The Geography of Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Development Programme

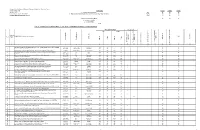

ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 16 - PROGRAMME 2015 PROGRAMME DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT JUNE, 2015 www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk FINAL ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2015-16 GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT http://www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Table of Contents S.No. Sector/Sub Sector Page No. 1 Abstract-I i 2 Abstract-II ii 3 Abstract-III iii 4 Abstract-IV iv-vi 5 Abstract-V vii 6 Abstract-VI viii 7 Abstract-VII ix 8 Abstract-VIII x-xii 9 Agriculture 1-21 10 Auqaf, Hajj 22-25 11 Board of Revenue 26-27 12 Building 28-34 13 Districts ADP 35-35 14 DWSS 36-50 15 E&SE 51-60 16 Energy & Power 61-67 17 Environment 68-69 18 Excise, Taxation & NC 70-71 19 Finance 72-74 20 Food 75-76 21 Forestry 77-86 22 Health 87-106 23 Higher Education 107-118 24 Home 119-128 25 Housing 129-130 26 Industries 131-141 27 Information 142-143 28 Labour 144-145 29 Law & Justice 146-151 30 Local Government 152-159 31 Mines & Minerals 160-162 32 Multi Sectoral Dev. 163-171 33 Population Welfare 172-173 34 Relief and Rehab. 174-177 35 Roads 178-232 36 Social Welfare 233-238 37 Special Initiatives 239-240 38 Sports, Tourism 241-252 39 ST&IT 253-258 40 Transport 259-260 41 Water 261-289 Abstract-I Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Programme-wise summary (Million Rs.) S.# Programme # of Projects Cost Allocation %age 1 ADP 1553 589965 142000 81.2 Counterpart* 54 19097 1953 1.4 Ongoing 873 398162 74361 52.4 New 623 142431 35412 24.9 Devolved ADP 3 30274 30274 21.3 2 Foreign Aid* * 148170 32884 18.8 Grand total 1553 738135 174884 100.0 Sector-wise Throwforward (Million Rs.) S.# Sector Local Cost Exp. -

R Functional 2 345003 BHU BRAH Dargai I

DISTRICT MALAKAND BASIC HEALTH UNITS S.No ID No Inst Name Tehsil/ Class Beds Locality Status 1 345002 BHU ASHAKI Dargai I - R Functional 2 345003 BHU BRAH Dargai I - R Functional 3 345004 BHU HERYANKOT Dargai I - R Functional 4 345005 BHU KHARKAI DHERI Dargai I - R Functional 5 345009 BHU GUNYAR THANA Batkhela I - R Functional 6 345010 BHU KHAR Batkhela I - R Functional 7 345011 BHU MEIKH BAND Batkhela I - R Functional 8 345013 BHU TOTAI Dargai I - R Functional 9 345014 BHU Gari Usman Khel Sum ranizai 1 - R Functional 10 345015 BHU MURA BANDA Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 11 345016 BHU NARI OBU Sum ranizai I - R Functional 12 345017 BHU PIRKHEL Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 13 345018 BHU SHINGRAI Sum ranizai I - R Functional 14 345019 BHU TAND GHOUND AGRA Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 15 345020 BHU WARTAIR Sum ranizai I - R Functional 16 345021 BHU BOOTANO KHAPA THANA Sum ranizai I - R Functional 17 345041 BHU KHARKAI DARGAI Sum ranizai I - R Functional 18 345042 BHU INZARGAI AGRA Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 19 345043 BHU MISHTA AGRA Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 20 345045 BHU WAZIR ABAD DARGAI Sum ranizai I - R Functional DISPENSARIES 1 345022 Civil Dispy: Sadullah khan kalay Sum ranizai I - R Functional 2 345024 Civil Dispy: Null thana Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 3 345025 Civil Dispy Bazdara bala palai Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 4 345026 Civil Dispy Badraga Sum ranizai I - R Functional 5 345027 Civil Dispy: Hero shah Sum ranizai I - R Functional 6 345028 Civil Dispy Manzari Baba Kot Swat Ranizai I - R Functional 7 345029 Civil -

DFG Part-L Development Settled

DEMANDS FOR GRANTS DEVELOPMENTAL EXPENDITURE FOR 2020–21 VOL-III (PART-L) GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA FINANCE DEPARTMENT REFERENCE TO PAGES DFG PART- L GRANT # GRANT NAME PAGE # - SUMMARY 01 – 23 50 DEVELOPMENT 24 – 177 51 RURAL AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT 178 – 228 52 PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING 229 – 246 53 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 247 – 291 54 HEALTH SERVICES 292 – 337 55 CONSTRUCTION OF IRRIGATION 338 – 385 CONSTRUCTION OF ROADS, 56 386 – 456 HIGHWAYS AND BRIDGES 57 SPECIAL PROGRAMME 457 – 475 58 DISTRICT PROGRAMME 476 59 FOREIGN AIDED PROJECTS 477 – 519 ( i ) GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (SETTLED) BUDGET REVISED BUDGET DEMAND MAJOR HEADS ESTIMATES ESTIMATES ESTIMATES NO. -

ADP 2021-22 Planning and Development Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Page 1 of 446 NEW PROGRAMME

ONGOING PROGRAMME SECTOR : Agriculture SUB-SECTOR : Agriculture Extension 1.KP (Rs. In Million) Allocation for 2021-22 Code, Name of the Scheme, Cost TF ADP (Status) with forum and Exp. upto Beyond S.#. Local June 21 2021-22 date of last approval Local Foreign Foreign Cap. Rev. Total 1 170071 - Improvement of Govt Seed 288.052 0.000 230.220 23.615 34.217 57.832 0.000 0.000 Production Units in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. (A) /PDWP /30-11-2017 2 180406 - Strengthening & Improvement of 60.000 0.000 41.457 8.306 10.237 18.543 0.000 0.000 Existing Govt Fruit Nursery Farms (A) /DDWP /01-01-2019 3 180407 - Provision of Offices for newly 172.866 0.000 80.000 25.000 5.296 30.296 0.000 62.570 created Directorates and repair of ATI building damaged through terrorist attack. (A) /PDWP /28-05-2021 4 190097 - Wheat Productivity Enhancement 929.299 0.000 378.000 0.000 108.000 108.000 0.000 443.299 Project in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). (A) /ECNEC /29-08-2019 5 190099 - Productivity Enhancement of 173.270 0.000 98.000 0.000 36.000 36.000 0.000 39.270 Rice in the Potential Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). (A) /ECNEC /29-08-2019 6 190100 - National Oil Seed Crops 305.228 0.000 113.000 0.000 52.075 52.075 0.000 140.153 Enhancement Programme in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). -

Pavement of Goat Walla Irrigationchannel, Thana Bandajat." 333,780

District. Project Description BE 2016-17 MALAKAND MD15D00286-"Pavement of Goat Walla IrrigationChannel, Thana Bandajat." 333,780 MALAKAND MD15D00287-Clearance of silts at Thana Bandajat. 333,780 MALAKAND MD15D00288-"Construction of GI wire, D/wall C/OAriq ur Rehman, Shawi Bund, U/C 278,150 Dheri Julagram." MALAKAND MD15D00291-Pavement of Street at Sultan Khat SaidraJeward U/C GU Khel 222,520 MALAKAND MD15D00292-"Protection wall to agriculture lands atV/C Anar Tangey, U/C GU 222,520 Khel." MALAKAND MD15D00293-Construction of R/Wall VC Palonow U/CHero Shah 111,260 MALAKAND MD15D00294-"Construction of Water channels atTotai, U/C Selai Patay." 166,890 MALAKAND MD15D00295-Construction of R/Wall at Quresh KalayU/C Badraga 139,070 MALAKAND MD15D00296-Construction of R/Wall at Abbas KallayU/C Badraga 166,890 MALAKAND MD15D00297-Construction of Irrigation Channel atQadar Kallai Union Council 111,260 Badraga MALAKAND MD15D00298-Construction of Irrigation Channel atGulo Shah Union Council Koper 278,150 MALAKAND MD15D00299-Construction of R/Wall at U/C SakhakotKhass. 144,630 MALAKAND MD15D00300-"Construction of D/Wall, Slab at JabanBala, near Power House, U/C 166,890 Dargai." MALAKAND MD15D00301-Construction of D/Wall at Saman Abad U/CLower Batkhela District 400,000 Malakand. MALAKAND MD15D00302-"Construction of D/Wall in U/C UpperBatkhela, PK-99, Malakand" 273,000 MALAKAND MD15D00303-Construction of PCC Irrigation ChannelN/H/O Ehsan Ullah U/C Dheri 222,520 Julagram. MALAKAND MD15D00304-Construction of PCC Irrigation channelChena-I U/C Dheri Julagram -

(MALE) MALAKAND at BATKHELA STATEMENT SHOWING the SCHOOL WISE DETAIL of FOLLOWING VACANT POSTS AS STOOD on 27-10-2020 Union S.No

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT EDUCATION OFFICER (MALE) MALAKAND AT BATKHELA STATEMENT SHOWING THE SCHOOL WISE DETAIL OF FOLLOWING VACANT POSTS AS STOOD ON 27-10-2020 Union S.No. EMIS Name of School Level PST B-12 Total Council/Ward 1 19524 GPS No.1 Bararo sar Primary Agra 3 3 2 19523 GPS No.2 Bararo Sar Primary Agra 1 1 3 19528 GPS Bazargai Agra Primary Agra 2 2 4 19554 GPS Ghund Agra Primary Agra 2 2 5 19607 GPS Meshta Primary Agra 2 2 6 19617 GPS Nazir Abad Primary Agra 2 2 7 38952 GPS Parokhel Primary Agra 1 1 8 19562 GPS Hadi khas Primary Alladand 3 3 9 19550 GPS Fazal Abad Primary Alladand 1 1 10 19575 GPS Jalawanan Primary Alladand 1 1 11 19511 GPS Amandara Primary Alladand 1 1 12 19805 GPS Bajawaro kallay Primary Badragga 2 2 13 28720 GPS Gul Ghafoor Banda Primary Badragga 2 2 14 19828 GPS Hassan Abad Primary Badragga 1 1 15 29675 GPS Muqam Kallay Primary Badragga 2 2 16 19875 GPS Qadar Kallay Primary Badragga 2 2 17 19909 GPS Zahoor Abad Primary Badragga 2 2 18 19803 GPS Badragga Primary Badragga 2 2 19 19496 GPS Akbar Abad Primary Batkhela (Lower) 4 4 20 19495 GPS Akhtar Ghoundai Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Lower) 2 2 21 19502 GPS Gulshan Abad Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Lower) 1 1 22 19499 GPS No.3 Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Lower) 3 3 23 19506 GPS Sangina Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Lower) 1 1 24 19507 GPS Upper Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Middle) 1 1 25 29663 GPS Khatkai Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Upper) 1 1 26 19501 GPS Gharib Abad Primary Batkhela (Upper) 1 1 27 19503 GPS Gumbat Batkhela Primary Batkhela (Upper) 1 1 Union S.No. -

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils Alongwith Seats Detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils alongwith seats detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa No. of General Seats in No. of Seats in VC/NC (Categories) Names of S. Names of Tehsil Councils No falling in each Neighbourhood Village N/Hood Total Col Peasants/Work S. No. Village Councils (VC) S. No. Women Youth Minority . district Council Councils (NC) Councils Councils 7+8 ers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Abbottabad District Council 1 1 Dalola-I 1 Malik Pura Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 2 Dalola-II 2 Malik Pura Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 3 Dabban-I 3 Malik Pura Urban-III 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 4 Dabban-II 4 Central Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 5 Boi-I 5 Central Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 6 Boi-II 6 Central Urban-III 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 7 Sambli Dheri 7 Khola Kehal 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 8 Bandi Pahar 8 Upper Kehal 5 7 12 4 2 2 2 9 Upper Kukmang 9 Kehal 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 10 Central Kukmang 10 Nawa Sher Urban 5 10 15 4 2 2 2 11 Kukmang 11 Nawansher Dhodial 6 10 16 4 2 2 2 12 Pattan Khurd 5 5 2 1 1 1 13 Nambal-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 14 Nambal-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 Abbottabad 15 Majuhan-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 16 Majuhan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 17 Pattan Kalan-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 18 Pattan Kalan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 19 Pattan Kalan-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 20 Sialkot 6 6 2 1 1 1 21 Bandi Chamiali 6 6 2 1 1 1 22 Bakot-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 23 Bakot-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 24 Bakot-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 25 Moolia-I 6 6 2 1 1 1 26 Moolia-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 1 Abbottabad No. -

Development Budget Estimates 2017-18

District Project Description BE 2017-18 MALAKAND MD15D00311-Construction of D/Wall C/O Said Muhammadin U/C 75,670 Khar District Malakand MALAKAND MD15D00354-Construction of Kacha road from LoyaBanda to 400,000 Jismas. MALAKAND MD15D00405-Installation of Hand Pumps in U/C ThanaBandajat in 270,944 PK-99 District Malakand. MALAKAND MD15D00410-Installation of Solar System in verious Masjids of 900,000 U/C Totakan Phase-1,Distrit Malakand MALAKAND MD15D00456-General Building works at GGHS Malakand 262,456 MALAKAND MD15D00458-"Construction of 2 Nos. Bathrooms at GHSPalai, U/C 400,000 Palai." MALAKAND MD15D00463-Pavement of Street & Construction of R/Wall near 1,600,000 GMS Pirkhushal Baba, Serai, U/C Upper Batkhela MALAKAND MD15D00464-Construction of Bath Rooms in GHS No.2Dherai 600,000 Alladhand in U/C Dherai MALAKAND MD15D00470-Construction of Bath Rooms and Gate inGGHS 266,238 Thana MALAKAND MD15D00482-"Construction of G.I shed at GHS NO.1 Thana." 500,000 MALAKAND MD15D00496-Construction of 2 Nos. Rooms at BHUKhar. 865,047 MALAKAND MD15D00499-"Reconstruction of Service Block atCivil Dispensary, 1,258,581 Bazdara U/C Palai." MALAKAND MD15D00523-"Construction of Drain PCC StreetPavement N/H/O 449,286 Qayum Khan Miras khel, Israr Bacha Lahore Khel, HamidLahore Khel, Shah Jehan Koto, Daud khan & Ibrar shaba Khel,Aziz MALAKAND MD15D00526-"PCC Street/Street VCs Khan Pala, SaidAbad, Baro in 153,210 U/C Dherai PK-99 District Malakand." MALAKAND MD15D00532-PCC Drain Karim Baba Line Malakand U/CMalakand 50,000 District Malakand. MALAKAND MD15D00543-PCC Roads/Streets U/C Thana BandajatDistrict 147,664 Malakand. -

AR Tmas Malakand for 2016-17.Pdf

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS IN DISTRICT MALAKAND KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATION AND ACRONYMS………………………………………………………….i PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………………………E rror! Bookmark not defined. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………iii I: Audit Work Statistics…………………………………………………………………….vi II: Audit Observations regarding Financial Management………………………………….vi III: Outcome Statistics……………………………………………………………………vii IV: Irregularities pointed out ……………………………………………………………viii V: Cost Benefit……………………………………………………………………………viii CHAPTER-1………………………………………………………………………………………1 1.1 Tehsil Municipal Administrations, in District Malakand……………………………..1 1.1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ……………………….1 1.2 TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION BATKHELA…………………………4 1.2.1 Irregularity & Non-compliance………………………………………………….5 1.2.2 Internal Control Weaknesses …………………………………………………….11 1.3 TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION DARGAI……………………………..13 1.3.1 Irregularity & Non-compliance…………………………………………………..14 ANNEXURE……………………………………………………………………………………..22 Annexure-1 Detail of MFDAC……………………………………………………………………21 Annexure-2 Detail of Petrol/CNG Pumps under the juridiction of TMA Batkhela……………...23 Annexure-3 Detail of outstanding water charges…………………………………………………24 Annexure-4 Detail of non-imposition of penalty on a/c of late deposit of instatllment…………..25 Annexure-5 Detail showing non-adjustment of income tax………………………………………26 -

Ethnomedicinal Survey of Plants of Valley Alladand Dehri, Tehsil

International Journal of Basic Medical Sciences and Pharmacy (IJBMSP) 23 Vol. 3, No. 1, June 2013, ISSN: 2049-4963 © IJBMSP www.ijbmsp.org Ethnomedicinal Survey of plants of Valley Alladand Dehri, Tehsil Batkhela, District Malakand, Pakistan Alamgeer1,Taseer Ahmad1, Muhammad Rashid4, Muhammad Nasir Hayat Malik1, Muhammad Naveed Mushtaq1, Jahangir khan1, 3 , Raheela Qayyum2, Abdul Qayum Khan1, Nasir Muhammad5 1Faculty of Pharmacy university of Sargodha, Sargodha, Pakistan 2Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad, Pakistan 3Departement of pharmacy, university of malakand, KPK, Pakistan. 4School of pharmacy the university of Faisalabad, Pakistan. 5Department of Chemistry, Kohat University of Science and Technology, KPK, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Abstract – The aim of this survey was to evaluate and document ethnomedicinal knowledge of the Valley Alladand Dehri, Tehsil Batkhela, District Malakand, which has high medicinal plants prospective. Ethnomedicinal informations including local names, local medicinal uses of plants, were collected through an open-ended questionnaire. These Informations were only reported when at least 10 interviewees verified it. The study showed that the local people used approximately 92 species of different plants for various diseases like in high blood pressure as diuretic (18%), diarrhea (11%) and diabetes (8%). The leading families out of 53 in medicinal indications were Lamiaceae (12%), Asteraceae (8%), Cucurbitaceae (8%) and Solanaceae (8%). It was also observed that local collectors are unaware of proper collection, and preservation techniques, due to which its active ingredients are lost. It is concluded from our survey that this ethnomedicinal study will definitely provide a folkloric claim base for researchers and also asses in the treatment of local diseases. -

Dispenser Course

Intermediate with Science & Diploma in Pharmacy Technician / Dispenser Course. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Scoring Key: 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 18-32 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks S.S.C 30 22 18 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) F.A/FSc 30 22 18 Dispenser pharmacy technician (BPS-12) Total;- 60 44 36 3. Professional Training Marks 20 15 12 4. Experience Certificate 5. Interviews Marks Total;- LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF DISPENSER PHARMACY TECHNICIAN BPS-12 BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # Appli: Remarks Domicile Malrks= 7 Total Marks Total Marks Marks Marks B.A Dateof Birth Qualification Marks M.A Division Division Marks Experience of Professional/Training Professional/Training One Stage Above 7 Above One Stage Interview MarksInterview Marks 8 Two Stage Above 10 10 Above Two Stage Year of Experience of Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Muhammad Israr S/o Gul Muhammad, Room no.1 nursing hospital rehan medical institute 1 10/4/1991 Intermediate Malakand 3rd 18 18 36 36 hayatabad phase V peshawar. 3rd 2 kameen khan s/o madat khan, post office magan bhagan district kurm agency 1/4/2014 Intermediate Kurran agency 1st 30 2nd 22 52 52 Muhammad sadiq s/o Muhammad Humayon, house no. H308, street no.D3 phase 1 3 21-04-1992 B.A kark 2nd 22 2nd 22 44 44 hayatabad. -

Second Science Education Sector Project

Completion Report Project Number: 26326 Loan Number: 1534-PAK[SF] November 2007 PAKISTAN: Second Science Education Sector Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (PRe/PRs) At Appraisal At Project Completion (31 July 1997) (30 June 2007) PRe1.00 = $0.025 $0.017 $1.00 = PRs40.56 PRs60.00 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BME – benefit monitoring and evaluation EA – executing agency ECNEC – Executive Committee of the National Economic Council FATA – Federally Administered Tribal Areas FCU – federal coordinating unit IPSET – Institute for the Promotion of Science Education and Training M&E – monitoring and evaluation MOE – Ministry of Education MPL – multipurpose laboratory MRR – mathematics resource room NEEC – National Education Equipment Center NISTE – National Institute for Science and Technical Education NSAC – National Scientific Advisory Committee NSC – National Steering Committee NWFP – North-West Frontier Province OECF – Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund PCC – provincial coordination committee PC-I – Planning Commission Proforma I PED – provincial education department PIU – project implementation unit RRP – report and recommendation of the President SAP – Social Action Programme SEC – science education center SHS – science high school NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2007 ends on 30 June 2007. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. (iii) “Government” refers to the Government of Pakistan. Vice President L. Jin, Operations 1 Director General J. Miranda, Central and West Asia Regional Department Director P. Fedon, Pakistan Resident Mission Team leader S. Abbas, Senior Project Implementation Officer, Pakistan Resident Mission Team member N.