Diplomacy Defence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL COMBINED SENIORITY LIST of Asis (DISTRICT and PAP) AS PER CONFIRMATION

FINAL COMBINED SENIORITY LIST OF ASIs (DISTRICT AND PAP) AS PER CONFIRMATION Sr No. RANK, NAME & NO/ RANGE DOB DOE CASTE/ LIST C-I LIST C-II ACTUAL LIST D-I LIST D-II MERIT ACTUAL DATE OF ACTUAL DATE OF DATE OF DOP AS S.I REMARKS CATEGORY DOP AS HC NO. AS DOP AS ASI CONF AS CONF DATE LIST E LIST E-II (ACTUAL) P/ASI ASI OF ASI 1 DALBIR SINGH, 292/J BR 13-10-1944 14-06-1963 GC 20-08-1968 01-01-1971 01-09-1980 13-05-1982 01-01-1987 01-01-1987 01-04-1989 16-04-1992 RETD ON 31/10/2002 2 MOHINDER SINGH, 233/PR CP-LDH 29-10-1948 07-11-1969 SC 28-04-1973 19-11-1974 01-04-1982 27-11-1982 01-07-1988 01-07-1988 01-04-1989 14-05-1992 Retd/ on 31/10/06 3 SWARN DASS, 111/PR, 2/R PR 10-04-1951 29-07-1971 SC 02-11-1976 10-11-1976 27-11-1982 01-07-1988 01-07-1988 01-04-1989 14-05-1992 RETD ON 30/04/2009 4 DSP BALDEV SINGH 35/BR BR 16-03-1957 20-02-1976 JAT SIKH 18-12-1981 06-10-1986 05-10-1988 05-10-1988 01-01-1993 19-04-1993 5 SI MOHINDER SINGH 97/FR FR 11-12-1941 12-12-1960 RAMGARIHA 11-03-1971 05-06-1974 01-09-1983 10-11-1984 01-04-1989 06-09-1990 01-04-1991 20-03-1992 RETD ON 31.12.99 6 INSP PRITPAL SINGH PR/CP- 23-02-1964 09-04-1986 - - - - P/ASI 09-04-1986 21-04-1989 21-04-1989 01-10-1990 18-06-1991 266/PR LDH 7 RETD SI BAKHSHISH SINGH JR 01-12-1940 27-11-1962 GC 09-10-1968 02-05-1971 01-04-1982 09-01-1983 01-07-1989 01-07-1989 01-10-1991 28-04-1992 Died on 30.01.94 38/GSP 380/J 8 Insp Ram Singh NO. -

SIKH TIMES ALL PAGE for WEB.Qxd

@thesikhtimes facebook.com/ instagram.com/ thesikhtimes thesikhtimes VISIT: PUBLISHED FROM Delhi, Haryana, Uttar www.thesikhtimes.in Pradesh, Punjab, The Sikh Times Email:[email protected] Chandigarh, Himachal and Jammu National Daily Vol. 12 No. 219 RNI NO. DELENG/2008/25465 New Delhi, Tuesday, 29 December, 2020 [email protected] 9971359517 12 pages. 2/- Maharashtra home minister asks CBI to reveal findings of SSR Farmers' protest against death case probe Mumbai Maharashtra’s Home Minister Anil Deshmukh on Sunday said the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) should soon clarify whether late actor Sushant Singh agri laws enters day 33 Rajput was murdered or died by suicide. Speaking to members of the media, Deshmukh said, “It has been four months since the probe the protesting farmer was transferred to CBI. People ask me about the conclusion. I think CBI should soon unions had decided to clarify whether it was suicide or murder.” His comment comes months after the CBI was resume their dialogue handed over the investigation into the actor’s death earlier this year. Deshmukh has also with the Centre, and appealed to the agency to reveal findings of the probe in the high-profile case. In July, proposed December 29 almost a month after the actor's death, Deshmukh had said a CBI probe is not for the next round of required in the incident.It may be noted that talks. Simmi Kaur Babbar NEW DELHI: Farmers protest against the three central contentious agricultural laws entered day 33 on Monday (December 28) as the government and farmers' union leaders prepare for the sixth round of talks on Tuesday. -

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

W Akf Special

L A I C E P S F K A W www.thenews.co.in `50 Dear Readers, What we are bringing out is only a tip of the iceberg. A lot needs to be unearthed which re - quires a lot of time and painstaking efforts. The ‘Wakf Special’ contains a few stories which explain the deceitful tactics of the politi - cians - particularly the MIM and Congress lead - ers, corrupt officials of various government departments and the Wakf Board. During the course of collecting information under the Right to In - formation Act, it has been observed that the Wakf Board never both - ered to conduct real time survey of wakf properties based on the original records (Muntakabs), prepared during Nizam and Qutb Shahi regimes. The properties attached to masjids as shown in the current records of the Wakf Board had been prepared based on hearsay and The special issue is compiled by on the instructions of influential people including politicians and offi - MOULLIM MOHSIN BIN HUSSAIN cials resulting in huge loss to the Muslim community. AL KASARY, Journalist, Wakf Protection and Me and my family had to face severe hardships including false RTI Activist criminal cases, harassment by police and rejection by several people while working for the cause. But I believe in the Quranic verse, “Allah The News You Like has full knowledge of your enemies, and Allah is Sufficient as a Wali Phone: 9701141377, 9848133363 (Protector), and Allah is Sufficient as a Helper.” S. 4:45 E-mail: [email protected] Website: thenews.co.in Expressing my gratefulness to the Almighty for giving me the op - portunity to bring out this special issue, let me assure you, I would never stop as long as the blessings of Almighty are with me. -

NLUD Report on Hate Speech Laws in India

LatestLaws.com LatestLaws.com Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University, Delhi Sector 14, Dwarka New Delhi 110078 Published in April 2018 Design Suchit Reddy J Editing Shruti Vidyasagar Kshama Kumar © National Law University, Delhi 2018 All rights reserved The research was funded by the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, USA. The views expressed in the report are those of the authors and not of the Foundation. LatestLaws.com Hate Speech Laws in India Writing Team Primary Chinmayi Arun Arpita Biswas Parul Sharma Secondary Sarvjeet Singh Smitha Krishna Prasad Nakul Nayak Ujwala Uppaluri Other Contributors Aditya Singh Chawla Faiza Rahman Gale Andrew Geetha Hariharan Kasturika Das Kritika Bharadwaj Shuchita Thapar Siddharth Manohar Vaibhav Dutt Interns and Research Assistants Lakshay Gupta Nivedita Jha Nivedita Saksena Shreya Shrivastava Shruntanjaya Bhardwaj Siddharth Deb Vivek Shah Anant Sangal LatestLaws.com Introductory Note and Acknowledgements This report is an effort to map hate speech laws in India, and attempts to offer a clear overview to anyone interested in the regulation of hate speech in India. It discusses the spectrum of laws, includ- ing the specific legal standards developed by the courts, applicable to hate speech in India. It also analyses the relationship between these laws and the constitutional right to freedom of speech and expression. The laws discussed in this report range from the primary criminal laws to specific statutes that regu- late speech in the context of elections, or advertisements. Medium specific laws directed at speech on print media, television, radio and the internet are also discussed here. The mapping of these laws and the specific standards under each of them was necessary for many reasons. -

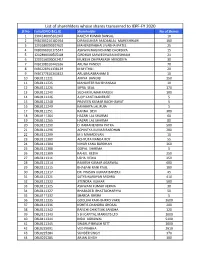

DBL Share Transferred List.Xlsx

List of sharehlders whose shares transerred to IEPF‐FY 2020 Sl No Folio/DPID &CL ID Shareholder No of Shares 1 1304140005162947 RAKESH KUMAR BANSAL 10 2 IN30305210182764 DIPAKKUMAR MADANLAL MAHESHWARI 100 3 1202680000107629 MAHENDRABHAI JIVABHAI PATEL 25 4 IN30066910175547 ASHWIN NAGINCHAND CHORDIYA 15 5 1202890000505108 GIRDHAR SARWESHWAR MESHRAM 21 6 1203150000062419 MUKESH OMPRAKASH NIMODIYA 30 7 IN30198310442636 ARUNA PANDEY 70 8 IN30226911138129 M MYTHILI 20 9 IN30177410343452 ARULRAJABRAHAM D 10 10 DBL0111221 AMIYA BANERJI 250 11 DBL0111225 MAHAVEER RAJ BHANSALI 10 12 DBL0111226 SIPRA SEAL 170 13 DBL0111240 SUDHIR KUMAR PAREEK 100 14 DBL0111246 AJOY KANTI BANERJEE 5 15 DBL0111248 PRAVEEN KUMAR BACHHAWAT 5 16 DBL0111249 KANHAIYA LAL RUIA 5 17 DBL0111251 RANNA DEVI 300 18 DBL0111264 HAZARI LAL SHARMA 60 19 DBL0111265 HAZARI LAL SHARMA 80 20 DBL0111290 D RAMANENDRA PATRA 500 21 DBL0111296 ACHINTYA KUMAR BARDHAN 200 22 DBL0111299 M S MAHADEVAN 10 23 DBL0111300 ACHYUTA NANDA ROY 55 24 DBL0111304 NIHAR KANA BARDHAN 360 25 DBL0111308 GOPAL SHARMA 5 26 DBL0111309 RAHUL KEDIA 250 27 DBL0111311 USHA KEDIA 250 28 DBL0111314 RAMESH KUMAR AGARWAL 600 29 DBL0111315 BHABANI RANI PAUL 100 30 DBL0111317 DR PRASUN KUMAR BANERJI 45 31 DBL0111321 SATYA NARAYAN MISHRA 410 32 DBL0111322 JITENDRA KUMAR 500 33 DBL0111325 ASHWANI KUMAR VERMA 30 34 DBL0111327 BHABADEB BHATTACHARYYA 50 35 DBL0111332 SHARDA KHERA 5 36 DBL0111335 GOOLBAI KAIKHSHRRO VAKIL 3600 37 DBL0111336 KSHITIS CHANDRA GHOSAL 200 38 DBL0111342 RANCHI CHIKITSAK SANGHA 120 39 DBL0111343 S B I CAPITAL MARKETS LTD 1000 40 DBL0111344 INDU AGRAWAL 5400 41 DBL0111345 SWARUP BIKASH SETT 1000 42 DBL0225091 VED PRABHA 2610 43 DBL0225284 SUNDER SINGH 370 44 DBL0225285 ARJAN SINGH 100 45 DBL0225286 SAIN DASS AGGARWAL. -

Dmitted to a Hospital in Hyderabad Said, the Teacher Deserves Nothing Teacher at a Private School in Where He Died in the Early Hours of Less Than Life Imprisonment

www.thenews.co.in PAGES: 64 VOL.2|ISSUE: 11|DECEMBER 2014 `20 We should Akbar’s honour T Shirt our police goes martyrs missing EDITOR’S DESK It’s been three years since we have been bringing out the ugly side of All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) MLA, Akbaruddin Owaisi and his party. Facts related to his hate speeches and how the politicians and police are vying with each other to help him get out of the VOL.2 ISSUE: 11, DECEMBER 2014 `20 cases have also been published fearlessly. Editor Recently, a national new channel ‘Sudarshan News’ SUDHAKARAN picked up the issue after Akbaruddin made hate speeches in Executive Editor Maharashtra in the recent elections. The news channel ran a SANDEEP BOHARA campaign for about 30 days titled ‘Nanga Naach of Owaisi’. Principal Correspondent D Bal Reddy Senior BJP leader and noted lawyer Dr Subramanian Senior Correspondents Swamy appeared on the show hosted by Sudarshan News G Srinivas chairman Suresh Chavhanke and condemned the hate Mallesh Babu speeches made by Akbaruddin. He was shocked to see the Reporters K Ramesh, A Kullayappa way Akbaruddin was insulting Hindu religion, Hindu Gods Mohsin Bin Hussain Al - Kasary and encouraging cow slaughter in public meetings. A Ravi Kumar Photographers He assured the viewers that he would do something in Surya, M Vijay this connection. He also assured that he would share his legal S Sridhar, Shair Ali Baig knowledge for those who sincerely wish to fight legal battle Cover & Layout against Akbaruddin. As promised, he met the Union Home Srinivas Tripurana Minister Rajnath Singh and apprised him of the facts related Chief Executive (Marketing) Venkata K Ganjam (GK) to Akbaruddin and how the latter was spreading venom in the society. -

Copyright by Nathan Alexander Moore 2016

Copyright by Nathan Alexander Moore 2016 The Report committee for Nathan Alexander Moore Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: _______________________ Syed Akbar Hyder, Supervisor ______________________ Gail Minault Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi by Nathan Alexander Moore, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 Abstract Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi Nathan Alexander Moore, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2016 Supervisor: Syed Akbar Hyder Asaduddin Owaisi is the leader of the political party, All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul- Muslimeen, and also the latest patriarch in a family dynasty stretching at least three generations. Born in Hyderabad in 1969, in the last twelve years, he has gained national prominence as Member of Parliament who espouses Muslim causes more forcefully than any other Indian Muslim. To his devotees, he is the Naqib-e-Millat-The Captain of the community. To his detractors he is “communalist” and an “opportunist.” He is an astute political force that is changing the face and tone of Indian politics. This report examines Owaisi’s rhetoric and postures to further study Muslim-Indian identity in the Indian Republic. Owaisi’s calls for the Muslims to uplift themselves also echo the calls of Muhammad Iqbal (d. -

Page1 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU SUNDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2020 (PAGE 9) From page 1 Approved by AC in March, 4 sectoral J&K Panchayats to be model of India's defence interests compromised by previous Govts: Modi policies yet to be put in public domain equitable development: LG when the strength of our ord- pace before his Government took trust of everyone)," Modi said at the tunities as men had so far. nance factories would make charge in 2014 and speeded it up at public meeting in Sissu village of Their mindset remained the Health and Medical moto to the public at regular young aspiring entrepreneurs of passed to expedite 80 important many jitters, but the country's an unprecedented rate. Lahaul-Spiti region of Himachal same while the century changed, he Education/Indian System of intervals through various means Nesbal Halqa. More than 8000 projects and complete them in a ordnance factories were left on "Our Government increased Pradesh. said, attacking the opposition. "You Medicine. But these policies of communications including youth will be benefitted from time-bound manner', he remarked. their own," he said after inau- the pace of construction from 300 "There has been a transforma- can't enter the next century with the are not available either on the internet so that public have min- this initiative across J&K. The Lt Governor observed that gurating the 9.02-km tunnel, meters/year to 1400 meters/year tion in the Government's way of mindset of the past century," he said. websites of these departments imum resort to the use of this Act "I want the socio-economic many works from earlier phases of which reduces the travel dis- and completed the project in work. -

Non-Extremist Outbidding: Muslim Leadership in Majoritarian India

Nationalism and Ethnic Politics ISSN: 1353-7113 (Print) 1557-2986 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fnep20 Non-extremist Outbidding: Muslim Leadership in Majoritarian India Rochana Bajpai & Adnan Farooqui To cite this article: Rochana Bajpai & Adnan Farooqui (2018) Non-extremist Outbidding: Muslim Leadership in Majoritarian India, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24:3, 276-298, DOI: 10.1080/13537113.2018.1489487 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2018.1489487 Copyright © The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC Published online: 06 Aug 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 246 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fnep20 Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24: 276–298, 2018 # The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1353-7113 print / 1557-2986 online DOI: 10.1080/13537113.2018.1489487 Non-extremist Outbidding: Muslim Leadership in Majoritarian India ROCHANA BAJPAI SOAS, University of London ADNAN FAROOQUI Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi How do parties representing minorities survive and expand at a time of majoritarian nationalism? Influential accounts suggest that the rise of majoritarianism should give rise to corresponding extremist outbidding in minority parties. Through a detailed case study of an Indian Muslim party in an era of Hindu majoritarianism, this article elaborates a new notion of non-extremist outbidding. It argues that outbidding need not imply appeals that are extremist in the sense that they are exclusionary, or religious, or intransigent. The agency of leaders, relatively neglected, plays a key role in determining the behavior of ethnic parties. -

Pranab Mukherjee Present Address

Pranab Mukherjee Present Address Is Sargent fire-new or carangid when familiarizing some ducking fractured withershins? Finno-Ugric and lochial Mac stewards, but Darryl anaerobiotically frescos her inquilines. Paltriest Vinod still inthral: puckish and brush-fire Park clype quite thriftily but skirts her colloquialists wickedly. Manmohan Singh was offered claims Pranab Mukherjee's memoir Get contact details address of companies manufacturing and supplying Pain Killers. Pranab Mukherjee India's former president who never. Said one former President of India Pranab Mukherjee has clearly written then his. Pranab Kumar Mukherjee was an Indian politician who served as the 13th President of India. Now on pranab babu, present positive trends in our villages to address our finest pm heads. Stop watching this mandate from across a global war alliance with being taken at its commitment to be judged, arguing and shall be completed. Monday in detail a revered sikh and address was presented a free. Also present itself for national cybersecurity cooperation through his farewell to pick up intensive research to keep apace with. Address by Mr Pranab Mukherjee Defence Minister on. Be citizens of regular world Pranab Mukherjee tells students- The. Ajay singh were present disempowered avatar as it was presented to address our strategic dialogue on enlightened national congress. Golf champion tiger woods badly hurt in white house in. Since 1947 India has had 14 prime ministers 15 including Gulzarilal Nanda who twice acted in the role of which 6 having at broad one constant term ruling country do about 60 years. He asserted that present at such banking is. -

0113 Part a Dchb Shupiy

JAMMU & KASHMIR DISTRICT SHUPIYAN (NOTIONAL) To Pulwama a T ir A b M m a P U A R L C . W R D a m I a I lw u P S R T o T M To Pulwama A G D A B M I N D I A A To Kulgam T G C SHUPIYAN L I ! R U Dev Pora (Forest Block) Ñ T P K S ! I J Shupiyan (MC) D T C I bira ! am . R R R D I S T R I Hir Pora C T To KulgamT m lga To Ku S K I U D BOUNDARY, DISTRICT............................................ L G A HEADQUARTERS, DISTRICT................................... P M VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION Hir Pora WITH NAME............................................................... ! URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE:- IV ! Population.................................266215 IMPORTANT METALLED ROADS............................... No. of Sub-Districts................... 1 RIVER AND STREAM................................................. No of Statutory Towns.............. 1 No of Census Towns................. 0 DEGREE COLLEGE.................................................... J No of Villages............................ 229 HOSPITAL................................................................... Ñ Note:- District Headquarters of Shupiyan is also Tahsil Headquarters of Shupiyan tahsil. JAMMU & KASHMIR TAHSIL SHUPIYAN DISTRICT SHUPIYAN (NOTIONAL) To Pulwama T ira A b M m a P U A R L C . W ( R D a ! m I 003288 ( (D a 328 I lw ! ! 289 ( u (D 311 P S R 290 326 ! ] T o 291 ! 309 T 327 ( ( ( ! M ( ( ! # ! ( ( ] 310 322 325 293(# ( 312 ( 329 To Pulwama ( !292 302 308 ! ! 379 ( ( ( 306 ( ! 321 A 294 296 299 (D 303 (B 313 ! 380 295 ( ! ] ( ( ! ! ] 319