The Role of Suction in the Adhesion of Limpets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crepidula Fornicata

NOBANIS - Marine invasive species in Nordic waters - Fact Sheet Crepidula fornicata Author of this species fact sheet: Kathe R. Jensen, Zoological Museum, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universiteteparken 15, 2100 København Ø, Denmark. Phone: +45 353-21083, E-mail: [email protected] Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet: Jensen, Kathe R. (2010): NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Crepidula fornicata – From: Identification key to marine invasive species in Nordic waters – NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, Date of access x/x/201x. Species description Species name Crepidula fornicata, Linnaeus, 1758 – Slipper limpet Synonyms Patella fornicata Linnaeus, 1758; Crepidula densata Conrad, 1871; Crepidula virginica Conrad, 1871; Crepidula maculata Rigacci, 1866; Crepidula mexicana Rigacci, 1866; Crepidula violacea Rigacci, 1866; Crepidula roseae Petuch, 1991; Crypta nautarum Mörch, 1877; Crepidula nautiloides auct. NON Lesson, 1834 (ISSG Database; Minchin, 2008). Common names Tøffelsnegl (DK, NO), Slipper limpet, American slipper limpet, Common slipper snail (UK, USA), Østerspest (NO), Ostronpest (SE), Amerikanische Pantoffelschnecke (DE), La crépidule (FR), Muiltje (NL), Seba (E). Identification Crepidula fornicata usually sit in stacks on a hard substrate, e.g., a shell of other molluscs, boulders or rocky outcroppings. Up to 13 animals have been reported in one stack, but usually 4-6 animals are seen in a stack. Individual shells are up to about 60 mm in length, cap-shaped, distinctly longer than wide. The “spire” is almost invisible, slightly skewed to the right posterior end of the shell. Shell height is highly variable. Inside the body whorl is a characteristic calcareous shell-plate (septum) behind which the visceral mass is protected. -

Feeding, Anatomy and Digestive Enzymes of False Limpet Siphonaria Guamensis

World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences 5 (1): 104-109, 2013 ISSN 2078-4589 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjfms.2013.05.01.66144 Feeding, Anatomy and Digestive Enzymes of False Limpet Siphonaria guamensis K.V.R. Murty, A. Shameem and K. Umadevi Department of Marine Living Resources Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 530 003, A.P., India Abstract: Very little information has been available in the literature on the feeding habits, anatomy and histology of digestive system of siphonariid limpets. The present study revealed Siphonaria guamensis feeds on the crustose red alga Hildenbrandia prototypus browsing on the rocks by rasping action of radula. The anatomy of digestive system of Siphonaria guamensis is similar with that of the other siphonariid limpets but the length of gut and colon are shorter than the patellogastropod limpets like Cellana radiata, patella vulgata, Fissurella barbadensis and species of Acmaea. The salivary glands are the main source of the enzyme system of Siphonaria guamensis. They contained enzymes which can act on carbohydrates, proteins and polysaccharides. The enzyme which can act on proteins was found only in salivary glands and not detected in any other part of the digestive system. No lypolytic activity was seen in any part of the digestive system of the animal. Key words: False Limpet Feeding Anatomy Digestive Enzymes INTRODUCTION tridentatum and C. minimum, where he described the morphology and histology of the digestive system at Little work has been done on the feeding, digestion length. anatomy and histology of the digestive organs of limpets Very little information has been available in the with an exception of patella vulgata (Davies and Fleure literature on the feeding methods, anatomy and histology [1], Graham [2], Stone and Morton [3], Fretter and Graham of the digestive system of siphonariid limpets. -

Zoology Department, University of Cape Town. Patella Vulgata and P. Aspersa Are Attacked by Haematopus Ostralegus, P. Aspersa Be

THE RESPONSES OF SOUTH AFRICAN PATELLID LIMPETS TO INVERTEBRATE PREDATORS G M BRANCH Zoology Department, University of Cape Town. Accepted: February 1978 ABSTRACT The starfISh Marthasterias glacialis is a generalized predator, feeding particularly on Choromytillis meridiOflalis, but also on several limpets, notably Patella longicosta. T1Iais d"bia (Gastropoda) feeds mainly on barnacles, mussels, and Patella gran"laris. The gastropods BumUJH!na delalandii and B. cincta are principally scavengers, feeding on damaged or dead animals. The responses of Patella spp. to these predators are described. P. gran"laris. P. concolor. P. compressa and P. miniata all retreat rapidly on contact. Small P. grallQtina and P. oculus respond similarly, but larger specimens react aggressively, smashing their shells downwards and often damaging the predator. The territorial species (P.longicosta. P. coch/ear and P. tablilaris) all retreat to their scan and remain clamped there. P. argenvillei and P. tablilaris are usually unresponsive, possibly because they are too large to fall prey. Cellana capensis rolls its mantle upwards to cover the shell, preventing predators from attaching. The responses and their effectiveness are discussed in relation to other behavioural patterns displayed by limpets. There is no correlation between the intensity of a prey's response to a predator and the degree of contact . ) 0 between the two in the field. 1 0 2 d e INTRODUCTION t a d A variety of limpet predators has been recorded. Several birds attack limpets by knocking ( r them off the rock, and either picking out the flesh or consuming the whole limpet and e h s regurgitating the shell: oyster catchers (Haemlltopus spp.), various gulls (LaTUS spp.) and the i l b u sheathbill (Chionus alba) (Test 1945; Feare 1971; Walker 1972). -

The American Slipper Limpet Crepidula Fornicata (L.) in the Northern Wadden Sea 70 Years After Its Introduction

Helgol Mar Res (2003) 57:27–33 DOI 10.1007/s10152-002-0119-x ORIGINAL ARTICLE D. W. Thieltges · M. Strasser · K. Reise The American slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata (L.) in the northern Wadden Sea 70 years after its introduction Received: 14 December 2001 / Accepted: 15 August 2001 / Published online: 25 September 2002 © Springer-Verlag and AWI 2002 Abstract In 1934 the American slipper limpet 1997). In the centre of its European distributional range Crepidula fornicata (L.) was first recorded in the north- a population explosion has been observed on the Atlantic ern Wadden Sea in the Sylt-Rømø basin, presumably im- coast of France, southern England and the southern ported with Dutch oysters in the preceding years. The Netherlands. This is well documented (reviewed by present account is the first investigation of the Crepidula Blanchard 1997) and sparked a variety of studies on the population since its early spread on the former oyster ecological and economic impacts of Crepidula. The eco- beds was studied in 1948. A field survey in 2000 re- logical impacts of Crepidula are manifold, and include vealed the greatest abundance of Crepidula in the inter- the following: tidal/subtidal transition zone on mussel (Mytilus edulis) (1) Accumulation of pseudofaeces and of fine sediment beds. Here, average abundance and biomass was 141 m–2 through the filtration activity of Crepidula and indi- and 30 g organic dry weight per square metre, respec- viduals protruding in stacks into the water column. tively. On tidal flats with regular and extended periods of This was reported to cause changes in sediments and emersion as well as in the subtidal with swift currents in near-bottom currents (Ehrhold et al. -

Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving on Edited by Holly Anne Foley and Karen Mattick Marine Science Center, Poulsbo, Washington

TEACHER BACKGROUND Unit 3 - Tides and the Rocky Shore Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving On Edited by Holly Anne Foley and Karen Mattick Marine Science Center, Poulsbo, Washington Key Concepts 1. Snails, limpets and chitons each crawl on rocks with a muscular foot to find food and more favorable conditions. 2. These mobile animals also adhere tightly to rocks to survive low tide and to deter predators. Background Some of the most common animals in rocky shore habitats are the snails, limpets and chitons. Unlike barnacles, these animals are mobile. They each have a muscular foot that moves in contractions which appear as waves. The wave movement propels the animal forward a minute step at a time. The wave of contraction push-pulls the animal along. The slime trail snails, limpets and chitons leave has unique chemical properties that alternately act as a glue then as a lubricant depending on the pressure placed on the slime by the animal. The stationary portion is held in place by the glue as the moving portion is easily moved over the lubricated surface. Materials For each student or pair of students: • 1 snail, limpet or chiton • 1 glass jar with a lid • sea water • washable felt marker such as an overhead transparency pen • 30 cm or so string • millimeter ruler • “Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving On” student pages Teaching Hints “Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving On” gives your students a chance to observe movement in a living marine gastropod or the similar chitons. You can readily obtain periwinkles (Littorina species) or other snails, limpets or chitons from the intertidal zone or from biological supply houses. -

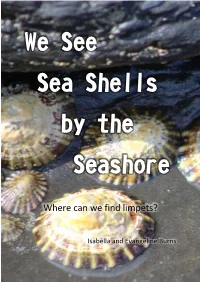

Where Can We Find Limpets?

We See Sea Shells by the Seashore Where can we find limpets? Isabella and Evangeline Burns Introduction On holidays our family often goes to the town of Ulladulla on the New South Wales south coast. When we do we always visit the rock pools and rock platform. We always look forward to these trips. We look for pretty starfish and gooey limpets and dead, dried-out blue bottles that pop when we step on them. We enjoy these expeditions so much that we wanted to learn more about some of the animals that live on the rock platform. Many animals live on the rock platform. There are starfish, sea snails and crabs. We decided to look at limpets because they have a pretty shell with many different coloured stripes and the rock platform is covered in them. Also, limpets are well known for being very strong and very difficult to pull off the rocks. This was an animal worth knowing about. Aim We wanted to find out where on the rock platform limpets live. Do they live in the wet or the dry areas of the rock platform? 2 Background Research The animal we are looking at is called the Variegated Limpet. Its scientific name is Cellana tramoserica. It is found on the south-eastern coast of Australia from Queensland to South Australia. Source: www.mesa.edu.au Limpets are gastropods. This means that that they are like snails. They have oval shells shaped like a tent to protect their soft squishy body. The soft squishy part is called their foot! They also have gills to breathe underwater. -

Gastropoda, Mollusca)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/087254; this version posted November 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. An annotated draft genome for Radix auricularia (Gastropoda, Mollusca) Tilman Schell 1,2 *, Barbara Feldmeyer 2, Hanno Schmidt 2, Bastian Greshake 3, Oliver Tills 4, Manuela Truebano 4, Simon D. Rundle 4, Juraj Paule 5, Ingo Ebersberger 3,2, Markus Pfenninger 1,2 1 Molecular Ecology Group, Institute for Ecology, Evolution and Diversity, Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 2 Adaptation and Climate, Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 3 Department for Applied Bioinformatics, Institute for Cell Biology and Neuroscience, Goethe- University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 4 Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre, Marine Institute, School of Marine Science and Engineering, Plymouth University, Plymouth, United Kingdom 5 Department of Botany and Molecular Evolution, Senckenberg Research Institute, Frankfurt am Main, Germany * Author for Correspondence: Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Tel.: +49 (0)69 75 42 18 30, E-mail: [email protected] Data deposition: BioProject: PRJNA350764, SRA: SRP092167 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/087254; this version posted November 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Habitat Preference and Population Ecology of Limpets Cellana

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Ecosystems Volume 2014, Article ID 874013, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/874013 Research Article Habitat Preference and Population Ecology of Limpets Cellana karachiensis (Winckworth) and Siphonaria siphonaria (Sowerby) at Veraval Coast of Kathiawar Peninsula, India Julee Faladu, Bhavik Vakani, Paresh Poriya, and Rahul Kundu Department of Biosciences, Saurashtra University, Rajkot, Gujarat 360005, India Correspondence should be addressed to Rahul Kundu; [email protected] Received 7 May 2014; Revised 6 July 2014; Accepted 20 July 2014; Published 17 August 2014 Academic Editor: Wen-Cheng Liu Copyright © 2014 Julee Faladu et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Present study reports the habitat preference and spatiotemporal variations in the population abundance of limpets Cellana karachiensis and Siphonaria siphonaria inhabiting rocky intertidal zones of Veraval coast, Kathiawar Peninsula, India. The entire intertidal zone of the Veraval coast was divided into five microsampling sites based on their substratum type and assemblage structure. Extensive field surveys were conducted every month in these microsampling sites and the population abundance of two limpet species was analyzed using belt transect method. The results revealed that C. karachiensis was the dominating species at microsampling Site-1 (having rocky substratum) possibly due to its ability to tolerate high desiccation, salinity, and temperature fluctuations, while the S. siphonaria was found to be the most dominating species at microsampling Site-2 (having rocky substratum with abundant algal population) possibly due to their preference for the perpetual wet areas. -

Pierce County Nearshore Species List Compiled from the Pt

Pierce County Nearshore Species List Compiled from the Pt. Defiance Park Bioblitz 2011 ID COMMON NAME √ ID COMMON NAME √ 31 Acorn barnacle X 34 Hermit crab sp. X 43 Aggregate green anemone X 35 Isopod sp. X 30 Amphipod sp. X 36 Jellyfish sp. X 95 Anemone sp. 73 Large leaf worm X 60 Barnacle nudibranch X 12 Leafy hornmouth X 48 Barnacle sp. X 74 Leather limpet 68 Bent-nose macoma 13 Leather star X 69 Black and white brittle star 14 Lewis's moonsnail X 92 Black turban X 37 Limpet sp. 63 Blood star X 75 Lined chiton X 56 Butter clam X 76 Lined ribbon worm 65 Calcareous tube worm X 108 Mask limpet X 103 California mussel X 67 Moon jellyfish X 1 California sea cucumber 32 Mossy chiton X 53 Checkered periwinkle X 61 Mottled star X 32 Chiton sp. 38 Mussel sp. X 33 Clam sp. X 77 Northern feather duster w X 70 Coonstripe shrimp 15 Northern kelp crab 59 Crab sp. X 39 Nudibranch sp. X 96 Dog welk sp. X 78 Nuttall's cockle 93 Dogwinkle sp. X 62 Ochre star X 3 Dungeness crab X 16 Opalescent (aeolid) nudib X 57 Eccentric sand dollar X 17 Orange sea cucumber X 112 Fat gaper X 18 Orange sea pen 4 Feathery shipworm X 19 Oregon triton 5 Fish-eating anemone 40 Oyster sp. 101 Flat porcelain crab 79 Pacific blue mussel X 6 Fringed tube worm 110 Pacific gaper 8 Giant (nudibranch) dendronotid 99 Pacific geoduck clam X 7 Giant barnacle X 80 Pacific oyster 9 Giant pacific octopus 97 Periwinkle sp. -

NIEA ID Guide Crepidula Fornicata Slipper Limpet

Scan for more Slipper Limpet information Species Description Scientific name: Crepidula fornicata AKA: American Slipper Limpet, Common American slippersnail Native to: North-east US Habitat: Wide range of habitats particularly in wave- protected bays, estuaries or sheltered sides of wave- This species has an oval shell, up to 5 cm in length, with a much reduced spire. The large aperture has a shelf, or septum, extending half its length. The shell is smooth with irregular growth lines and white, cream, yellow or pinkish in colour with streaks or blotches of red or brown. Slipper limpets are commonly found in curved chains of up to 12 animals. Large shells are found at the bottom of the chain, with the shells becoming progressively smaller towards the top. Crepidula fornicata is present in Northern Ireland in Belfast Lough and other coastal sites. Other records exist from around Ireland over the last century however, none of these sites are currently thought to be supporting a population. Crepidula fornicata most likely arrived in Ireland with consignments of mussels. Other possible pathways include; with consignments of oysters, on drifting materials or due to dispersal of larvae. Slipper limpet competes with, and can displace, other filter-feeding invertebrates. The species can be a serious pest of oyster and mussel beds. Slipper limpet is listed under Schedule 9 of The Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 and as such, it is an offence to release or allow this species to escape into the wild. Key ID Features Tapered point set to one -

Rocky Shore Snails As Material for Projects (With a Key for Their Identification)

Field Studies, 10, (2003) 601 - 634 ROCKY SHORE SNAILS AS MATERIAL FOR PROJECTS (WITH A KEY FOR THEIR IDENTIFICATION) J. H. CROTHERS Egypt Cottage, Fair Cross, Washford, Watchet, Somerset TA23 0LY ABSTRACT Rocky sea shores are amongst the best habitats in which to carry out biological field projects. In that habitat, marine snails (prosobranchs) offer the most opportunities for individual investigations, being easy to find, to identify, to count and to measure and beng sufficiently robust to survive the experience. A key is provided for the identification of the larger species and suggestions are made for investigations to exploit selected features of individual species. INTRODUCTION Rocky sea shores offer one of the best habitats for individual or group investigations. Not only is there de facto public access (once you have got there) but also the physical factors that dominate the environment - tides (inundation versus desiccation), waves, heat, cold, light, dark, salinity etc. - change significantly over a few metres in distance. As a bonus, most of the fauna and flora lives out on the open rock surface and patterns of distribution may be clearly visible to the naked eye. Finally, they are amongst the most ‘natural’ of habitats in the British Isles; unless there has been an oil spill, rocky sea shores are unlikely to have been greatly affected by covert human activity. Some 270 species of marine snail (Phylum Mollusca, Class Gastropoda; Sub-Class Prosobranchia) live in the seas around the British Isles (Graham, 1988) and their empty shells may be found on many beaches. Most of these species are small (less than 3 mm long) or live beneath the tidemarks. -

MOLLUSCS Species Names – for Consultation 1

MOLLUSCS species names – for consultation English name ‘Standard’ Gaelic name Gen Scientific name Notes Neologisms in italics der MOLLUSC moileasg m MOLLUSCS moileasgan SEASHELL slige mhara f SEASHELLS sligean mara SHELLFISH (singular) maorach m SHELLFISH (plural) maoraich UNIVALVE SHELLFISH aon-mhogalach m (singular) UNIVALVE SHELLFISH aon-mhogalaich (plural) BIVALVE SHELLFISH dà-mhogalach m (singular) BIVALVE SHELLFISH dà-mhogalaich (plural) LIMPET (general) bàirneach f LIMPETS bàirnich common limpet bàirneach chumanta f Patella vulgata ‘common limpet’ slit limpet bàirneach eagach f Emarginula fissura ‘notched limpet’ keyhole limpet bàirneach thollta f Diodora graeca ‘holed limpet’ china limpet bàirneach dhromanach f Patella ulyssiponensis ‘ridged limpet’ blue-rayed limpet copan Moire m Patella pellucida ‘The Virgin Mary’s cup’ tortoiseshell limpet bàirneach riabhach f Testudinalia ‘brindled limpet’ testudinalis white tortoiseshell bàirneach bhàn f Tectura virginea ‘fair limpet’ limpet TOP SHELL brùiteag f TOP SHELLS brùiteagan f painted top brùiteag dhotamain f Calliostoma ‘spinning top shell’ zizyphinum turban top brùiteag thurbain f Gibbula magus ‘turban top shell’ grey top brùiteag liath f Gibbula cineraria ‘grey top shell’ flat top brùiteag thollta f Gibbula umbilicalis ‘holed top shell’ pheasant shell slige easaig f Tricolia pullus ‘pheasant shell’ WINKLE (general) faochag f WINKLES faochagan f banded chink shell faochag chlaiseach bhannach f Lacuna vincta ‘banded grooved winkle’ common winkle faochag chumanta f Littorina littorea ‘common winkle’ rough winkle (group) faochag gharbh f Littorina spp. ‘rough winkle’ small winkle faochag bheag f Melarhaphe neritoides ‘small winkle’ flat winkle (2 species) faochag rèidh f Littorina mariae & L. ‘flat winkle’ 1 MOLLUSCS species names – for consultation littoralis mudsnail (group) seilcheag làthaich f Fam.