Marketing Animals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 HSUS Annual Report

2015 Annual Report You Changed the World WITH YOUR SUPPORT, WE AND OUR AFFILIATES DIRECTLY HELPED 171,476 ANIMALS—AND DROVE CHANGE FOR MILLIONS MORE. With you by our side, 2015 was the highest impact year in the history of The Humane Society of the United States. Thank you for caring so much about animals. We could not have done this without you. As Kathy Klueh, a monthly donor from Florida, told us, “When we pool our resources we are a force that cannot be stopped.” HUMANE HEROES: Throughout this report, we’ve highlighted some of the people and organizations that helped us in 2015. ISLAND CONNECTION: OUR DONORS’ STORY In April, The HSUS and Humane Society International partnered with agencies in Puerto Rico to launch an island-wide initiative to help stray animals struggling to survive. In November, 15 donors came to help provide vaccines, flea/tick preventative and triage at a dog sanctuary, check in animals at an HSI spay/neuter clinic, visit shelters and assist with a stray dog feeding route. PICTURED ABOVE: Amanda Hearst, Steve Read and Daran Haber helped island dogs. NOT SHOWN: Pia Acker- man, Kami Anderson, Georgina Bloomberg, David Brownstein, Lisa Feria, Marion Look Jameson, Stacey Kivowitz, Colleen Lang, Marti Peretzman, Jerry Rosenthal, Bob Rhue and Courtney Stroum Meagher. OPPOSITE PAGE: Puppy mills campaign staffer Tara Loller visited with some of the dogs who will be helped by our work on the island. ON THE COVER: Cecil RIP July 1, 2015. This was an enormous year for our campaign to stop trade in products from endangered and rare animals. -

Front Lines NEWS, CAMPAIGNS, and ADVOCACY

Front Lines NEWS, CAMPAIGNS, AND ADVOCACY The Numbers Behind Canada’s Commercial SEAL SLAUGHTER MORE SENSELESS CRUELTY: THAN2MILLION In Canada’s commercial seal hunt, pups as young as % 12 days old are shot or clubbed to death for their KILLED 98 fur. Studies show that 82 percent of seals aren’t IN THE LAST killed with the first shot, and as many as two-thirds YOUNGER may still be conscious when skinned. 10 THAN 3 YEARS MONTHS OLD SEALING ACCOUNTS FOR LESS THAN .00005% OF CANADA’S $1.8 TRILLION GDP. NO ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATION: SEALING Sealing revenues are a small fraction of the millions .00005% of taxpayer funds the Canadian government spends OTHER to prop up the industry. For the few thousand fisher- 99.99995% men who participate in the hunt, an average of less than 5 percent of their incomes comes from killing seals. A DYING INDUSTRY: Since The HSUS and Humane Society International PELT PRICES KILL TOTAL renewed the Protect Seals campaign in 2004, global 32 demand for sealskins has plummeted and kills have dropped to a fraction of government quotas. We’re COUNTRIES HAVE BANNED SEAL 2012 now pushing for a government buyout of the in- PRODUCT TRADE SINCE 2006 dustry. Learn how you can help end the hunt for 65,235* good at hsi.org/protectseals. Russia, Nearly 6,000 Protect Seals Kazakhstan, businesses and and Belarus 750,000 people launches Canadian HSI helps seafood boycott; ban harp seal have joined the 450,000 stop China Mexico, Croatia, fur trade seafood boycott slaughter footage U.S. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Journal of Animal & Natural Resource

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL & NATURAL RESOURCE LAW Michigan State University College of Law MAY 2018 VOLUME XIV The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law is published annually by law students at Michigan State University College of Law. JOURNAL OF ANIMAL & The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law received generous support from NATURAL RESOURCE LAW the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and VOL. XIV 2018 host its annual symposium. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor David Favre, Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law, Michigan State University College of EDITORIAL BOARD Law, 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824, or by email to msujanrl@ gmail.com. 2017-2018 Current yearly subscription rates are $27.00 in the U.S. and current yearly Internet Editor-in-Chief subscription rates are $27.00. Subscriptions are renewed automatically unless a request AYLOR ATERS for discontinuance is received. T W Back issues may be obtained from: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Executive Editor & Notes Editor Buffalo, NY 14209. JENNIFER SMITH The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law welcomes the submission of articles, book reviews, and notes & comments. Each manuscript must be double spaced, in Managing Editor & Business Editor 12 point, Times New Roman; footnotes must be single spaced, 10 point, Times New INDSAY EISS Roman. Submissions should be sent to [email protected] using Microsoft Word or L W PDF format. -

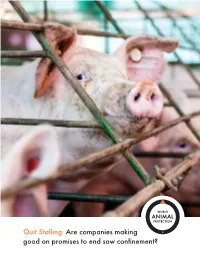

Quit Stalling: Are Companies Making Good on Promises to End Sow Confinement?

Quit Stalling: Are companies making good on promises to end sow confinement? 1 Introduction In the last decade, dozens of food companies publicly announced plans to end the use of gestation crates for pregnant pigs (sows) in their supply chains, sending a signal to the pork industry that the cruel practice would no longer be acceptable. The flurry of corporate commitments—most announced between 2012 and 2015—gained press attention and praise from advocates and consumers like you. Many companies set goals to end the use of gestation crates by their existing pork suppliers or identify new suppliers that could provide gestation-crate-free pork, typically with target dates by which implementation would be complete. As a result, major pork producers in the US publicly committed to finding solutions and shifting their breeding operations to group sow housing. But sadly, roughly ten years later, an estimated 3 out of 4 sows continue to spend significant portions of their lives confined to gestation crates with little space to move, let alone turn around. Corporate commitments to better sourcing practices were meant to apply pressure to producers to change their practices. Unfortunately, it appears that many companies have not been taking their own commitments seriously and risk breaking past promises to you, their customers. Several well-known brands, such as Marriott, Burger King, and Einstein Noah Bagels, set deadlines for achieving their gestation crate-free pork goals that have since passed, with little attention paid to acknowledging missed milestones. Many others, such as Wendy’s, Target, Quiznos, and Dine Brands (Applebee’s and IHOP), have deadlines that are fast approaching, but updates on their progress towards meeting their commitments, or on their work to move their suppliers forward, have not been forthcoming. -

Read Our Fact Sheet on the PIGS

Factsheet The PIGS Act Ending the use of extreme confinement of mother pigs What Does the Pigs in Gestation Stalls (PIGS) Act Do? This bill would ban the use of gestation stalls (also known as “crates”) for housing pregnant pigs and require that they have at least 36 square feet of space and the ability to lie down, stand up, and turn around freely. The two-foot by seven-foot crates currently used in the industry are so restrictive that pregnant pigs are essentially immobilized – sadly, they spend most of their lives kept in these horrific conditions. By forbidding this extreme form of confinement, Congress will level the playing field for all producers (nearly a dozen states restrict the practice and dozens of retailers have pledged to buy pork only from crate-free operations) and give consumers more confidence about the pig industry’s animal welfare standards. Why Support the PIGS Act? Keeping Pregnant Pigs in Extreme Confinement is Inhumane A breeding pig may spend up to three years intensively confined in a crate, and that’s the bulk of her entire lifespan. A pig can weigh 400 pounds, and the two-foot wide crate immobilizes her for months on end. The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act stipulates that pigs must be rendered insensible to pain prior to slaughter, and it only makes sense to have humane treatment standards for these animals for the duration of their lives. Pigs raised for meat are not kept in these needlessly restrictive crates, and neither should pregnant pigs. Major Retailers are Moving Away from Extreme Confinement Almost every major food retailer in the United States – from McDonald’s to Costco to Aramark – has agreed to phase out all purchasing of pork from farms that confine sows in gestation crates, with most policies taking effect in 2022. -

The Economics of Adopting Alternatives to Gestation Crate Confinement of Sows

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2011 The Economics of Adopting Alternatives to Gestation Crate Confinement of Sows The Humane Society of the United States Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/ hsus_reps_impacts_on_animals Part of the Agribusiness Commons, Animal Studies Commons, and the Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons Recommended Citation The Humane Society of the United States, "The Economics of Adopting Alternatives to Gestation Crate Confinement of Sows" (2011). IMPACTS ON FARM ANIMALS. 29. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/hsus_reps_impacts_on_animals/29 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An HSUS Report: The Economics of Adopting Alternatives to Gestation Crate Confinement of Sows Gestation crate confinement of sows Gestation crates are individual stalls with metal bars and concrete floors that confine pregnant pigs in the commercial pork production industry. Gestation crates measure 0.6-0.7 m (2.0-2.3 ft) by 2.0-2.1 m (6.6-6.9 ft), only slightly larger than the animals themselves, and restrict movement so severely that the sows are unable to turn around.1 In typical pig production facilities, gestation crates are placed side by side in long rows. They are primarily used on large-scale industrialized pig production operations, where thousands of pigs are produced annually in warehouse-like buildings. There are a number of significant animal welfare concerns associated with gestation crates for sows, * including tangible physical and psychological consequences. -

Download Preprint

Twitter Trends: #CageFree, #Vegan, #AnimalRights, and More! January 2021 Matt Montalbano & Jo Anderson, PhD Faunalytics Background Examining how public engagement with animal advocacy issues changes over time is key to our understanding of our target audience, and our understanding of the issues themselves. This goal is one that Faunalytics has pursued for many years, most notably through our 12-year Animal Tracker — an annual survey of U.S. adults’ attitudes and behavior related to animals and animal advocates. Ipsos (2020) recently published a visualization of U.S. Google Search data showing how levels of interest in vegan and plant-based diets have changed, state by state, over the period 2004 to 2019. While it is good to see the numbers increasing, this sort of analysis is difficult to interpret without other context. Is the increase in interest on par with other, non-animal-friendly diets? Do Google Searches mean people feel positive or negative about the diets, or are they just curious about what they are? The current analysis of a year of Twitter data provides a deeper look at the general public’s interest in animal-friendly diets, as well as other issues related to animal protection and advocacy. The time frame is shorter but the inferences we can draw are stronger. Key Findings Please note, when we talk about keywords throughout this report, it refers to words that are used in hashtags or anywhere in the body of a tweet. 1. Tweets pertaining to animal-friendly diets—especially veganism—are much more common than related concepts like animal advocacy, animal welfare, or cultured meat. -

Support Connecticut Farmers: Ban the Extreme and Unnecessary Confinement of Breeding Pigs

Support Connecticut Farmers: Ban the Extreme and Unnecessary Confinement of Breeding Pigs Support a ban on gestation crates, H.B. 5416 (Section 2), which will: 1) promote best practices that our local, Connecticut- based, sustainable farmers already follow, and 2) protect our family farmers by preventing large scale factory farms from coming to Connecticut (which would push out our family farmers). Legislative Proposal: amendment to cruelty statutes (Title 53, Chapter 945) that would “prohibit confinement of sows during gestation in a manner that prevents them from turning around freely, lying down, standing up, or fully extending their limbs”. Renowned animal scientist Dr. Temple Grandin states, “Gestation crates are a real problem. Basically you’re asking BILL STATUS: public hearing to be held on March 17, 2014 a sow to live in an airline seat… We’ve got to treat animals right, and gestation stalls have got to go.” THE ISSUE Due to the duration and severity of their confinement, pigs in gestation crates suffer among the worst abuse in all of industrial agribusiness. For several years, they are confined to crates that nearly immobilize them, enduring a cycle of repeated impregnation. These individual cages are approximately 2 feet wide x 7 feet long—so small the animals can’t even turn around or take more than a step forward or backward. Because they can’t move, they suffer muscle and bone weakness that often leads to lameness. And since these inquisitive animals are denied any mental stimulation, many become neurotic, engaging in repetitive coping behaviors, such as constantly biting the bars in front of them. -

The Food Industry Scorecard

THE FOOD INDUSTRY SCORECARD An evaluation of food companies’ progress making—and keeping— animal welfare promises humanesociety.org/scorecard Executive summary Most of the largest U.S. food companies have publicly pledged to eliminate certain animal abuses from their supply chains. But as countless consumers have asked: are they keeping their promises? For context, the vast majority of animals in our food system live Here’s the good news: that kind of radical view is out of in dismal conditions. Mother pigs are locked in gestation crates step with traditional American values. Agribusiness may see ani- so small they can’t turn around. Egg-laying hens are crammed mals as mere machines, but consumers don’t. into cages so tightly they can’t even spread their wings. And chickens in the poultry industry are bred to grow so large, so ɠ As the American Farm Bureau reports, nearly all consumers (95%) believe farm animals should be fast they suffer from agonizing leg disorders. treated well. It wasn’t always this way. Throughout history, animals hav- en’t been forced to endure such miserable lives. (And today, ɠ The Food Marketing Institute found that animal welfare is shoppers’ second most important social issue. there are certainly farmers who don’t use these abusive prac- tices.) But as agri-culture developed into agri-business, the ɠ The food industry analytics firm Technomic concluded industry’s relationship to animals became more severe. that for American restaurant patrons, concerns about animal cruelty outweigh those regarding the “Forget the pig is an animal,” urged Hog Farm Management environment, fair trade, local sourcing and other issues. -

Paul Shapiro by OUR HEN HOUSE Published March 8, 2014

Interview with Paul Shapiro By OUR HEN HOUSE Published March 8, 2014 Following is a transcript of an interview with PAUL SHAPIRO conducted by JASMIN SINGER and MARIANN SULLIVAN of Our Hen House, for the Our Hen House podcast. The interview aired on Episode 217. JASMIN: Paul Shapiro, the vice president of farm animal protection for the Humane Society of the United States, has played an integral role in numerous successful legislative and corporate campaigns to improve the plight of farm animals. His work has helped enact farm animal protection laws in California, Arizona, Michigan, Maine, Colorado, Oregon, and Ohio. He founded Compassion Over Killing in 1995 and served as its campaign director until January 2005. While there, he worked as a farm animal cruelty investigator and led initiatives such as the successful effort to end the use of the misleading Animal Care Certified logo on battery cage egg cartons nationwide. Paul has been interviewed in hundreds of print, broadcast, and online news sources as an authority on farm animal welfare and animal advocacy. He has also published dozens of articles about animal welfare in publications ranging from daily newspapers to academic journals. Learn more at humanesociety.org. Welcome back to Our Hen House, Paul. PAUL: Thanks so much, Jasmin and Mariann. It is an honor to be back. JASMIN: It is just an honor to have you. We are so excited to talk to you again. MARIANN: Yeah. Paul, you’re one of our favorite people, and you always know exactly what’s going on. You have a firm finger on the pulse of what’s going on in the farmed animal industry. -

Lucy Cain Hair and Makeup Designer

Lucy Cain Hair and Makeup Designer Agents Anna Hird Maternity Cover [email protected] Gemma Bicknell [email protected] Credits Film Production Company Notes EMILY Embankment Dir & Written by: Frances O'Connor (with Emma Mackey, 2021 Fionn Whitehead, Oliver Cohen Jackson, Alexandra Dorling, Gemma Jones & Adrian Dunbar ). THE SWEENEY Vertigo Films Dir: Nick Love Prod: Chris Simon (with Ray Winstone, Ben Drew, Damien Lewis, Steven Macintosh and Hayley Atwell) UNFINISHED Steel Mill Dir: Paul Andrew Williams SONG Productions Prod: Ken Marshall (with Terence Stamp, Vanessa Redgrave, Gemma Arterton and Christopher Ecclestone) Hollywood Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild Nomination - Best Contemporary Hair Styling (2014) SHAUN OF THE Working Title Films Dir: Edgar Wright DEAD Prod: Nira Park Pick-Ups (with Simon Pegg, Nick Frost, Lucy Davis and Dylan Moran) United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Company Notes SUSPICION Apple TV/Keshet TV Dir: Chris Long Prod: Darin McLeod (with Uma Thurman, Noah Emmerich and Kunal Nayyar) CRIMINAL: UK Netflix Dir: Jim Field Smith Series 2 Prod: Georgie Fallon (with Kit Harrington, Sharon Horgan and Sophie Okonedo) URBAN MYTHS: WHEN Fulwell 73 / Sky Dir: Sue Perkins BARBRA KISSED JOAN Prod: Amber Howorth (with Katherine Ryan, Jessica Barden and Laurie Kynaston) TWO WEEKS TO LIVE Sky / Kudos Film and Dir: Al Campbell Television Prod: Charlotte Surtees & Phil Temple (with Maisie