Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deer Departed: a Study of the News Coverage of the Death of the Exmoor Emperor

Page 48 Journalism Education Volume 1 number 1 Deer departed: a study of the news coverage of the death of the Exmoor Emperor Alec Charles, University of Bedfordshire Abstract. This paper explores the socio-political symbol- ism which underpinned the UK’s mainstream national press coverage of the death of a red deer stag known as the Exmoor Emperor during the autumn of 2010. It em- ploys both qualitative and quantitative methods of con- tent analysis, and draws upon interviews with journalists and public figures involved in the telling of this story in order to suggest reasons behind the significant public and media interest in a narrative which had no ostensi- ble material impact upon a general readership. In doing so, it proposes that journalists, journalism students and journalism educators might significantly benefit from viewing the meaning of apparently trivial news stories through the frames of broader contexts and subtexts, and that such an approach might prove more enduringly useful than a pedagogical focus upon more ephemeral technicalities. The actor-comedian Steve Coogan in his online sitcom Mid Morning Matters (2011) and in the guise of his celebrated alter ego, North Norfolk Digital radio presenter Alan Partridge, imagined a scenario in which Britain’s “last osprey egg is stolen and scrambled for a Rus- sian oligarch’s breakfast – who eats it without one iota of remorse.” Coogan appears to be satirising the furore which had engulfed the UK news media just a few months earlier when another representative of Britain’s native fauna had been reported slaughtered, apparently at the hands of a wealthy foreign national. -

Anomalia Beau Séjour

SÉRIE SERIES SPEAKERS GUIDE – SÉRIE SERIES 2015 ANOMALIA PIERRE MONNARD – DIRECTOR – SWITZERLAND During his films studies in England, Pierre began his career as a director with his shorts films Swapped and Come Closer. Praised internationally, his films won more than twenty awards, including the Prix du Cinéma Suisse and the Léopard du Meilleur Court-Métrage at the Locarno Festival. After this success, Pierre directed adverts and music videos across Europe. His campaigns for MTV, Stella Artois and Carambar as well as his work with the French singer Calogero, have won numerous awards. In 2013, Pierre moves onto film direction, with his quirky comedy, Recycling Lily, which was critically acclaimed and won the Lauréat of the Fünf Seen Festival in Germany. Pierre is currently working on Anomalia with actors Natacha Régnier and Didier Bezace. The broadcasting of this fantasy series about the world of healers is expected for the beginning of 2016. JEAN-MARC FRÖHLE – PRODUCER, POINT PROD – SWITZERLAND Founded in 1996, Point Prod specialises in all types of production (dramas, documentaries, topical shows, magazines, TV, news). In 2005, the company started a development and production department for drama in television and films, lead by Jean-Marc Fröhle. Point Prod has since then become a major player in development, production and co-production of drama in Switzerland, in partnership with Swiss and European broadcasters. PILAR ANGUITA-MACKAY – SCREENWRITER, SWITZERLAND Pilar Anguita-MacKay has a Master’s in screenwriting from the University of Southern California (2001). As a screenwriter, she has won awards both in Europe and the United-States: in 2000, the Jack Nicholson Award for the script of A Rose for Maria; in 2007, best screenplay for La Mémoire des Autres, at the 3rd International Film Festival in Funchal. -

History Text 070803

Wiltshire Constabulary The Oldest and The Best 1839-2003The History of Wiltshire Constabulary Paul Sample Second Edition Wiltshire Constabulary Chief Constables 1839 - 2003 1839 - 1870 Captain Samuel Meredith RN 1870 - 1908 Captain Robert Sterne RN 1908 - 1943 Colonel Sir Höel Llewellyn DSO, DL 1943 - 1946 Mr W.T. Brooks (Acting Chief Constable) 1946 - 1963 Lt. Colonel Harold Golden CBE 1963 - 1979 Mr George Robert Glendinning OBE, QPM 1979 - 1983 Mr Kenneth Mayer QPM 1983 - 1988 Mr Donald Smith OBE, QPM 1988 - 1997 Mr Walter Girven QPM, LL B, FBIM 1997 - date Dame Elizabeth Neville DBE, QPM, MA, PhD © Paul Sample, 2003 Contents Foreword page 3 Introduction page 5 Riots and Rebellion page 6 The Magistrates take Action page 9 Starting from Scratch page 11 Rural Crime in the 1850s page 15 A Crime which Puzzled a Nation page 16 Policing and Sanitation in the 1860s page 18 Captain Sterne takes Command page 19 The Diary of a Rural Police Officer page 21 Long Hours and Low Life page 24 A Probationer’s Journal page 26 Bombs: Real and Imagined page 28 A Sad End to the Century page 30 The Death of a Hero page 31 A New Century, a new Chief Constable page 33 Marching to the Sound of Gunfire page 36 A Murder in the Family page 39 The Roaring 20s page 41 Calm before the Storm page 44 A Constabulary at War page 46 The Force Consolidates page 49 Policing the Swinging 60s page 50 the 1970s and ‘Operation Julie’ page 51 POLICING STONEHENGE page 53 The Murder of PC Kellam page 54 A Decade of Unrest page 55 Facing the Future page 59 Trains, Planes and Automobiles page 65 A Man’s Best Friend.. -

Tamworth Pigs Leaflet

Welcome to Tamworth TAMWORTH Pigs Tamworths are renowned for producing excellent quantities of both pork and bacon, due to their ability to achieve high body mass with little fat. In the 1990s the Tamworth came top in a taste test conducted by Bristol University. Today there are thought to be less than 300 registered breeding sows in the UK, leading to the breed being classified as ‘Vulnerable’ by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Where to see them… Tamworth Pigs can be seen at Ash End House Children’s Farm Middleton Lane, Middleton, near Tamworth, Staffordshire, B78 2BL Tel: 0121 329 3240 Email: [email protected] Website: www.childrensfarm.co.uk An introduction to the history of the Tamworth ”Sandyback” pig. If you require this information in another format or language please phone 01827 709581, or email [email protected] 9/17 (0746) www.visittamworth.co.uk The Tamworth Pig… Butch and Sundance- ‘The Tamworth Two’ A history Tamworth pigs are characterised by their long legs and neck, long narrow body, elongated snout and pricked up ears. However, the breed’s most distinctive feature is its ginger, orange-red coat. This colouration has led to to the breed being known as ‘Sandybacks’ or ‘Tamworth Reds’. Early breeds are believed to have had less prominent features and colours ranging from pale Two Tamworth Pigs escaped on their way to ginger, to dark mahogany, and some with black and an abattoir in Malmesbury, Wiltshire in red spots. Many of these traits are similar to those of wild English forest pigs. January 1998. -

Magazines Can Be Found Information About a Project on the Village Website

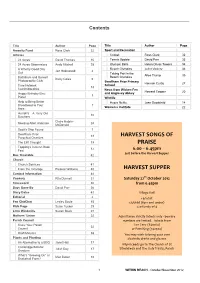

Ross’s Reflections Ross Clark 23 Contents Title Author Page Title Author Page Amenity Fund Ross Clark 22 Sport and Recreation Articles Cricket Ross Clark 32 24 Acres David Thomas 16 Tennis Update David Parr 33 24 Acres Observatory Andy Mitchell 28 Olympic Bells Helen Oliver-Towers 34 A Wherry Good Day Reach Olympics Juliet Vickery 34 Jen Holmwood 4 Out Taking Part in the Alice Trump 35 Bottisham and Burwell Reach Olympics Barry Coles 6 Photographic Club Swaffham Prior Primary Hannah Curtis 27 Care Network School 13 Cambridgeshire News from Wicken Fen Howard Cooper 20 Happy Birthday Else and Anglesey Abbey 3 Pieter Wildlife Help to Bring Better Hug a Nettle Joss Goodchild 14 Broadband to Your 7 Women’s Institute Area 22 Hurrell’s – A Very Old 10 Butchers Claire Halpin- Meeting Allen Alderson 24 McDonald Scott’s Ship Found 7 Swaffham Prior 13 Parochial Charities HARVEST SONGS OF The £50 Thought 19 PRAISE Topping’s Autumn Book 12 Fest 6.00 – 6.45pm just before the Harvest Supper Bus Timetable 42 Church Church Services 41 From the Vicarage Eleanor Williams 40 HARVEST SUPPER Contact Information 44 th Cookery Rita Dunnett 31 Saturday 27 October 2012 Crossword 30 from 6.45pm Days Gone By David Parr 26 Diary Dates 43 Village Hall Editorial 2 £6/adult Fen ChitChat Lesley Boyle 15 £3/child (6yrs and under) Kids Page Susie Tucker 29 £20 family of 4 Little Windmills Susan Bluck 27 Mothers’ Union 22 Admittance strictly tickets only - beware Parish Council numbers are limited. Tickets from Know Your Parish Jon Cane (741064) 22 Council or Pam King (742924) -

Chair Takes Champion

Autumn 2012 Chair takes Champion Congratulations to Tamworth Breeders‟ Club chairman Bill Howes on win- ning this year‟s Tamworth Champion of Champions competition. The finale to the Tamworth show- ing season is held every year at the Have your say! Royal County of Berkshire Show at Newbury. Unfortunately, many of Don’t forget that our the breeders with pigs which quali- Annual General fied for the final were unable to at- Meeting is coming up soon. tend, so only five pigs took part. Bill and Shirley Howes had two in the This year it is host- ring, and were joined by pigs from ed by club president Michele Baldock (Fairview Herd), Caroline Wheatley- Sharron Nicholas (Fairybank Herd), Hubbard in Warmin- ster, Wiltshire. The and Barbara Warren (Courtbleddyn date for your diary Herd). is October 21. The previous day, Bill and Shirley triumphed again, winning breed Bill Howes with judge Anne Petch, and champion with their sow, Stoneymoor Stoneymoor Melody 41 Melody 45, and and reserve with their gilt Stoneymoor Melody 41. Sadly, numbers were down once again, with just five pigs entered - three from the Howeses and two from Michele Baldock. Both Michele and Shar- ron Nicholas must be congratulated on making their debut at Newbury - and we trust they will make it an annual event. We hope both ladies en- joyed their experience and are now planning to get out and about even more with their pigs next year. Let‟s also hope that more club members will be encouraged to take part next year. If you would like a show “mentor” to help you get ready for the Caroline with some of her woodland pigs. -

VOLUME 18, ISSUE 1, February 2021

V O L U M E 1 8 , I S S U E 1 February 2021 ISSN 1948-352X Journal for Critical Animal Studies Editor Assistant Editor Dr. Amber E. George Nathan Poirier Galen University Michigan State University Peer Reviewers Michael Anderson Dr. Stephen R. Kauffman Drew University Christian Vegetarian Association Dr. Julie Andrzejewski Z. Zane McNeill St. Cloud State University Central European University Annie Côté Bernatchez Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II University of Ottawa Salt Lake Community College Amanda (Mandy) Bunten-Walberg Dr. Emily Patterson-Kane Queen’s University American Veterinary Medical Association Dr. Stella Capocci Montana Tech Dr. Nancy M. Rourke Canisius College Dr. Matthew Cole The Open University T. N. Rowan York University Sarat Colling Independent Scholar Jerika Sanderson Independent Scholar Christian Dymond Queen Mary University of London Monica Sousa York University Stephanie Eccles Concordia University Tayler E. Staneff University of Victoria Dr. Carrie P. Freeman Georgia State University Elizabeth Tavella University of Chicago Dr. Cathy B. Glenn Independent Scholar Dr. Siobhan Thomas London South Bank University David Gould University of Leeds Dr. Rulon Wood Boise State University Krista Hiddema Royal Roads University Allen Zimmerman Georgia State University William Huggins Independent Scholar Contents Issue Introduction: Getting Back to Our Roots p. 1-3 Amber E. George and Nathan Poirier Essay: Zoögogy of the Oppressed pp. 4-18 Ralph Acampora Essay: Silence Abets Violence: The Case for the Liberation pp. 19-51 Pledge nico stubler Essay: Being Consistently Biocentric: On the (Im)Possibility pp. 52-72 of Spinozist Animal Ethics Chandler D. Rogers Essay: Mediating a Global Capitalist, Speciesist Moral pp.73-99 Vacuum: How Two Escaped Pigs disrupted Dyson Appliances’ State of Nature Matthew David and Nathan Stephens-Griffin Poem: Sacred Space (An Environmental Poem) pp. -

TT Winter 2010

The Tamworth Breeders’ Club Winter 2010 Volume 5, Issue 2 TamworthTamworth Tamworths - The future’s orange! TrumpetTrumpet Happy Christmas! Bumper Christmas issue WWW ell, we’re back to having proper winters again and tough it is Inside this issue: on just about Tamworth Trifles 2 every pig keeper. With Chairman’s Message 3 forecasts pre- People 4 dicting more cold weather, Pork on the Menu 5 snow, ice and President’s Pronounce- 6 arctic winds, it’s ments good to know The Tamworth Two 7-9 that the great and the good are all ensconced in sunny Mexico discuss- ing global warming! And they only used the equivalent of 3,000 inter- News from Scotland 9-11 national flights to get there! Boris’ Big Day 11 2010 has been a fantastic year for Liz Shankland, broadcaster, writer, Successful Breeding 11-12 smallholder and winner of both the Tamworth Champion of Champi- ons and Tamworth Pig of the Year, so well done, Liz, the established Topsy-Turvy Year 12-13 showmen are looking over their shoulders. Sarah Harris 14-15 But as you will read inside, for every success Liz has enjoyed, there Show & Sale /AGM 16-17 have been some real downs too. So perhaps we should remember Pigs in Mythology 18-19 when looking at success not to be too jealous because for every swing, there’s a roundabout just around the corner. New Secretary 20 Everybody is struggling not only with the weather but with feed and bedding costs too so take a little time out this Christmas to really en- Tamworth Trumpet joy yourself with family and friends and make the most of the break. -

Space Odyssey: Voyage to the Planets

Introduction 02 BBC ONE Space Odyssey: Voyage To The Planets – Part 1 03 Space Odyssey: Voyage To The Planets – Part 2 04 BBC FOUR Space Odyssey: The Robot Pioneers 05 Take the journey further… 06 BBCi – Interactive TV bbc.co.uk/science The Tour Profiles of the main characters 07 The Astronauts Mission Control Space School – Turning actors into astronauts 08 The sets and costumes 09 Spacecraft: The facts 10 Space Oddities 14 Jargon Guides Space and Spacecraft 15 Mission Control 16 How we know what we know – the real missions behind Pegasus’ Journey 17 Series Advisors 19 Biographies Impossible Pictures 20 Production 21 Actors 22 Space Odyssey: Voyage to the Planets 01 The ultimate journey of human exploration comes to BBC One this November Imagine crashing through the acid storms of Venus, taking a space walk in the magnificent rings of Saturn, or collecting samples on the disintegrating surface of an unstable comet. From the makers of Walking With Dinosaurs, this magical drama-documentary series, narrated by David Suchet, takes viewers on the ultimate space flight and, by pressing the red button on the remote control, transports them right to the heart of the European Space Agency's mission control room. Seen through the eyes of five astronauts on a six-year mission to the new frontiers that make up our solar system, it reveals the spectacle – and the dangers – they face when landing on and exploring the exotic worlds of our neighbouring planets. Using the latest scientific findings and feature film digital effects, Space Odyssey: Voyage To The Planets is the ultimate grand tour, brought to life in a beautiful and moving journey packed with peril and excitement.