)

ASSIGNMENT and DISSERTATION TIPS (Tagg’s Tips) Online version 5 (November 2003) The Table of Contents and Index have been excluded from this online version for three reasons: [1] no index is necessary when text can be searched by clicking the Adobe bin- oculars icon and typing in what you want to find; [2] this document is supplied with direct links to the start of every section and subsection (see Bookmarks tab, screen left); [3] you only need to access one file instead of three. This version does not differ substantially from version 4 (2001): only minor alterations, corrections and updates have been effectuated. Pages are renumbered and cross-refer- ences updated. This version is produced only for US ‘Letter’ size paper. To obtain a decent print-out on A4 paper, please follow the suggestions at http://tagg.org/infoformats.html#PDFPrinting 6 Philip Tagg— Dissertation and Assignment Tips (version 5, November 2003) Introduction (Online version 5, November 2003) Why this booklet? This text was originally written for students at the Institute of Popular Music at the Uni- versity of Liverpool. It has, however, been used by many outside that institution. The aim of this document is to address recurrent problems that many students seem to experience when writing essays and dissertations. Some parts of this text may initially seem quite formal, perhaps even trivial or pedantic. If you get that impression, please remember that communicative writing is not the same as writing down commu- nicative speech. When speaking, you use gesture, posture, facial expression, changes of volume and emphasis, as well as variations in speed of delivery, vocal timbre and inflexion, to com- municate meaning. -

Audition Preparation Tips Since We Do Not Know Which Group You Will Be

Audition Preparation Tips Since we do not know which group you will be placed in until you perform an audition during your first morning on campus, we are unable to send you the concert music in advance. There is a span of less than 48 hours from the first orchestral rehearsal on Friday, where you see the music for the first time, until the final concert on Sunday. Sight-reading skills are an important component of each group’s success. That is why we have changed the audition process to focus on and assess your ability to sight-read accurately. Sight-reading is a crucial skill which encompasses many aspects of your musicianship. It is valuable to develop the ability to quickly and accurately understand and assimilate the varied information indicated in musical notation including pitches, rhythms, tempos, dynamics and articulation. As with any audition, judges can also assess your technique, tone, intonation, and musicality through sight-reading. You may normally perform much more difficult music than the sight-reading excerpts you see on the stand for auditions. Of course the weeks and months of study and practice you have spent learning that difficult music, and the technical skills you have gained from that experience, will serve you well when you are sight-reading in your audition. You can practice sight-reading before the audition! The more you challenge yourself by playing music you have never seen before, the better you will get at sight-reading. Here are a few tips to help you practice this skill. Before beginning to play look over the music and take note of the following things: Time Signature (4/4, ¾, cut time etc.) Key Signature (how many sharps or flats) Dynamic indications (piano, forte, crescendo etc.) Tempo Indications (Allegro, Adagio, etc. -

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

User Manual ROCS Show|Ready User Manual © 2015 - Right on Cue Services

User Manual ROCS Show|Ready User Manual © 2015 - Right On Cue Services. All Rights Reserved Jonathan Pace, David McDougal, Dave McDougal Jr., Jameson McDougal, Andrew Pulley, Jeremy Showgren, Frank Davis, Chris Hales, John Schmidt, Woody Thrower Documentation written by Andrew Pulley. ROCS Show|Ready Build 1.2.5-build-42 REV A Right On Cue Services 4626 N 300 W - Suite 180 801-960-1111 [email protected] 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Show|Ready User Manual | III Contents 1 Downloading your Licensed Show 1 Upon Starting the Program . 1 Cast Authorization . 1 Director Authorization . 1 2 Introduction to Show|Ready 2 The Interface - Main Window . 2 Transport . 3 Temporary Editing . 4 Song List . 4 Timeline . 5 Marker List . 6 Mixer . 6 Change Log . 7 The Interface - Score View . 8 3 Navigation and Editing 9 Navigation . 9 Go to Bar . 9 Pre Roll . 9 Escape Vamps and Caesuras, and Jump with Fermatas . 9 Editing . 10 Timeline Selection . 10 Making Cuts and Adding Fermatas . 10 Vamps, Repeats, Transpositions, Markers, and Click Resolution . 11 Sending changes to the cast . 11 Returning to Previous Change Logs . 11 iv | Table of Contents High-Resolution Editing . 11 4 Keyboard Shortcuts 12 Mac . 12 Windows . 12 5 Frequently Asked Questions 13 Show|Ready User Manual | 1 Downloading your Licensed Show 1Thank you for using Show|Ready. We’ve worked the dialog box labeled, “Cast Member Authorization tirelessly for the past several years developing the Code,” and click, “Activate Show.” The show will then technology you are using today, and taken even more begin to download and open to the main window. -

University Musical Society Ivo Pogorelich

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY IVO POGORELICH Pianist Wednesday Evening, March 11, 1992, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Three Nocturnes .......... Chopin C minor, Op. 48, No. 1 E-flat major, Op. 55, No. 2 E major, Op. 62, No. 2 Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58 ... Chopin Allegro maestoso Scherzo: molto vivace Largo Finale: presto non tanto, agitato INTERMIS SION Valses nobles et sentimentales . Ravel I. Modere-tres franc II. Assez lent III. Modere IV. Assez anime V. Presque lent VI. Vif VII. Moins vif VIII. Epilogue: lent Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36 Rachmaninoff Allegro agitato Non allegro L'istesso tempo - Allegro molto Ivo Pogorelich plays the Steinway piano available through Hammell Music, Inc., Livonia. Ivo Pogorelich is represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. Activities of the University Musical Society are supported by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs and the National Endowment for the Arts. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. Thirty-first Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Three Nocturnes: Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58 C minor, Op. 48, No. 1 FREDERIC CHOPIN E-flat major, Op. 55, No. 2 he Sonata in B minor is the third and last of Chopin's piano sona E major, Op. 62, No. 2 tas. Composed in 1844, it is FREDERIC CHOPIN (1810-1849) approximately contemporaneous lthough the piano was over a with Chopin's three Mazurkas of century old by Chopin's time, Op.T 56, the Berceuse in D-flat, Op. -

Study Guid E

Year: 5 Subject: Music Unit of Study: Air Linked Literature: Lives of Musicians by Kathleen Krull / The Story of the Orchestra by Meredith Hamilton Rhythm—reading and India— Pitch—comparison Rhythm—composing Musical chronology Air composition notating Pulse and rhythm through songs within structures Vocabulary I need to know: I need to do: Prior knowledge/skills: Bristol is famous for its mastery of air—hot air balloons and Use voices and instruments to play Refers to the volume of a sound or Explore dynamics through singing, dynamics solo and ensemble with increasing note Concorde - so this unit celebrates that, alongside flight in nature. listening and performing music Through listening to songs and musical compositions, as well as sounds Explore pitch through listening, accuracy , fluency, control and pitch How high or low a note is expression in the environment, we are able to explore and identify the different graphic score study, composing and effects created by pitch, tempo and dynamics. Also, we can reflect on Begin to improvise and compose tempo Musical word for speed performing the feelings that these compositions evoke so that we can intentionally music compose pieces of music that suit the purpose for our work. To be able Explore tempo through listening, Listen with increasing attention to A method used to compose a discussion, conducting and singing graphic score piece of music without using com- to remember their compositions, composers use musical notations, music and recall sounds with mon music notation which can be the commonly recognised method (shown below) or Composing short pieces and noting increasing aural memory graphic score notation. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Fairfield Public Schools Music Department Curriculum Orchestra Skill Levels

Fairfield Public Schools Music Department Curriculum Orchestra Skill Levels ORCHESTRA SKILL LEVEL I (Grade 4) A. Executive Skills 1. Exhibits proper posture and playing position 2. Exhibits proper rehearsal and performance procedures in ensemble playing 3. Understands effective practice habits 4. Demonstrates proper care and safety of instrument 5. Demonstrates proper right hand position 6. Demonstrates proper left hand position 7. Identifies parts of the instrument B. Tone Quality Students should: 1. Draw a straight bow 2. Demonstrate proper contact point between bridge and fingerboard 3. Demonstrate even bow speed 4. Produce a characteristic sound on the instrument 5. Use appropriate articulation techniques. 6. Play dynamics C. Bowing Demonstrates the following bow strokes and articulations: 1. Detache (legato) 2. Staccato 3. Two-note slur, three-note slurs and ties 4. Bow lifts 5. Right hand pizzicato 6. Left hand pizzicato 7. Imitate bowing patterns D. RHythms and Note Reading Read and play music which includes the following: 1. Rhythms using quarter, half, dotted half, whole, pair of eighth notes and corresponding rests 2. Demonstrate the ability to recognize and perform various rhythm patterns. 3. Read music in the following Time Signatures: 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 4. Identify and Perform symbols and terms: Half note, Clef, Time signature, Bar line, Repeat sign, Up bow, Down bow, Whole note, Staff, Quarter note, Eighth notes, Key signature, Quarter rest, Half rest, Whole rest, Dotted half note, Bow lift, Measure, Tie, Slur, Plucking and Bowing E. Scales and Scale Patterns 1. Scales Violin Viola Cello Bass G MA 1 octave 1 octave 1 octave 1 octave D MA 1 octave 1 octave 1 octave 1 octave I, (II & III Positions I I I on G string) F. -

Notes, Rhythm, and Meter Notes

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music NOTES, RHYTHM, AND METER NOTES: Notes represent a duration or length of a sound. Notes consist of the head the stem and the flag or beam. note = head + stem + flag NOTE HEADS: The head of the note should be written as an oval (not a round circle) and should be centered on the line or space of the staff that represents the note. STEMS: Stems are notated on the right side of the note head and are ascending if the note head is on the 3rd line of the staff or below that line. Stems are notated on the left side of the note head and are descending if the note is on the 3rd line of the staff or above that line. Stems should be about 1 octave in length and should be straight up and down (not slanted). FLAGS: Flags are notated to the right of the stem whether the stem is on the right or left side of the note head. BEAMS: Notes should be beamed together to show the beat. Beams should therefore not cross beats. Beams should be straight lines, not curves. Beams may be slanted ascending or descending according to the contour of the notes. Beaming notes together may result in shortened or elongated stems on some notes. If beaming eighth notes and sixteenth notes together, sixteenth note beams should always go inside the beginning and ending stems. DURATIONS: Notes can have various durations and various names: American British (older version) double-whole breve whole semi-breve half minim quarter crotchet eighth quaver sixteenth semi-quaver thirty-second demi-semi-quaver sixty-fourth hemi-demi-semi-quaver These notes look like the following: double whole half quarter 8th 16th 32nd 64th whole In the above list, each note duration is one-half the duration of the preceding note duration. -

Standard Music Font Layout

SMuFL Standard Music Font Layout Version 0.5 (2013-07-12) Copyright © 2013 Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH Acknowledgements This document reproduces glyphs from the Bravura font, copyright © Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH. Bravura is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://www.smufl.org/fonts This document also reproduces glyphs from the Sagittal font, copyright © George Secor and David Keenan. Sagittal is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://sagittal.org This document also currently reproduces some glyphs from the Unicode 6.2 code chart for the Musical Symbols range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1D100.pdf). These glyphs are the copyright of their respective copyright holders, listed on the Unicode Consortium web site here: http://www.unicode.org/charts/fonts.html 2 Version history Version 0.1 (2013-01-31) § Initial version. Version 0.2 (2013-02-08) § Added Tick barline (U+E036). § Changed names of time signature, tuplet and figured bass digit glyphs to ensure that they are unique. § Add upside-down and reversed G, F and C clefs for canzicrans and inverted canons (U+E074–U+E078). § Added Time signature + (U+E08C) and Time signature fraction slash (U+E08D) glyphs. § Added Black diamond notehead (U+E0BC), White diamond notehead (U+E0BD), Half-filled diamond notehead (U+E0BE), Black circled notehead (U+E0BF), White circled notehead (U+E0C0) glyphs. § Added 256th and 512th note glyphs (U+E110–U+E113). § All symbols shown on combining stems now also exist as separate symbols. § Added reversed sharp, natural, double flat and inverted flat and double flat glyphs (U+E172–U+E176) for canzicrans and inverted canons. -

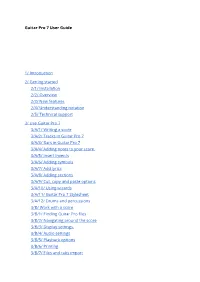

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window.