Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden-Section 106 Review Comment And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biting the Big Apple

Biting the Big Apple Curator Nicholas Baume talks to Fran Molloy lumnus Nicholas Baume has a new gallery space to curate: New York City. He has recently been art appointed Director and AChief Curator of the New York Public Art Fund, where he will guide the selection and installation of artworks by established and emerging artists in public spaces throughout the city. “The role does make me look at New York in a different way,” Baume says. “I’m really excited about it.” This is also the first time Baume has lived in New York, though his “Nicholas is like a son to me,” my lot in a professional direction, long association with the city’s cultural Kaldor says. “He is a brilliant young I felt that education for its own landscape started with a high school man who is very passionate about art.” sake was a very valuable thing.” art club trip in the early ’80s while an Baume and his two brothers were Baume has fond memories of his exchange student in Houston, Texas. similar in age and close friends with time at the University. “It was the first Graduating from the University Kaldor’s sons and spent a lot of time time I felt I was in an environment in 1987 with joint honours in Fine at the Kaldor home. But while his that nourished my intellectual Arts and Philosophy, Baume became brothers preferred the swimming and creative development. I loved an influential Australian curator, pool, Nicholas was drawn to Kaldor’s discovering the world of ideas.” exhibiting such artists as Andy extraordinary art collection. -

Leading Cultural Figures Attend Asia Society Art Gala, Launching Art Basel in Hong Kong

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LEADING CULTURAL FIGURES ATTEND ASIA SOCIETY ART GALA, LAUNCHING ART BASEL IN HONG KONG GUESTS INCLUDED ROBERT AND CHANTAL MILLER, JULIA AND VICTOR FUNG & BASSAM SALEM THIS YEAR’S HONOUREES FEATURED BHARTI KHER, LIU GUOSONG, TAKASHI MURAKAMI & ZHANG XIAOGANG (Hong Kong, 15 May 2014) More than four hundred of the world’s most distinguished collectors, curators, gallerists and dignitaries gathered this evening to honor four exceptional contemporary artists at the Asia Society’s second annual Art Gala, hosted by Ms. S. Alice Mong and Dr. Melissa Chiu at their spectacular Hong Kong Center. Kicking off Art Basel in Hong Kong, the evening celebrated world-renowned artists Bharti Kher, Liu Guosong, Takashi Murakami and Zhang Xiaogang for their extraordinary contributions to contemporary art in Asia. Guests were also treated to a private viewing of the first major solo exhibition of Xu Bing’s work in Hong Kong, currently on display through 31 August 2014. Notable guests included artists Li Songsong, Mariko Mori, Michael Joo and Song Dong. International collectors attended, including Deddy Kusama, Basma Al Sulaiman, Maggie Tsai, Alexandra Prasetio, and Bharat and Swati Bhise. Gallerists present included Nick Simunovic of Gasgosian Gallery, one of the evening’s hosts, Rachel Lehmann, Emmanuel Perrotin, Arne Glimcher, Marcia Levine, and Jane Lombard and Lisa Carlson. Supporters of Asia Society included Robert and Chantal Miller, Hal and Ruth Newman, Mitch and Joleen Julis. Other guests included actress Lynn Hsieh, Nam June Paik’s Nephew, Ken Hakuta, Director of Art Basel, Marc Spiegler, Managing Director of Christie’s Asia, Rebecca Wei, and Curator of UBS Art Collection, Stephen McCoubrey. -

US-China Museum Directors Forum Press

News Communications Department Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Contact: Elaine Merguerian 212.327.9313; [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Asia Society To Bring Together American and Chinese Museum Directors at Forum in Hangzhou and Shanghai, November 19–21 Book Launch Event and Discussion for Making a Museum in the 21st Century To Be Held at Shanghai's Long Museum, November 19, 6:30 p.m. Asia Society will convene the second U.S.-China Museum Leaders Forum, a part of the U.S.- China Forum on the Arts and Culture and the Asia Society Arts and Museum Network, in Shanghai and Hangzhou, November 19–21, 2014, to continue a dialogue that began with the first such gathering in Beijing in 2012. Nearly thirty American and Chinese museum directors, as well as several American art foundation leaders and Chinese cultural philanthropists, will meet to discuss potential areas for partnership and projects for collaboration. Co-convened by Orville Schell, Arthur Ross director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations, Asia Society, and Melissa Chiu, director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the U.S.-China Museum Leaders Forum aims to foster collaboration and exchange among museums in the two countries, first and foremost by enabling American museum leaders and their Chinese counterparts to connect on a personal level. The biennial Forum was initiated to address challenges faced by museums in China and ways to establish, operate, and sustain the thousands of new institutions the Chinese government plans to build in the next decade. -

Arts & Museum Summit

Arts & Museum Summit Asia Society Hong Kong Center November 21–22, 2013 What should museums of the twenty-first century look like? How should they display art and engage viewers? Is there a kind of disruption taking place within current thought that should be addressed? There is no doubt that most museum growth in the next few decades will be in Asia. Bringing together museum leaders from across Asia, Europe, and the United States, the Arts & Museum Summit explores the future of museums and navigates the challenges and opportunities in the cultural sector today; the developing museum ecology in Asia; and opportunities for professional development and partnerships among museums. Pre-registration online is required for the full program. The online registration will close on Thursday, November 14 so please plan accordingly. Thursday, November 21 3:30 p.m.–4:30 p.m. Registration 4:30 p.m.–6:00 p.m. Museum Leaders in Conversation: Making a Museum in the Twenty-first Century Leading museum professionals join in conversation on the future of museums in the twenty-first century. Free and open to the public. Please RSVP to [email protected] as seats are limited. Caroline Collier, Director, Tate National, London Glenn D. Lowry, Director, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Lars Nittve, Executive Director, M+, Hong Kong Wang Chunchen, Head of Curatorial Research, CAFA Art Museum, Beijing Moderated by Melissa Chiu, Museum Director and Senior Vice President, Global Arts and Cultural Programs, Asia Society Friday, November 22 8:00 a.m.–9:00 a.m. Registration 9:00 a.m. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Museum Leaders Gather in Hong Kong for First Asia Society Arts & Museum Summit, November 21-22, 2013

News Public Relations Department 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 www.AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Contact: Elaine Merguerian 212.327.9313; [email protected] Fax 212.517.8315 E-mail [email protected] Museum Leaders Gather In Hong Kong For First Asia Society Arts & Museum Summit, November 21-22, 2013 Recognizing Exponential Growth of Museums in Asia, Talks Focus on New Museum Models Hong Kong (November 21, 2013) — Museum leaders from across Asia, Europe, and North America gathered in Hong Kong today to explore ideas of new models for museums in the twenty-first century. Over 200 attendees are participating in the inaugural Asia Society Arts & Museum Summit, held at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center. The two-day event recognizes that the majority of new museums constructed in the next decade will be in Asia, where it has been estimated that over 3,000 new museums are being planned in China alone. Issues addressed at the summit include the challenges and opportunities in the cultural sector today; the developing museum ecology in Asia; and opportunities for professional development and partnerships among museums. “The Asia Society’s Arts & Museum Summit is designed to create powerful bonds between cultural leaders throughout Asia and America and build vital bridges of understanding through the arts,” says Asia Society President Josette Sheeran. “The Arts & Museum Summit will be held each year, building on Asia Society’s fifty-year history of fostering positive transformation in relations through arts and culture.” Where“The Asia and past America two Meet decades have seen enormous societal changes across Asia that have the potential to 725 Park Avenue New York,catalyze NY 10021 new-5088 thinking in the museum field. -

Curator Announced for the Honolulu Biennial's Third Edition

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Curator Announced for the Honolulu Biennial’s Third Edition Dr. Melissa Chiu to curate the Honolulu Biennial 2021, a multi-venue exhibition across the city of Honolulu Photo by Greg Powers. Courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. HONOLULU (October 15, 2019)––The Honolulu Biennial Foundation announces that the Honolulu Biennial 2021 will be curated by Dr. Melissa Chiu. The Honolulu Biennial, one of the largest major exhibition series in the world to focus on contemporary art practices of the Pacific, will take place February–April 2021. Its third edition will continue the Biennial’s mission to contribute to local and global dialogs by connecting perspectives, knowledge and creative expressions that are of the Pacific. First held in 2017, the Honolulu Biennial expanded for its second edition in 2019 to include works and performances from 47 artists and collectives across 12 iconic venues throughout Honolulu, including the Bishop Museum, Honolulu Museum of Art, Hawai’i State Art Museum, John Young Museum of Art at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa, Foster Botanical Garden, Aliʻiōlani Hale and McCoy Pavilion. HB19 was attended by nearly 115,000 visitors and generated an estimated $81.96 million for the state’s economy. In announcing the selection, Katherine Ann Leilani Tuider, Honolulu Biennial Foundation Executive Director and Co-founder, said: “We are excited to collaborate with Dr. Chiu on the third edition of the Honolulu Biennial. She brings significant insight, scholarship and passion. Dr. Chiu is key figure in building the global dialogue around contemporary art of the Asia-Pacific region, and we look forward to the conversations and connections she will advance for the Honolulu Biennial in 2021.” Jonathan Kindred, the Honolulu Biennial Foundation’s Board of Directors Chairman, noted: “We are extremely pleased to have Melissa join our team to lead the programming and presentation of HB21. -

Smithsonian Institution (SI) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017

Description of document: Smithsonian Institution (SI) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017 Requested date: 18-June-2017 Released date: 03-October-2018 Posted date: 15-October-2018 Source of document: Records Request Assistant General Counsel Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel MRC 012 PO Box 37012 Washington, DC 20013-7012 Fax: 202-357-4310 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 0 Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel VIA US MAIL October 3, 2018 RE: Your Request for Smithsonian Records (request number 48730) This responds to your request, dated June 18, 2017 and received in this Office on June 27, 2017, for "a copy of the meeting minutes from the Hirschhorn (sic) Museum Board of Trustees, during the time period 2013 to present." The Smithsonian responds to requests for records in accordance with Smithsonian Directive 807 - Requests for Smithsonian Institution Information (SD 807) and applies a presumption of disclosure when processing such requests. -

Asia Society Launches Asia Week in New York With

News Public Relations Department 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 www.AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Contact: Elaine Merguerian, 212-327-9271 Fax 212.517.8315 [email protected] E-mail [email protected] MUSEUMS, GALLERIES AND AUCTION HOUSES ANNOUNCE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS DURING ASIA WEEK NEW YORK, MARCH 20–28, 2010 Newly created AsiaWeekNewYork.org website launches New York, March 1, 2010—Asia Society is pleased to announce the detailed schedule for Asia Week New York, from March 20–28, 2010, which includes activities of over 40 of New York's major museums, art galleries and auction houses. As the city's largest and most diverse series of cultural events focusing on Asian art, the initiative—coordinated by Asia Society—builds on a decade-long history of New York dealers staging shows and auction houses conducting sales during spring Asia Week. This year represents the first time that a single institution has coordinated a city-wide effort among museums, auction houses, galleries and dealers. Details of the events, most of which are free and open to the public, are listed on the newly launched Asia Week New York website, www.AsiaWeekNewYork.org. Programming during the week will encompass public lectures, panel discussions, and museum and gallery exhibitions and receptions that promote understanding and appreciation of Asian art. The endeavor aims to look at new developments and trends in Asian art from multiple perspectives and at the broad range of traditional Asian arts being presented during March. “Asia Week brings together every major New York institution that has a significant interest in Asian art, organizing and formalizing the myriad activities relating to Asian art that occur each spring,” says Asia Society Museum Director Melissa Chiu. -

Distinguished Speakers from Hawai'i and Asia-Pacific Join Globally

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Distinguished Speakers from Hawai‘i and Asia-Pacific Join Globally Recognized Keynotes for Art Summit 2021 Internationally renowned artists Ai Weiwei and Theaster Gates, along with scholar Homi K. Bhabha, headline online event presented by Hawai‘i Contemporary (HONOLULU, Dec. 4, 2020) — Global artist Ai Weiwei, a leading cultural figure of his generation; artist Theaster Gates, a social innovator and placemaker; and scholar Homi K. Bhabha, a leading postcolonial theorist, will headline the Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit 2021, premiering online February 10–13, 2021. Making their Hawai‘i debuts, the three keynotes will be in conversation with Dr. Melissa Chiu, director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., and curatorial director for the Hawai‘i Triennial 2022, entitled Pacific Century – E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea. Presented by Hawai‘i Contemporary (formerly Honolulu Biennial Foundation), the inaugural Art Summit is a series of insightful and compelling talks, performances, film screenings and workshops, featuring renowned artists, curators, and thinkers from Hawai‘i, the Pacific, and beyond. The Art Summit will situate Hawai‘i at the center of high-caliber, global discourse around contemporary art and ideas with local and international audiences. “We’re thrilled to launch this inaugural Art Summit with three world-renowned thought leaders, who will set the tone for rigorous discussion in and around the Pacific,” said Katherine Don, executive director of Hawai‘i Contemporary. “With its mix of global, local, and indigenous voices, the Art Summit aims to engage audiences and illuminate new insights in international art practices and contemporary thinking.” The convening of artists and thinkers for Art Summit 2021 presents audiences with an opportunity for cultural exchange and understanding of a myriad of viewpoints. -

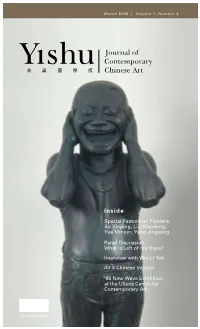

Inside Special Feature on Painters: Su Xinping, Liu Xiaodong, Yue Minjun, Yang Jingsong

March 2008 | Volume 7, Number 2 Inside Special Feature on Painters: Su Xinping, Liu Xiaodong, Yue Minjun, Yang Jingsong Panel Discussion: What is Left of the Hype? Interview with Wei-Li Yeh do it Chinese Version ’85 New Wave Exhibition at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 1 2 3 4 10 VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2, MARCH 2008 CONTENTS Editor’s Note 25 8 Contributors Special Feature on Painters 10 Su Xinping: Allegories of Loss Jonathan Goodman 18 New Pictures of the “Ugly Chinaman:” The Art of Liu Xiaodong Thorsten Botz-Bornstein 25 Interview with Yue Minjun Karen Smith 37 New Works/New Directions in the Art of Yang Jinsong 41 Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Symposium 41 What is Left of the Hype? Panel Discussion on China’s Art: Between New Beginnings and Commerce Artist Features 57 Wang Lang and Liu Xin Hua: Mission Accomplished Mathieu Borysevicz 64 Buried Treasures: An Afternoon with Wei-Li Yeh at the Cité Internationale des Art, Paris Joni Low 64 Do It 77 Why do it Chinese Version? Hu Yuanxing interviews Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hu Fang Reviews 84 A Chinese Frequency: Vital 07 – The Essence of Performance Rachel Lois Clapham 91 Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China Jonathan Goodman 91 98 A(n) (In)Decisive Act of Disclosure: Reflections on the ‘85 New Wave Exhibition at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing Paul Gladston 105 Chinese Name Index 98 Cover: Yue Minjun, Contemporary Terracotta Warriors (detail), 2005, bronze, 55 x 182 x 55 cm. Private Collection. Courtesy of the artist and AW ASIA, New York. -

Yang Fudong: Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo

News Communications Department 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Fax 212.517.8315 Contact: Elaine Merguerian 212.327.9271, [email protected] E-mail [email protected] ASIA SOCIETY MUSEUM PRESENTS FIRST-EVER MAJOR EXHIBITION OF ARTWORK FROM INDIA’S LATE MUGHAL PERIOD IN DELHI TRANSITION PERIOD FROM THE MUGHAL EMPIRE TO THE BRITISH RAJ EXPLORED PRINCES AND PAINTERS IN MUGHAL DELHI, 1707–1857 On view February 7 through May 6, 2012 Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 brings together 100 masterpieces created during an artistically rich period in India’s history. This major international loan exhibition provides a new look at an era of significant change during which the Mughal capital in Delhi shifted from being the heart of the late Mughal Empire to becoming the jewel in the crown of the British Raj. The exhibition includes jewel- like portrait paintings, striking panoramas, and exquisite decorative arts crafted for Mughal emperors and European Ghulam Ali Khan (active 1817–55). Nawab Muhammad Abd al-Rahman Khan of residents alike, as well as Jhajjar with his court and an East India Company political officer in the cool weather, historical photographs. 1852. Watercolor, body color, and gold H. 12 3⁄4 × W. 16 15⁄16 in. (32.4 × 43 cm). British Library, Add.Or.4681 Curated by William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma, the exhibition is accompanied by a 264-page illustrated book with essays by William Dalrymple, Yuthika Sharma, Jean Marie Lafont, Malini Roy, Sunil Sharma, and J.P. Losty, published by Asia Society Museum in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London.