How Urban Planners Can Learn from Hip-Hop Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 CAPTURE THE FLAG Actors: Rasmus Hardiker. Sam Fink. Paul Kelleher. Adam James. Derek Siow. Andrew Hamblin. Oriol Tarragó. Bryan Bounds. Ed Gaughan. Actresses: Lorraine Pilkington. Philippa Alexander. Jennifer Wiltsie. CARE OF FOOTPATH 2 Actors: Deepp Pathak. Jaya Karthik. Kishan S. S.. Dingri Naresh. Actresses: Avika Gor. Esha Deol. CARL(A) Actors: Gregg Bello. Actresses: Laverne Cox. CAROL Actors: Jake Lacy. John Magaro. Cory Michael Smith. Kevin Crowley. Nik Pajic. Kyle Chandler. Actresses: Cate Blanchett. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

Amici Curiae Brief of Erik Nielson, Charis E

No. 15-666 __________________________________________ In the Supreme Court of the United States _____ ____ TAYLOR BELL, Petitioner, V. ITAWAMBA COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, Respondent. _____ ____ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court Of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ______ ___ AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF ERIK NIELSON, CHARIS E. KUBRIN, TRAVIS L. GOSA, MICHAEL RENDER (AKA “KILLER MIKE”) AND OTHER SCHOLARS AND ARTISTS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER _____ ____ CHARLES “CHAD” BARUCH Counsel of Record COYT RANDAL JOHNSTON JR. JOHNSTON TOBEY BARUCH 3308 Oak Grove Avenue Dallas, Texas 75204 (214) 741-6260 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae __________________________________________ LEGAL PRINTERS LLC, Washington DC ! 202-747-2400 ! legalprinters.com i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................ i Table of Authorities ................................................... ii Interests of Amici Curiae ........................................... 1 Summary of Argument .............................................. 3 Argument .................................................................... 6 A. “Fight the power”: The politics of hip hop .......... 6 B. “Put my Glock away, I got a stronger weapon that never runs out of ammunition”: The non- literal rhetoric of hip hop .................................. 12 C. “They ain’t scared of rap music—they scared of us”: Rap’s bad rap .............................................. 19 Conclusion ............................................................... -

Scarface, Never Snitch (Feat

Scarface, Never Snitch (feat. Beanie Sigel, The Game) [Scarface] Niggaz forget about the streets but when they rap they songs They claim they tote the heat, they quick to clap they guns In interviews be braggin bout the crack they slung But when it's war, these cowards never blast, they run The fuck you think you foolin dog? I live this shit I know it when niggaz fake it - I live this shit You can front it all you want but when yo ass gets hot Then you can rest assured nigga - yo ass gets got I'm sayin that to say this - I can plot those hits I'm connected in every city on capo shit I ain't even gotta say these niggaz know my ties A nigga made, therefore whoever cross gon die Money changin motherfuckers, makin hoes grow nuts You a bad motherfucker, you don't give no fuck Let me snap you back to reality dude, shit's real You a target, niggaz in Houston want you killed Facemob until it's over, Southside the pipes Dirty Third in this bitch, J. Prince for life Dedicated to these niggaz live and breathe that shit Let the real niggaz shout it out, scream that shit [Chorus: Scarface] I never snitch, I never lie I'm not a bitch, I rather die Can't nothin change me, not even time I make the money, money don't make me a dime [x2] [Beanie Siegel] Facemob! Yeah B. Sieg baby, I'm back up in this bitch like what Fresh out the pen, once again I'm here to grab my nuts I am hell for real - you doubt it nigga? call my bluff Only respect men that's real, you coward rat-ass fucks Who raised you niggaz? Yo father probably hate yo guts Mad he didn't double -

He's Been Fighting for His Career for Near Fifteen Years. Never Afraid of Change, He's Sticking and Moving and Going For

! Ü HE’S BEEN FIGHTING FOR HIS CAREER FOR NEAR FIFTEEN YEARS. NEVER AFRAID OF CHANGE, HE’S STICKING AND MOVING " AND GOING FOR HIS. BUT TIME WEARS HARD ON THE BOOGIE DOWN STREETS. HAS HAD HIS HITS, BUT HE’S TAKEN SOME, TOO. SALTER S JEFFERY // IMAGE GOLIANOPOULOS THOMAS WORDS Ü " ! XXL MAGAZINE 000 ! Ü " " t’s seven o’clock in the evening, album past 500,000 in sales, earning him his and recent audience-expanding cameos with and Fat Joe needs a designated first gold plaque. Three years later, in 2001, Jennifer Lopez, Paris Hilton and Ricky Martin, driver. The 36-year-old rapper isn’t when Murder Inc. was dominating hip-hop he J.O.S.E. remains his only platinum record. inebriated, but he drives like Ricky released “What’s Luv?” a frothy Irv Gotti pro- Joe is well aware of his SoundScan struggles. Bobby after one too many Miller duction that propelled Jealous Ones Still Envy “The strangest thing in the whole universe,” Lites. He breaks too suddenly, ac- to platinum status. Today, the South runs hip- he says, “is Fat Joe being a household name, celerates too carelessly and nearly hop, and, of course, Fat Joe has noticed. making the biggest hit records in the history of crashes too often. He’s also eas- “Joe’s good at reading the future,” says mankind, and not selling that many records. It ily distracted by the radio (Nelly Miami-based DJ Khaled, who’s known him for will be reevaluated years from now.” Furtado’s “Promiscuous” brings more than 10 years. -

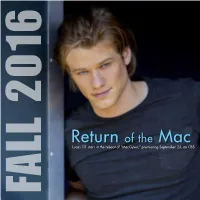

Return of The

Return of the Mac Lucas Till stars in the reboot of “MacGyver,” premiering September 23, on CBS. FALL 2016 FALL “Conviction” ABC Mon., Oct. 3, 10 p.m. PLUG IN TO Right after finishing her two-season run as “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” Hayley Atwell – again sporting a flawless THESE FALL PREMIERES American accent for a British actress – BY JAY BOBBIN returns to ABC as a smart but wayward lawyer and member of a former first family who avoids doing jail time by joining a district attorney (“CSI: NY” alum Eddie Cahill) in his crusade to overturn apparent wrongful convictions … and possibly set things straight with her relatives in the process. “American Housewife” ABC Tues., Oct. 11, 8:30 p.m. Following several seasons of lending reliable support to the stars of “Mike & Molly,” Katy Mixon gets the “Designated Survivor” ABC showcase role in this sitcom, which Wed., Sept. 21, 10 p.m. originally was titled “The Second Fattest If Kiefer Sutherland wanted an effective series follow-up to “24,” he’s found it, based Housewife in Westport” – indicating on the riveting early footage of this drama. The show takes its title from the term used that her character isn’t in step with the for the member of a presidential cabinet who stays behind during the State of the Connecticut town’s largely “perfect” Union Address, should anything happen to the others … and it does here, making female residents, but the sweetly candid Sutherland’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development the new and immediate wife and mom is boldly content to have chief executive. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

Considering the Worthy Sacrifice Hip Hop Artists May Need to Make to Reclaim the Heart of Hip Hop, Its People

It’s Not Me, It’s You: Considering the Worthy Sacrifice Hip Hop Artists May Need to Make to Reclaim the Heart of Hip Hop, its People by Sharieka Shontae Botex April, 2019 Director of Thesis: Dr. Wendy Sharer Major Department: English The origins of Hip Hop evidence that the art form was intended to provide more than music to listen to, but instead offer art that delivers messages on behalf of people who were not always listened to. My thesis offers an analysis of Jay-Z and J. Cole’s lyrical content and adds to an ongoing discussion of the potential Hip Hop artists have to be effective leaders for the Black community, whose lyrical content can be used to make positive change in society, and how this ability at times can be compromised by creating content that doesn’t evidence this potential or undermines it. Along with this, my work highlights how some of Jay-Z and J. Cole’s lyrical content exhibits their use of some rhetorical strategies and techniques used in social movements and their use of some African American rhetorical practices and strategies. In addition to this, I acknowledge and discuss points in scholarship that connect with my discussion of their lyrical content, or that aided me in proposing what they could consider for future lyrical content. I analyzed six Jay-Z songs and six J. Cole songs, including one song from their earliest released studio album and one from their most recently released studio album. I examined their lyrical content to document responses to the following questions: What issues and topics are discussed in the lyrics; Is money referenced? If so, how; Is there a message of uplift or unity?; What does the artist speak out against?; What lifestyles and habits are promoted?; What guidance is provided?; What problems are mentioned? and What solutions are offered? In my thesis, I explored Jay-Z and J. -

The Hilltop 10-13-2000

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 The iH lltop Digital Archive 10-13-2000 The iH lltop 10-13-2000 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 10-13-2000" (2000). The Hilltop: 2000 - 2010. 7. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • The Nation''s Largest Black Student Newspaper VOLUME 84, NO. 7 Friday, October 13, 2000 http://hilltop.howard.edu Farrakhan Library, iLab Pushes for Stronger Slated to Open Families 24 Hours Sunday By CHRISTOPHER WINDHAM By IRA PORTER rations to open the lab and library on Campus Editor Managnig Editor the new schedule, i'!immons said the need to protest had been averted. Nation of Islam leader Minster The iLab and Undergraduate "I think President Swygert and I Louis Farrakhan, said the black fam Library will begin operating on a 24 share the same vision, and that is to ily "is- in a deep crisis on all fronts," hour schedule Sunday, University have 24 hour library and computer in his officials announced earlier this week. facilities," he said. "I don't think any address President H. Patrick Swygert one is losnig. I think everyone wins." Wednes approved a pilot program earlier this The task force will use the next day to stu- week to open the facilities around the two months to gauge the frequency 1 dents and clock for the remainder of the semes of student usage of the facilities, commu ter, Interim Associate Provost Dr. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption.