Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 109, 1989-1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

Felix Mendelssohn's Career As a Composer

10-27 Sat Mat.qxp_Layout 1 10/18/18 2:07 PM Page 29 Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair String Quintet in B-flat major, Op. 87 Felix Mendelssohn elix Mendelssohn’s career as a composer was not strictly that of the mainstream. As a Fand conductor was flourishing in 1845. result, certain of his works — such as the first He was considering competing job offers and last movements of this quintet — can from two crowned heads (the Kings of Prus - sometimes sound less like classic chamber sia and of Saxony), he was deriving satisfac - music than like little string symphonies, re - tion from his pet project of elevating the flecting a hierarchy in which the first violin Leipzig Conservatory into a world-class in - spends more time in the spotlight than the stitution, and he enjoyed great happiness on lower-lying “accompanying” instruments. In the home front, the more so when he and his fact, his interest in those first and last move - wife greeted the arrival of their fifth child, ments seems fixed less on the themes them - Lili. There is no way that the composer, who selves than on the harmonic and structural was only 36 years old, could have known processes used in developing them. Wilhelm when he wrote the B-flat-major Quintet that Altman, writing in the classic Cobbett’s Cyclo - it would be among his last works. He died two pedic Survey of Chamber Music , perspica - years later after a series of strokes. -

Fundamental Techniques in Viola Spaces of Garth Knox. (2016) Directed by Dr

ÉRTZ, SIMON ISTVÁN, D.M.A. Beyond Extended Techniques: Fundamental Techniques in Viola Spaces of Garth Knox. (2016) Directed by Dr. Scott Rawls. 49 pp. Viola Spaces are often seen as interesting extra projects rather than valuable pedagogical tool that can be used to fill where other material falls short. These works can fill various gaps in the violist’s literature, both as pedagogical and performance works. Each of these works makes a valuable addition to the violist’s contemporary performance repertoire as a short, imaginative, and musically satisfying work and can be performed either individually or as part of a smaller set in a larger program (see Appendix A). They all also present interesting technical challenges that explore what are seen as extended techniques but can also be traced back to work on some of the fundamentals of viola technique. Etudes for viola are often limited to violin transcriptions mostly written in the eighteenth, nineteenth, or early twentieth centuries. Contemporary etudes written specifically for viola are valuable but are usually not as comprehensive or as suitable for performance etudes as are Viola Spaces. Few performance etudes cover the technical varieties that are presented in these works of Garth Knox. In this paper I will discuss the historical background of the viola and etudes written for viola. Many viola etudes written in the earlier history of the viola have not continued to be published; this study will also look at why some survived and others are no longer used. Compared to literature for the violin there are large gaps in the violists’ repertoire that Viola Spaces does much to fill; furthermore many violinists have asked for transcriptions of these works. -

103 CHAPTER V STRING SEXTET, OP. 47 in the Standard

CHAPTER V STRING SEXTET, OP. 47 In the standard instrumentation of two violins, two violas, and two cellos, only a half-dozen works for string sextet, all from the Romantic tradition, enjoy a place in the standard repertoire today. These are: the two sextets of Johannes Brahms, op. 18 in B f and op. 36 in G; Dvorak’s Sextet in A, op. 48; and the program works of the Romantic era, Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, Tchaikowsky’s Souvenir di Florence, and Richard Strauss’s Prelude to Capriccio. The efforts by Vincent d’Indy and Joseph Joachim Raff, as well as a handful of their lesser-known contemporaries, have fallen into obscurity. In the post-Romantic era, contributions to the genre have come from Frank Bridge, Erich Korngold, Bohuslav Martinu˚, Darius Milhaud, Walter Piston, Quincy Porter, and Max Reger, along with a few dozen works from lesser-known composers.1 Part of the reason for this sparsity of repertoire can be attributed to the overwhelming popularity of the string quartet, which since Haydn’s time has been the accepted proving ground for composers of chamber music. Another factor, in the post- 1 Margaret K. Farish, String Music in Print, 2nd ed. (New York, R.R. Bowker & Co, 1973), 289–90; 1984 Supplement (Philadelphia: Musicdata, Inc., 1984), 99–101; 1998 Supplement (Philadelphia: Musicdata, Inc.), 101–4. This periodically updated catalog offers the most complete listing of string chamber music available in the last thirty years. 103 104 tonal era, is the exploration of new and atypical sound combinations, which has led to a great proliferation of untraditional mixed ensembles, including acoustic and electronic instruments. -

Form, Style, and Influence in the Chamber Music of Antonin

FORM, STYLE, AND INFLUENCE IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF ANTONIN DVOŘÁK by MARK F. ROCKWOOD A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Mark F. Rockwood Title: Form, Style, and Influence in the Chamber Music of Antonin Dvořák This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Stephen Rodgers Chairperson Drew Nobile Core Member David Riley Core Member Forest Pyle Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Mark F. Rockwood This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial – Noderivs (United States) License. iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Mark F. Rockwood Doctor of Philosophy School of Music and Dance June 2017 Title: Form, Style, and Influence in the Chamber Music of Antonin Dvořák The last thirty years have seen a resurgence in the research of sonata form. One groundbreaking treatise in this renaissance is James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s 2006 monograph Elements of Sonata Theory : Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth- Century Sonata. Hepokoski and Darcy devise a set of norms in order to characterize typical happenings in a late 18 th -century sonata. Subsequently, many theorists have taken these norms (and their deformations) and extrapolate them to 19 th -century sonata forms. -

Americanensemble

6971.american ensemble 6/14/07 2:02 PM Page 12 AmericanEnsemble Peter Serkin and the Orion String Quartet, Tishman Auditorium, April 2007 Forever Trivia question: Where Julius Levine, Isidore Cohen, Walter Trampler and David Oppenheim performed did the 12-year-old with an array of then-youngsters, including Richard Goode, Richard Stoltzman, Young Peter Serkin make his Ruth Laredo, Lee Luvisi, Murray Perahia, Jaime Laredo and Paula Robison. New York debut? The long-term viability of the New School’s low-budget, high-star-power series (Hint: The Guarneri, is due to several factors: an endowment seeded by music-loving philanthropists Cleveland, Lenox and such as Alice and Jacob Kaplan; the willingness of the participants to accept modest Vermeer string quartets made their first fees; and, of course, the New School’s ongoing generosity in providing a venue, New York appearances in the same venue.) gratis. In addition, Salomon reports, “Sasha never accepted a dime” during his 36 No, not Carnegie Recital Hall. Not the years of labor as music director or as a performer (he played in most of the 92nd Street Y, and certainly not Alice Tully concerts until 1991, two years before his death). In fact, Sasha never stopped Hall (which isn’t old enough). New Yorkers giving—the bulk of his estate went to the Schneider Foundation, which continues first heard the above-named artists in to help support the New School’s chamber music series and Schneider’s other youth- Tishman Auditorium on West 12th Street, at oriented project, the New York String Orchestra Seminar. -

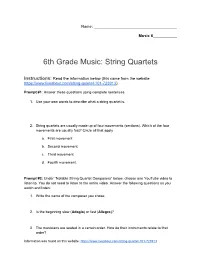

6Th Grade Music: String Quartets

Name: ______________________________________ Music 6___________ 6th Grade Music: String Quartets Instructions: Read the information below (this came from the website https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913). Prompt #1: Answer these questions using complete sentences. 1. Use your own words to describe what a string quartet is. 2. String quartets are usually made up of four movements (sections). Which of the four movements are usually fast? Circle all that apply a. First movement b. Second movement c. Third movement d. Fourth movement. Prompt #2: Under “Notable String Quartet Composers” below, choose one YouTube video to listen to. You do not need to listen to the entire video. Answer the following questions as you watch and listen: 1. Write the name of the composer you chose. 2. Is the beginning slow (Adagio) or fast (Allegro)? 3. The musicians are seated in a certain order. How do their instruments relate to that order? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 4. How do the musicians respond to each other while playing? Prompt #3: Under Modern String Quartet Music, find the Love Story quartet by Taylor Swift. Listen to it as you answer using complete sentences. 1. Which instrument is plucking at the beginning of the piece? (If you forgot, violins are the smallest instrument, violas are a little bigger, cellos are bigger and lean on the floor). 2. Reflect on how this version of Love Story is different from Taylor Swift’s original song. How would you describe the differences? What does this version communicate? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 String Quartet 101 All You Need to Know About the String Quartet The Jerusalem Quartet, a string quartet made of members (from left) Alexander Pavlovsky, Sergei Bresler, Kyril Zlontnikov and Ori Kam, perform Brahms’s String Quartet in A minor at the 92nd Street Y on Saturday night, October 25, 2014. -

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Enregistré par Little Tribeca à Paris du 19 au 23 juin 2015 Direction artistique et postproduction : Émilie Ruby Prise de son : Émilie Ruby assistée d’Ignace Hauville English translation by John Tyler Tuttle Deutsche Übersetzung von Gudrun Meier Photos © Caroline Doutre Design © 440.media AP154 Little Tribeca p 2015 © 2017 1, rue Paul Bert 93500 Pantin, France apartemusic.com PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) NOVUS QUARTET YOUNG-UK KIM 1ST VIOLIN, JAEYOUNG KIM 2ND VIOLIN SEUNGWON LEE VIOLA WOONG-WHEE MOON CELLO LISE BERTHAUD VIOLA OPHÉLIE GAILLARD CELLO String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Op. 11 Quatuor à cordes n° 1 en ré majeur, op. 11 1. Moderato e simplice 11’41 2. Andante cantabile 7’25 3. Scherzo. Allegro non tanto e con fuoco 4’04 4. Finale. Allegro giusto 6’55 String Sextet in D minor “Souvenir de Florence”, Op. 70 Sextuor à cordes en ré mineur « Souvenir de Florence », op. 70 5. Allegro con spirito 10’21 6. Adagio cantabile e con moto 10’28 7. Allegretto moderato 6’19 8. Allegro vivace 7’08 Du Quatuor au Sextuor, les jalons du succès Auteur de nombreux chefs-d’œuvre de la travaillé au ministère des Communications, musique romantique, parmi lesquels Le Lac Alexandre Borodine était chimiste, César Cui des cygnes, Casse-Noisette, Eugène Onéguine, ingénieur, Nikolaï Rimski-Korsakov officier le Concerto pour piano n° 1 en si bémol mineur, de marine. op. 23 ou encore le Concerto pour violon en ré majeur, op. 35, Piotr Ilitch Tchaïkovski est Tchaïkovski démissionna en 1863 pour se encore aujourd’hui l’un des compositeurs les consacrer entièrement à son art. -

Bernard Haitink 52 Camilla Tilling

Table of Contents | Week 24 7 bso news 15 on display in symphony hall 16 the boston symphony orchestra 19 old strains reawakened: the boston symphony’s historical instrument collection by douglas yeo 25 this week’s program Notes on the Program 26 The Program in Brief… 27 Franz Schubert 33 Gustav Mahler 47 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 51 Bernard Haitink 52 Camilla Tilling 54 sponsors and donors 64 future programs 66 symphony hall exit plan 67 symphony hall information program copyright ©2013 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo of BSO piccolo player Cynthia Meyers by Stu Rosner BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus, endowed in perpetuity seiji ozawa, music director laureate 132nd season, 2012–2013 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. Edmund Kelly, Chairman • Paul Buttenwieser, Vice-Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Stephen B. Kay, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O’Block, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chairman • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer William F. Achtmeyer • George D. Behrakis • Jan Brett • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles W. Jack, ex-officio • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Joyce G. Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Carmine A. Martignetti • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Susan W. Paine • Peter Palandjian, ex-officio • Carol Reich • Arthur I. -

Chamber Music Repertoire Trios

Rubén Rengel January 2020 Chamber Music Repertoire Trios Beethoven , Piano Trio No. 7 in B-lat Major “Archduke”, Op. 97 Beethoven , String Trio in G Major, Op. 9 No. 1 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 Brahms , Horn Trio E-lat Major, Op. 40 U. Choe, Piano Trio ‘Looper’ Haydn, P iano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 Haydn, Piano Trio in C Major, Hob. XV: 27 Mendelssohn , Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Mendelssohn, Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Mozart , Divertimento in E-lat Major, K. 563 Rachmaninoff, Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor Saint-Saëns , Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 18 Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 Stravinsky , L’Histoire du Soldat Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 Quartets Arensky , Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Cellos in A minor, Op. 35 No. 2 (Viola) Bartok, String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Sz. 40 Bartok , String Quartet No. 5, Sz. 102, BB 110 Beethoven , Piano Quartet in E-lat Major, Op. 16 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 5 in A Major, Op. 18 No. 5 Beethoven, String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2 Borodin , String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Debussy , String Quartet in G Major, Op. 10 (Viola) Dvorak, Piano Quartet No. 2 in E-lat Major, Op. -

“Music Hath Charms”

CHAMBER MUSIC ON THE HILL in residence at McDaniel College in its 26th Season Proudly Presents “Music Hath Charms” featuring Charm City Chamber Players Violists: Karin Brown and Renate Falkner Cellists: Daniel Levitov and Steven Thomas Guest Violinists: Brent Price and Christian Simmelink Sunday, September 20, 2015 3:00 p.m. The Forum, Decker College Center McDaniel College, Westminster, MD Funded in part by a Community Arts Development Grant from the Carroll County Arts Council and the Grants for Organizations Program from the Maryland State Arts Council. Program Notes Luigi Boccherini (1743 -1805) was roughly contemporary with Joseph Haydn and had a rather colorful life. Son of a professional double bass player, Luigi adopted the cello and was playing professionally by the age of thirteen. After four years in Rome, to complete his musical studies, he set off on a series of continental tours with a violinist colleague. In Paris, in 1768, he is said to have “created a sensation ” both for his playing and for his compositions – trios and quartets. He was persuaded to settle in Spain as a court musician, eventually for the Crown Prince, Don Luis. He married a Spanish girl and composed prolifically until his patron ’s death in 1785. His next employer was King Frederick William of Prussia but, when the latter died in 1797, he was left without income and returned to Spain. For a while he was supported by the French Ambassador, Lucien Bonaparte (the Emperor ’s brother), but when the latter was recalled in 1802, Boccherini was left to eke out a meager living rearranging his compositions to in- clude the guitar, then a fashionable instrument. -

Téléchargez La Version

sm13-X_Cover_NoUPC.qxd 6/26/08 10:42 AM Page 1 www.scena.org sm13-X_p02_c_new.qxd 6/26/08 11:34 AM Page 4 sm13-X_Ads2.qxd 6/25/08 11:08 PM Page 3 GK;BGK;I9ED9;HJI:;B7I7?IED(&&. FHE=H7CC;:;I7?IED MOZART, L’ORCHESTRE H^iZ>ciZgcZi/www.lanaudiere.org 8djgg^Za/ [email protected] BAROQUE DE FREIBURG Iae]dcZ/1 800 561-4343dj 450 759-7636 UNE GRANDE & CHRISTIAN GERHAHER : 8?BB;JJ;H?; UN MIRACLE 1 800 561-4343_djg PREMInRE 1 866 842-2112hd^g g MONTRmAL L;D:H;:?';H7EçJ%(&> 6be]^i]}igZYZ?da^ZiiZ DG8=:HIG:76GDFJ:9:;G:>7JG< OCTOBRE =ejj\h_[ZLED:;H=EBJP!Y^gZXi^dc AÉdgX]ZhigZeVgiV\ZaÉV[ÒX]ZVkZXaZWVgnidc8]g^hi^Vc <Zg]V]Zg!YdciaZh^ciZgegiVi^dchdciifjVa^ÒZh CONCURRENTS La Presse DEPAYS YZ»b^gVXaZ¼eVg # 9^h_ij_Wd=;H>7>;H!WVgnidc *OHN'REW Beh[dpe9EFFEB7!XaVg^cZiiZYZWVhhZi DIRECTEUR ARTISTIQUE J[kd_iL7D:;HPM7HJ!Xdg Egd\gVbbZ/Hnbe]dc^Z!XdcXZgidh ZiV^ghYÉdegVYZBdoVgi BILLETS:(.!(+!'.!'(!E:ADJH:&* I7C;:?'(@K?BB;J LE GRAND BAL DES OISEAUX :ÞI',>%6be]^i]}igZYZ?da^ZiiZ 9ZhVXi^k^ihZiVc^bVi^dchhjgaZh^iZ YZaÉ6be]^i]}igZ#9iV^ahYVchaVhZXi^dc wkcZbZcihVjmmm$bWdWkZ_[h[$eh] DES ENVOLÉES LYRIQUES D’ALINE KUTAN À L’OISEAU DE FEU DE STRAVINSKI (&>%6be]^i]}igZYZ?da^ZiiZ DG8=:HIG:9J;:HI>K6A @[Wd#CWh_[P;?JEKD?!Y^gZXi^dc 7b_d[AKJ7D!hdegVcd Ij[mWhj=EE:O;7H!e^Vcd HIG6K>CH@> AÉD^hZVjYZ[ZjÄHj^iZ kZgh^dcYZ&.&. B:HH>6:C D^hZVjmZmdi^fjZh!edjge^Vcd ZieZi^idgX]ZhigZ DJ:AA:II: ?d^ZYZh<g^kZh!de#(' XgVi^dcÄegd_ZXi^dch hjg\gVcYXgVc <DJCD9!=6C9:A 6^ghedjgXdadgVijgZ H6>CI"H6ÜCH fj^kdfjZciaZhd^hZVjm PARTENAIRESFONDATEURS BILLETS :),!))!(*!',!E:ADJH:&* PARTENAIRESPUBLICSFONDATEURS DIFFUSEUROFFICIEL PARTENAIREMmDIA sm13-X_Ads2.qxd 6/25/08 11:27 PM Page 4 sm13-X_Ads2.qxd 6/26/08 11:44 AM Page 5 Du 9 juillet au 31 août Promotion Les plus grandes interprétations des artistes chez Deutsche Grammophon, Decca, Philips pour et CBC records se retrouvent maintenant 3 2 dans la collection Éloquence.