Hook Norton (June 2021) • Settlement Etc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

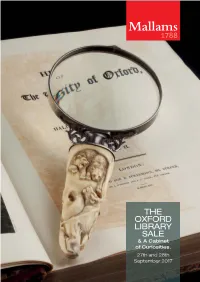

THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & a Cabinet of Curiosities

Mallams 1788 THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & A Cabinet of Curiosities. 27th and 28th September 2017 Chinese, Indian, Islamic & Japanese Art One of a pair of 25th & 26th October 2017 Chinese trade paintings, Final entries by September 27th 18th century £3000 – 4000 Included in the sale For more information please contact Robin Fisher on 01242 235712 or robin.fi[email protected] Mallams Auctioneers, Grosvenor Galleries, 26 Grosvenor Street Mallams Cheltenham GL52 2SG www.mallams.co.uk 1788 Jewellery & Silver A natural pearl, diamond and enamel brooch, with fitted Collingwood Ltd case Estimate £6000 - £8000 Wednesday 15th November 2017 Oxford Entries invited Closing date: 20th October 2017 For more information or to arrange a free valuation please contact: Louise Dennis FGA DGA E: [email protected] or T: 01865 241358 Mallams Auctioneers, Bocardo House, St Michael’s Street Mallams Oxford OX1 2EB www.mallams.co.uk 1788 BID IN THE SALEROOM Register at the front desk in advance of the auction, where you will receive a paddle number with which to bid. Take your seat in the saleroom and when you wish to bid, raide your paddle and catch the auctioneer’s attention. LEAVE A COMMISSION BID You may leave a commission bid via the website, by telephone, by email or in person at Mallams’ salerooms. Simply state the maximum price you would like to pay for a lot and we will purchase it for you at the lowest possible price, while taking the reserve price and other bids into account. BID OVER THE TELEPHONE Book a telephone line before the sale, stating which lots you would like to bid for, and we will call you in time for you to bid through one of our staff in the saleroom. -

OXONIENSIA PRINT.Indd 253 14/11/2014 10:59 254 REVIEWS

REVIEWS Joan Dils and Margaret Yates (eds.), An Historical Atlas of Berkshire, 2nd edition (Berkshire Record Society), 2012. Pp. xii + 174. 164 maps, 31 colour and 9 b&w illustrations. Paperback. £20 (plus £4 p&p in UK). ISBN 0-9548716-9-3. Available from: Berkshire Record Society, c/o Berkshire Record Offi ce, 9 Coley Avenue, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 6AF. During the past twenty years the historical atlas has become a popular means through which to examine a county’s history. In 1998 Berkshire inspired one of the earlier examples – predating Oxfordshire by over a decade – when Joan Dils edited an attractive volume for the Berkshire Record Society. Oxoniensia’s review in 1999 (vol. 64, pp. 307–8) welcomed the Berkshire atlas and expressed the hope that it would sell out quickly so that ‘the editor’s skills can be even more generously deployed in a second edition’. Perhaps this journal should modestly refrain from claiming credit, but the wish has been fulfi lled and a second edition has now appeared. Th e new edition, again published by the Berkshire Record Society and edited by Joan Dils and Margaret Yates, improves upon its predecessor in almost every way. Advances in digital technology have enabled the new edition to use several colours on the maps, and this helps enormously to reveal patterns and distributions. As before, the volume has benefi ted greatly from the design skills of the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading. Some entries are now enlivened with colour illustrations as well (for example, funerary monuments, local brickwork, a workhouse), which enhance the text, though readers could probably have been left to imagine a fl ock of sheep grazing on the Downs. -

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS Except public holidays Effective from 02 August 2020 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, School 0840 1535 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0723 - 0933 33 1433 - 1633 1743 1843 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0730 0845 0940 40 1440 1540 1640 1750 1850 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0734 0849 0944 then 44 1444 1544 1644 1754 - Great Rollright 0658 0738 0853 0948 at 48 1448 1548 1648 1758 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0747 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1457 1557 1657 1807 - South Newington - - - - times - - - - - 1903 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0626 0716 0758 0911 1006 each 06 1506 1606 1706 1816 - Bloxham Church 0632 0721 0804 0916 1011 hour 11 1511 1611 1711 1821 1908 Banbury, Queensway 0638 0727 0811 0922 1017 17 1517 1617 1717 1827 1914 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0645 0735 0825 0930 1025 25 1525 1625 1725 1835 1921 SATURDAYS 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0838 0933 33 1733 1833 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0845 0940 40 1740 1840 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0849 0944 then 44 1744 - Great Rollright 0658 0853 0948 at 48 1748 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1757 - South Newington - - - times - - 1853 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0716 0911 1006 each 06 1806 - Bloxham Church 0721 0916 1011 hour 11 1811 1858 Banbury, Queensway 0727 0922 1017 17 1817 1904 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0735 0930 1025 25 1825 1911 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Bank Holidays At Easter, Christmas and New Year special timetables will run - please check www.stagecoachbus.com or look out for seasonal publicity This timetable is valid at the time it was downloaded from our website. -

WIN a ONE NIGHT STAY at the OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always More to Discover

WIN A ONE NIGHT STAY AT THE OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always more to discover Tours & Exhibitions | Events | Afternoon Tea Birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill | World Heritage Site BUY ONE DAY, GET 12 MONTHS FREE ATerms precious and conditions apply.time, every time. Britain’sA precious time,Greatest every time.Palace. Britain’s Greatest Palace. www.blenheimpalace.com Contents 4 Oxford by the Locals Get an insight into Oxford from its locals. 8 72 Hours in the Cotswolds The perfect destination for a long weekend away. 12 The Oxfordshire Thames Path Take a walk along the Thames Path and enjoy the most striking riverside scenery in the county. 16 Film & TV Links Find out which famous films and television shows were filmed around the county. 19 Literary Links From Alice in Wonderland to Lord of the Rings, browse literary offerings and connections that Oxfordshire has created. 20 Cherwell the Impressive North See what North Oxfordshire has to offer visitors. 23 Traditions Time your visit to the county to experience at least one of these traditions! 24 Transport Train, coach, bus and airport information. 27 Food and Drink Our top picks of eateries in the county. 29 Shopping Shopping hotspots from around the county. 30 Family Fun Farm parks & wildlife, museums and family tours. 34 Country Houses and Gardens Explore the stories behind the people from country houses and gardens in Oxfordshire. 38 What’s On See what’s on in the county for 2017. 41 Accommodation, Tours Broughton Castle and Attraction Listings Welcome to Oxfordshire Connect with Experience Oxfordshire From the ancient University of Oxford to the rolling hills of the Cotswolds, there is so much rich history and culture for you to explore. -

Stapenhill House Hook Norton Oxfordshire Stapenhill House Hook Norton, Oxfordshire

Stapenhill House hook norton oxfordshire Stapenhill House Hook Norton, Oxfordshire Chipping Norton 5 miles, Banbury 9 miles, M40 (J11)10 miles, Soho Farmhouse 6 miles (all distances approximate) Regular fast train services from Banbury to Birmingham, Oxford and London Marylebone. An exceptional opportunity to update a Grade II listed village house with attached outbuildings and create a stunning family home, situated in this popular village on the edge of the Cotswolds. • Reception Hall • Sitting Room • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Three Bedrooms • Bathroom • Extensive Attic Space • Boiler Room • Two Store Rooms • Stable with Hay Store above • Open sided Barn DESCRIPTION Stapenhill House is a detached period property in need of complete modernisation, situated in an elevated south facing position on Scotland End. It has large unconverted attics and is attached to a series of interconnecting stores with barns beyond. Subject to the necessary planning regulations, these could be incorporated into the living space to create a wonderful and versatile family home with potential for either ancillary accommodation or a home office. Grade II Listed and believed to date from the 17th Century the house retains many period features including a timber ‘winder’ staircase; exposed beams; wooden panelling; oak plank doors and stone window seats. The stores and barns also retain many period features including brick or flagstone floors, a curious ‘cartwheel’ window, beams and timbers and a wooden manger. Included within this brochure is a floor plan detailing the current layout of SITUATION the property, and one can envisage a large vaulted kitchen and reception room Hook Norton is an active, sought after village situated in North within the stores to the rear, with further scope beyond. -

Clifton Past and Present

Clifton Past and Present L.E. Gardner, 1955 Clifton, as its name would imply, stands on the side of a hill – ‘tun’ or ‘ton’ being an old Saxon word denoting an enclosure. In the days before the Norman Conquest, mills were grinding corn for daily bread and Clifton Mill was no exception. Although there is no actual mention by name in the Domesday Survey, Bishop Odo is listed as holding, among other hides and meadows and ploughs, ‘Three Mills of forty one shillings and one hundred ells, in Dadintone’. (According to the Rev. Marshall, an ‘ell’ is a measure of water.) It is quite safe to assume that Clifton Mill was one of these, for the Rev. Marshall, who studied the particulars carefully, writes, ‘The admeasurement assigned for Dadintone (in the survey) comprised, as it would seem, the entire area of the parish, including the two outlying townships’. The earliest mention of the village is in 1271 when Philip Basset, Baron of Wycomb, who died in 1271, gave to the ‘Prior and Convent of St Edbury at Bicester, lands he had of the gift of Roger de Stampford in Cliftone, Heentone and Dadyngtone in Oxfordshire’. Another mention of Clifton is in 1329. On April 12th 1329, King Edward III granted a ‘Charter in behalf of Henry, Bishop of Lincoln and his successors, that they shall have free warren in all their demesne, lands of Bannebury, Cropperze, etc. etc. and Clyfton’. In 1424 the Prior and Bursar of the Convent of Burchester (Bicester) acknowledged the receipt of thirty-seven pounds eight shillings ‘for rent in Dadington, Clyfton and Hampton’. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Hook Norton, Regia Villa

Hook Norton, regia villa By JOHN BLAIR SUMMARY The ridge on which stands the iron-age hillfort Tadmarton Camp is tentatively identified as the site oj an Anglo-Saxon royal vill and the sctne oj a bailie in 913. Nearby was the original glebtland oj Hook Norlon parish church, suggtsling that the early ecclesiastical cenlre may also haUl bun on tht ridge, not in the village 2'/2 milts away. or the year 913, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records one or the abortive Viking Fcounter-attacks which punctuated the fe-conquest of the Danclaw: 1 In this year the army from NOrlhampton and Leicester rode out after Easter and broke the peace, and killed many men at Hook Norton and round about there. And then very soon after that, as the one force came home, they mel another raiding band which rode out against Luton. And then the people of the district became aware of it and fought against them and reduced them to full night ... The 12th-century Latin writer John of Worcester, who used texts of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle which are no longer extant, is slightly more hclpful:2 After Easter the pagan army from Northampton and Leicester plundered Oxrordshire, and killed many men in the royal viII Hook Norton and in many other places (in Oxenofordensi provincia praedam egerunl, et in regia villa Hokerntlunt tl in multis aliis villis quam plures occiderunl) ... It was a standard practice of pre-Conquest writers (and one which respected administrative and political realities) to locale military campaigns by reference to royal villat.'l The villa mentioned in the 913 annal has, however, disappeared from recorded memory. -

Cake and Cockhorse

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society Autumn 1973 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman and Magazine Editor: F. Willy, B.A., Raymond House, Bloxham School, Banbury Hon. Secretary: Assistant Secretary Hon. Treasurer: Miss C.G. Bloxham, B.A. and Records Series Editor: Dr. G.E. Gardam Banbury Museum J.S.W. Gibson, F.S.A. 11 Denbigh Close Marlborough Road 1 I Westgate Broughton Road Banbury OX 16 8 DF Chichester PO 19 3ET Banbury OX1 6 OBQ (Tel. Banbury 2282) (Chichester 84048) (Tel. Banbury 2841) Hon. Research Adviser: Hon. Archaeological Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. J.H. Fearon, B.Sc. Committee Members J.B. Barbour, A. Donaldson, J.F. Roberts ************** The Society was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the history of the town of Banbury and neighbouring parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The Magazine Cake & Cockhorse is issued to members three times a year. This includes illustrated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society’s activities. Publications include Old Banbury - a short popular history by E.R.C. Brinkworth (2nd edition), New Light on Banbury’s Crosses, Roman Banburyshire, Banbury’s Poor in 1850, Banbury Castle - a summary of excavations in 1972, The Building and Furnishing of St. Mary’s Church, Banbury, and Sanderson Miller of Radway and his work at Wroxton, and a pamphlet History of Banbury Cross. The Society also publishes records volumes. These have included Clockmaking in Oxfordshire, 1400-1850; South Newington Churchwardens’ Accounts 1553-1684; Banbury Marriage Register, 1558-1837 (3 parts) and Baptism and Burial Register, 1558-1723 (2 parts); A Victorian M.P. -

Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2014

Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2014 includes 2014 Museum and Galleries D of Oxfordshire Competition OR SH F IR X E O O M L U I S C MC E N U U M O S C Soldiers of Oxfodshire Museum, Woodstock www.oxfordshiremuseums.org The SOFO Museum Woodstock By a winning team Architects Structural Project Services CDM Co-ordinators Engineers Management Engineers OXFORD ARCHITECTS FULL PAGE AD museums booklet ad oct10.indd 1 29/10/10 16:04:05 Museums and Galleries of Oxfordshire 2012 Welcome to the 2012 edition of Museums or £50, there is an additional £75 Blackwell andMuseums Galleries of Oxfordshire and Galleries. You will find oftoken Oxfordshire for the most questions answered2014 detailsWelcome of to 39 the Museums 2014 edition from of everyMuseums corner and £75correctly. or £50. There is an additional £75 token for ofGalleries Oxfordshire of Oxfordshire, who are your waiting starting to welcomepoint the most questions answered correctly. Tokens you.for a journeyFrom Banbury of discovery. to Henley-upon-Thames, You will find details areAdditionally generously providedthis year by we Blackwell, thank our Broad St, andof 40 from museums Burford across to Thame,Oxfordshire explore waiting what to Oxford,advertisers and can Bloxham only be redeemed Mill, Bloxham in Blackwell. School, ourwelcome rich heritageyou, from hasBanbury to offer. to Henley-upon- I wouldHook likeNorton to thank Brewery, all our Oxfordadvertisers London whose Thames, all of which are taking part in our new generousAirport, support Smiths has of allowedBloxham us and to bring Stagecoach this Thecompetition, competition supported this yearby Oxfordshire’s has the theme famous guidewhose to you, generous and we supportvery much has hope allowed that us to Photo: K T Bruce Oxfordshirebookseller, Blackwell. -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1979. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele chairman: Alan Donaldson, 2 Church Close, Adderbury, Banbury. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Mrs N.M. Clifton Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury.: (Tel. Edge Hill 262) (Tel. Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hm. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, B.A., Dip. Archaeol. J.S. W. Gibson, F.S.A., Banbury Museum, 11 Westgate, Marlborough Road. Chichester PO19 3ET. (Tel: Banbury 2282) (Tel: Chichester 84048) Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, B.Sc., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. committee Members: Dr. E. Asser, Mr. J.B. Barbour, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs. G. W. Brinkworth, B.A., David Smith, LL.B, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover illustration is the portrait of George Fox by Chinn from The Story of Quakerism by Elizabeth B. Emmott, London (1908). CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 7 Number 9 Summer 1979 Barrie Trinder The Origins of Quakerism in Banbury 2 63 B.K. Lucas Banbury - Trees or Trade ? 270 Dorothy Grimes Dialect in the Banbury Area 2 73 r Annual Report 282 Book Reviews 283 List of Members 281 Annual Accounts 2 92 Our main articles deal with the origins of Quakerism in Banbury and with dialect in the Ranbury area. -

Stay for Mince Pies !!

DECEMBER 2015 www.barfordnews.co.uk Price 30p where sold Christmas Carol Service With a Brass Band! Sunday, 20th December 4.00pm Barford St. Michael Church Stay for mince pies !! A Happy and Peaceful Christmas To All From The News Team 1 Parish Council Notes Roadside Drains and Gullies - Mr Kelman A Meeting of the Parish Council took place at of OCC has advised that the gulley north of 7.30pm on 4 November 2015 in Barford Village the bridge will be cleared on 10 November Hall and was attended by Cllrs Hobbs, Eden, and the drains cleared and jetted soon Hanmer, Styles, Turner, Best, Campbell, District after that to allow excess water to flow Cllr Williams and Mrs Watts (Parish Clerk & freely back into the river. Responsible Financial Officer). A Cherwell Parish Liaison Meeting will take place on 11 November at Bodicote House. Minutes of the last meeting: The minutes of the Cllr Hobbs is going to attend. Parish Council Meeting on 7 October 2015 were unanimously RESOLVED as a true record of the The Parish Council website can be accessed on meeting and signed by the Chairman. www.thebarfordvillages.co.uk Dog Bin for Bloodybones Lane: a dog bin for Fix My Street – residents can report defects in Bloodybones Lane will be installed this month. the highway to Oxfordshire County Council on http://fixmystreet.oxfordshire.gov.uk OCC’s First Aid Courses: A third first aid course with St contractor pledges to fix potholes within 28 days, John Ambulance took place on 8 October. 24 hours in an emergency and within 4 hours for a severe category.