The Veteran Trees of Warwickshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Building Stone Atlas of Warwickshire

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Warwickshire First published by English Heritage May 2011 Rebranded by Historic England December 2017 Introduction The landscape in the county is clearly dictated by the Cob was suitable for small houses but when more space was underlying geology which has also had a major influence on needed it became necessary to build a wooden frame and use the choice of building stones available for use in the past. The wattle fencing daubed with mud as the infilling or ‘nogging’ to geological map shows that much of this generally low-lying make the walls. In nearly all surviving examples the wooden county is underlain by the red mudstones of the Triassic Mercia frame was built on a low plinth wall of whatever stone was Mudstone Group. This surface cover is however, broken in the available locally. In many cases this is the only indication we Nuneaton-Coventry-Warwick area by a narrow strip of ancient have of the early use of local stones. Adding the stone wall rocks forming the Nuneaton inlier (Precambrian to early served to protect the wooden structure from rising damp. The Devonian) and the wider exposure of the unconformably infilling material has often been replaced later with more overlying beds of the Warwickshire Coalfield (Upper durable brickwork or stone. Sometimes, as fashion or necessity Carboniferous to early Permian). In the south and east of the dictated, the original timber framed walls were encased in county a series of low-lying ridges are developed marking the stone or brick cladding, especially at the front of the building outcrops of the Lower and Middle Jurassic limestone/ where it was presumably a feature to be admired. -

Leek Wootton Link

FEBRUARY 2020 All Saints’ Church Parish Magazine LEEK WOOTTON LINK Leek Wootton | Guy’s Cliffe | Hill Wootton | Chesford | Goodrest | Wedgnock | North & Middle Woodloes LEEK WOOTTON LINK | FEBRUARY 2020 the GiftAid form. EDITORIAL We would reiterate that all donations Welcome to the February issue of The made are used only for publication and Link. distribution of The Link and, whilst the How time flies! After our very Church owns the magazine, it is successful annual appeal for donations supported by the Parish Council and is last year, which saw us double the the primary route for all community 2018 appeal total, it is the time, once news and information, which thanks to again, to ask for your support; you will your support continues to be free! hopefully have received a bright blue We very much hope you continue to envelope with your magazine giving full enjoy The Link and will give what information. Of course, we can’t send support you can. our eLink recipients an envelope, so Helen & Lesley Eldridge they will have received a PDF copy for The Editorial Team Cover Image: February 2019 All Saints’ Church WHO’S WHO? Vicar Readers Jim Perryman t : 850610 Audrey Rowberry t : 851498 The Vicarage, 4 Hill Wootton Road 7a The Meadows e : [email protected] Nigel Stallard (see left for contact) Church Wardens Secretary to the PCC Jonathan Kingston t : 851181 Eileen Clayton t : 855124 32 Hill Wootton Road 2 The Hamlet Nigel Stallard t : 850548 Treasurer to the PCC Reading Room Cottage Church Lane Iain Wilton t : 07771 664185 4 Croft -

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

Warwick Complex Can Accommodate Guests up to 600, with the Avon Lounges Extending the Space Available to a Further 200

www.monsoonvenuegroup.co.uk • [email protected] 0121 769 2746 ABOUT Monsoon Venue Group Monsoon Venue Group (MVG) is an exclusive venue and event management company, specialising in Asian events. We work in partnership with some of the most prestigious venues across the Midlands to help manage and deliver Asian events, from wedding receptions to private dinners. If you are looking for a high-end venue for your event, MVG has a portfolio of venues that can accommodate functions of all shapes and sizes. MVG strives to be the leading venue and event management agency bridging the gap between premium venues and the Asian events market; providing the highest levels of service and delivery to both the venues and its customer. NAEC Stoneleigh ABOUT NAEC Stoneleigh Set in 250 acres of Warwickshire countryside, Stoneleigh Park is an idyllic location for your wedding. The flexibility of our unique venue can accommodate anything from a small private pre wedding party to the main event itself. The Warwick Complex can accommodate guests up to 600, with the Avon Lounges extending the space available to a further 200. The Complex walls and ceiling are dressed in luxurious draping, giving the room a grand marquee effect. With over 800 acres of private rolling countryside views, we can also offer bespoke outdoor elements to your day. Our Smaller suite, ‘Stareton Hall’ has a capacity of 400 for a banquet reception; this suite overlooks the gardens with bandstand and is perfect for civil and religious ceremonies. The Suite has a separate entrance and foyer, located next to the Royal Pavilion and offers great a backdrop for photographs. -

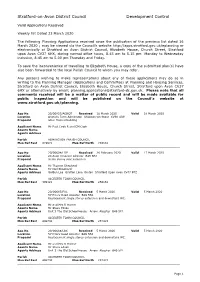

Weekly List Dated 23 March 2020

Stratford-on-Avon District Council Development Control Valid Applications Received Weekly list Dated 23 March 2020 The following Planning Applications received since the publication of the previous list dated 16 March 2020 ; may be viewed via the Council’s website http://apps.stratford.gov.uk/eplanning or electronically at Stratford on Avon District Council, Elizabeth House, Church Street, Stratford upon Avon CV37 6HX, during normal office hours, 8.45 am to 5.15 pm Monday to Wednesday inclusive, 8.45 am to 5.00 pm Thursday and Friday. To save the inconvenience of travelling to Elizabeth House, a copy of the submitted plan(s) have also been forwarded to the local Parish Council to whom you may refer. Any persons wishing to make representations about any of these applications may do so in writing to the Planning Manager (Applications and Committee) at Planning and Housing Services, Stratford on Avon District Council, Elizabeth House, Church Street, Stratford upon Avon CV37 6HX or alternatively by email; [email protected]. Please note that all comments received will be a matter of public record and will be made available for public inspection and will be published on the Council’s website at www.stratford.gov.uk/planning. _____________________________________________________________________________ App No 20/00827/AGNOT Received 18 March 2020 Valid 18 March 2020 Location Oxstalls Farm Admington Shipston-on-Stour CV36 4JW Proposal Steel framed building Applicant Name Mr Paul Cook R and EM Cook Agents Name Agents Address -

Bus Briefing 4 November 2019 PRINCETHORPE COLLEGE 2 Bus Briefing This Map Isforillustrativepurposes Only

Princethorpe College An independent school for 11-18 year olds Bus Briefing 4 November 2019 2 Briefing Bus PRINCETHORPE COLLEGE Bus Services and Routes from November 2019 S4 NUNEATON LUTTERWORTH BULKNTON S10 NORTH SHLTON PLTON KILWORTH MERIDEN COVENTRY MONKS KRB HMPTON S2 POOL MEDOW NRDEN S3 HRBOROUH CENTRL MN S5 CHURCHOVER S BRNKLOW ESENHLL SOLHULL BROWNSOER WESTWOOD BRETFORD CHURCH HETH RTONON LWFORD CLFTON BALSALL DUNSMORE WOLSTON S9 CWSTON COMMON HLLMORTON STRETTONON CRCKLE HLL DUNSMORE KENLWORTH DORRDE CHESFORD BLTON LEEK WOOTTON KLSB DUNCHURCH BOURTON SHREWLE FRNKTON BRB LPWORTH HTTON HOCKLE WESTON HETH HENLEY- CUBBNTON UNDER IN-ARDEN BRAUNSTON WETHERLE LON S12 LEMNTON SPA TCHNTON S1 WRWCK RDFORD SEMELE NPTON DENTR CLERDON MTON LEMNTON UFTON HETHCOTE SP SOUTHM SNITTERFIELD S7 STAERTON BRFORD HRBUR LESTON BSHOPS CHRLECOTE TCHNTON BDB TDDNTON STRATFORD- S6 UPON-AVON MORETON KNHTCOTE LOWER THE CROFT MORRELL BODDNTON SCHOOL WELLESBOURNE BFELD NORTHEND KNETON PILLERTON S11 MOLLNTON PRIORS TSOE S8 BANBURY This map is for illustrative purposes only. 3 Briefing Bus PRINCETHORPE COLLEGE Bus Briefing 2019-2020 This information applies to bus services with effect from Monday Our Bus Services 4 November 2019. A comprehensive private bus service brings pupils into the College There have been changes to several routes, these are outlined below. from a wide area, extending as far afield as Burbage, Nuneaton and Coventry to the north, Lutterworth and Daventry to the east, The S10 and S11 also have stops towards the start of the route Stratford-upon-Avon and Banbury to the south and Solihull and which are in grey to indicate these are currently suspended, but can Henley-in-Arden to the west. -

X16C Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X16C bus time schedule & line map X16C Kenilworth - Stratford View In Website Mode The X16C bus line Kenilworth - Stratford has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Stratford-Upon-Avon: 7:05 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X16C bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X16C bus arriving. Direction: Stratford-Upon-Avon X16C bus Time Schedule 57 stops Stratford-Upon-Avon Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:05 AM Clarendon Arms, Kenilworth 44 Castle Hill, Kenilworth Tuesday 7:05 AM Clinton Avenue, Kenilworth Wednesday 7:05 AM Herbert Bond Drive, Kenilworth Thursday 7:05 AM Cobbs Road, Kenilworth Friday 7:05 AM Clinton Lane, Kenilworth Saturday Not Operational Clinton Lane, Kenilworth Rose Croft, Kenilworth De Montfort Road, Kenilworth X16C bus Info Direction: Stratford-Upon-Avon Malthouse Lane, Kenilworth Stops: 57 Castle Hill, Kenilworth Trip Duration: 86 min Line Summary: Clarendon Arms, Kenilworth, Clinton Manor Road, Kenilworth Avenue, Kenilworth, Cobbs Road, Kenilworth, Clinton Lane, Kenilworth, Rose Croft, Kenilworth, De Tainters Hill, Kenilworth Montfort Road, Kenilworth, Malthouse Lane, Kenilworth, Manor Road, Kenilworth, Tainters Hill, Common Lane, Kenilworth Kenilworth, Common Lane, Kenilworth, Common, Kenilworth, Highland Road, Kenilworth, Knowle Hill, Common, Kenilworth Kenilworth, Mill Bank Mews, Kenilworth, Forge Road, Kenilworth, Herberts Lane, Kenilworth, Spring Lane, Common Lane, Kenilworth Kenilworth, Sports & Social Club, Kenilworth, Church, Highland -

Warwick District Council Local Plan Examination

Warwick District Council Local Plan Examination Matter 7c: Proposed housing site allocations, safeguarded land and direction for growth (Edge of Coventry) Written Statement by Warwickshire County Council A46 Link Road November 2016 1. Purpose of the Statement The purpose of this statement is to provide the Local Plan Inspector and those attending the Examination in relation to Matter 7c with details of the proposed A46 Link Road. It is not designed to form a rebuttal to any individual representations which have been made in response to the questions posed by the Inspector on Matter 7c. 2. Context Warwickshire County Council, in conjunction with Coventry City Council and Warwick District Council, is exploring ambitious proposals to ensure that the sub-region and its economy continues to benefit from a high quality transport network which supports access to jobs, improved business to business connectivity and sustainable housing and employment growth. Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council is joining with its Coventry and Warwickshire partners to explore these proposals. Coventry and Warwickshire has the fastest growing economy within the West Midlands. Infrastructure investment is needed in key corridors such as the A45 and A46 to provide the conditions for businesses to continue to invest in the area. An efficient transport network with sufficient capacity and resilience is key to maintaining and supporting future growth. The current major investment at Tollbar End near Coventry on the A45/A46 along with committed improvements at Binley (A46/A428) and Stanks near Warwick (A46/A425/A4177) demonstrate the importance of this corridor to the sub-regional economy. There is also an aspiration over time to see the A46 become an ‘Expressway’ between the M6/M69, M40 and M5. -

The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond

T H A M E S V A L L E Y AARCHAEOLOGICALRCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment by Tim Dawson Site Code PLR12/80 (TQ 1793 7520) The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment for Renworth Homes (Southern) Ltd In support of a detailed planning application and Conservation Area Consent application for the erection of three new townhouses, with car parking and conversion of existing school building for six residential units with car parking by Tim Dawson Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code PLR 12/80 AUGUST 2012 Summary Site name: The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Grid reference: TQ 17925 75200 Site activity: Desk-based heritage assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Tim Dawson Site code: PLR 12/80 Area of site: c.0.12ha Summary of results: The Old School lies in an area of high archaeological potential with finds and features dating from the Palaeolithic period onwards being discovered nearby. Richmond itself was an important centre with its royal palace dating from the medieval period. While construction of the school in 1870 is likely to have disturbed at least the most shallow archaeological deposits, the area under the playground is less likely to have been truncated allowing for the preservation of archaeologically sensitive layers. It is anticipated that it will be necessary to provide further information about the archaeological potential of the site from field observations, in order to draw up a scheme to mitigate the impact of the proposed residential development on any below-ground archaeological deposits if necessary. -

Warwickshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects West Midlands WARWICKSHIRE North Warwickshire 3/1548 (E.44.L006) SP 32359706 CV9 1RS 30 THE SPINNEY, MANCETTER Mancetter, 30 the Spinney Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 3pp, figs Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services The site lies in an area where well preserved remains of Watling Street Roman Road were exposed in the 1970's. No Roman finds were noted during the recent developments and imported material suggested that the original top soil and any archaeological layers were previously removed. [Au(abr)] SMR primary record number:386, 420 3/1549 (E.44.L003) SP 32769473 CV10 0TG HARTSHILL, LAND ADJACENT TO 49 GRANGE ROAD Hartshill, Land Adjacent to 49 Grange Road Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 3pp, figs, Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services No finds or features of archaeological significance were recorded. [Au(abr)] 3/1550 (E.44.L042) SP 17609820 B78 2AS MIDDLETON, HOPWOOD, CHURCH LANE Middleton, Hopwood, Church Lane Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 4pp, figs Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services The cottage itself was brick built, with three bays and appeared to date from the late 18th century or early 19th century. A number of timber beams withiin the house were re-used and may be from an earlier cottage on the same site. The watching brief revealed a former brick wall and fragments of 17th/18th century pottery. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: PM 3/1551 (E.44.L007) SP 32009650 CV9 1NL THE BARN, QUARRY LANE, MANCETTER Mancetter, the Barn, Quarry Lane Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 2pp, figs Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services The excavations uncovered hand made roof tile fragments and fleck of charcoal in the natural soil. -

Site Allocations Plan Draft Pre-Submission June 2014 North

Site Allocations Plan Draft Pre-submission June 2014 North Warwickshire Local Plan Draft Pre-submission Site Allocations Plan June 2014 CONTENTS: 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Site Allocation Plan 3 Evidence Base 4 2. EMPLOYMENT LAND 5 Existing Employment Sites 6 New Employment Land 6 - Dordon Sites 8 - Atherstone Sites 10 Renewable Energy Proposal – Power station B Site, 11 Hams Hall Employment Site Allocations and Proposals Maps 12 3 TRANSPORT PROPOSALS 16 - New Station Sites, Kingsbury and Arley 16 - Safeguarded Land North of Dunns Lane 17 - New Access Road Investigation 17 HS2 Safeguarded Route 19 4. RETAIL 20 Town Centre Boundaries & Core Shopping frontages 20 Neighbourhood Centres 24 5. HOUSING 26 Housing Site Allocation for Settlements 26 Housing Numbers from Core Strategy 28 Settlement Site Allocations 30 - Atherstone & Mancetter Sites 31 - Polesworth & Dordon Sites 34 - Coleshill Sites 38 - Baddesley Ensor & Grendon Sites 40 - Hartshill & Ansley Common Sites 45 - Old & New Arley Sites 49 - Kingsbury Sites 51 - Water Orton Sites 53 - Ansley Sites 55 - Austrey Sites 57 - Curdworth Sites 60 - Fillongley Sites 62 - Hurley Sites 64 - Newton Regis Sites 66 - Piccadilly Sites 68 - Shuttington Sites 70 - Shustoke Sites 71 - Warton Sites 72 - Whitacre Heath Sites 74 - Wood End Sites 76 1 Draft Pre-submission Site Allocations Plan June 2014 Housing for Older People 78 Affordable Housing Sites 78 Other Villages and Hamlets 79 6. Green Belt Settlements 80 Green Belt Infill boundary Villages 81 7. Open Space 84 New Open Space/Recreation Proposals 85 - Dordon 84 - Atherstone 86 Safeguarding former rail routes/Links 86 Local Nature Reserves 91 8. Proposals Map and Site Allocations 94 Appendix A – Existing Employment Sites - Appendix B – HS2 Y Route Proposed - Appendix C – All Sites with Planning Consent as at - March 2014 Appendix D – Green Belt Infill Boundary Maps - Appendix E – Open Space Allocations - Appendix F – Infrastructure Delivery Plan - Borough wide and settlement needs identified. -

Plate Whether Miller Was Responsible for The

although it is not mentioned by Heely. (Plate ) Whether Miller was responsible for the transformation of the house, by the addition of towers, pointed windows and castellations, so that it appeared "like a castlen is not known, but it is possible that this was the work of William Baker, an architect and surveyor who worked largely in Staffordshire and Shropshire. 9 Country Life, IX (1901) p. 336. W. Shenstone, Letters, ed. M. Williams (London 1939) p. 261. The building he describes stands at the upper end of the lawn at the back of the house, which is exactly the position of the museum. (R. Pococke, Travels through England, (Camden Soc. 1889) 11, p. 23q.) J. Heely, Letters on the Beauties of Hagley, Envil and the Leasowes, (1777) 11, p. 82. The roof has now gone and the ceiling collapsed, but much of the internal -plasterwork and the marble fireplace remains. Pococke, locÈcit Heely, op.cit., p. 76. John Ivory Talbot to Miller: Lacock, Sept. ? 1754: CR 125~/@1. Heely, op.cit., pp. 25-93. I have used Heely16 names for the buildings. The Cottage, of which practically nothing remains is known as the Hermitage;- the Shepherd's- Lodge as Sheepwalk House. 9. J. Britton, Beauties of England and Wales, (London 1813) Vol.13, pt.ii, p.853. Pococke, 1oc.cit. Colvin, Dictionary, p. 53. 19. INGESTRE, STAFFORDSHIRE. At the request of George Lyttelton, Sanderson Miller sent John, Viscount Chetwynd, a design for a gothic tower for his estate at Ingestre. In June 1749 Lyttelton commented that he had engaged Miller "in a great deal of business: first for myself, then for 1 Lord Chetwynd and now for my Lord Chancellorn.