Smokeless Tobacco and Kids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altria.Com/Proxy

6601 West Broad Street Richmond, Virginia 23230 Dear Fellow Shareholder: It is my pleasure to invite you to join us at the 2016 Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Altria Group, Inc. to be held on Thursday, May 19, 2016 at 9:00 a.m., Eastern Time, at the Greater Richmond Convention Center, 403 North 3rd Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219. At this year’s meeting, we will vote on the election of 11 directors, the ratification of the selection of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP as the Company’s independent registered public accounting firm and, if properly presented, two shareholder proposals. We will also conduct a non-binding advisory vote to approve the compensation of the Company’s named executive officers. There also will be a report on the Company’s business, and shareholders will have an opportunity to ask questions. To attend the meeting, an admission ticket and government-issued photo identification are required. To request an admission ticket, please follow the instructions on page 9 in response to Question 16. One immediate family member who is 21 years of age or older may accompany a shareholder as a guest. We use the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule that allows companies to furnish proxy materials to their shareholders over the Internet. We believe this expedites shareholders receiving proxy materials, lowers costs and conserves natural resources. We thus are mailing to many shareholders a Notice of Internet Availability of Proxy Materials, rather than a paper copy of the Proxy Statement and our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2015. -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company | Inc. Altria Group, Report 2020 Annual an Altria Company From tobacco company To tobacco harm reduction company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. | 6601 W. Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23230-1723 | altria.com 2020 Annual Report Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Dear Fellow Shareholders March 11, 2021 Altria delivered outstanding results in 2020 and made steady progress toward our 10-Year Vision (Vision) despite the many challenges we faced. Our tobacco businesses were resilient and our employees rose to the challenge together to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, political and social unrest, and an uncertain economic outlook. Altria’s full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) grew 3.6% driven primarily by strong performance of our tobacco businesses, and we increased our dividend for the 55th time in 51 years. Moving Beyond Smoking: Progress Toward Our 10-Year Vision Building on our long history of industry leadership, our Vision is to responsibly lead the transition of adult smokers to a non-combustible future. Altria is Moving Beyond Smoking and leading the way by taking actions to transition millions to potentially less harmful choices — a substantial opportunity for adult tobacco consumers 21+, Altria’s businesses, and society. To achieve our Vision, we are building a deep understanding of evolving adult tobacco consumer preferences, expanding awareness and availability of our non-combustible portfolio, and, when authorized by FDA, educating adult smokers about the benefits of switching to alternative products. -

Grizzly Gridder Ursinus College Official Football Program, November 7, 1936 Varsity Club Ursinus College

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Ursinus College Football Programs Football 11-7-1936 Grizzly Gridder Ursinus College Official Football Program, November 7, 1936 Varsity Club Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/football_programs Part of the Social History Commons, Sports Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Club, Varsity, "Grizzly Gridder Ursinus College Official Football Program, November 7, 1936" (1936). Ursinus College Football Programs. 21. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/football_programs/21 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Football at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ursinus College Football Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRIZZLY GRIDDER vs November 7, 1936 Price 25c .. URSINUS COLLEGE The Oldest College in Montgomery County The Only Co-educational College in Montgomery County • N. E. McCLURE, Ph. D., Litt. D. President GRIZZLY GRIDDER OffICIAL FOOTBALL PROGRAM FOR ALL HOME GAMES OF U RSINUS COLLEGE Published by VARSITY CLUB LJRS INUS COLLEGE COLLEGEVILLE. PA. Vol. 4. No.2 November 7. 1936 25 cents P. E. Reynold s. '37. Editor J. D. Mertz. Assistfll/t Editm' A. E. Lipkin. Bllsil/ess ""tll/flger McAVOY WAS RIGHT '1\\0 1I1 01lth, ago Coach 1\l e l\ vo) pred ic ted III a ll the cOllferenee gallI I" L r,illll s has " \\ 1" 11 pili Ollt a team we can be proud or' engaged in so far the Grizzlies hal e taken and he IHIS ri ghi, becausc we havc. -

CONTINUED NEW CATEGORY ACCELERATION Trading Update - Ahead of Closed Period Commencing 28 June 2021

8 June 2021 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO p.l.c. 2021 First Half Pre-Close Trading Update CONTINUED NEW CATEGORY ACCELERATION Trading update - ahead of closed period commencing 28 June 2021 Jack Bowles, Chief Executive: ‘We are accelerating our transformation to build A Better Tomorrow. We are creating brands of the future and sustainable value for all our stakeholders. We added +1.4m non-combustible product consumers1 in Q1, to reach a total of 14.9m. We are investing and building strong, fast growing international brands in each segment, rapidly accelerating our reach and consumer acquisition, thanks to our digitalisation and our multi-category consumer-centric approach, supported by the right resources and products, and our agile organisation. Our portfolio of non-combustible products is tailored to meet the needs of adult consumers. We are growing New Categories at pace, encouraging more smokers to switch to scientifically substantiated reduced risk alternatives2. We continue to expect 2021 to be a pivotal year for the business, with accelerating New Category revenue growth, a clear pathway to New Category profitability by 2025, and leverage reducing to c.3x by year end. ESG is deeply embedded in our organisation, and we have set ourselves stretching targets: £5bn New Category revenue by 2025; 50 million consumers of non-combustible products and carbon neutrality across our own operations by 20303, which I am confident in delivering. In summary, we are accelerating our transformation with increased investment capitalising on our growing momentum in the New Categories, and a record quarter for consumer acquisition. This, together with our strong business performance, is reflected in our upgraded Group revenue growth guidance of above 5% for 2021. -

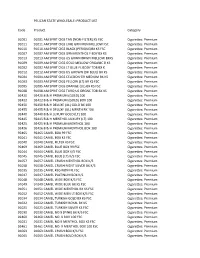

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Member List Version

APPENDIX K: SURVEY (MEMBER LIST VERSION) |___|___|___|___| |___| |___|___| |___|___|___|___| |___|___|___|___| Year Interview Interviewer Survey Number Respondent ID Supervisor Alaska Native Adult Tobacco Survey Member List Version TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 2 2. General Health .......................................................................................... 5 3. Cigarette Use ............................................................................................ 5 4. Iqmik Use ............................................................................................... 14 5. Chewing Tobacco (Spit) .......................................................................... 23 6. Snuff or Dip Tobacco .............................................................................. 32 7. Secondhand Smoke Exposure ................................................................. 42 8. Risk Perception ...................................................................................... 44 9. Demographics......................................................................................... 48 10. User-Selected Items ............................................................................. 52 Public burden of this collection of information is estimated to average 40 minutes per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, -

Alameda County Tobacco Retailer License & Flavored Tobacco Training

ALAMEDA COUNTY TOBACCO RETAILER LICENSE & FLAVORED TOBACCO PRESENTATION 7/29/20 Providing Education and Support to Tobacco Retailers in Alameda County Agenda ❑ Welcome/Introductions ❑ Zoom Housekeeping ❑ Why Tobacco Retail Regulations? ❑ Alameda County’s Tobacco Retail Licensing Ordinance ❑ Restricted Tobacco Products ❑ Questionable Products ❑ Tobacco Retailer License Application Process ❑ Q & A WHY TOBACCO RETAIL REGULATIONS? Flavored Tobacco Hooks Kids Over 90% of adult smokers started before age 18 Flavored tobacco initiates youth tobacco use 4 out of 5 youth smokers started with a flavored product Adolescents are more likely than adults to use flavored e-cigs Fruit and candy flavors are designed to appeal to youth users by masking the harsh taste of tobacco Strong Tobacco Retail Licensing ordinances are effective at decreasing youth tobacco sales rates ALAMEDA COUNTY’S TOBACCO RETAILER LICENSING (TRL) ORDINANCE Overview of Adopted TRL Ordinance Purpose is to reduce youth access to tobacco, and to limit negative public health effects of tobacco use. Requires businesses in Unincorporated Alameda County that sell tobacco to obtain a local license annually to sell tobacco. Provides enforcement mechanism; holds retailers accountable to comply with local requirements, as well as state and federal tobacco laws. Overview of Adopted TRL Ordinance TRL ordinance adopted by BOS on January 14, 2020 Electronic Smoking Devices adopted by BOS on March 10, 2020 Retailers obtain TRL by August 7, 2020 Enforcement of both laws begin: September -

Tobacco in Canada Addressing Knowledge Gaps Important to Tobacco Regulation Environmental Scan – Autumn 2020

Tobacco in Canada Addressing Knowledge Gaps Important to Tobacco Regulation Environmental Scan – Autumn 2020 Vuse flagship store opens in Toronto, October 2019. December 31, 2020 Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada 134 Caroline Avenue Ottawa Ontario K1Y 0S9 www.smoke-free.ca psc @ smoke-free.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 I. Federal Government Activities .......................................................................................................................... 3 a) Policy and Regulation.................................................................................................................................... 3 B) Financial Policy ............................................................................................................................................. 5 II. Monitoring and Surveillance ............................................................................................................................. 7 III. Provincial Government activities ..................................................................................................................... 8 New Brunswick ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Newfoundland ................................................................................................................................................. -

At Work in the World

Perspectives in Medical Humanities At Work in the World Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health Edited by Paul D. Blanc, MD and Brian Dolan, PhD Page Intentionally Left Blank At Work in the World Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health Perspectives in Medical Humanities Perspectives in Medical Humanities publishes scholarship produced or reviewed under the auspices of the University of California Medical Humanities Consortium, a multi-campus collaborative of faculty, students and trainees in the humanities, medi- cine, and health sciences. Our series invites scholars from the humanities and health care professions to share narratives and analysis on health, healing, and the contexts of our beliefs and practices that impact biomedical inquiry. General Editor Brian Dolan, PhD, Professor of Social Medicine and Medical Humanities, University of California, San Francisco (ucsf) Recent Monograph Titles Health Citizenship: Essays in Social Medicine and Biomedical Politics By Dorothy Porter (Fall 2011) Paths to Innovation: Discovering Recombinant DNA, Oncogenes and Prions, In One Medical School, Over One Decade By Henry Bourne (Fall 2011) The Remarkables: Endocrine Abnormalities in Art By Carol Clark and Orlo Clark (Winter 2011) Clowns and Jokers Can Heal Us: Comedy and Medicine By Albert Howard Carter iii (Winter 2011) www.medicalhumanities.ucsf.edu [email protected] This series is made possible by the generous support of the Dean of the School of Medicine at ucsf, the Center for Humanities and Health Sciences at ucsf, and a Multi-Campus Research Program grant from the University of California Office of the President. -

Step-Changing New Categories: the New

Investor Day | 14 March 2019 Oral Category | The new opportunity Vincent Duhem Category Director Important Information The information contained in this presentation in relation to British American Tobacco p.l.c. (“BAT”) and its subsidiaries has been prepared solely for use at this presentation. The presentation is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity that is a citizen or resident or located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would require any registration or licensing within such jurisdiction. References in this presentation to ‘British American Tobacco’, ‘BAT’, ‘Group’, ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ when denoting opinion refer to British American Tobacco p.l.c. and when denoting tobacco business activity refer to British American Tobacco Group operating companies, collectively or individually as the case may be. The information contained in this presentation does not purport to be comprehensive and has not been independently verified. Certain industry and market data contained in this presentation has come from third party sources. Third party publications, studies and surveys generally state that the data contained therein have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but that there is no guarantee of accuracy or completeness of such data. Forward-looking Statements This presentation does not constitute an invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any BAT shares or other securities. This presentation contains certain forward-looking statements, made within the meaning of Section 21E of the United States Securities Exchange Act of 1934, regarding our intentions, beliefs or current expectations concerning, amongst other things, our results of operations, financial condition, liquidity, prospects, growth, strategies and the economic and business circumstances occurring from time to time in the countries and markets in which the Group operates. -

Smokeless Tobacco: Defective Marketing Creates a New Toxic Tort

Tulsa Law Review Volume 21 Issue 3 Spring 1986 Smokeless Tobacco: Defective Marketing Creates a New Toxic Tort Michael F. McNamara Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael F. McNamara, Smokeless Tobacco: Defective Marketing Creates a New Toxic Tort, 21 Tulsa L. J. 499 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol21/iss3/4 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McNamara: Smokeless Tobacco: Defective Marketing Creates a New Toxic Tort NOTES AND COMMENTS SMOKELESS TOBACCO: DEFECTIVE MARKETING CREATES A NEW TOXIC TORT Warning: Use of snuff can be addictive and can cause mouth cancer and other mouth disorders' I. INTRODUCTION Smokeless tobacco2 (smokeless) appears destined to join the ranks of the Ford Pinto, MER/29, DES, the Dalkon shield, and asbestos in legal history. In cases involving each of those products a proverbial smoking gun was disgorged from the defendants' files. Smokeless will undoubt- edly produce similar stonewalling and then damning revelations. An- other similarity with those products exists in that the smokeless problem is surprisingly widespread. As one state official has described it, "[t]here is a chemical time bomb ticking in the mouths of hundreds of thousands of boys in this country." 3 1. Mandatory warning label on smokeless tobacco products sold in Massachusetts, the first state to require such a label. -

Reynolds American Names New Chief Executives for Its Conwood and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company Subsidiaries

Reynolds American Inc. P.O. Box 2990 Winston-Salem, NC 27102-2990 Reynolds American names new chief executives for its Conwood and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company subsidiaries WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – Dec. 9, 2008 -- Reynolds American Inc. (NYSE: RAI) today announced the appointment of new chief executive officers for the company’s Conwood Company, LLC and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company, Inc. subsidiaries. The current chief executives of those two subsidiaries plan to retire in 2009. Bryan K. Stockdale, 50, has been named president and CEO of Conwood, the nation’s second-largest smokeless tobacco manufacturer, effective Feb. 1, 2009. Stockdale will succeed William M. Rosson, 60, who plans to retire after 34 years of service at Conwood. Stockdale is currently senior vice president of marketing operations for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Reynolds American’s largest subsidiary, and has worked for that company for 30 years. Rosson will remain with Conwood in an advisory role for a period of time after Stockdale joins the company to ensure a smooth transition. Nicholas A. Bumbacco, 44, has been named president and CEO of Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Co., effective March 1, 2009. Bumbacco will replace Richard M. Sanders, 55, who plans to remain in an advisory transition position before retiring with 32 years of service on July 1, 2009. Bumbacco is currently president and CEO of RAI’s R.J. Reynolds Global Products, Inc. subsidiary. Bumbacco has 20 years of experience in the global tobacco industry. RAI will be transitioning the lines of business formerly managed by R.J. Reynolds Global Products to other RAI subsidiaries, so no successor to Bumbacco in his previous position will be named.