Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 02:55:52PM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number 7 March 1963 Volume 1

/ • A**t*t*h NUMBER 7 MARCH 1963 VOLUME 1 PHILATELIC ASPECTS OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES - Bob Bruce - The Pan American Games are one of six specific competitions to which the Inter national Olympic Committee has given Its definite sanction. These Include the Far East Games (discontinued In 1930) and the Central American and Caribbean Games, the Bolivarlan Games, the Pan American Games, the Mediterranean Games, and the Asian Games, all of which are going strongly In their Individual cycles despite scattered political handicaps In a few cases. The plan for the Pan American Games is for competition every four years in the year directly preceding the Olympic Games. Entry Is limited to the countries of North, Central, and South America. The first Pan American Games were held In Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1951. Then followed Games In Mexico City in 1955 and in Chi cago in 1959. The Fourth Pan American Games will be held from April 20th to May 5th of this year in Sao Paulo, Brazil. With these Games leas than two months away, plans for participation by the ath letes of the United States are in the final stage of execution. Yet the very timing of the Games presents some Intriguing problems. Since the Games are being staged In what i3 normally an "off-season" for this country, United States Olympic Committee activities relative to team selection and pre-competltion conditioning are forced into a race against time. In addition, it is likely that the personnel of this Pan American team will exceed In number that on an average Olympic team at the very time when regular fund raising programs are Just beginning to get underway. -

WORLD RANKING of COUNTRIES in ELITE SPORT by Nadim Nassif

RIVISTA DI ISSN 1825-6678 DIRITTO ED ECONOMIA DELLO SPORT Vol. XIV, Fasc. 2, 2018 WORLD RANKING OF COUNTRIES IN ELITE SPORT by Nadim Nassif* ABSTRACT: Researchers, media, and sports leaders use the Olympic medal table at the end of each edition of the Winter or Summer Games as a benchmark for measuring the success of countries in elite sport. This ranking, however, has several limitations, such as: i) the absolute superiority of a gold medal over any number of silver and bronze creates the false inference that a country with one outstanding athlete capable of winning a gold medal is superior to another in events where several athletes finish second and third; ii) by not considering the number of countries participating in each event, the medal table does not consider the competition level of each sport; iii) only 87 of the 206 National Olympic Committees won medals when the 2016 Summer and 2018 Winter Olympic medal tables are combined. This statistical feature prevents an adequate comparative analysis of the success of countries in elite sport, considering that 58% of participants are absent. To overcome this lack, Nassif (2017) proposed a methodology with the following characteristics: a) a computation model that gives each country its share of points in at least one sport and, consequently, its world ranking based on the total number of points that particular country has obtained in all the sports in which it participates; b) the introduction of coefficients of universality and media popularity for each sport. Apart from accurately assessing the performance of all countries in international competitions, this study in the future aims to undertake in-depth studies of the factors that determine the success or failure of nations in elite sport. -

Rakshan RADPOUR

Rakshan RADPOOR (IRI) FEI ID: 10049997 FEI Official Status: Function Discipline Status Begin Date Course Designer Jumping 4 01/07/2013 Course Designer Jumping 3 05/01/2009 Judge Jumping 3 05/01/2009 Steward Jumping 2 05/01/2009 Technical delegate Jumping 4 01/07/2013 Technical delegate Jumping 3 01/01/2009 Additional Role Discipline Begin Date NF Contact Judge Jumping 05/01/2009 IRI Course Director - Course Designer Jumping 01/01/2009 IRI NF General Steward Jumping 05/01/2009 IRI FEI Nominations Committee Member 2007-2013 Asian Equestrian Federation Jumping Committee Chairman 2003-2011 FEI Official Experience: Officiated as Judge, Technical Delegate and Course Designer in 39 countries over the last 24 years: 1994 Assistant CD, CSIO, Hickstead, England 1994 Assistant CD, CCI, Badminton, England 1994 Assistant CD, Royal Windsor horse show, England 1994 Judge, CSA, Inner Mongolia, China 1995 Assistant CD, CSI, Minsk,Belarus 1996 Assistant CD, CSI ,Neumarkt, Germany 1996 President Ground Jury, National Championship, Russia 1996 President Ground Jury, FEI/Samsung, Oman 1997-1998 Course Designer, CSIO4*-W, Insterburg, Russia (east Prussia) 1998 Course Designer, CSIO3*-W, Almaty, Kazakhstan 1998-1999 Course Designer, CSIO2*-W, Minsk, Belarus 1998 Course Designer, CSI4*-W(cat A), Moskow, Russia 1998 Assistant CD, World Equestrian Games, Roma, Italy 1999 Course Designer, CSIO-W,Tashkent, Uzbekistan 1999 FEI Technical Delegate, Pan Arab Games, Amman, Jordan 1999 FEI Technical Delegate, FEI Challenge, AbuDabi, UAE 2000 Course Designer, Caucasus Cup, -

Sport Development in Kuwait: Perception of Stakeholders On

SPORT DEVELOPMENT IN KUWAIT: PERCEPTION OF STAKEHOLDERS ON THE SIGNIFICANCE AND DELIVERY OF SPORT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School at The Ohio State University By Badi Aldousari, M.A. * * * * * 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Packianathan Chelladurai, Advisor Dr. Donna Pastore __________________________ Advisor Dr. Janet Fink College of Education ABSTRACT The current study analyzed the perceptions of 402 stakeholders of Kuwaiti sport regarding the importance of three domains of sport (i.e., mass sport, elite sport, and commercial sport), and the relative emphases to be placed on each of these domains. The respondents were also asked to indicate the organizational forms (public, nonprofit, profit, public-nonprofit combine, and public-profit combine) best suited to deliver related sport services in the country. The stakeholder groups were administrators of federations (n = 57), administrators of clubs (n = 80), administrators of youth centers (n = 50), coaches of clubs (n = 78), coaches of youth centers (n = 57), and elite athletes (n = 70). The gender distribution of the respondents was 355 males and 47 females. They ranged in age from 19 years to 70 years for a mean of 39 years. The statistical procedures included exploratory principal component analysis, computation of Cronbach’s alpha, multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) followed by univariate analyses (ANOVA), and chi square analyses. The results provided support for the subscale structure of survey instrument modified from Cuellar (2003). Further analyses indicated that the six groups were almost unanimous in considering elite sport as more critical than the other two domains of sport. -

Abkürzungsverzeichnis

ABKÜRZUNGSVERZEICHNIS AAC Afro-Asian Cup of Nations AAG Afro-Asian Games AAT Addis-Ababa 25th Anniversary Tournament AC Argentine-Ministry of Education Cup AFC AFC IOFC Challenger-Cup AFT Artemio Franchi Trophy AG African Games ACC Amilcar Cabral Cup AGC Australien Bicentenary Gold Cup AHS 92nd Annivasary of FC Hajduk Split ALT Algeria Tournament AMC Albena Mobitel Cup ANC African Nations Cup ANQ African Nations Cup Qualifikation ARA Arab Cup ARC Artigas Cup ARQ Arab Cup Qualifikation ARR Artificial Riva Championship ASC Asien Cup ASG Asian Games ASQ Asien Cup Qualifikation AT Australia Tournament ATC Atlantic Cup BAC Baltic Cup BAT Belier d'Afrique Tournament BC British Championship BFC Bristol Freedon Cup BFT Burkina Faso Tournament BG Bolivar Games BHT Bahrain Tournament BI Beijing Invitational Cup BIC Brasil Independance Cup BKC Balkan Cup BLC Balkan Cup BNC Brasil Nations Cup BOT Botswana Tournament BSC Black Stars Championship BST Benin Solidarity Tournament BT Brunei Tournament BUT Bulgarien Tournament CA Copa Amerika CAC Caribbean Cup CAG Central African Games CAM Central American Games CAQ Copa Amerika Qualifikation CBC Carlsberg Cup CC Canada Cup CCC Copa Centenario de Chile CCF CCCF Championship CCQ Caribbean Cup / Copa Caribe Qualifikation CCU Caribbean Cup / Copa Caribe CCV Copa Ciudad de Valparaiso CDC Carlo-Dittborn-Cup CDM Ciudad de Mexiko CDP Copa de la Paz CDO Copa D´Oro CEC CECAFA Cup CED CEDEAU Tournament CEM CEMAC Cup CFN China Four Nations Tournament CGC Concacaf Gold Cup Championship CGQ Concacaf Gold Cup Qualifikation CHC Challenger Cup CIC China Invitional Cup CN Coupe Novembre COC Concacaf Championship CON Confederations Cup COS COSAFA Cup CPD Cope-Pinto-Duran CT Cyprus Tournament CUT Culture Cup CVT Cape Verde Tournament DC Dynasty Cup DCT Denmark Centenary Tournament DRK Dr. -

Why Developing Countries Are Just Spectators in the ‘Gold War’: the Case of Lebanon at the Olympic Games

Third World Quarterly ISSN: 0143-6597 (Print) 1360-2241 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctwq20 Why developing countries are just spectators in the ‘Gold War’: the case of Lebanon at the Olympic Games Danyel Reiche To cite this article: Danyel Reiche (2016): Why developing countries are just spectators in the ‘Gold War’: the case of Lebanon at the Olympic Games, Third World Quarterly, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1177455 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1177455 Published online: 06 Jun 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ctwq20 Download by: [65.112.10.82] Date: 06 June 2016, At: 06:23 THIRD WORLD QUARTERLY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1177455 Why developing countries are just spectators in the ‘Gold War’: the case of Lebanon at the Olympic Games Danyel Reiche Department of Political Studies and Public Administration, American University of Beirut, Lebanon ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY At the Olympic Games, there is an increasing gap between developed Received 10 February 2016 countries that are investing more and more government resources Accepted 8 April 2016 into sporting success, and developing countries that cannot afford KEYWORDS the “Gold War”, and are just spectators in the medal race. Based on Olympic Games studying a representative case, Lebanon, I investigate issues and sport interests of developing countries in the Olympics. On the political developing countries level, the main motivation for participation is global recognition. -

Sports Philately

/, / DMA FEB.V1DA SPORTS ORPORE SPORTS PHILATELISTS INTERNATIONAL PHILATELY Volume 28 May - June 1990 Number 5 FEATURE ARTICLES Alpine Skiing Championships 165 Atlanta 1996 170 1989 U.S. Postmarks (Baseball) 172 REGULAR COLUMNS Notes £ 182 Reviews 179 Sports and Olympics Exhibit Awards 182 DEPARTMENTS President' s Message 163 News of Our Members 183 New Sport Issues '-185* SPI Auction 188 161 SPORTS PHILATELISTS INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT: Mark C. Maestrone. 2824 Curie Place. San Diego, CA 92122 VICE-PRESIDENT: Edward B. Epstein. Bd. of Education. 33 Church St.. Paterson. NJ 07505 SEC-TREASURER: C. A. Reiss. 322 Riverside Dr.. Huron. OH 44839 DIRECTORS: Gtenn *• E»tus- Bo* 451, Westport NY 12993 v, John La Porta. PO Box 2286. La Grange, IL 60525 Sherwin D. Podolsky. 16035 Tupper St.. Sepulveda. CA 91343 Dorothy E. Weihrauch. Nine Island Ave.. Apt. 906. Miami Beach. FL 33139 Robert E. Wilcock. 24 Hamilton Cresent. Brentwood. CM14 1ES-. England Lester M. Yerkes. PO Box 424. Albuqueiqwe. NM 87103 AUCTIONS: Glenn A. Estus. Box 451. Westport. NY '2993 MEMBERSHIP: Margaret A. Jones, 3715 Ashford-Dunwoody Road, N.E., Atlanta, GA 30319 SALES DEPT: Jack W. Ryan, 140 W. Lafayette Road, Apt. 3, Medina, OH 44256 Sports Philatelists International is an independent, non-profit organization dedicated to the study and collecting of postage stamps and related collateral material dealing with sports (including Olympics) and recreation and to the promotion of international understanding and goodwill through mutual interest in philately and sports. Its activities are planned and carried on entirely by the unpaid, volunteer services of its members. All members in good standing receive the bi-monthly issue of Journal of Sports Philately. -

Inspired by 2012: the Legacy from the Olympic and Paralympic Games

Inspired by 2012: the legacy from the Olympic and Paralympic Games Fourth annual report – summer 2016 August 2016 Inspired by 2012: The legacy from the Olympic and Paralympic Games Fourth annual report – summer 2016 This document is available in large print, audio and braille on request. Please email [email protected] Cabinet Office 70 Whitehall London SW1A 2AS Publication date: August 2016 © Crown copyright 2016 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Any enquiries regarding this document/ To view this licence, publication should be sent to us at visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ publiccorrespondence@cabinetoffice. doc/open-government-licence/ gsi.gov.uk or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, This publication is available for download at or email: [email protected] www.gov.uk Contents Forewords 7 Executive Summary 10 Chapter 1: Introduction 12 Chapter 2: Sport and Healthy Living 14 Chapter 3: Regeneration of East London 30 Chapter 4: Economic Growth 44 Chapter 5: Bringing Communities Together 54 Chapter 6: The Legacy from the Paralympics 75 Glossary 89 Forewords 7 Foreword by Theresa May Rt Hon Theresa May MP Prime Minister London 2012 was an extraordinary moment diverse – from volunteering projects, to in our country’s recent history. Like many cultural initiatives promoting disabled artists, people I will never forget the excitement of to new standards around sustainability, and watching the world’s best athletes perform work to make our buildings and places more here on our shores, and the wonderful spirit accessible and inclusive – the list goes on. -

From Stoke Mandeville to Stratford: a History of the Summer Paralympic Games Brittain, I.S

From Stoke Mandeville to Stratford: A History of the Summer Paralympic Games Brittain, I.S. Published version deposited in CURVE May 2012 Original citation & hyperlink: Brittain, I.S. (2012) From Stoke Mandeville to Stratford: A History of the Summer Paralympic Games. Champaign, Illinois: Common Ground Publishing. http://sportandsociety.com/books/bookstore/ Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open sportandsociety.com FROM STOKE MANDEVILLE TO STRATFORD: A History of the Summer Paralympic Games A STRATFORD: TO MANDEVILLE FROM STOKE FROM STOKE MANDEVILLE As Aristotle once said, “If you would understand anything, observe its beginning and its development.” When Dr Ian TO STRATFORD Brittain started researching the history of the Paralympic Games after beginning his PhD studies in 1999, it quickly A history of the Summer Paralympic Games became clear that there was no clear or comprehensive source of information about the Paralympic Games or Great Britain’s participation in the Games. This book is an attempt to Ian Brittain document the history of the summer Paralympic Games and present it in one accessible and easy-to-read volume. -

Reference List

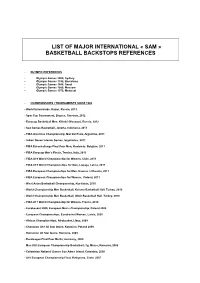

LIST OF MAJOR INTERNATIONAL « SAM » BASKETBALL BACKSTOPS REFERENCES • OLYMPIC REFERENCES - Olympic Games 2000, Sydney - Olympic Games 1992, Barcelona - Olympic Games 1988, Seoul - Olympic Games 1980, Moscow - Olympic Games 1976, Montreal • CHAMPIONSHIPS / TOURNAMENTS SINCE 1988 - World Universiade, Kazan, Russia, 2013 - Spar Cup Tournament, Brezice, Slovenia, 2012 - Eurocup Basketball Men, Khimki (Moscow), Russia, 2012 - Sea Games Basketball, Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011 - FIBA Americas Championship, Mar Del Plata, Argentina, 2011 - Indian Ocean Islands Games, Seychelles, 2011 - FIBA Eurochallenge Final Four Men, Oostende, Belgium, 2011 - FIBA Eurocup Men’s Finals, Treviso, Italy, 2011 - FIBA U19 World Championship for Women, Chile, 2011 - FIBA U19 World Championships for Men, Liepaja, Latvia, 2011 - FIBA European Championships for Men, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2011 - FIBA European Championships for Women, Poland, 2011 - West Asian Basketball Championship, Kurdistan, 2010 - World Championship Men Basketball, Kaisere Basketball Hall, Turkey, 2010 - World Championship Men Basketball, Izimir Basketball Hall, Turkey, 2010 - FIBA U17 World Championship for Women, France, 2010 - Eurobasket 2009, European Men’s Championship, Poland 2009 - European Championships, Eurobasket Women, Latvia, 2009 - African Championships, Afrobasket, Libya, 2009 - Champion U18 All Star Game, Katowice, Poland 2009 - Romanian All Star Game, Romania, 2009 - Euroleague Final Four Berlin, Germany, 2009 Men U20 European Championship Basketball, Tg. Mures, Romania, 2008 - Colombian -

Syria and the Olympics: National Identity on an International Stage

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Religious Studies 2014 Syria and the Olympics: National Identity on an International Stage Andrea L. Stanton University of Denver, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/religious_studies_faculty Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Stanton, A. L. (2014). Syria and the Olympics: National identity on an international stage. International Journal of the History of Sport, 31(3), 290-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2013.865018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Syria and the Olympics: National Identity on an International Stage Comments This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in the International Journal of the History of Sport on Feb. 4, 2014, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/ 09523367.2013.865018 Publication Statement Copyright held by the author or publisher. User is responsible for all copyright compliance. This article is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/religious_studies_faculty/8 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in the International Journal of the History of Sport on Feb. -

Inspired by 2012: the Legacy from the Olympic and Paralympic Games

Inspired by 2012: the legacy from the Olympic and Paralympic Games Fourth annual report – summer 2016 August 2016 Inspired by 2012: The legacy from the Olympic and Paralympic Games Fourth annual report – summer 2016 This document is available in large print, audio and braille on request. Please email [email protected] Cabinet Office 70 Whitehall London SW1A 2AS Publication date: August 2016 © Crown copyright 2016 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Any enquiries regarding this document/ To view this licence, publication should be sent to us at visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ publiccorrespondence@cabinetoffice. doc/open-government-licence/ gsi.gov.uk or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, This publication is available for download at or email: [email protected] www.gov.uk Contents Forewords 7 Executive Summary 10 Chapter 1: Introduction 12 Chapter 2: Sport and Healthy Living 14 Chapter 3: Regeneration of East London 30 Chapter 4: Economic Growth 44 Chapter 5: Bringing Communities Together 54 Chapter 6: The Legacy from the Paralympics 75 Glossary 89 Forewords 7 Foreword by Theresa May Rt Hon Theresa May MP Prime Minister London 2012 was an extraordinary moment diverse – from volunteering projects, to in our country’s recent history. Like many cultural initiatives promoting disabled artists, people I will never forget the excitement of to new standards around sustainability, and watching the world’s best athletes perform work to make our buildings and places more here on our shores, and the wonderful spirit accessible and inclusive – the list goes on.