A Case Study of Taman Melawati Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

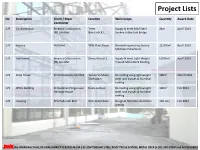

Project Lists

Project Lists No Description Client / Main Location Work Scope Quantity Award Date Contractor 175 Condominium Binastra Construction Treez Supply & erect Mild Steel 24m April’ 2013 (M) Sdn Bhd Bukit Jalil,K.L. Sunken Lobby Link Bridge 174 Factory YKGI Bhd YKGI Plant,Kapar. Dismantling existing factory 12,000m2 April’ 2013 Mild Steel Structures 173 Apartment Binastra Construction Danau Kota,K.L. Supply & erect Light Weight 6,000m2 April’ 2013 (M) Sdn Bhd Truss & Metal Deck Roofing 172 Shop House Penril Datability Sdn Bhd Taman Sri Muda, Re-roofing using light weight 280m2 March’2013 Shah Alam steel roof trusses & fix metal roofing 171 Office Building Perbadanan Pengurusan Kuala Lumpur. Re-roofing using light weight 300m2 Feb’2013 Heritage House steel roof trusses & fix metal roofing 170 Housing KPG Padu Sdn Bhd Nilai,N.Sembilan Design & fabricate steel drain 150 sets Feb’2013 grating DNK, We-MANUFACTURE,DESIGN,FABRICATE&INSTALL M.S & LIGHT WEIGHT STEEL ROOF TRUSS SYSTEM, METAL DECK & CEILLING STRIP and ACCESSORIES Project Lists No Description Client / Main Location Work Scope Quantity Award Date Contractor 169 Steel Support Frame for Archi-Foam Sdn Bhd Mont Kiara Kuala Design & build steel frame 3 mT Dec’2012 Condominium Lumpur support for light weight foam concrete 168 Ware House extension Kara Marketing (M) Sdn Puchong Selangor Design & build mild steel 30 mT Nov’2012 steel structure Bhd structure for warehouse extension 167 Shop Houses 24 Units Hong & Hong Groups Kota Kemuning, Design & build light weight steel 3,350 m2 Oct’2012 Sdn Bhd Shah Alam roof trusses & fax metal deck roofing 166 Workshop Muner Hanafiah Taman Tun Dr. -

Panel Windscreen Repairers

PANEL WINDSCREEN REPAIRERS PENANG TOWN WORKSHOP NAME CONTACT NO ADDRESS BUKIT MERTAJAM KEDAI MEMASANG CERMIN KERETA HOCK LEE HENG 04-310 7518 NO.4961, JALAN BAGAN AJAM, 13000 BUKIT MERTAJAM, PULAU (JALAN BAGAN AJAM, BUKIT MERTAJAM) 04-324 4518 PINANG BUKIT MERTAJAM KEDAI MEMASANG CERMIN KERETA HOCK LEE HENG 04-551 7518 NO.3314, JALAN KULIM, CHEROK TOKUN, 14000 BUKIT MERTAJAM, (JALAN KULIM, BUKIT MERTAJAM) PULAU PINANG BUKIT MERTAJAM KEDAI MEMASANG CERMIN KERETA HOCK LEE HENG 04-530 7852 NO.5954, JALAN MEGAT HARUN, 14000 BUKIT MERTAJAM, PULAU (JALAN MEGAT HARUN,BUKIT MERTAJAM) 04- 538 9716 PINANG BUTTERWORTH DR CERMIN SDN BHD (BUTTERWORTH) 016-470 3938 6004, JALAN HENG CHOON THIAN, 12100 BUTTERWORTH, PULAU 04-333 4310 PINANG GEORGE TOWN FEDERAL MOTOR (GEORGE TOWN) 04-283 1206 77 & 77A, LORONG KULIT, 10460 GEORGETOWN, PULAU PINANG GEORGE TOWN YAN KEE AUTO GLASS (GEORGE TOWN) 04-281 3378 89-I, JALAN P.RAMLEE, 10460 GEORGETOWN, PULAU PINANG SEBERANG PERAI SPEEDY AUTO GLASS SPECIALITS SDN BHD (SEBERANG 04-399 0979 NO.14, JALAN PERAI JAYA, BANDAR PERAI JAYA, 13700 SEBERANG PERAI) PERAI, PULAU PINANG KEDAH TOWN WORKSHOP NAME CONTACT NO ADDRESS ALOR SETAR DR CERMIN SDN BHD (ALOR STAR II) 012-280 9925 6B JALAN LENCONG BARAT, TAMAN DAHLIA III, 05400 ALOR SETAR, KEDAH ALOR SETAR DR CERMIN SDN BHD (ALOR STAR) 016-488 0336 NO. 5 TAMAN MURNI, SEBERANG JALAN PUTRA, 05150 ALOR STAR, KEDAH SUNGAI PETANI DR CERMIN SDN BHD (SUNGAI PETANI) 016-416 2990 NO.212, JALAN LEGENDA 8, LEGENDA HEIGHTS, 08000 SUNGAI PETANI, KEDAH SUNGAI PETANI DR CERMIN SDN BHD (SERI TEMIN) 012-498 7991 NO. -

Top Holders Snapshot - Ungrouped Composition : ES1, ORD

CIRCLE INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED ORDINARY FULLY PAID SHARES (TOTAL) As of 18 Jun 2019 Top Holders Snapshot - Ungrouped Composition : ES1, ORD Rank Name Address Units % of Units 2A-2-20 DESA IMPIANA, JALAN PRIMA 1. TAN HO UTAMA 2, PUCHONG PRIMA 47100, 74,184,450 41.21 PUCHONG SELANGOR, MALAYSIA 160 JALAN TIMAH 2, THE MINES RESORT 2. TEE XUN HAO CITY, SERI KEMBANGAN, 43300 20,788,863 11.55 SELANGOR, MALAYSIA NO 46 JALAN PERAK 7/1F, SEKSYEN 7, 3. YIP CHIN HWEE 40000 SHAH ALAM, SELANGOR 12,654,292 7.03 MALAYSIA NO 145 JALAN H12, TAMAN MELAWATI, 4. YAP CHEE LIM 6,310,905 3.51 53100-WP KUALA LUMPUR, MALAYSIA ANYUAN ROAD 777 NONG 6-2503, 5. MR KEN YIP NG JINGAN DISTRICT SHANGHAI, 200042, 6,032,483 3.35 CHINA 2A-2-20 DESA IMPIANA, JALAN PRIMA 6. PANG NYUK LING UTAMA 2, PUCHONG PRIMA 47100, 3,712,297 2.06 PUCHONG SELANGOR, MALAYSIA 12-15-3 ROBSON CONDO, PERSIARAN 7. CHONG KUR SEN SYED PUTRA 2, 50460 KUALA LUMPUR, 3,300,774 1.83 MALAYSIA 37 JALAN USJ 11/2, 47620 SUBANG JAYA, 8. CHONG KAI CHIN 2,329,807 1.29 SELANGOR MALAYSIA A-9-1 MEDAN PUTRA CONDO, JLN 9. CHONG KIN TUCK MEDAN PUTRA 2 BDR, MENJALARA 2,151,605 1.20 52200, KUALA LUMPUR MALAYSIA 01-06-15 KUCHAI BREM PARK, JLN 10. WONG CHEN YU SELESA 2, TAMAN GEMBIRA, KUALA 1,719,810 0.96 LUMPUR 58200, MALAYSIA 8 JALAN TBK 1/3A, TAMAN BUKIT 11. GOH TOH HENG KINRARA, 47180 PUCHONG, SELANGOR 1,577,726 0.88 MALAYSIA Page 1 of 2 Rank Name Address Units % of Units C-6-10 BERKELEY PARK, SRI PUTRAMAS 12. -

The Comparison of Environmental Conditions Between Hotspot and Non Hotspot Areas of Dengue Outbreak in Selangor, Malaysia

International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research Vol.3; Issue: 4; Oct.-Dec. 2018 Website: www.ijshr.com Original Research Article ISSN: 2455-7587 The Comparison of Environmental Conditions between Hotspot and Non Hotspot Areas of Dengue Outbreak in Selangor, Malaysia Nurul Akmar Ghani1, Shamarina Shohaimi1, Alvin Kah Wei Hee1, Chee Hui Yee2, Oguntade Emmanuel3, Lamidi Sarumoh Alaba Ajibola4 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia 2Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia 3Institute for Mathematical Research, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia 4Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Corresponding Author: Nurul Akmar Ghani ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Dengue affects 40% of worldwide Dengue fever is one of the most killer vector- population and becomes the most killer borne disease in the world and Malaysia has vector-borne disease in the world. [1] In recorded increases in number of dengue cases Asia, high dengue incidences were reported, and deaths since 2012. For several years, and in Southeast Asia, the tropical and Selangor state recorded the highest number of cases and deaths in Malaysia due to dengue warmer part of Asia, mortality and morbidity rate of dengue were continuously fever. Most of the dengue infections occur [2] among people who live in hotspot areas of reported at higher incidence annually. dengue, and less likely to occur among people Two most well-known mosquitoes that who live in non-hotspot areas. This study aims spread dengue virus are Aedes aegypti and to compare the difference of environmental Aedes albopictus. -

Sime Darby Property Profile

SIME DARBY PROPERTY BERHAD Citi Asia Pacific Property Conference 2018 Investor Presentation 28 – 29 June 2018 2 Presentation Outline 1 Sime Darby Property Profile Key Growth Areas and Recent 2 Developments 3 Growth Strategies 4 Financial and Operational Highlights 5 Megatrends & Market Outlook 6 Appendices 1 Sime Darby Property 3 4 Shareholding Structure RM1.16 Share Price 55.6% Share Price Movement (RM) 1.78 As at 22 June’18 1.16 1.11 Foreign Shareholdings 14.8% 10.0% RM7.9bn 4.7% Market Capitalisation Other Domestic Shareholdings 14.9% 6,800,839 Number of Ordinary and the public Shares (000’) Source: Tricor 5 The Largest Property Developer in Malaysia In terms of land bank size RM1.7bn RM637mn RM593mn 1,602 9MFY18 Revenue 9MFY18 PBIT 9MFY18 PATAMI Employees UNITED KINGDOM Property Development THAILAND Active townships, integrated and KEDAH 23 niche developments Helensvale, Acres of remaining Queensland developable land bank to be GEORGETOWN, 65 acres 20,695 developed over 10 -25 years PENANG PENINSULA MALAYSIA AUSTRALIA Estimated Remaining Gross RM96bn Development Value (GDV) Average trading discount to 45% Realised Net Asset Value (RNAV) SELANGOR 3,291 acres Property Investment 3,187 acres Sq. ft. of net commercial 2,826 acres NEGERI space in Malaysia and SEMBILAN 1.4mn Singapore 1,462 acres JOHOR Hospitality & Leisure BANDAR UNIVERSITI PAGOH Assets across 4 countries 3,297 acres Key Developments including 2 golf courses (36-hole 6 & 18-hole respectively) and a North-South Expressway Singapore convention center 6 Sustainable Growth With remaining developable land over 10 to 25 years By Remaining By Remaining Gross Developable Land Development Value (GDV) 7.6 1,461 21.0 (9%) (12%) 3,451 (26%) (28%) O 334 N (3%) G 12,265 28.2 RM81.5 O (35%) 2,826 5.5 I (23%) acres 871 billion (7%) N (7%) G 5.3 (6%) 3,322 13.9 (27%) (17%) Legend: 2,036 F (24%) U 3,092 T 8,430 (37%) RM14.4 U acres billion R for Guthrie Corridor only E 3,302 (39%) Notes: 1. -

The Association of Banks in Malaysia List of Participating Branches With

The Association of Banks in Malaysia List of participating branches with extended operation hours for debit card replacement to PIN-enabled debit card (by state in alphabetical order) Bank: Malayan Banking Berhad State Branch / Centre Branch address Johor Batu Pahat 32-4, Jalan Rahmat, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor Kluang 30-34, Jalan Dato Haji Hassan, 86000 Kluang, Johor Jalan Genuang, No 62J & 62K, Jln Genuang, Segamat Branch 85000 Segamat, Johor Muar 104, Jalan Abdullah, 80400 Muar, Johor Kulai No. 193, 194, 195 & 196, Jalan Kenanga 29/4, Indahpura, 81000 Kulaijaya, Johor Kota Tinggi 18 & 19, Jalan Niaga Satu, Pusat Perdagangan, 81900 Kota Tinggi, Johor Johor Bahru Main 106-108, Jalan Wong Ah Fook, 80000 Johor Bahru, Johor Taman Daya 18 & 20, Jalan Sagu 8, Taman Daya, 81100 Johor Bahru, Johor Bukit Pasir No 31 & 32, Jln Mengkudu, Taman Abdul Rahman Jaafar, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor Rengit Lot 10, Jalan Muhibbah, 83100 Rengit, Johor Pagoh S/C No. 14-3 & 14-4, Pagoh Main Road, Pekan Pagoh, 84600 Muar, Johor Bandar Baru Permas G-01, 01-01 & 02-01, Block A Permas Mall, Jaya No 3 Jalan Permas Utara, Bandar Baru Permas Jaya, 81750 Masai, Johor Taman Universiti 1, Kebudayaan 4, Taman Universiti, 81300 Skudai, Johor Skudai 18-20, Jalan Perwira 17, Taman Ungku Tun Aminah, 81300 Skudai, Johor Taman Johor Jaya 85-87, Jalan Dedap 6, Taman Johor Jaya, 81100 Johor Bahru, Johor Taman Nusa Bistari 15, Jalan Bestari 1/5, Taman Nusa Bestari, 81300 Skudai, Johor Mersing 22-4, Jalan Ismail, 86800 Mersing, Johor Taman Perling No. 17 & 19, Jalan Persisiran Perling, Taman Perling, 81200 Johor Bahru, Johor Tampoi 59, Jalan Sri Bahagia Lima, Taman Seri Bahagia, Tampoi, 81250 Johor Bahru, Johor Page 1 of 9 AEON Bukit Indah Lot G02, AEON Bukit Indah Shopping Centre, S/C No 8, Jalan Indah 15/2, Taman Bukit Indah, 81200 Johor Bahru Masai No. -

Capitamalls Asia Limited 凱德商用產業有限公司*

The Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited, Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CAPITAMALLS ASIA LIMITED * 凱德商用產業有限公司 (Singapore Company Registration Number: 200413169H) (Incorporated in the Republic of Singapore with limited liability) (Hong Kong Stock Code: 6813) (Singapore Stock Code: JS8) OVERSEAS REGULATORY ANNOUNCEMENT This overseas regulatory announcement is issued pursuant to Rule 13.09(2) of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. Please refer to the next page for the document which has been published by CapitaMalls Asia Limited (the “Company”) on the website of the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited on 9 May 2012. BY ORDER OF THE BOARD CapitaMalls Asia Limited Kannan Malini Company Secretary Hong Kong, 9 May 2012 As at the date of this announcement, the board of directors of the Company comprises Mr Liew Mun Leong (Chairman and non-executive director), Mr Lim Beng Chee as the executive director; Ms Chua Kheng Yeng Jennie and Mr Lim Tse Ghow Olivier as non-executive directors; and Mr Sunil Tissa Amarasuriya, Tan Sri Amirsham A Aziz, Dr Loo Choon Yong, Mrs Arfat Pannir Selvam, Professor Tan Kong Yam and Mr Yap Chee Keong as independent non-executive directors. * For identification purposes only ACQUISITIONS AND DISPOSALS Page 1 of 1 ACQUISITIONS AND DISPOSALS :: CHANGES IN COMPANY'S INTEREST :: CAPITAMALLS ASIA AND SIME DARBY PROPERTY TO JOINTLY DEVELOP SHOPPING MALL IN THE KLANG VALLEY Like 0 0 * Asterisks denote mandatory information Name of Announcer * CAPITAMALLS ASIA LIMITED Company Registration No. -

Prospect and Sustainability of Property Development on Highland and Steep Slope Areas in Selangor-Malaysia: Re- Examining of Regulations and Guidelines

RICS COBRA 2012 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________10-13 September 2012, Las Vegas, Nevada USA ISBN: 978-1-84219-840-7 . Prospect and Sustainability of Property Development on Highland and Steep Slope Areas in Selangor-Malaysia: Re- Examining of Regulations and Guidelines Anuar Alias1 & Khairul Nizam Othman1 1Centre for Building, Construction and Urban Studies (CeBUS) Faculty of Built Environment University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: Governing property development has always requires a holistic approach in decision making. The legislations for property development that are in placed still could not ensure the sustainability of development pertinently on highland and steep slope areas. These areas need more detail consideration and approaches specifically in the development process, implementation as well as the monitoring aspect. In lieu of that, the current planning, development guidelines and regulations have been evaluated as to examine the effectiveness of the current development mechanism in ensuring sustainable highland and steep slope development. Evidences from the case study have shown that the weaknesses lie in the decision making process, implementation and enforcement aspect of the property development process which have high influence in the property development growth and values. Besides, the study also revealed that property legislation setting should provide the implementation mechanism. Recommendations to ensure the prospect and sustainability of high land and steep slope development are emphasis on the needs in continuation of legislations and implementation procedures, monitoring actions as well as the necessity for the development players to collaborate and understand the important of sustainable development. Keywords: Highland, Legislations, Property Development, Steep Slope Areas, Sustainable. -

BP4 : Kawasan Pemeliharaan

PELANPELAN SUBJEKSUBJEK BLOKBLOK PERANCANGANPERANCANGAN 44 PELAN SUBJEK ALAM SEKITAR PELAN SUBJEK PERUMAHAN PELAN SUBJEK RANGKAIAN JALAN DAN PERSIMPANGAN WÜtyWÜtyWÜty RANRANCANGAN CAN GAN TEMTEMPATAN PATAN MAJLISMAJLIS PERBANPERBAN D D ARAN ARAN AMPANAMPAN G G JAYAJAYA 20202020 RAJAH 8.13 PELAN SUBJEK ALAM SEKITAR KAWASANKAWASAN PENTADBIRANPENTADBIRAN UTARAUTARA BP 4 : KAWASAN PEMELIHARAAN MAJLISMAJLIS PERBANDARANPERBANDARAN SELAYANGSELAYANG SKALASKALA :: 00 2,0002,000 4,0004,000 PETUNJUKPETUNJUK :: PERTANIANPERTANIAN METERMETER 1.1. PertanianPertanian KSAS TAHAP I : ZON SUMBER BEKALAN AIR BERSIH Empangan Klang Gates BADANBADAN AIRAIR Jasad air ini perlu dipelihara sepenuhnya dan merupakan 1.1. BadanBadan AirAir kawasan keselamatan. HUTANHUTAN -Membekalkan air ke kawasan Lembah Klang dan juga HutanHutan SimpanSimpan KSAS TAHAP I: ZON PERLINDUNGAN 1.1. HutanHutan berfungsi sebagai kawalan banjir oleh Jabatan Pengairan HuluHulu GombakGombak WARISAN, HUTAN SIMPAN , SUMBER AIR dan Saliran. BERSIH & TANAH TINGGI Taman Negeri Selangor SEMPADANSEMPADAN NEGERINEGERI (Hutan Simpan Ulu Gombak) SEMPADANSEMPADAN DAERAHDAERAH -Memerlukan pelan pengurusan SEMPADANSEMPADAN PENTADBIRANPENTADBIRAN TAKAT PENGAMBILAN AIR - Kawasan perlindungan ini bertindih dengan SEMPADANSEMPADAN BLOKBLOK PERANCANGANPERANCANGAN Sg. Pusu kawasan hutan simpan sedia ada. SEMPADANSEMPADAN BLOKBLOK PERANCANGANPERANCANGAN KECILKECIL BPBP 44 KAWASANKAWASAN PEMELIHARAANPEMELIHARAAN SEMPADANSEMPADAN BLOKBLOK PERANCANGANPERANCANGAN KECILKECIL - Perlu mewartakan rizab sungai EMPANGANEMPANGAN -

Download File

Cooperation Agency Japan International Japan International Cooperation Agency SeDAR Malaysia -Japan About this Publication: This publication was developed by a group of individuals from the International Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) at Tohoku University, Japan; Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) Kuala Lumpur and Johor Bahru; and the Selangor Disaster Management Unit (SDMU), Selangor State Government, Malaysia with support from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). The disaster risk identification and analysis case studies were developed by members of the academia from the above-mentioned universities. This publication is not the official voice of any organization and countries. The analysis presented in this publication is of the authors of each case study. Team members: Dr. Takako Izumi (IRIDeS, Tohoku University), Dr. Shohei Matsuura (JICA Expert), Mr. Ahmad Fairuz Mohd Yusof (Selangor Disaster Management Unit), Dr. Khamarrul Azahari Razak (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Kuala Lumpur), Dr. Shuji Moriguchi (IRIDeS, Tohoku University), Dr. Shuichi Kure (Toyama Prefectural University), Ir. Dr. Mohamad Hidayat Jamal (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia), Dr. Faizah Che Ros (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Kuala Lumpur), Ms. Eriko Motoyama (KL IRIDeS Office), and Mr. Luqman Md Supar (KL IRIDeS Office). How to refer this publication: Please refer to this publication as follows: Izumi, T., Matsuura, S., Mohd Yusof, A.F., Razak, K.A., Moriguchi, S., Kure, S., Jamal, M.H., Motoyama, E., Supar, L.M. Disaster Risk Report by IRIDeS, Japan; Universiti Teknologi Malaysia; Selangor Disaster Management Unit, Selangor State Government, Malaysia, 108 pages. August 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License www.jppsedar.net.my i Acknowledgement of Contributors The Project Team wishes to thank the contributors to this report, without whose cooperation and spirit of teamwork the publication would not have been possible. -

MALAYSIA PROPERTY EXPO 2019 MAPEX AMPANG / SELAYANG 1-3 November 2019 | Melawati Mall | 10.00 Am – 10.00Pm

MAPEX Ampang / Selayang HOME OWNERSHIP CAMPAIGN – MALAYSIA PROPERTY EXPO 2019 MAPEX AMPANG / SELAYANG 1-3 November 2019 | Melawati Mall | 10.00 am – 10.00pm FACT SHEET 1) Introduction: Home Ownership Campaign (HOC) 2019 is an initiative announced by the Minister of Finance, YB Mr Lim Guan Eng, during the tabling of Budget 2019 last November whereby Malaysian house-buyers will be exempted from stamp duties for purchase of residential units made between January to December 2019. HOC is open to all homebuyers to encourage property ownership and stimulate the Homeownership Campaign. Malaysia Property Exposition (MAPEX) is well established as the premier and largest convenient one-stop centre in bringing together a wide range of innovative property developments from under construction to completed properties and offers attractive financial packages for potential purchasers and investors. MAPEX Ampang / Selayang – is the exclusive edition of MAPEX in Selangor and in conjunction with the ongoing campaign as to support and spread awareness about the campaign. Developers will also offer attractive discounts and packages for house purchases made during the period. 2) Name of Event & Organiser o ‘MAPEX’ (an acronym for Malaysia Property Expo); MAPEX Ampang / Selayang organized by REHDA Selangor. 3) Event Information o Date: 1-3 November 2019 (Friday - Sunday) o Venue: Ground Floor, Melawati Mall o Exhibition Hours: 10:00 am - 10:00 pm *Free admission to the public 4) Exhibitors o No of Exhibitors confirmed participating (as of 30 October 2019): o 5 Developers . S P Setia Berhad . Platinum Victory Holdings Sdn. Bhd. OSK Property . Mitraland Group . Symphony Life Berhad o 1 Financial Instituition . -

Kuala Lumpur Yes / No Selangor Yes / No Putrajaya Yes / No Sri Petaling

Kuala Lumpur Yes / No Selangor Yes / No Putrajaya Yes / No Sri Petaling Yes Alam Impian No Putrajaya No Ampang Hilir Yes Aman Perdana No Bandar Damai Perdana Yes Ambang Botanic No Bandar Menjalara Yes Ampang Yes Bandar Tasik Selatan Yes Ara Damansara Yes Bangsar Yes Balakong No Bangsar South Yes Bandar Botanic No Batu Caves Yes Bandar Bukit Raja No Brickfields Yes Bandar Bukit Tinggi No Bukit Bintang Yes Bandar Kinrara Yes Bukit Jalil Yes Bandar Puteri Klang No Bukit Ledang Yes Bandar Puteri Puchong Yes Bukit Persekutuan Yes Bandar Saujana Putra No Bukit Tunku Yes Bandar Sungai Long No Cheras Yes Bandar Sunway Yes City Centre Yes Bandar Utama Yes Country Heights Yes Bangi No Country Heights Damansara Yes Banting No Damansara Yes Batang Berjuntai No Damansara Heights Yes Batang Kali No Desa Pandan Yes Batu Arang No Desa Park City Yes Batu Caves Yes Desa Petaling Yes Beranang No Gombak Yes Bukit Antarabangsa No Jalan Ipoh Yes Bukit Jelutong No Jalan Kuching Yes Bukit Rahman Putra No Jalan Sultan Ismail Yes Bukit Rotan No Jinjang Yes Bukit Subang No Kenny Hills Yes Cheras Yes Kepong Yes Contry Heights No Keramat Yes Cyberjaya No KL City Yes Damansara Damai No KL Sentral Yes Damansara Intan Yes KLCC Yes Damansara Jaya Yes Kuchai Lama Yes Damansara Kim Yes Mid Valley City Yes Damansara Perdana Yes Mont Kiara Yes Damansara Utama Yes Old Klang Road Yes Denai Alam No OUG Yes Dengkil No Pandan Indah Yes Glenmarie No Pandan Jaya Yes Gombak No Pandan Perdana Yes Hulu Langat No Pantai Yes Hulu Selangor No Pekan Batu Yes Jenjarom No Salak Selatan