Doctor of Philosophy in Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB -

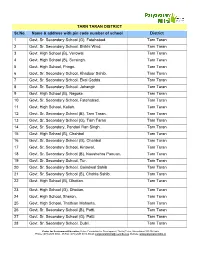

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

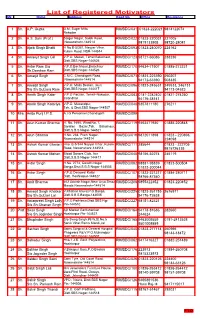

List of Registered Motivators SN Name Address Regd No Office Residence

List of Registered Motivators SN Name Address Regd No Office Residence 1 Sh. A.P. Gupta G.M, Suger Mills RM/BDC/031 01823-222021 9814122074 Nakodar 2 Sh. A.S. Sohi (Prof.) Satgur Nagar, Saloh Road, RM/BDC/022 01823-220031 221005 Nawanshahr-144514 9815133905 98720-28081 3 Sh. Ajaib Singh Bhatti H No.B-5/361, Nayyar Vihar, RM/BDC/093 01823-240070 224162 Kulam Road, NSR-144514 4 Sh. Amanjit Singh Gill V.P.O. Mazari, Tehsil Balachaur, RM/BDC/123 98721-66086 238236 Distt.SBS Nagar-144526 5 Sh. Avtar Ram S/o V.P.O.Bachhouri,Balachaur RM/BDC/170 94634-71907 01885-273231 Sh.Darshan Ram Distt.SBS Nagar-144526 6 Sh. Amarjit Singh C.M.C. Chandigarh Road, RM/BDC/073 01823-223390 250207 Nawanshahr-144514 94172-63390 508335 7 Sh. Amarjit Singh V.P.O. Malla Bedian, (Aur) RM/BDC/096 01823-245631 245533, 246733 S/o Sh.Gulzara Ram Distt.SBS Nagar-144417 94173-04523 8 Sh. Amrik Singh Kaler V.P.O Parzian, Tehsil–Nakodar, RM/BDC/083 0181-2282402 01821-274250 Jalandhar 94176-38141 9 Sh. Amrik Singh Katariya V.P.O. Mukandpur, RM/BDC/048 9357811180 276211 Teh. & Distt.SBS Nagar-144507 10 Mrs. Anita Punj I.P.S. A.I.G Personnel,Chandigarh RM/BDC/099 11 Sh. Arun Kumar Sharma H. No. 1690, Ward No. 7, RM/BDC/119 9463471930 01885-220848 Sarafan Bazar,Teh. Balachaur, Distt.S.B.S Nagar-144521 12 Sh. Arun Sharma H.No. 264, Prem Nagar, RM/BDC/019 9872011898 01823 - 220898, Nawanshahr-144514 224098 13 Sh. -

Criminal Intelligence Gazette for the Month of December 2019

Criminal Intelligence Gazette For The Month Of December 2019 Prepared By State Crime Records Bureau, Punjab INDEX Sr. No. PART No. DESCRIPTION PAGE 1. PART I-A MISSING PERSONS 1-53 2. PART I-B TRACED PERSONS 54-69 3. PART II UNIDENTIFIED DEAD BODIES 70-85 4. PART III WANTED PERSONS 86 5. PART IV-A STOLEN VEHICLES 87-103 6. PART IV-B RECOVERED VEHICLES 104-112 7. PART V INTERSTATE CRIMINAL GANGS 113-119 8. PART VI MISSING DOCUMENTS 120-125 9. PART VII-A PROCLAIMED OFFENDERS 126-129 (U/s 82/83 Cr. P.C.) 10. PART VII-B ABSCONDERS (U/s 299 Cr. P.C.) 130-136 PART I-A MISSING PERSONS S. NAME AND DESCRIPTION OF DDR/FIR No. PS /DISTT. PHOTOGRAPH No. ADDRESS OF MISSING PERSON & DATE THE MISSING PERSON 1. Harjinder Age 27 Years 142 Mohkampura Singh S/o Height 6’ 0” 05-12-2019 Commission- Jagtar Singh Hair Black U/s 346 IPC erate Amritsar R/o 3072, Wearing Blue Mohalla Khem Colour Jean, White Singh Tungpai Shirt & Light Cream Batala Road, Sweater. Amritsar. 2. Balbir Singh Age 57 Years 16 Majitha Road S/o Hazara Height 5’ 8” 23-12-2019 Commission- Singh R/o 2, Hair Black/White erate Amritsar Medical Wearing Black Enclave, Colour Pent & Amritsar. White Shirt. 3. Sohit S/o Age 33 Years 35 Majitha Road Swaran Pal R/o Height 6’ 0” 08-12-2019 Commission- Subhash Nagar Hair Black erate Amritsar Talwara. Wearing Blue Colour Jearsy, Red & White Shoe. 4. Sahildeep Age 19 Years 41 Sadar Sahota S/o Height 5’ 10” 19-12-2019 Commission- Sandeep Hair Black erate Amritsar Kumar R/o Wearing Blue 222, Dimond Colour Jean & Avenue White Colour Shirt Majitha Road, Amritsar. -

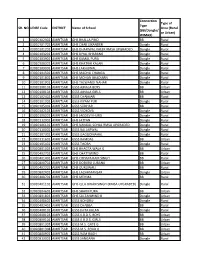

BB/Dongle/ WIMAX) Type of Area (Rural Or Urban

Connection Type of Type SR. NO UDISE Code DISTRICT Name of School Area (Rural (BB/Dongle/ or Urban) WIMAX) 1 03020302302 AMRITSAR GHS BHALLA PIND BB Rural 2 03020101702 AMRITSAR GHS CHAK SIKANDER Dongle Rural 3 03020101202 AMRITSAR GHS DHARIWAL KALER RMSA UPGRADED Dongle Rural 4 03020103202 AMRITSAR GHS DIYAL BHARANG Dongle Rural 5 03020103902 AMRITSAR GHS KAMAL PURA Dongle Rural 6 03020300302 AMRITSAR GHS KHATRAI KALAN Dongle Rural 7 03020109002 AMRITSAR GHS LAKHUWAL Dongle Rural 8 03020104502 AMRITSAR GHS MADHU CHANGA Dongle Rural 9 03020101802 AMRITSAR GHS MOHAN BHADIARN Dongle Rural 10 03020101902 AMRITSAR GHS TALWANDI NAHAR Dongle Rural 11 03020100103 AMRITSAR GSSS AJNALA BOYS BB Urban 12 03020100104 AMRITSAR GSSS AJNALA GIRLS BB Urban 13 03020102402 AMRITSAR GSSS CHAMIARI BB Rural 14 03020101002 AMRITSAR GSSS KIYAM PUR Dongle Rural 15 03020105002 AMRITSAR GSSS SUDHAR BB Rural 16 03020102103 AMRITSAR GSSS VICHOVA Dongle Rural 17 03020108202 AMRITSAR GHS JAGDEV KHURD Dongle Rural 18 03020112002 AMRITSAR GHS JATTAN Dongle Rural 19 03020106102 AMRITSAR GHS NANGAL SOHAL RMSA UPGRADED Dongle Rural 20 03020110002 AMRITSAR GSSS BALLARWAL Dongle Rural 21 03020107302 AMRITSAR GSSS GAGGOMAHAL Dongle Rural 22 03020111602 AMRITSAR GSSS RAMDAS BB Urban 23 03020105402 AMRITSAR GSSS THOBA Dongle Rural 24 03020801003 AMRITSAR GHS BHAGTA WALA G BB Urban 25 03020402702 AMRITSAR GHS CHATTIWIND BB Rural 26 03020401402 AMRITSAR GHS CHHAPA RAM SINGH BB Rural 27 03020800702 AMRITSAR GHS DOBURJI LUBANA BB Urban 28 03020402202 AMRITSAR GHS GURUWALI BB Rural 29 03020802402 AMRITSAR GHS LACHHMANSAR Dongle Urban 30 03020400702 AMRITSAR GHS MEHMA BB Rural 31 03020401102 AMRITSAR GHS QILA JIWAN SINGH (RMSA UPGRADED) Dongle Rural 32 03020804602 AMRITSAR GHS SHARIFPURA BB Urban 33 03020801803 AMRITSAR GHS SULTANWIND B Dongle Urban 34 03020408602 AMRITSAR GSSS BOHORU Dongle Rural 35 03020402402 AMRITSAR GSSS CHABBA BB Rural 36 03020400102 AMRITSAR GSSS JHITA KALAN Dongle Rural 37 03020800103 AMRITSAR GSSS K.B.D.S. -

School/College

POLICE DEPARTMENT DISTT. S.B.S. NAGAR SCHOOL/COLLEGE SR.NO NAME OF SCHOOL/COLLEGE PLACE Telephone TILL WHICH CLASS . 1. R.K.ARYA COLLEGE RAHON ROAD 01823-220031 MA+BA 2. B.L.M.GIRLS COLLEGE RAHON ROAD 01823-220026 BA+MA 3. K.C.ENG.COLLEGE KARYAM ROAD 01823-.503836,232499 MA 4. I.T.I CHANDIGARH ROAD 01823-222020 5. SHIVALIK PUBLIC SCHOOL CHANDIGARH ROAD 98140-08886 10+2 6. ADARSH BAL VIDALYA NAWAN SHAHAR 01823-222132,222236 10+2 7. K.C. PUBLIC SCHOOL KARYAM ROAD 9914100585 10+2 8. RALLAN MALL BHUCHAR NAWAN SHAHAR 01823-221195,222195 MATRIC D.A.B.PUBLIC SCOOL 9. RED ROSE PUBLIC SCHOOL PANDORA MOHALLA NSR 01823-220665 MATRIC 10. DR. ASHA NAND ARYA MODEL NAWAN SHAHAR 9417633629 10+2 SCHOOL 11. DOABA ARYA SEN. NAWAN SHAHAR 9915715543 10+2 SEC.SCHOOL 12. PARKASH MODEL SEN. SEC. NAWAN SHAHAR 01823-220414 10+2 SCHOOL 13. TAGORE MODEL SEN.SEC. NAWAN SHAHAR 01823-225372 MATRIC SCHOOL 14. DOABA SIKH NATIONAL SEN. NAWAN SHAHAR 01823-220078 10+2 SEC. 15 BABA BAJIR KHALSHA GIRLS NAWAN SHAHAR 01823-221611 MATRIC SCHOOL 16. Govt. Elementary School Uttal 01823-254296 1st To 8th 98782-21721 17 Govt. High School Mirpur jattan 9646233502 1st To 10th 18 Govt. Elimentry School Chrran 01823-244311 1st To 5th 19 Govt. Elementary School Majhur 94171-87437 1st To 8th 20 Govt. Elementary School Dupalpur 94641-27454 1st To 5th 21 Govt. Elementary School Ramgarh 94172-62863 1st To 5th 22 Govt. Elementary School Ranewal 94176-74632 1st To 8th 23 Govt. -

POLICE DEPARTMENT DISTT SBS NAGAR LIST of PROCLAIMED OFFENDER's 82/83 Crpc.(PO's) S NO NAME & ADDRESS of PO FIR NO.,DATE

POLICE DEPARTMENT DISTT SBS NAGAR LIST OF PROCLAIMED OFFENDER's 82/83 CrPC.(PO’s) S NAME & ADDRESS OF PO FIR NO.,DATE, U/S & PS PS P.O DATE HEAD OF CRIME RESIDENCE NO DISTT PS CITY NAWANSHAHAR TERRORIST CASES P.Os 1 GURTIRATH SINGH S/O FIR No .44 DT.27/07/1992 CITY NSR 05/06/1993 HEINOUS HOME DISTT SANTOKH SINGH V. MUSAPUR 307/34 IPC 24/54/59 A ACT PS BANGA DISTT. SBS NAGAR 3/4 TDA(P) ACT PS CITY STATE PUNJAB NAWANSHAHAR 2.FIR No.109 DT.02/10/1991 CITY NSR 19/05/1998 307/148/149 IPC 3/4/5 TDA (P) ACT PS CITY NAWANSHAHAR 2 SATNAM SINGH @ SATTI S/O FIR No .12 DT.02/01/1993 CITY NSR 13/11/96 HEINOUS HOME DISTT MALKIAT SINGH V. BHANGAL 212/216-A IPC 5/6 TDAP PS KALAN PS SADAR NSR DISTT. CITY NAWANSHAHAR SBS NAGAR STATE PUNJAB 2.FIR No.90 DT.29/04/1987 CITY NSR 01/09/1997 18/61/85 NDPS ACT 25/54/ 56 A ACT PS CITY NAWANSHAHAR 3 GURNEK SINGH @ MEEKA S/O FIR No .148 DT.21/06/1987 CITY NSR 15/03/1992 HEINOUS OUT OF DISTT PRITAM SINGH V. MEHRAMPUR 302/307/353/186 IPC 3/4 PS NAKODER TDAP ACT PS SADAR DISTT.JALANDHAR STATE NAWANSHAHAR PUNJAB TO CITY NSR 4 GURNEK SINGH S/O SOHAN FIR No .180 DT.21/11/1989 CITY NSR 09/11/1991 HEINOUS HOME DISTT SINGH V. HIYALA PS SADAR 302/34 IPC 25/54/59 A ACT NSR DISTT. -

List of 3500 VLE Cscs in Punjab

Sr No District Csc_Id Contact No Name Email ID Subdistrict_Name Village_Name Village Code Panchayat Name Urban_Rural Kiosk_Street Kiosk_Locality 1 Amritsar 247655020012 9988172458 Ranjit Singh [email protected] 2 Amritsar 479099170011 9876706068 Amot soni [email protected] Ajnala Nawan Pind (273) 37421 Nawan Pind Rural Nawanpind Nawanpind 3 Amritsar 239926050016 9779853333 jaswinderpal singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Dolonangal (33) 37710 Baba Sawan Singh Nagar Rural GALI NO 5 HARSANGAT COLONY BABA SAWAN SINGH NAGAR 4 Amritsar 677230080017 9855270383 Barinder Kumar [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000532 \N Urban gali number 5 vishal vihar 5 Amritsar 151102930014 9878235558 Amarjit Singh [email protected] Amritsar -I Abdal (229) 37461 Abdal Rural 6 Amritsar 765534200017 8146883319 ramesh [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000532 \N Urban gali no 6 Paris town batala road 7 Amritsar 468966510011 9464024861 jagdeep singh [email protected] Amritsar- II Dande (394) 37648 Dande Rural 8 Amritsar 215946480014 9569046700 gursewak singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Saido Lehal (164) 37740 Saido Lehal Rural khujala khujala 9 Amritsar 794366360017 9888945312 sahil chabbra [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000540 \N Urban SARAIN ROAD GOLDEN AVENUE 10 Amritsar 191162640012 9878470263 amandeep singh [email protected] Amritsar -I Athwal (313) 37444 \N Urban main bazar kot khalsa 11 Amritsar 622551690010 8437203444 sarbjit singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Butala (52) 37820 Butala Rural VPO RAJPUR BUTALA BUTALA 12 Amritsar 479021650010 9815831491 hatinder kumar [email protected] Ajnala \N 9000535 \N Urban AMRITSAR ROAD AJNALa 13 Amritsar 167816510013 9501711055 Niketan [email protected] Baba Bakala \N 9000545 \N Urban G.T. -

S.No Block District* Name Age* Sex* Address* Contact Number* Passport Number* Traceable* Country of Visit* City Other Than China

Under Passport Date of leaving Date of Arrival from SOURCE OF Date of Receipt of Observation Ever developed symptoms (during Currently Date of Hospital Where Date of Discharge Sample Date of Sample Result of Lab where samples Home If Migrated (Out of Other State Date of #Helper Table - S.No Block District* Name Age* Sex* Address* Contact Number* Traceable* Country of Visit* City Other than China* Provinces in China * Current Status* surveillance/Migrated/Surveillance Remarks* Number* China* Affected Country* INFORMATION* Information* started from* surveillance period)* Hospitalised* Hospitalisation* isolated/admitted* from Hospital* Collected* Collection* Sample* sent* Quarantined/Hospitalized* India/Other State)* Name* Reporting* Labs completed* 1 Saroya CRAMPTON ELIZABETH MARY 48 Female S/O SATPAL CHECHI VPO JEETPUR,THE BALACHAUR,DISTT SBS NAGAR 99143-31646 LL926579 Yes 1 HOUR STAY IN SINGAPUR NEWZEALAND NEWZEALAND NO 2/24/2020 State Health Authority 28.02.2020 2/29/2020 No Asymptomatic No NO NO NO NO NO NO NO Under surveillance Home Quarantined NA NA the pessenger had not visited china, by Singapore 2 Sujjon DOSANJH SURINDER KAUR VILL BHOOTAN, BANGA , CITY - SBS NAGAR 9501482782 512662251 Yes Dubai Dubai Dubai NO 3/12/2020 State Health Authority 3/21/2020 3/22/2020 No Asymptomatic NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO Under surveillance Home Quarantined NA NA List-72 3 Banga GILL SIMARPREET KAUR 14 F 2729 GANDHI NAGAR , CITY - BANGA 9876772783 AK553310 Yes Canada Canada Canada NO 3/12/2020 State Health Authority 3/21/2020 3/22/2020 No Asymptomatic -

DISTRICT NAWAN SHAHER Sr. No. Name of Block Name of Village

DISTRICT NAWAN SHAHER Sr. Name of Block Name of Village Name of Grampanchyat Hadbast No. No. AUR 1. Aur Aur 211 2. Burj Tehalds Burj Tehalds 292 3. Balowal Balowal 193 4. Barnala Khurd Barnala Khurd 221 5. Bharo Mazara Bharo Mazara 62 6. Bajon Bajon 184 7. Bazidpur Bazidpur 217 8. 1. Bakhlaur Bakhlaur 199 2. Mahal Badowal 3. Mahal Khairabad 200 9. Bairsal Bairsal 274/76 10. Bharat Kalan Bharat Kalan 219 11. Bharta Khurd Bharta Khurd 220 12. Buhara Buhara 176 13. Bahadurpur Bahadurpur 214 14. Baghora Baghora 68 15. Begowal Begowal 289 16. Chak Dana Chak Dana 202 17. Chahal Kalan Chahal Kalan 196 18. Chahal Khurd Chahal Khurd 115 19. Daryapur Daryapur 278 20. 1. Dodhala Dodhala 216 2. Saidpur Than 215 21. Ferozepur Ferozepur 89 22. Garcha Garcha 175 23. Garhi Ajit Singh Garhi Ajit Singh 208 24. Garhi Bharti Garhi Bharti 218 25. Guna Chaur Guna Chaur 91 26. Garh Bhadana Garh Bhadana 213 27. Gehal Mazari Gehal Mazari 90 28. 1. Garopur Garopur 210 2. Baloni 209 29. Hakimpur Hakimpur 195 30. 1. Herian Herian 188 2. Surapur Theh 190 31. Jagatpur Jagatpur 69 1 Sr. Name of Block Name of Village Name of Grampanchyat Hadbast No. No. 32. 1. Jalah Majra Jalah Majra 286 2. Jhungian 285 33. Jhingran Jhingran 183 34. Kahlon Kahlon 222 35. Kang Kang 169 36. Kharkoowal Kharkoowal 287 37. Khoja Khoja 284 38. Kamam Kamam 187 39. 1. Khurd Khurd 203 2. Shibdialpur 204 40. Lal Mazara Lal Mazara 189 41. Lidhar Kalan Lidhar Kalan 67 42. -

2020032617.Pdf

Hospital Where Date of Under Date of leaving Date of Arrival from Affected Date of Receipt of Observation started Ever developed symptoms (during Currently Date of Sample Date of Sample Result of Lab where samples Home If Migrated (Out of Other State Date of S.No Block District* Name Age* Sex* Address* Contact Number* Passport Number* Traceable* Country of Visit* City Other than China* Provinces in China * SOURCE OF INFORMATION* Current Status* isolated/admitted Discharge from surveillance/Migrated/Surveillance Remarks* China* Country* Information* from* surveillance period)* Hospitalised* Hospitalisation* Collected* Collection* Sample* sent* Quarantined/Hospitalized* India/Other State)* Name* Reporting* * Hospital* completed* 1 NSR NEHA 26 Female h.no. b-14/348, SBS NAGAR LAROYIAN MOHALLA 144514 98141-51288 J8698032 Yes 3 hr stay at China Canada China 43857 43858 State Health Authority 43880 43880 NO Asymptomatic NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO Under surveillance Home Quarantined Out of India NA NA Observation period completed 2 NSR ARORA PRAYAG 3 Male hno. b/14,348 CITY NSR laroyian mohalla 144514 98141-51288 N3107132 Yes 3 hr stay at China Canada China 43857 43858 State Health Authority 43880 43880 NO Asymptomatic NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO Under surveillance Home Quarantined Out of India NA NA Observation period completed 3 NSR ARORA ASHISH 27 Male b/14,348 NAWANSHAHR laroyian mohalla 144514 98141-51288 J6786023 Yes 3 hr stay at China Canada China 43857 43858 State Health Authority 43880 43880 NO Asymptomatic NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO Under surveillance