Avalanche Photodiodes Based on Mos2/Si Heterojunctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermionic and Gaseous State Diodes

THERMIONIC AND GASEOUS STATE DIODES Thermionic and gaseous state (vacuum tube) diodes Thermionic diodes are thermionic-valve devices (also known as vacuum tubes, tubes, or valves), which are arrangements of electrodes surrounded by a vacuum within a glass envelope. Early examples were fairly similar in appearance to incandescent light bulbs. In thermionic valve diodes, a current through the heater filament indirectly heats the cathode, another internal electrode treated with a mixture of barium and strontium oxides, which are oxides of alkaline earth metals; these substances are chosen because they have a small work function. (Some valves use direct heating, in which a tungsten filament acts as both heater and cathode.) The heat causes thermionic emission of electrons into the vacuum. In forward operation, a surrounding metal electrode called the anode is positively charged so that it electrostatically attracts the emitted electrons. However, electrons are not easily released from the unheated anode surface when the voltage polarity is reversed. Hence, any reverse flow is negligible. For much of the 20th century, thermionic valve diodes were used in analog signal applications, and as rectifiers in many power supplies. Today, valve diodes are only used in niche applications such as rectifiers in electric guitar and high-end audio amplifiers as well as specialized high-voltage equipment. Semiconductor diodes A modern semiconductor diode is made of a crystal of semiconductor like silicon that has impurities added to it to create a region on one side that contains negative charge carriers (electrons), called n-type semiconductor, and a region on the other side that contains positive charge carriers (holes), called p-type semiconductor. -

CHAPTER 11 HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector)

CHAPTER 11 HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector) HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector) is a completely new photomultiplier tube that incorporates a semiconductor element in an evacuated elec- tron tube. In HPD operation, photoelectrons emitted from the photo- cathode are accelerated to directly strike the semiconductor where their numbers are increased. Features offered by the HPD are extremely little fluctuation during the multiplication, high electron resolution, and excellent stability. © 2007 HAMAMATSU PHOTONICS K. K. 210 CHAPTER 11 HPD (Hybrid Photo-Detector) 11.1 Operating Principle of HPDs As shown in Figure 11-1, an HPD consists of a photocathode for converting light into photoelectrons and a semiconductor element (avalanche diode or AD) which is the target for "electron bombardment" by photo- electrons. The HPD operates on the following principle: when light enters the photocathode, photoelectrons are emitted according to the amount of light; these photoelectrons are accelerated by a high-intensity electric field of a few kilovolts to several dozen kilovolts applied to the photocathode; they are then bombarded onto the target semiconductor where electron-hole pairs are generated according to the incident energy of the photoelectrons. This is called "electron bombardment gain". A typical relation between this electron bom- bardment gain and the photocathode supply voltage is plotted in Figure 11-2. In principle, this electron bom- bardment gain is proportional to the photocathode supply voltage. However, there is actually a loss of energy in the electron bombardment due to the insensitive surface layer of the semiconductor, so their proportional relation does not hold at a low voltage. In Figure 11-2, the voltage at a point on the voltage axis (horizontal axis) where the dotted line intersects is called the threshold voltage [Vth]. -

Avalanche Diode Detector Unit

A large area avalanche photodiode detector system with USB interface 1. Introduction When measuring low light levels, a vacuum tube photomultiplier tube or some form of solid-state detector which relies on multiplication (e.g. Avalanche diode, Geiger avalanche diode, silicon photomultiplier) is normally used. Vacuum tube photomultipliers have the advantage that a large photosensitive area is available, in contrast to most solid-state devices, which, in general, allow detection over a small area. Avalanche photodiodes make excellent detectors, and here we describe a detector assembly developed around a large area device, 10 mm diameter. This detector unit is designed to detect low light levels and is based around a detector module, commercially available from AP Technology, (www.advancedphotonix.com) part# 197-70-74-661. The detector module is supplied as just that, a small box with flying leads, requiring appropriate low voltage dc power supplies. It does include a thermoelectric cooler and the avalanche diode’s high voltage bias supply. Here we describe how this module was integrated in a photo-detection subsystem, powered from the mains and controlled either from an internal potentiometer or through a computer interface. The completed unit can operate as a stand-alone, manually adjusted unit and powered from a +5V / 2.5A power supply, providing an analogue output in the range 0 to +1V into a 50 Ω (or greater) load over a typical 10 MHz bandwidth. It can also operate as a USB-controlled device, where the detector gain can be remotely set and where output readings and operating conditions can be monitored. -

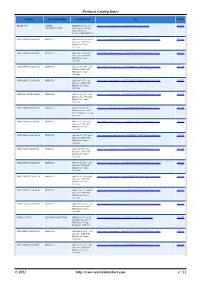

Products Catalog Index

Products Catalog Index PART NO. MANUFACTURER DESCRIPTION URL PRICE DFLR1400-7 DIODES DFLR1400 Series 1 A http://www.searchdatasheet.com/DFLR1400-7-datasheet.html QUOTE INCORPORATED 400 V Surface Mount Glass Passivated Rectifier-POWERDI-123 GRM155R61C474KE01D MURATA 0402 0.47 uF 16 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R61C474KE01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R60J102KA01D MURATA 0402 1 nF 6.3 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R60J102KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R61C222KA01D MURATA 0402 2.2 nF 16 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R61C222KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R71C102KA01D MURATA 0402 1 nF 16 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R71C102KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X7R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM1885C1H1R5CA01D MURATA 0603 1.5 pF 50 V ±0.25 http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM1885C1H1R5CA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE pF Tolerance C0G SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R60J334KE01D MURATA 0402 0.33 uF 6.3 V http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R60J334KE01D-datasheet.html QUOTE ±10% Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R71H222JA01D MURATA 0402 2.2 nF 50 V ±5% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R71H222JA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X7R SMT Multilayer Ceramic Capacitor GRM155R61A103KA01D MURATA 0402 10 nF 10 V ±10% http://www.searchdatasheet.com/GRM155R61A103KA01D-datasheet.html QUOTE Tolerance X5R SMT Multilayer Ceramic -

Circuits for High-Efficiency Avalanche-Diode Oscillators

1060 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MICROWAVE THEORY AND TECHNIQUES, VOL. MTT-17, NO. 12, DECEMBER 1969 Circuits for High-Efficiency Avalanche- Diode Oscillators W. J. EVANS Absfract—This paper describes and analyzes the circuits which have II. THE TRAPATT MODE been used successfully for TRAPATT oscillator studies. The results lead In order to understand the operation of high-efficiency to a better understanding of the TRAPATT oscillator and yield a simple model of the oscillator which is useful for circuit design. oscillators, it is necessary to understand what happens when The circuit characteristics of ms experimental TRAPATT oscillator large RF voltage swings exist across an IMPATT diode. are determined from measurements on the circuits and from equivalent Therefore, this section will begin with a review of the large- circuit model calculations. The following conclusions can be drawn from signal behavior of an IMPATT oscillator. the analysis. First, the avalanche diode requires sufficient capacitance near Fig. l(a) is a plot of the field profile and carrier densities the diode to sustain the high-current state required for TRAPATT oper- in an oscillating IMPATT diode at a particular point in ation. Seeondly, at a distance from the diode corresponding to approx. time. The profile shown here is for a 6-GHz n+-p-p+ epi- inmtely one half-wavelength at the TRAPATT frequency the transmission taxial germanium diode [4]. The plots are made for the par- ~me containing the diode should be terminated by a low-pass filter. The ticular point in the RF voltage and current waveforms indi- function of the filter is to pass the TRAPATT frequency and to provide a cated by the squares in Fig. -

Noise in Avalanche Transit-Time Devices

1674 PROCEEDINGS OF THE IEEE, VOL. 59, NO. 12, DECEMBER 1971 for receiving arrays,” ZEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. (Commun.), [22] C. J. Drane, Jr., and J. F. McIlvenna, “Gain maximization and VO~.AP-14, NOV.1966, pp. 792-794. controlled null placement simultaneously achievedin aerial array [9] A. I. Uzkov, ‘‘An approach to the problem of optimum directive patterns,” Air Force Cambridge Res. Labs., Bedford,Mass., antenna design,” C. R. Acad. Sci. USSR., vol. 35, 1946, p. 35. Rep. AFCRL-69-0257, June 1969. [lo] A. Bloch, R. G. Medhurst, and S. D. Pool, “A new approach to [23] R. F. Hamngton, “Matrixmethods for field problems,” Proc. the design of superdirective aerial arrays,” Proc. Znst. Elec. Eng., ZEEE, vol. 55, Feb. 1967, pp. 136-149. VO~.100, Sept. 1953, pp. 303-314. [24] J. A. Cummins,“Analysis of a circulararray of antennas by [ll] M.Uzsoky and L. Solymar,“Theory of superdirectivelinear matrix methods,” Ph.D. dissertation, Elec. Eng. Dept., Syracuse arrays,” Acta Phys. (Budapt), vol. 6, 1956, pp. 185-204. University, Syracuse,N. Y., Dec. 1968. [12] C. T. Tai, “The optimum directivity of uniformly spaced broad- [25] B. J. Strait and K. Hirasawa, “On radiation and scattering from sidearrays ofdipoles,” ZEEE Trans. Antennas Propgat., vol. arrays of wire antennas,” Proc. Nut. Elec. Con$, vol. 25, 1969. AP-12, July 1964, pp. 447-454. [26] A.T. Adams and B. J. Strait, “Modernanalysis methods for [13] D. K. Cheng and F. I. Tseng, “Gain optimization for arbitrary EMC,” ZEEEIEMC Symp. Rec., July 1970, pp. 383-393. antenna arrays,’’ ZEEE Trans. -

FAGOR Avalanche Rectifiers

Application Note Fagor Electrónica Semiconductores Avalanche Rectifiers Avalanche Rectifiers are diodes that can tolerate voltages above the repetitive reverse maximum blocking voltage (Vrrm) and, furthermore, dissipate a specified maximum energy during these pulses. Here we describe how these diodes differ from normal rectifiers and the applications to which they are suited. Introduction Rectifiers are two-terminal devices that are used to conduct current in one direction but block in the other according to a characteristic of the type shown in Figure 1. Standard rectifiers operate stably in either the Reverse Blocking Mode or in the Forward Conducting Mode. In the first case, only a very small leakage current flows so that power dissipation in the device is not important. In the second case, the forward voltage is more than a volt so considerable power may be dissipated in the device, but provided the heat is extracted efficiently the junction temperature will not exceed the maximum rated value and the device will be stable. I Figure 1 Modes of Operation within the I-V characteristic of Rectifiers. V Forward Concucting Avalanche Reverse Blocking Mode Mode Mode Further limitations apply when the rectifier is switched from conducting a large forward current to blocking a large reverse voltage. During a time after switching, the current that flows in the reverse direction greatly exceeds the reverse leakage value. Even if the delay in establishing the blocking condition is not important in the application, the additional power dissipated may cause the device to overheat and eventually fail. The recovery time depends strongly on the forward current before switching but standard conditions have been established to measure the Trr parameter (Typically: I F=0.5A switched to I R=1A at t=0 and recuperation defined has having occurred when I R=0.25A). -

Practical Design Techniques for Power and Thermal

INDEX Subject Index A digital temperature sensors, 6.36-37 AAVID 573300: temperature sensor 10-bit ADC, heat sink: characteristics, 6.37 thermal resistance vs. airflow, 8.57 AD77XX: for TO-263, 8.57 high resolution ADC, 6.13-15 AAVID 582002B12500: high resolution ADCs, 6.11 heat sink: AD7705: thermal resistance vs. airflow, 8.55 16-bit sigma delta ADC, 7.11 for TO-220, 8.54 applications, 7.13 AAVID Thermal Technologies, Inc., 8.58 battery monitor circuit, 7.13 Absolute voltage output sensor, 6.24-25 cell monitor, battery charger, 7.13 EMI/RFI effects, 6.25 programmable gain amplifier, 7.13 with shutdown, 6.23 specifications, 7.13 thermal time constant, 6.25-26 AD7817/7818/7819: AD580: digital temperature sensors, 6.36-37 three-terminal bandgap reference, 2.5-6 temperature sensor 10-bit ADC, serial Brokaw cell, 2.6 interface, characteristics, 6.37 AD586: AD22103, ratiometric output sensor, 6.22-23 buried zener reference, 2.10 ADC: long-term drift performance, 2.14 10-bit, series temperature sensor, 6.36-37 low tolerance, 2.14 16-bit, sigma delta, 7.11 AD587, buried zener, noise reduction pin, 22-bit, 2.23 2.18 high resolution, 6.13-15 AD588: resistance temperature detector buffer amplifier, 2.16 interfacing, 6.15 buried zener reference, 2.10 high speed, EMI/RFI noise, 8.73 long-term drift performance, 2.14 on-chip temperature sensors, 6.36-37 low tolerance, 2.14 sigma-delta: AD592, current output sensors, 6.21-22 AD780-driven, 2.23-24 AD594, Type J thermocouple, 6.10 internal digital filter, 2.21 AD594/595: noise, 2.20 circuit, 6.10 reference -

Introduction to the Silicon Photomultiplier (Sipm) AND9770/D

ON Semiconductor Is Now To learn more about onsemi™, please visit our website at www.onsemi.com onsemi and and other names, marks, and brands are registered and/or common law trademarks of Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC dba “onsemi” or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. onsemi owns the rights to a number of patents, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, and other intellectual property. A listing of onsemi product/patent coverage may be accessed at www.onsemi.com/site/pdf/Patent-Marking.pdf. onsemi reserves the right to make changes at any time to any products or information herein, without notice. The information herein is provided “as-is” and onsemi makes no warranty, representation or guarantee regarding the accuracy of the information, product features, availability, functionality, or suitability of its products for any particular purpose, nor does onsemi assume any liability arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit, and specifically disclaims any and all liability, including without limitation special, consequential or incidental damages. Buyer is responsible for its products and applications using onsemi products, including compliance with all laws, regulations and safety requirements or standards, regardless of any support or applications information provided by onsemi. “Typical” parameters which may be provided in onsemi data sheets and/ or specifications can and do vary in different applications and actual performance may vary over time. All operating parameters, including “Typicals” must be validated for each customer application by customer’s technical experts. onsemi does not convey any license under any of its intellectual property rights nor the rights of others. -

Semiconductor-Based Detectors

Chapter 4: Semiconductor-based detectors Sergio Cova, Massimo Ghioni Politecnico di Milano Dipartimento di Elettronica, Informazione e Bioingegneria Piazza Leonardo da Vinci, 32 20133 Milano - Italy [email protected] Mark A. Itzler Princeton Lightwave, Inc. 2555 US Route 130 S. Cranbury, NJ 08512 [email protected] Joshua C. Bienfang, Alessandro Restelli National Institute of Standards and Technology, Joint Quantum Institute 100 Bureau Dr. Gaithersburg, MD 20899 [email protected] 1 Section 4.1 – Photon Counting: when and why There is nowadays a widespread and growing interest in low-level light detection and imaging. This interest is driven by the need for high sensitivity in various scientific and industrial applications such as fluorescence spectroscopy in life and material sciences, quantum computing and cryptography, profiling of remote objects with optical radar techniques, particle sizing, and more. In particular, the use of fluorescence-lifetime spectroscopy as both an analytical and research tool has increased markedly in recent years finding remarkable applications in chemistry, biochemistry, and biology. Photon counting has long been recognized as the technique of choice for attaining the ultimate sensitivity in measurements of optical signals. However, advanced analog detectors (such as back- illuminated charge-coupled devices (CCDs)) with ultra-low dark current can also be used in some instances to measure very weak photon fluxes. A basic issue must therefore be clearly addressed: when and why are photon-counting detectors advantageous? For applications where the measurement time is very short or the arrival time of the optical signal must be known with high precision (e.g. high-frame-rate imaging, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), or fast optical coincidences), photon-counting detectors have an advantage over analog detectors, which have electronic readout noise in addition to dark-current noise. -

ON Semiconductor Is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer

ON Semiconductor Is Now To learn more about onsemi™, please visit our website at www.onsemi.com onsemi and and other names, marks, and brands are registered and/or common law trademarks of Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC dba “onsemi” or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. onsemi owns the rights to a number of patents, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, and other intellectual property. A listing of onsemi product/patent coverage may be accessed at www.onsemi.com/site/pdf/Patent-Marking.pdf. onsemi reserves the right to make changes at any time to any products or information herein, without notice. The information herein is provided “as-is” and onsemi makes no warranty, representation or guarantee regarding the accuracy of the information, product features, availability, functionality, or suitability of its products for any particular purpose, nor does onsemi assume any liability arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit, and specifically disclaims any and all liability, including without limitation special, consequential or incidental damages. Buyer is responsible for its products and applications using onsemi products, including compliance with all laws, regulations and safety requirements or standards, regardless of any support or applications information provided by onsemi. “Typical” parameters which may be provided in onsemi data sheets and/ or specifications can and do vary in different applications and actual performance may vary over time. All operating parameters, including “Typicals” must be validated for each customer application by customer’s technical experts. onsemi does not convey any license under any of its intellectual property rights nor the rights of others. -

Transient Voltage Suppression Diode Application Notes

Effective December 2017 Technical Note 4048 Supersedes 2009 Transient Voltage Suppression diode application notes Overview Transient Voltage Suppression (TVS) diodes are useful in protecting electronic circuits from electrostatic discharge (ESD). The TVS diodes used for ESD protection are silicon-avalanche diodes. With a high impedance at the stand-off voltage and low impedance at the breakdown voltage, silicon-avalanche diodes are well suited for ESD protection. To better understand the TVS diode’s application for ESD protection, one must first understand how the diode works in general and, in particular, how the silicon-avalanche diode differs from the Zener diode. Silicon-Avalanche Diode vs. Zener Diode Silicon-avalanche diodes (SADs) are similar to Zener diodes. SADs are even sometimes mistaken for Zener diodes because of their TVSA Family: available in 0201 and 0402 SMD packages similar electrical characteristics. The Zener diode and SADs both conduct in the reverse direction if the voltage through it exceeds a set breakdown voltage. Zener diode: This corresponds to the transport of electrons from the positively doped side of the diode to the holes of the negatively doped side of the diode (Figure 1). SAD: A similar transport of electrons occurs called the avalanche effect. The only real difference between the Zener diode and SAD is the length of the p-n equilibrium channel (Figure 2). Here the only real difference is seen is the temperature coefficients: • Zener diodes have a negative temperature coefficient, (resistance decreases and temperature increases) • SADs have a positive temperature coefficient (resistance increases and temperature increases) This, however, is only important in temperature sensitive applications.