Nesting of the Snow Bunting on Baffin Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

FACT SHEET Arctic National Wildlife Refuge ARCTIC BIRDS IN YOUR STATE The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is a place unlike any Alabama - Ruby-crowned Kinglet Alaska - Redpoll other in the world. The Alaskan refuge, often referred to Arizona - Fox Sparrow as “America’s Serengeti,” is a remote sanctuary for diverse Arkansas - Mallard California - Snow Goose populations of migratory birds, fish, mammals, and marine Colorado - Bohemian Waxwing Connecticut - Greater Scaup life. The Refuge spans an area roughly the size of South Delaware - Black-bellied Plover Carolina and boasts snow-capped mountains, arctic tundra, Florida - Peregrine Falcon Georgia - Gray-checked Thrush foothills, wetlands, boreal forest, and fragile coastal plains. Hawaii - Wandering Tattler America’s Arctic Refuge was set aside as a safe haven for Idaho - Short-eared Owl Illinois - Northern Flicker wildlife in 1960, and it has remained wild in its more than Indiana - Dark-eyed Junco 50 years as a Refuge. Iowa - Sharp-shinned Hawk Kansas - Smith’s Longspur Kentucky – Merlin AMERICA’S LAST GREAT WILDERNESS Louisiana - Long-billed Dowitcher Maine - Least Sandpiper Maryland - Tundra Swan The Arctic Refuge is often mischaracterized as a blank, frozen void Massachusetts - Golden Plover of uninhabited tundra. Although winter frequently coats the Arc- Michigan - Long-tail Duck tic with snow and freezes the ground, it gives way to lush, vibrant Minnesota - Snowy Owl Mississippi – Northern Waterthrush growth in warmer months. In fact, the Refuge’s unparalleled diver- Missouri - American Pipit sity makes it the most biologically productive habitat in the North. Montana - Golden Eagle Nebraska - Wilson’s Warbler Landscape Nevada - Green-winged Teal The majestic Brooks Range rises 9,000 feet, providing sharp contrast New Hampshire - Dunlin New Jersey – Canvasback to the flat, wetlands-rich coastal plains at its feet. -

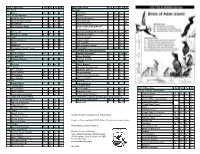

Birds of Anchorage Checklist

ACCIDENTAL, CASUAL, UNSUBSTANTIATED KEY THRUSHES J F M A M J J A S O N D n Casual: Occasionally seen, but not every year Northern Wheatear N n Accidental: Only one or two ever seen here Townsend’s Solitaire N X Unsubstantiated: no photographic or sample evidence to support sighting Gray-cheeked Thrush N W Listed on the Audubon Alaska WatchList of declining or threatened species Birds of Swainson’s Thrush N Hermit Thrush N Spring: March 16–May 31, Summer: June 1–July 31, American Robin N Fall: August 1–November 30, Winter: December 1–March 15 Anchorage, Alaska Varied Thrush N W STARLINGS SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER SPECIES SPECIES SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER European Starling N CHECKLIST Ross's Goose Vaux's Swift PIPITS Emperor Goose W Anna's Hummingbird The Anchorage area offers a surprising American Pipit N Cinnamon Teal Costa's Hummingbird Tufted Duck Red-breasted Sapsucker WAXWINGS diversity of habitat from tidal mudflats along Steller's Eider W Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Bohemian Waxwing N Common Eider W Willow Flycatcher the coast to alpine habitat in the Chugach BUNTINGS Ruddy Duck Least Flycatcher John Schoen Lapland Longspur Pied-billed Grebe Hammond's Flycatcher Mountains bordering the city. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel Eastern Kingbird BOHEMIAN WAXWING Snow Bunting N Leach's Storm-Petrel Western Kingbird WARBLERS Pelagic Cormorant Brown Shrike Red-faced Cormorant W Cassin's Vireo Northern Waterthrush N For more information on Alaska bird festivals Orange-crowned Warbler N Great Egret Warbling Vireo Swainson's Hawk Red-eyed Vireo and birding maps for Anchorage, Fairbanks, Yellow Warbler N American Coot Purple Martin and Kodiak, contact Audubon Alaska at Blackpoll Warbler N W Sora Pacific Wren www.AudubonAlaska.org or 907-276-7034. -

Snow Bunting (Plectrophenax Nivalis) Vulnerability: Presumed Stable Confidence: Moderate

Snow Bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) Vulnerability: Presumed Stable Confidence: Moderate The Snow Bunting is one of the first birds to return to their Arctic breeding grounds, with males arriving in early April. This species occurs throughout the circumpolar arctic and, as a cavity- nester, will use human-made nest sites (e.g. barrels, buildings, pipelines) as readily as natural ones (rock cavities, under boulders, cliff faces; Lyon and Montgomerie 1995). Snow Buntings consume a wide variety of both plant (e.g. seeds, plant buds) and animal prey (invertebrates). Their wintering range is centered in the northern continental US and southern Canada although it extends north into the low arctic in some places (Lyon and Montgomerie 1995). Current global population estimate is 40 million (Rich et al. 2004). Arctic Alaska (see Martin et al. 2009) is not likely to have a strong negative or positive affect on this species. Current projections of annual potential evapotranspiration suggest negligible atmospheric-driven drying for the foreseeable future (TWS and SNAP). Thus atmospheric moisture, as an exposure factor, was not heavily weighted in the assessment. A. Leist Range: We used the extant NatureServe range map for the CCVI as it matched the Birds of North America and other range descriptions (Johnson and Herter 1989). Human Response to CC: Increased human activity and infrastructure associated with human response to climate change could benefit Snow Buntings by providing increased artificial nesting habitat, as they are known to readily take advantage of human infrastructure (Lyon and Montgomerie 1995, J. Liebezeit, pers. obs.). Because it is unlikely that there will be significant development of this type in Arctic Alaska, the influence on this species would be Dietary Versatility: The Snow Bunting’s varied nominal. -

Illinois Birds: Volume 4 – Sparrows, Weaver Finches and Longspurs © 2013, Edges, Fence Rows, Thickets and Grain Fields

ILLINOIS BIRDS : Volume 4 SPARROWS, WEAVER FINCHES and LONGSPURS male Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder female Photo © John Cassady Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Mary Kay Rubey Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder American tree sparrow chipping sparrow field sparrow vesper sparrow eastern towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus Spizella arborea Spizella passerina Spizella pusilla Pooecetes gramineus Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder lark sparrow savannah sparrow grasshopper sparrow Henslow’s sparrow fox sparrow song sparrow Chondestes grammacus Passerculus sandwichensis Ammodramus savannarum Ammodramus henslowii Passerella iliaca Melospiza melodia Photo © Brian Tang Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Lincoln’s sparrow swamp sparrow white-throated sparrow white-crowned sparrow dark-eyed junco Le Conte’s sparrow Melospiza lincolnii Melospiza georgiana Zonotrichia albicollis Zonotrichia leucophrys Junco hyemalis Ammodramus leconteii Photo © Brian Tang winter Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder summer Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Mark Bowman winter Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder summer Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Nelson’s sparrow -

(2007): Birds of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska Please

Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi OSPREYS FINCHES Osprey Ca Ca Ac Brambling I Ca Ca EAGLES and HAWKS Hawfinch I Ca Northern Harrier I I I Common Rosefinch Ca Eurasian Sparrowhawk Ac (Ac) Pine Grosbeak Ca Bald Eagle* C C C C Asian Rosy-Finch Ac Rough-legged Hawk Ac Ca Ca Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch* C C C C OWLS (griseonucha) Snowy Owl I Ca I I Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (littoralis) Ac Short-eared Owl* R R R U Oriental Greenfinch Ca FALCONS Common Redpoll I Ca I I Eurasian Kestrel Ac Ac Hoary Redpoll Ca Ac Ca Ca Merlin Ca I Red Crossbill Ac Gyrfalcon* R R R R White-winged Crossbill Ac Peregrine Falcon* (pealei) U U C U Pine Siskin I Ac I SHRIKES LONGSPURS and SNOW BUNTINGS Northern Shrike Ca Ca Ca Lapland Longspur* Ac-C C C-Ac Ac CROWS and JAYS Snow Bunting* C C C C Common Raven* C C C C McKay's Bunting Ca Ac LARKS EMBERIZIDS Sky Lark Ca Ac Rustic Bunting Ca Ca SWALLOWS American Tree Sparrow Ac Tree Swallow Ca Ca Ac Savannah Sparrow Ca Ca Ca Bank Swallow Ac Ca Ca Song Sparrow* C C C C Cliff Swallow Ca Golden-crowned Sparrow Ac Ac Barn Swallow Ca Dark-eyed Junco Ac WRENS BLACKBIRDS Pacific Wren* C C C U Rusty Blackbird Ac LEAF WARBLERS WOOD-WARBLERS Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Wood Warbler Ac Yellow Warbler Ac Dusky Warbler Ac Blackpoll Warbler Ac DUCKS, GEESE and SWANS Kamchatka Leaf Warbler Ac Yellow-rumped Warbler Ac Emperor Goose C-I Ca I-C C OLD WORLD FLYCATCHERS "HYPOTHETICAL" species needing more documentation Snow Goose Ac Ac Gray-streaked Flycatcher Ca American Golden-plover (Ac) Greater White-fronted Goose I -

The Status and Occurrence of Mckay's Bunting (Plectrophenax

The Status and Occurrence of McKay’s Bunting (Plectrophenax hyperboreus) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin. Introduction and Distribution The McKay’s Bunting (Plectrophenax hyperboreus) is one of North America’s rarest passerine species. The entire breeding population of McKay’s Buntings is found on the isolated islands of St. Matthew and Hall Islands in the middle of the Bering Sea (Roberson 1980, Winker et al. 2002). A survey conducted in 2003 found that the world population is now known to be over 30,000 birds. (Rogers 2005). McKay’s Buntings have been found in the summer months on other Bering Sea islands, such as St. Paul, St. George, King and St. Lawrence Islands, but they are, by no means, annually occurring at these locations (Rogers 2005, West 2008). When they have been found in these other locations there are often no more than a handful of McKay’s Buntings in a given summer, and the birds that are located are almost always males (Rogers 2005). There have been some documented cases of McKay’s Buntings found on both St. Paul and St. Lawrence Island breeding with Snow Buntings (Sealy 1969, West 2008). As a result hybrid birds have been found in some years (Sealy 1969, West 2008). This has led some authorities to question if the McKay’s Bunting is in fact a subspecies of the Snow Bunting (Sealy 1969, Rogers 2005). For now the AOU still has the two species separated, but they are considered closely related to each other (Chesser 2013). Recent DNA research has helped show that McKay’s Buntings, though a close relative to the Snow Bunting, is, in fact genetically different enough to Snow Bunting that McKay’s Bunting should remain its own species (Maley 2004). -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Nine More Snow Bunting Returns-W.--In Bird-Ba•Zdb•G,Vc,1

Vol.1932HI GeneralNotes [175 been taken in modern literature of an eveu earlier record than that men- tioned m Mr. Fogg's article. ']'here is iu my possessiona copy of "British ZoOlogy. / Vol. II. / Class II. Division II. / Water-Fowl. / with an / appendix./ Warrington / Printed by William Eyres, / for / Benjamin White, at Horace's Head, Fleet Street, London. / MDCCLXXVI." This is part of Pennant's British ZoOlogy. On page 356 in speaking of the Common Heron, the author says: "h is said to be very long lived; by Mr. Keysler's account, it may exceed sixty- years•; and by a recent in- stance of one that was taken in Holland by a hawk belonging to the Stadtholder, its longevity is again confirmed, the bird having a silver plate fastened to one leg, with an inscription,importing it had beenbefore struck by the elector of Cologne's hawks in 1735." Not being able to find a copy of Keyslet's Travels in the Milwaukee Library in order to investigate this citation, I asked Mr. Charles L. Whittle to consultthe work, whichhe couldprobably find in somelibrary in New England. This he succeededin doing, and the following reference from the work in questiongives the details of the heron-bandingcited bv Pennant,as sent me by Mr. Whittle: 'In this palace2 the court often d)vertsitself with huntingthe heron,and every 3'ear, at the conclusion of it, a heron, whose good fortune it has been to be taken alive, is, for memorial, set at liberty with a silver ring on its foot, on xvhichthe name of the reigningelector is engraven.Xo longerago than last spring,one of thesebirds was takena secondtime, havingon its ring the nameof duke Ferdinand,grandfather to the presentelector, so that it has survivedits former adventureabove sixty years: they put a ring with the present elector'sname upon its leg, and gave it its liberty again.'From Vol. -

2008 Annual Report of Research and Monitoring in Torngat Mountains National Park

Annual Report of Research and Monitoring In Torngat Mountains National Park 2008 2 2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF RESEARCH AND MONITORING IN TORNGAT MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK Many people contributed to this report. We wish to acknowledge them for their commitment to the project, and their timely submission of reports. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Information about Parks Canada research and monitoring activities in Torngat Mountains National Park was provided by Parks Canada staff: Dr. Dave Cote, Dr. Jenneth Curtis, Dr. Tom Knight, Craig Burden, Scott Taylor, Alain Boudreau, Paul Dixon, Darroch Whitaker and Angus Simpson. Reports on ArcticNet research were provided by: Dr. Trevor Bell and Dr. Sam Bentley of Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador; Sebastian Luque, Jackie Bastick, Tanya Brown and Tom Sheldon of Environmental Sciences Group Royal Military College; and Reinhard Pienitz of Laval University. International Polar Year Research reports were provided by: Dr. Luise Hermanutz, Dr. Paul Marino, Dr. John D. Jacobs, Dr. Alvin Simms, Sarah Chan, Brittany Cranston, Julia Wheeler, Dan Myers, Michael Upshall, Peter Kncz of Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador; Dr. Chantal Ouimet Parks Canada; Dr. Joseph Culp, Dr. Allen Curry, Andrea Chute and Allison Ritcey of University of New Brunswick; J. Brian Dempson Fisheries and Oceans, Atlantic Region; Dr. Donald McLennan of Parks Canada Agency Ottawa; and Yu Zhang and Junhua Li from the Canadian Centre for Remote Sensing in Ottawa. We would also like to extend a special thanks to the Student Interns who provided valuable assistance to many of the research projects described in this document. They are Dorothy Angnatok, Elias Obed, Sheena Merkuratsuk, Anita Fells and Minnie OkKuatsiak all from Nain Nunatsiavut. -

UGRD 2013 Spring Rach David

Morphological characteristics follow the mtDNA sequence of evolutionary descent within the family Calcariidae. By David Rach with Eric C. Atkinson So what is a Calcariidae??? Calcariidae • Family of sexually dimorphic, sparrow-like passerines that inhabit shrub steppe habitats of North America Calcariidae • Family of sexually dimorphic, sparrow-like passerines that inhabit shrub steppe habitats of North America • Arose 4.2-6.5 mya during a Miocene period of accelerated drying and cooling. • 6 Species, 4 of which are found in Wyoming In Wyoming during the Summer Chestnut-collared Longspur (Calcarius ornatus) CCLO McCown’s Longspur (Rynchophanes mccownii) MCLO In Wyoming during the Winter Snow Bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) SNBU Lapland Longspur (Calcarius lapponicus) LALO Not found in Wyoming Smith’s Longspur (Calcarius pictus) SMLO McKay’s Bunting Plectrophenax hyperboreus MKBU McCown’s Longspur Female Male Previously Believed Calcariidae Longspurs Buntings CCLO SMLO MCLO LALO SNBU MKBU Currently Believed Calcariidae Calcarius Rynchophanes Plectrophenax CCLO SMLO LALO MCLO SNBU MKBU Purpose of Study: • Avian Taxonomy • Does the Morphology follow the DNA? • Trait that distinguishes between the two sub-clades? Identifying and Cataloging Museum Specimens Methods Measurements • Wing Chord (natural) • Tail Length • Tarsus (Leg) Length • Hallux (Toe Nail) Length Measurements • Exposed Culmen • Bill Length • Bill Depth • Bill Width Statistics: • Principal Component Analysis (PCA) • Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) • Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering -

Bird Check List Master 5-3-18

Wrens (TROGLODYTIDAE) Black-throated Blue Warbler 4 Red-winged Blackbird 4 Carolina Wren 6, 7 Yellow-rumped Warbler 4 Ο Eastern Meadowlark House Wren 4 Pine Warbler 4 Common Grackle 4 Ο Sedge Wren Ο Prairie Warbler Brown-headed Cowbird 4 Ο Bobolink 4 Ο Marsh Wren Palm Warbler Bay-breasted Warbler 3 Baltimore Oriole 4 Gnatcatchers (POLIOPTILIDAE) Ο Cerulean Warbler Ο Orchard Oriole Blue-gray Gnatcatcher 4 Black & White Warbler 4 Finches & Allies (FRINGILLIDAE) Kinglets (REGULIDAE) Ο Prothonotary Warbler Purple Finch 7 Golden-crowned Kinglet 3, 5 Blackburnian Warbler 4 House Finch 7 Ruby-crowned Kinglet 3, 5 Ο Kentucky Warbler American Goldfinch 7 Thrushes & Allies (TURDIDAE) Ο Sawainson’s Warbler Ο Red Crossbill Hermit Thrush 4 Ο Connecticut Warbler Ο Common Redpoll B Wood Thrush 4 L Mourning Warbler 4 Pine Siskin 1, 5 Swainson’s Thrush 5 Canada Warbler 4, 6 Ο Pine Grosbeak American Robin 7 Common Yellowthroat 4 Ο Evening Grosbeak Veery 4 Ο Northern Parula Old World Sparrows (PASSERIDAE) Eastern Bluebird 4 American Redstart 4 House Sparrow 7 i i Mockingbirds & Thrashers (MIMIDAE) Ovenbird 4 Not Listed Gray Catbird 4 Ο Northern Waterthrush _________________________ Northern Mockingbird 4 Ο Louisiana Waterthrush (indicates family classification) The species noted with a square were compiled from actual Brown Thrasher 4 New World Buntings & Sparrows (PASSERELLIDAE) sightings within the Genesee County Park & Forest by the Starlings (STURNIDAEL) American Tree Sparrow 1 following sources: i. Individual birders reporting their findings on E-Bird since 2010. r Chipping Sparrow 4 s European Starling 7 Field Sparrow 4 ii. Buffalo Ornithological Society one day bird census findings each Wagtails & Pipits (MOTACILLIDAE) April, May & October since 2011. -

Terrestrial Ecozones of Canada

Terrestrial Ecozones of Canada Ecological land classification is a process of delineating and classifying ecologically distinctive areas and classification areas of the earth's surface. Each area can be viewed as a discrete system which has resulted from interplay of geologic, landform, soil, vegetation, climatic, water and human factors which may be present. Canada is divided into 15 separate terrestrial ecozones. Ecozones are areas of the earth's surface representative of large and very generalized ecological units characterized by interactive and adjusting abiotic and biotic factors. Canada's national parks and national park reserves are currently represented in 14 of the 15 terrestrial ecozones. 1. Arctic Cordillera 2. Northern Arctic 3. Southern Arctic 4. Atlantic Maritime 5. Boreal Cordillera 6. Boreal Plains 7. Boreal Shield 8. Hudson Plains 9. Prairie 10. Mixedwood Plains 11. Montane Cordillera 12. Pacific Maritime 13. Taiga Cordillera 14. Taiga Plains 15. Taiga Shield Reference: Lands Directorate, Terrestrial Ecozones Of Canada, Ecological Land Classification No. 19, 1986, p. 26. Arctic Cordillera Ecozone The Arctic Cordillera contains the only major mountainous environment other than the Rocky Mountain system. It occupies eastern Baffin and Devon islands and most of Ellesmere and Bylot islands. The highest parts are strikingly crowned by ice caps and multiple glaciers. The climate is very cold and arid. Mean daily January temperatures range from -25.5ºC in the south to -35ºC in the north and mean daily July temperatures are about 5ºC. Precipitation amounts to 200 mm to 300 mm generally with higher totals on exposed eastern slopes and at lower latitudes. Vegetation at upper elevations is largely absent due to the permanent ice and snow.