Gender Relations and Inheritance in Njeguši

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montenegro Old and New: History, Politics, Culture, and the People

60 ZuZana Poláčková; Pieter van Duin Montenegro Old and New: History, Politics, Culture, and the People The authors are focusing on how Montenegro today is coming to terms with the task of becoming a modern European nation, which implies recognition not only of democracy, the rule of law, and so forth, but also of a degree of ‘multiculturalism’, that is recognition of the existence of cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities in a society that is dominated by a Slavic Orthodox majority. In his context they are analyzing the history of the struggle of the Montenegrin people against a host of foreign invaders – after they had ceased to be invaders themselves – and especially their apparently consistent refusal to accept Ottoman sovereignty over their homeland seemed to make them the most remarkable freedom fighters imaginable and led to the creation of a special Montenegrin image in Europe. This im- age of heroic stubbornness and unique martial bravery was even consciously cultivated in Western and Central Europe from the early nineteenth century onwards, as the Greeks, the Serbs, the Montenegrins and other Balkan peoples began to resist the Ottoman Empire in a more effective way and the force of Romantic nationalism began to influence the whole of Europe, from German historians to British politi- cians, and also including Montenegrin and Serbian poets themselves. And what about the present situa- tion? The authors of this essay carried out an improvised piece of investigation into current conditions, attitudes, and feelings on both the Albanian and the Slavic-Montenegrin side (in September 2012). key words: Montenegro; history; multiculturalism; identity; nationalism; Muslim; Orthodox Montenegro (Crna Gora, Tsrna Gora, Tsernagora) is a small country in the Western Balkans region with some 625,000 inhabitants,1 which became an independent nation in 2006 and a can- didate-member of the EU in 2010. -

Practical Information

EXPANDING BROADBAND ACCESS AND ADOPTION 28th–29th September 2015 Hotel Maestral, Przno/Budva, Montenegro PRACTICAL INFORMATION 1. Montenegro Montenegro is a small, but extremely attractive Mediterranean country. It is located in the south of Europe, on the Adriatic coast. Montenegro is located between 41º 52´- 43º 42´ north latitude and 18º26´ - 20º22´ east longitudes and belongs to the central Mediterranean that is Southern Europe. To the north it borders Serbia, to the southeast Kosovo and Albania, to the south it is separated from Italy by the Adriatic Sea and to the west it borders Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has about 620,000 inhabitants and an area of 13,812 km2. Montenegro is characterized by the diversity of outstanding natural beauty in a small space. To the north, there are mountain peaks with 2,524 meters above sea level and more than 100 glacial lakes. In the region there are impressive canyons of which the most famous is canyon of Tara, with depth of 1,300 m (the second in the world after Colorado). Montenegrin coastline is 293 km long and has as many as 52 km of sandy beaches which are a real tourist attraction. The coast is dominated by the medieval Mediterranean towns with fascinating architecture (Herceg Novi, Kotor, Budva, Bar, Ulcinj). Montenegro is a popular tourist destination with a number of world-recognizable sites and resorts (hotel-town Sveti Stefan, Bay of Boka Kotorska, Porto Montenegro marina). Montenegro is a multinational state that is characterized by inter-ethnic and inter-confessional harmony. Montenegrin citizens are known for their hospitality, friendliness and cordiality. -

Concerning Montenegro

WRITTEN COMMENTS OF THE EUROPEAN ROMA RIGHTS CENTRE (ERRC) AND THE CENTRE FOR ROMA INITIATIVES (“CRI”) CONCERNING MONTENEGRO FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE UNITED NATIONS COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION AT ITS 74th SESSION C E R D 7 4 t h S E S S I O N RAE IN MONTENEGRO Index 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION – LAW AND POLICY CONTEXT ............................................................ 5 3. ARTICLES 1 AND 2: PROHIBITION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION ..................................... 8 4. ARTICLE 5: EQUALITY BEFORE THE LAW .................................................................. 9 4.1 ARTICLE 5B: THE RIGHT TO SECURITY OF PERSON AND PROTECTION BY THE STATE AGAINST VIOLENCE OR BODILY HARM: VIOLENCE AGAINST RAE WOMEN .................. 9 4.2 ARTICLE 5C: POLITICAL RIGHTS AND ARTICLE 2.2: TEMPORARY SPECIAL MEASURES ................................................................................................. 10 4.3 ARTICLE 5E I: THE RIGHT TO WORK, TO FREE CHOICE OF EMPLOYMENT, TO JUST AND FAVOURABLE CONDITIONS OF WORK, TO PROTECTION AGAINST UNEMPLOYMENT, TO EQUAL PAY FOR EQUAL WORK AND TO JUST AND FAVOURABLE REMUNERATION.......... 10 4.4 ARTICLE 5E IV: THE RIGHT TO PUBLIC HEALTH, MEDICAL CARE, SOCIAL SECURITY AND SOCIAL SERVICES ................................................................................... 11 4.5 ARTICLE 5E V: THE RIGHT TO EDUCATION ....................................................... -

Montenegro Guidebook

MONTENEGRO PREFACE Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro, lies in a broad plain crossed by five rivers and surrounded by mountains, just 20 kilometers from the Albanian border. The city has a population of around 180,000 people. Bombed into rubble during World War II, Podgorica was rebuilt into a modern urban center, with high-rise apartment buildings and new office and shopping developments. While the latest Balkan war had a low impact on the physical structures, the economic sanctions had a devastating effect on employment and infrastructure. With the help of foreign investment, urban renewal is evident throughout the city, but much of it may still appear run down. Podgorica has a European-style town center with a pedestrian- only walking street (mall) and an assortment of restaurants, cafes, and boutiques. To many, its principal attraction is as a base for the exploration of Montenegro’s natural beauty, with mountains and wild countryside all around and the stunning Adriatic coastline less than an hour away. This is a mountainous region with barren moorlands and virgin forests, with fast-flowing rivers and picturesque lakes; Skadar Lake in particular is of ecological significance. The coastline is known for its sandy beaches and dramatic coves: for example, Kotor – the city that is protected by UNESCO and the wonderful Cathedral of Saint Typhoon; the unique baroque Perast; Saint George and Our Lady of the Rock islands – all locations that tell a story of a lasting civilization and the wealth of the most wonderful bay in the world. The area around the city of Kotor is a UNESCO World Heritage site for its natural beauty and historic significance. -

Gender Analysis and Recommendations For

Gender analysis and recommendations for strengthening the inclusion of gender perspective in the implementation of the Action "Improving Procedural Safeguards in Judicial Proceedings in Montenegro" Ms Sanja Elezovic This document was produced with the financial support of the European Union and the Council of Europe. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of either party. © 2019 Council of Europe. All rights reserved. Licensed to the European Union under conditions. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc.) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Directorate of Communications (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 5 Legal and Institutional Framework for Gender Equality........................................................ 7 Women and Men in Montenegro - access to and share of resources and decision making: .............................................................................................................................................. 10 Judicial framework, practice and penal policies -

Identification and Evaluation of Landscape As a Precondition for Planning Revitalization and Development of Mediterranean Rural Settlements—Case Study: Mrkovi Village, Bay of Kotor

sustainability Article Identification and Evaluation of Landscape as a Precondition for Planning Revitalization and Development of Mediterranean Rural Settlements—Case Study: Mrkovi Village, Bay of Kotor, Montenegro Željka Curovi´cˇ 1 , Mili´c Curovi´cˇ 2, Velibor Spalevi´c 3, Milorad Janic 4, Paul Sestras 5 and Svetislav G. Popovi´c 6,* 1 Ministry of Sustainable Development and Tourism, 81000 Podgorica, Montenegro; [email protected] 2 Biotechnical Faculty, University of Montenegro, 81000 Podgorica, Montenegro; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro, 81400 Niksic, Montenegro; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Forestry, University of Belgrade, Kneza Viseslava, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] 5 Department of Terrestrial Measurement and Cadastre, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, 400020 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; [email protected] 6 Faculty of Architecture, University of Montenegro, 81000 Podgorica, Montenegro * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +382-69-101-747 Received: 1 March 2019; Accepted: 30 March 2019; Published: 5 April 2019 Abstract: This paper presents a case study of the village of Mrkovi in the Bay of Kotor, Montenegro, showing the importance of landscape identification and assessment in planning the revitalization and development of Mediterranean rural settlements. The research revealed the methods of identification and evaluation of different landscape types. Moreover, it showed how such an approach could considerably contribute to the preservation of the space’s identity and quality by taking into account the existing characteristics of the space or the relationship between cultural and natural heritage. The identification of the landscape types was followed by the evaluation of individual elements and assessment of vulnerability in relation to the space’s natural, cultural, and visual quality. -

Anthropology of Gender in Montenegro. an Introduction

Comp. Southeast Europ. Stud. 2021; 69(1): 5–18 In the Name of the Daughter. Anthropology of Gender in Montenegro Čarna Brković* In the Name of the Daughter – Anthropology of Gender in Montenegro. An Introduction https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2021-2013 Gender in Montenegro In 2012 international organizations warned that Montenegro is one of the world’s leaders in sex-selective abortion, with as a result significantly fewer births of babies recognized as girls.1 Initially, that piece of data seemed to attract little attention, but that changed after a few years. NGOs working on women’srightsorganizedcampaigns advocating against the practice of sex-selective abortion; German journalists came to Montenegro and reported on them; the Montenegrin national newspaper Pobjeda stopped publishing information on the genders of new-born children and began reporting births gender-neutrally instead. In dominant media and NGO discourses, sex- selective abortion was interpreted as the result of the patriarchal backwardness of the country, where sons were more valued and, therefore, more wanted than daughters. The collection of articles in front of you explores how to look beyond the balkanist discourse to understand abortion and other gendered practices in Montenegro.2 It articulates anthropological criticism of patriarchy, misogyny, and gender inequality in Montenegro without reiterating the common tropes about 1 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) data reveal that Montenegro is one of the top eleven countries in the world for sex imbalance at birth; that is in the difference between the numbers of boys and girls. Cf. Christophe Z. Guilmoto, Sex Imbalances at Birth. Current Trends, Consequences and Policy Implications, UNFPA Asia and Pacific Regional Office, Bangkok 2012, 20. -

Montenegro & the Bay of Kotor

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 28 Travele rs JO URNEY Montenegro & the Bay of Kotor Inspiring Moments > Visit Venetian-era towns along the Bay of Kotor, a beautiful blue bay cradled between plunging emerald mountains. > Delight in Dubrovnik’s magnificent architecture, towering city walls and INCLUDED FEATURES limestone-paved Stradun. Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary > Sip Montenegrin wines and learn about – 6 nights in Tivat, Montenegro, at the Day 1 Depart gateway city Montenegro’s long tradition of viticulture at deluxe Regent Porto Montenegro. Day 2 Arrive in Dubrovnik and one of Eastern Europe’s finest vineyards. – 1 night in Dubrovnik, Croatia, at the transfer to hotel in Tivat > Discover the serene ambience of two deluxe Hilton Imperial Dubrovnik. Day 3 Cetinje enchanting Orthodox monasteries. > Revel in the remarkable ecosystem and Transfers (with baggage handling) Day 4 Perast | Kotor – Deluxe motor coach transfers during the Day 5 Lake Skadar | Tuzi unspoiled natural beauty of Lake Skadar. Land Program. Day 6 Tivat | Kotor > Step inside a restored Yugoslav submarine at the Maritime Heritage Museum. Extensive Meal Program Day 7 Budva > Uncover the proud history of – 7 breakfasts, 4 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 8 Dubrovnik Cetinje, Montenegro’s cultural center. including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 9 Transfer to Dubrovnik airport tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine and depart for gateway city > Experience two UNESCO World with dinner. Heritage sites. Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. Your One-of-a-Kind Journey Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. – Discovery excursions highlight the local Activity Level: We have rated all of our excursions with Our Lady of the Rocks culture, heritage and history. -

Pearls of Dalmatia with Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar

PEARLS OF DALMATIA WITH DUBROVNIK & THE ISLAND OF HVAR April 11-25, 2019 15 days from $4,184 total price from Boston, New York ($3,695 air & land inclusive plus $489 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumni & Friends of the Cornell Alumni Association Travel Program Dear Alumni, Parents, and Friends, We invite you to be among the thousands of Cornell alumni, parents and friends who view the Cornell Alumni Association (CAA) Travel Program as their first choice for memorable travel adventures. If you’ve traveled with CAA before, you know to expect excellent travel experiences in some of the world’s most interesting places. If our travel offerings are new to you, you’ll want to take a closer look at our upcoming tours. Working closely with some of the world’s most highly-respected travel companies, CAA trips are not only well organized, safe, and a great value, they are filled with remarkable people. This year, as we have for more than forty years, are offering itineraries in the United States and around the globe. Whether you’re ascending a sand dune by camel, strolling the cobbled streets of a ‘medieval town’, hiking a trail on a remote mountain pass, or lounging poolside on one of our luxury cruises, we guarantee ‘an extraordinary journey in great company.’ And that’s the reason so many Cornellians return, year after year, to travel with the Cornell Alumni Association. -

~Ojfi'c/ --'/ • L~.;) 0150700023

~ojfi'C/ --'/ • L~.;) 0150700023 Mr. Tim Curtis Secretary of the 2003 Convention UNESCO Section of Intangible Cultural Heritage 7, Place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris France Subject: Opposition to an independent nomination of the Bokelj Navy for the UNESCO representative list of Intangible Cultural Heritage as submitted by the Republic Montenegro Dear Sir, there is an old folk saying stating that it is the history of a people to determine its identity through future generations. We can all learn a lot from history; history is, just to quote another popular expression, "life's teacher". This saying is true above all for us Europeans and even much more for the area of the permanently turbulent Balkan Peninsula. Respecting a people's heritage on the territory of another country, even if that particular people, due to historical circumstances, is not present any more on the territory of that country or has been reduced to a small minority, is a prime scope that any modern European country should aim at if it wants to be part of modern society. The ceremony celebrating Saint Tryphon and the traditional dance named after the Saint, Saint Tryphon's Kolo, are intangible cultural heritage of the Croats living in the Bay of Kotor (Boka Kotorska), who maintained that tradition through centuries and did so particularly within the Catholic Church; settling down in the Bay of Kotor, our Orthodox sister nations, the Montenegrins and the Serbs, accepted that holy tradition of ours and passed it over from generation to generation together with us Catholic people. The Confraternity Bokelj Navy 809 has always been first and foremost a "spiritual" organization devoted to and celebrating SaintTryphon, the Patron Saint of all us Bokelj people. -

20120828 Lekic Montenegro's EU Accession, Briefing Paper

MONTENEGRO’S ACCESSION TO THE EU: TAKING STOCK AND SUGGESTING AREAS FOR PROGRESS Maša Lekić Abstract With the opening of the EU accession negotiations at the end of June 2012, Montenegro has been awarded with recognition of making progress in the past years and endorsing its political dedication to become an EU member. As a candidate state and a relatively young country at the international stage, Montenegro is particularly devoted to joining the Union. In order to fulfill the EU membership criteria, Montenegro is focusing on matching the political and economic criteria set by the EU, implementing the acquis communautaire (the EU legislation), and endorsing the EU principles of: democracy, the rule of law, respect for human rights and protection for minority groups, as well as economic criteria. Nevertheless, Montenegro is still facing obstacles in reform implementation, the most challenging being public administration reform, reforming the judicial system and strengthening the rule of law, protecting minority rights, enhancing media freedom and fighting corruption and organized crime. The Global Governance Institute has identified three major challenges obstructing Montenegro’s path to EU membership: protection of women's rights, overcoming regional differences and reforming the judicial system. GGI Briefing Paper 3/2012 GGI Briefing Paper Series The Global Governance Institute Peace & Security Section Pleinlaan 5, Brussels B-1050 Belgium © The Global Governance Institute (GGI) Email: [email protected] August 2012 Web: www.globalgovernance.eu Montenegro’s path to EU membership within the family.3 A very high tolerance for violence against women is present both among 30 June 2012 marked the opening of EU state institutions and within society. -

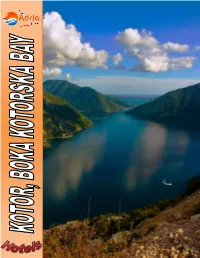

Kotor and Bay of Kotor

Kotor and Bay of Kotor Travel agency „Adria Line”, 13 Jul 1, 85310 Budva, Montenegro Tel: +382 (0)119 110, +382 (0)67 733 177, Fax: +382 (0)33 402 115 E-mail: [email protected], Web: www.adrialine.me Kotor and Bay of Kotor Kotor and The Kotor Bay Kotor Bay Boka Bay, one of the world’s 25 most beautiful bays and protected UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979. Due to its unusual look, exceptional cultural and natural features the bay is often called Europe`s southernmost fjord, but in fact it`s a submerged river canyon. The bay is composed of 4 smaller bays - Tivat, Herceg Novi, Risan and Kotor bay. The narrowest part of the bay, Verige strait, divides it into the inner and outer part. Boka Bay glows with amazing calmness and peace. Located between the Adriatic Sea and the vide limestone area the region of Boka Kotorska is under a strong influence of Mediterranean and Mountain climate. That special climate blend creates a distinguished Sub- Mediterranean climate quite different from other part of Montenegrin coast. Unique feature for Boka is the early spring when all surrounding mountains are still covered with snow while the coast flourishes with Mediterranean trees and flowers in blossom. During the winter one can enjoy the pleasant sun and calm weather on the coast while to the mountains and snow takes just 1 hour of slow drive. Along the whole coast line of the bay exist the rich distribution of Mediterranean, continental and exotic vegetation such as laurels, palms, olive-trees, orange and lemon trees, pomegranate trees, agaves, camellias, mimosas… The bay has been inhabited since antiquity and has some well preserved medieval towns.