Altica Tombacina</Em>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Females of the Finnish Species of Altica Muller (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae)

© Entomologica Fennica. 31.V.1993 Identification of females of the Finnish species of Altica Muller (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) Esko Kangast & Ilpo Rutanen Kangas, E. & Rutanen, I. 1993: Identification offemales of the Finnish species of Altica Muller (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae).- Entomol. Fennica 4:115- 129. The possible use of secondary genitalia (styles and spiculum ventrale) for the identification of females of Altica is investigated. Two identification keys are presented, one using both morphological and secondary genital characters and one using secondary genital characters only. The Finnish species are reviewed: A. cirsii Israelson is deleted, and A. quercetorum saliceti Weise and A. carduorum (Guerin-Meneville) are added to the Finnish list, now comprising 12 species. The geographical and temporal aspects of the distribution of the species in Finland is shown on UTM maps. Ilpo Rutanen, Water and Environment Research Institute, P.O.Box 250, FIN- 00101 Helsinki, Finland 1. Introduction Thus far the distinctive characters of female Identification keys available today for identifying genitalia have been very seldom used for the females of the genus Altica Muller are often mainly identification of species. Spett & Levitt (1925, based on distinctive morphological characters (e.g. 1926) in their investigations on the significance Lindberg 1926, Hansen 1927). In the case of males, of the female spermatheca (receptaculum semi differences in the aedeagus have also been taken nis) of Chrysomelidae as a taxonomic character into consideration (e.g. Heikertinger 1912, Hansen also explained the structure of the spermatheca 1927, Mohr 1966). However, the rarity of males of Altica. Kevan (1962) was the first author to among the most common Finnish species restricts take into consideration the styles as well as the the possibility of using the characteristics of male spermatheca as a distinctive specific characteris genitalia for specific identification (comp. -

Biological Control of Paterson's Curse with the Tap-Root Flea Beetle (DSE Vic)

January 1999 Biological control of Paterson's curse LC0155 with the taproot flea beetle ISSN 1329-833X Keith Turnbull Research Institute, Frankston Common and scientific names laying within a few weeks. Some adults may survive until late in spring. Paterson’s curse taproot flea beetle Eggs are laid on and around the crown of the plant. Larvae Longitarsus echii Koch (grubs) hatch after about three weeks, depending on the Family Chrysomelidae, leaf beetles environmental temperature. Background The larvae initially feed on the plant crown and leaf stalks, and then descend into the taproot where they feed Paterson’s curse (Salvation Jane), Echium plantagineum, is internally. After three months the larvae leave the root and a noxious weed of European origin found through much of pupate in the soil. Around one month later, they transform Victoria. It is a Regionally Controlled Weed in all into adults, which remain inactive in earthen cells in the Victorian Catchment and Land Protection Regions except soil until winter. Mallee. Landholders in these areas must take all reasonable steps to control and prevent the spread of this weed on their land and the roadsides which adjoin their land. A national program for biological control of Paterson’s curse involves the establishment of populations of the weed’s natural enemies and the redistribution of them to other sites as populations increase. A cooperative project between CSIRO and DNRE has led to the release of the Paterson’s curse taproot feeding flea beetle, Longitarsus echii, in Victoria. The flea beetle has been tested to ensure it is specific to Paterson’s curse and presents no danger to native plants or plants of economic importance. -

Corn Flea Beetle

Pest Profile Photo credit: North Central Branch-Entomological Society of America, UNL-Entomology Extension Common Name: Corn flea beetle Scientific Name: Chaetocnema pulicaria Order and Family: Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance white have a pointy end Egg ~0.35 darken slightly in color before hatching white slimly shaped Larva/Nymph < 9 cylindrical prothorax and last abdominal segment are slightly darkened small shiny black Adult < 2 enlarged hind legs white Pupa (if soft in texture applicable) gets dark before development is complete Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Chewing mouthparts Host plant/s: Corn is the preferred host plant, but they are also found on a number of different grass types, oats, Timothy, barley and wheat. Description of Damage (larvae and adults): The adult corn flea beetle injures corn plants by removing leaf tissue and by transmitting pathogenic bacteria. Injury by the adults appears as scratches in the upper and lower surfaces of the leaf, usually parallel to the veins. They feed on both the upper and the lower epidermis of corn leaves, but they do not chew completely through the leaves. The scratches rarely result in economy injury. The leaves of severely injured plants appear whitish or silvery. More importantly, the beetles transmit the bacterium Erwinia stewartia, the casual organism of Stewart’s wilt, to susceptible varieties of corn. Field corn infested with Stewart’s disease will show little sign of disease until late in the summer when numerous leaf lesions will appear on the leaves. The result is often small ears or no ears at all. -

CDA Leafy Spurge Brochure

Frequently Asked Questions About the Palisade Insectary Mission Statement How do I get Aphthona beetles? You can call the Colorado Department of We are striving to develop new, effective Agriculture Insectary in Palisade at (970) ways to control non-native species of plants 464-7916 or toll free at (866) 324-2963 and and insects that have invaded Colorado. get on the request list. We are doing this through the use of biological controls which are natural, non- When are the insects available? toxic, and environmentally friendly. We collect and distribute adult beetles in June and July. The Leafy Spurge Program In Palisade How long will it take for them to control my leafy spurge? The Insectary has been working on leafy Biological Control You can usually see some damage at the spurge bio-control since 1988. Root feeding point of release the following year, but it flea beetles are readily available for release of typically takes three to ten years to get in early summer. Three other insect species widespread control. have been released and populations are growing with the potential for future Leafy Spurge What else do the beetles feed on? distribution. All of the leafy spurge feeding The beetles will feed on leafy spurge and insects are maintained in field colonies. cypress spurge. They were held in Additional research is underway to explore quarantine and tested to ensure they would the potential use of soilborne plant not feed on other plants before they were pathogens as biocontrol agents. imported and released in North America What makes the best release site? A warm dry location with moderate leafy spurge growth is best. -

The Life History and Management of Phyllotreta Cruciferae and Phyllotreta Striolata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), Pests of Brassicas in the Northeastern United States

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2004 The life history and management of Phyllotreta cruciferae and Phyllotreta striolata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), pests of brassicas in the northeastern United States. Caryn L. Andersen University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Andersen, Caryn L., "The life history and management of Phyllotreta cruciferae and Phyllotreta striolata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), pests of brassicas in the northeastern United States." (2004). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 3091. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/3091 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LIFE HISTORY AND MANAGEMENT OF PHYLLOTRETA CRUCIFERAE AND PHYLLOTRETA STRIOLATA (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE), PESTS OF BRASSICAS IN THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Thesis Presented by CARYN L. ANDERSEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE September 2004 Entomology © Copyright by Caryn L. Andersen 2004 All Rights Reserved THE LIFE HISTORY AND MANAGEMENT OF PHYLLOTRETA CRUCIFERAE AND PHYLLOTRETA STRIOLATA (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE), PESTS OF BRASSICAS IN THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Thesis Presented by CARYN L. ANDERSEN Approved as to style and content by: Tt, Francis X. Mangan, Member Plant, Soil, and Insect Sciences DEDICATION To my family and friends. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisors, Roy Van Driesche and Ruth Hazzard, for their continual support, encouragement and thoughtful advice. -

Agent: Flea Beetle Longitarsus Jacobaeae Plant Species Attacked: Tansy Ragwort Senecio Jacobaea

Agent: Flea beetle Plant species attacked: Tansy ragwort Longitarsus jacobaeae Senecio jacobaea Impact on target plant: The adults feed on the foliage and cause significant mortality of rosettes during the winter months. The larvae feed in the roots and the leaf petioles. Collection and release: Use a motorized vacuum unit to suck adults from rosettes in the fall. Releases of 100-500 are recommended. Because the beetle is so widespread, redistribution in western Oregon is unnecessary. Distribution: The beetle has been released in 24 Oregon counties and is established in 21. History: The ragwort flea beetle Longitarsus jacobaeae, introduced in 1971, the workhorse of the ragwort program, has reduced ragwort density by 95% in western Oregon. The combination of the cinnabar moth and flea beetle has nearly eliminated large outbreaks of flowering ragwort in many areas in western Oregon. Occasional flare-ups of ragwort reoccur, but the insects usually control the plants within a couple of years. Plant competition is an important factor in maintaining biocontrol of ragwort. In 2007, cooperative research project with Dr. Mark Schwarzländer and staff (U of ID), looked into the feasibility of using the Swiss biotype of the flea beetle to control infestations in Eastern Oregon, where the Italian biotype is ineffective. Releases of the Swiss biotype were made in Umatilla County in 2007 and in Umatilla and Union Counties in 2008. The insect readily established in similar habitats in Idaho and Montana. Monitoring in 2010 and 2011 for the Swiss biotype did not show that that the beetles established in eastern Oregon. Flea beetle populations can exist where host densities are low. -

A General Study of the Mint Flea-Beetle, Longitarus Waterhousei Kutsch

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Leung, Yuk Viaan . S. Eitomo1ogy ---------------------- for the -------- in --------------- (Naine) (Degree) (Majr) La'r 11th 1938 Date Thesis presented-- --------- Title ------ Abstract APProved:L (Major Professor) The nii.nt flea-beetle, Lonitarsuswaterhouei,is a new dilsoovery in Ore:on. It mi:ht have been brought in in the infested roots froi Michigan. As far a is iciown the beetle attacks the raint family only. The roatest damage is done by larvae which feed on the epidermis of the small rooUets and tunnel through the large roots in the spring, causing the abnornial growth of the plant or killing the plant coplete1y ir. sorne cases. The adult beetles feed on the epidermis of the fo1iace and frequently riddle the loaves vth tiny holes. There is but one generation a year. The insects overwinter in the egg stage. The adult beetles appeared in the field sometime in July. The females begin to deposit eggs a month or so after emergence. The larvae will hatch at any time after spring approaches. After the larvae are fully developed, they leave the roots to pupate in the soll. The stae thkes about 26 days. Several control methods are suyested, A GEITERíL STUDY OF TI MINT FLEA-BEETLE, LONGITRSUS VATEHHOUSEI J11TSCH by YUK iAN LEUNG A THESIS submitted to the OREGON STATE GRICULTURL COLLEGE in partial fulfillment of the reauirements for the degree of lIASTER OF SCIENCE May 1938 APPROVED: Head of Department of Entomology In Charge of i:ajor Chairman of School Graduate Coniittee Chairman of College Graduate Council TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......... -

Flea Beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Associated with Purple Loosestrife, Lythrum Salicaria, in Russia

Flea beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, in Russia Margarita Yu. Dolgovskaya,1 Alexander S. Konstantinov,2 Sergey Ya. Reznik,1 Neal R. Spencer3 and Mark G. Volkovitsh1 Summary Purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria L., has become one of the more troublesome wetland exotic inva- sive weeds in Canada and the United States from initial introductions some 200 years ago. In the US, purple loosestrife has spread to most of the contiguous 48 states (no records from Florida) with the highest density in the north-east. L. salicaria is now recorded in all Canadian provinces with the excep- tion of Yukon and the North-West Territories. A biological control effort begun in the 1970s resulted in the introduction in the 1990s of four insect species: a root-boring and a flower-feeding weevil, and two leaf beetle species (both adults and larvae are leaf feeders). As long-term impact assessments of these introductions are conducted, additional research is looking at other potential biological control agents, particularly insect species attacking both leaves and roots of the target plant. Thus, flea beetles with root-feeding larvae and leaf-feeding adults may be of value. Purple loosestrife is widespread in Russia in wet meadows, riverbanks and other moist habitats from the Baltic region to eastern Russia. Literature searches, studies of museum collections and ecological observations in the field and the laboratory suggest that a number of flea beetle species feed on L. salicaria, of which the oligophagous Aphthona lutescens with a flexible life cycle and two-fold impact on the host (larvae are root-borers and adults are leaf feeders) appears to be a particularly promising biocontrol agent. -

Flea Beetles

Problem: Flea Beetles Hosts: Watermelons, pumpkins, peas, beans, eggplants, sweet potatoes, beets, spinach, strawberries and potatoes. Description: "Flea beetle" is a generic name applied to many species of small jumping beetles commonly seen early in the gardening season. Some species are general feeders while others have a more restricted host range. All flea beetle life stages are completed underground. Only the adults are commonly seen by gardeners and vegetable producers. Flea beetles may be somewhat elongate to oval in shape, and vary in color, pattern, and size. For instance, potato flea beetles (Epitrix cucumeris) tend to be more oval, blackish, and about 1/16-inch long. Striped flea beetles (Phyllotreta striolata) are more elongate and dark with yellowish crooked stripes, and measure about 1/12-inch long. Spinach flea beetles (Disonycha xanthomelaena) are both oval and elongate. They have a black head, antennae and legs. The collar behind the head is yellow to yellowish-orange. Wing covers have blackish-blue luster. They approach 1/5 inch in body length. With most species of flea beetle, the adults overwinter underground or beneath plant debris. During April and May, they become active, mate, and deposit eggs. Egg laying varies depending upon species. Some deposit individual eggs while others deposit them in clusters. Egg sites may be in soil, on leaves, on leaf petioles, or within holes chewed into stems. Eggs typically hatch in 10 days. Larval and pupal development take place during the summer. "New" adults emerge and feed during late summer and fall before seeking overwintering sites. Larvae feeding on underground portions of plants may result in decreased plant vigor. -

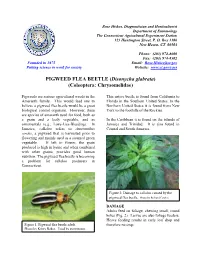

PIGWEED FLEA BEETLE (Disonycha Glabrata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)

Rose Hiskes, Diagnostician and Horticulturist Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8600 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PIGWEED FLEA BEETLE (Disonycha glabrata) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Pigweeds are serious agricultural weeds in the This native beetle is found from California to Amaranth family. This would lead one to Florida in the Southern United States. In the believe a pigweed flea beetle would be a great Northern United States it is found from New biological control organism. However, there York to the foothills of the Rockies. are species of amaranth used for food, both as a grain and a leafy vegetable, and as In the Caribbean it is found on the islands of ornamentals (e.g., Love-Lies-Bleeding). In Jamaica and Trinidad. It is also found in Jamaica, callaloo refers to Amaranthus Central and South America. viridis, a pigweed that is harvested prior to flowering and mainly used as a steamed green vegetable. If left to flower, the grain produced is high in lysine and when combined with other grains, provides good human nutrition. The pigweed flea beetle is becoming a problem for callaloo producers in Connecticut. Figure 2. Damage to callaloo caused by the pigweed flea beetle. Photo by Richard Cowles. DAMAGE Adults feed on foliage, chewing small, round holes (Fig. 2). Larvae are also foliage feeders. Heavy feeding results in early leaf drop and Figure 1. -

Specific Composition of Flea Beetles (Phyllotreta Spp ), the Dynamics of Their Number on Summer Rape

Agronomy Research 1(2), 123–130, 2003 Specific composition of flea beetles (Phyllotreta spp ), the dynamics of their number on the summer rape (Brassica napus L. var. oleifera subvar. annua) Mascot K. Hiiesaar¹, L. Metspalu¹, P. Lääniste² and K. Jõgar¹ ¹Institute of Plant Protection, Estonian Agricultural University, Kreutzwaldi 64, 51014, Tartu, Estonia; e-mail: [email protected] ²Institute of Field Crop Husbandry, Estonian Agricultural University, Kreutzwaldi 64, 51014, Tartu, Estonia Abstract. The specific composition of the flea beetle Phyllotreta spp (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), time of its appearance and dynamics of its number on the summer rape cultivar Mascot were determined. During the observation period, 6 species of flea beetles were found: Phyllotreta undulata Kutsch., Ph. nemorum L., Ph. vittata (Ph. striolata), Ph. nigripes F. Ph. atra and Ph. vittula. First flea beetles appeared at the time of the sprouting of rape plants. In the course of the entire observation period, the most numerous of these was the small striped flea beetle Ph. undulata. Proportion of the other species not often exceeded 10%. Very warm and dry weather following the sprouting of plants caused a rapid increase in the number of the pests and the maximum number was reached in a short time. A somewhat larger number of beetles was found on the edge plots. The field was sprayed three times, using Fastac (alphacypermethrin). Although after the first spraying the number of pests had decreased to almost zero, one week later the number of beetles began to rise again. Ten days after the spraying, the number of pests in the control and the sprayed variant had become equal, 2.0 and 2.2 individuals per plant. -

Flea Beetles

E-74-W Vegetable Insects Department of Entomology FLEA BEETLES Rick E. Foster and John L. Obermeyer, Extension Entomologists Several species of fl ea beetles are common in Indiana, sometimes causing damage so severe that plants die. Flea beetles are small, hard-shelled insects, so named because their enlarged hind legs allow them to jump like fl eas from plants when disturbed. They usually move by walking or fl ying, but when alarmed they can jump a considerable distance. Most adult fl ea beetle damage is unique in appearance. They feed by chewing a small hole (often smaller than 1/8 inch) in a leaf, moving a short distance, then chewing another hole and so on. The result looks like a number of “shot holes” in the leaf. While some of the holes may meet, very often they do not. A major exception to this characteristic type of damage is that caused by the corn fl ea beetle, which eats the plant tissue forming narrow lines in the corn leaf surface. This damage gives plants a greyish appearance. Corn fl ea beetle damage on corn leaf (Photo Credit: John Obermeyer) extent of damage is realized. Therefore, it is very important to regularly check susceptible plants, especially when they are in the seedling stage. Most species of fl ea beetles emerge from hibernation in late May and feed on weeds and other plants, if hosts are not available. In Indiana, some species have multiple generations per year, and some have only one. Keeping fi elds free of weed hosts will help reduce fl ea beetle populations.