ANTARCTICA: View from a Gateway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J.S. Antarctic Projects Officer N

J.S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER N VOLUME III NUMBER 5 JANUARY 1962 Wednesday, January 17 [1912]. -- Camp 69. T. -220 at start. Night -21°. The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected. Great God! this is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here, and the wind may be our friend to--morrow. We have had a fat Polar hoosh in spite of our chagrin, and feel com- fortable inside -- added a small stick of chocolate and the queer taste of a cigarette brought by Wilson. Now for the run home and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it. Thursday morning, January 18. -- Decided after suing up all observations that we were 3.5 miles away from the Pole -- one mile beyond it and 3 to the right. More or less in this direction Bowers saw a cairn or tent. We have just arrived at this tent, 2 miles from our camp, therefore about li miles from the Pole. In the tent we find a record of five Norwegians having been here, as follows: Roald Amundsen Olav Olavson Bjaaland Humor Hanssen Svorre H. Hassel Oscar Wisting. 16 Dec. 1911. Captain Robert F. Scott, Scotts Lest Expedition, arranged by Leonard Huxley, vol. I, pp. 374-375. Volume III, No. 5 January 1962 CONTENTS The Month in Review 1 International Flights in the Antarctic 2 South Pole -- Fifty Years After 4 Dirty Diamond Mine 4 Topo North Completed 5 Marine Life Under Ross Ice Shelf 6 Lakes with Warm Water 7 The Fiftieth in Washington 8 Suggestions for Reading 9 New Zealand Memorial to Admiral Byrd 11 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 12 Material for this issue of the Bulletin was adapted from press releases issued by the Department of Defense and the National Science Foundation and from incoming dispatches. -

Ross Sea Voyage 11 February - 13 March, 2015

Ross Sea Voyage 11 February - 13 March, 2015 Journey to the Ross Sea in this new cruise organised by Oceanwide Expeditions and sold by Gane and Marshall. This exciting new expedition (the first voyage took place in 2013) departs from New Zealand and visits Campbell Island, the Bay of Whales, Ross Island (including a tour of the McMurdo Station as well as the huts used by Shackleton and Scott during their famous expedition), and Kainan Bay, from where the explorers Amundsen and Shirase approached the Antarctic ice- shelf in 1911 and 1912, respectively. From Kainan, you will sail to the little-explored Peter I Island, and then on to the Antarctic Peninsula. During the voyage you will have many opportunities to go ashore, with regular expeditions from the cruise ship to the shore via zodiacs or helicopter. You will travel on Oceanwide’s strongest ice- vessel, the M/V Ortelius. This small and extremely comfortable cruise ship carries only 100 guests, ensuring you an intimate cruise. Day 1: Departure from Bluff, New Zealand Passengers embark and depart from the port of Bluff, New Zealand. Day 2: At sea At sea en-route to Campbell Island Day 3: Campbell Island Today we reach Campbell Island, which wespend the day exploring. This sub-Antarctic island is formally part of New Zealand, but it’s entirely uninhabited. It’s a designated reserve and World Your Financial Protection All monies paid by you for the air holiday package shown [or flights if appropriate] are ATOL protected by the Civil Aviation Authority. Our ATOL number is ATOL 3145. -

Balleny Paper

XXIII ATCM/WP31 May, 1999 Original: English Agenda Item 7f) CEP II Agenda Item 5e) Proposed Balleny Island Specially Protected Area Submitted by New Zealand Error! Reference source not found. Proposed Balleny Island Specially Protected Area Summary New Zealand proposes that consideration be given to Specially Protected Area No.4 concerning Sabrina Island in the Balleny Islands being enlarged to include other Balleny Islands, together with a marine area surrounding the islands. A copy of the draft management plan is provided for information and consultation. The designation of an enlarged SPA is considered necessary to protect the unique and special ecological, scientific and aesthetic values of the area and to establish an archipelagic SPA in the Ross Sea region. Background At the Fourth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting in Santiago in 1966, a small island in the Balleny Islands was designated as Specially Protected Area No. 4. Sabrina Island was accorded this status in recognition that the Balleny Islands are the most northerly Antarctic land in the Ross Sea region and support fauna and flora which reflect many circumpolar distributions at this latitude. The Balleny Islands (together with Scott Island) are the only truly marine or oceanic islands (rather than continental islands) on this side of Antarctica making them distinctive from any neighbouring areas. Located 250km off the coast of Antarctica in the northern Ross Sea, the Balleny Islands are a rare “oasis” of land in the Southern Ocean and their position is far enough north to be directly in the path of circumpolar ocean currents. Consequently their presence is likely to create upwellings, which tend to bring nutrient-rich deep water closer to the surface, which in turn makes the area biologically very productive. -

The Potential Hazard of Antarctic Ice Shelf Carving in New Zealand Territorial Waters

PCAS 16 (2013/2014) Critical Literature Review (ANTA602) The Potential Hazard of Antarctic Ice Shelf Carving in New Zealand Territorial Waters. Errin Rowan Student ID: 95607115 Word Count: 3049 Abstract: The Antarctic Peninsula is the one region of the Southern Ocean that has experienced large temperature changes over the past century resulting in the release of large ice bergs into the Southern Ocean. The glacial calving process is based on glacier ice flow dynamics as breaking rates are controlled by ice velocity changes and retreat. With increased continental warming and consequently melting there will be an increase in ice-berg calving frequency and movement from the Antarctic continent. GIS satellite monitoring of the Antarctic has provided useful images of the migration of icebergs. Recent advances in the use of geographic information systems and the ability to monitor the movement of icebergs and changes in ice sheets makes the potential for predicting the impacts on the Southern Ocean easier. This literature review considers the question – with increased iceberg frequency what are the potential impacts of ice-berg migration on Southern Ocean logistics. 1 Contents Page 1 Title page and Abstract 2 Contents 3 Introduction 3 Antarctic Glacier Processes 4 Current State of Calving Processes 5 Implications and Effects of Icebergs in the Southern Ocean 6 Iceberg Drift in the Southern Ocean 6 GIS Tracking of Ice Bergs in the Southern Ocean 7 Changes in Ice Calving Mechanics and Affects in the Near future 8 Icebergs Negatively Affecting New Zealand’s Interests in the Southern Ocean 8 Conclusion 9 Reference List 2 Introduction In a warming world, Polar Regions have been experiencing dramatic changes in atmospheric temperatures. -

Origin and Evolution of the Sub-Antarctic Islands: the Foundation

Papersnd a Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 141 (1), 2007 35 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE SUB-ANTARCTIC ISLANDS: THE FOUNDATION by Patrick G. Quilty (with 23 text-figures and two tables) Quilty, P.G. 2007 (23:xi): Origin and evolution of the sub-Antarctic islands: the foundation.Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 141 (1): 35-58. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.141.1.35 ISSN 0080-4703. School of Earth Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 79, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia. Email: P.Quil [email protected] Sub-Antarctic islands have a diversity of origins in detail but most are volcanic and very young suggesting that they are short-lived and that the distribution would have been very differenta few million years ago. 'They contrast with the common tourist brochure concept of oceanic islands. As the Antarctic Plate is virtually static, the islands seldom show signs of association with long-lived linear island chains and most thus stand alone. Longer-lived islands are either on submarine plateaux or are continental remnants of the dispersion of Gondwana. The islands are classified in relation to raised sea-floor, transform fault, triple junction, subduction zone, submarine plateau, submerged continent or continental. Many are difficult of access and poorly known geologically. Their geological history controls their many other roles such as sites as observatories, or for study of colonisation, evolution and speciation rates. Key Words: Sub-Antarctic islands, geological evolution, Macquarie Island, Balleny Islands, Scott Island, Campbell Island, Antipodes Island, Auckland Islands, Enderby Island, Peter I Island, Islas Diego Ramirez, South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands, Bouvetoya, Gough Island, Marion Island, Prince Edward Island, Iles Crozet, Amsterdam Island, St Paul Island, Kerguelen Plateau, Iles Kerguelen, Heard Island, McDonald Island. -

Managing Tourism in Antarctica – a Framework for the Future

Managing Tourism in Antarctica – A Framework for the Future Harry Maher A thesis submitted for the degree of Masters of Tourism At the University of Otago, Dunedin New Zealand Date: 19 December 2005 i Abstract Antarctic tourism has been the subject of significant debate in recent years, not only within the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) but also in the wider community. A relatively recent but now well-established industry, tourism in Antarctica is characterised by high regional growth rates and the potential for significant impacts on the environments where it occurs. This thesis addresses the research question ‘Is the current regulatory system for managing tourism in Antarctica adequate to protect the Antarctic environment?’ It examines the general theories of management of tourism and recreation in protected and wilderness areas. The importance of the relationship between site values, tourism activities, impacts and management responses is highlighted. It is noted that contemporary protected area managers inevitably put in place robust and binding legislation, site-specific management plans, and management interventions to manage wilderness areas. The tourism management framework for Antarctica is presented, in both its historical and contemporary contests. The historical and current size and nature of the Antarctic tourist industry is analysed and presented, along with an in- depth examination of the values and attributes of the sites where that activity occurs. The actual and potential impacts of tourism in general and of the current levels of tourism in Antarctica are then discussed. A discussion regarding the adequacy of the current ATS tourism management regime is presented. The system is found to be inadequate across a range of critical factors. -

Antarctic Expedition 1996 AΚΑДЕМИΚ ШОΚΑΛЬСΚИЙ

Antarctic Expedition 1996 AΚΑДЕМИΚ ШОΚΑΛЬСΚИЙ Die Route: Tasmanien – Macquarie Island – Ross Island – Neuseeland. Mon 22.1.1996 15:00 Embark the Akademik Shokalskiy 17:00 The Akademik Shokalskiy departs Hobart, Tasmania Our ship is the Akademik Shokalskiy built in Finland in 1983 and origi- nally designed as a research vessel. She provides comfortable accom- modation tor 38 passengers (there are 19 twin occupancy cabins). Measuring 236 ft. (72 m) in length and 42 ft. (13 m) in breadth, the Akademik Shokalskiy is a steel built, ice strengthened vessel perfect for cruising the Subantarctic and Antarctic. Of Russian registry, she will be manned by an enthusiastic Russian crew of about 30 with extensive ex- perience in ice conditions. Powered by two 1560 horse power diesel engines, she is capable of sea speeds ot 12 knots. She has a good anti-roll system and a range of 50 days independent operation. Da wir eine ungerade Anzahl von Teilnehmern sind, bekommt einer Tue 23.1. – Thu 25.1.1996 Enroute to Maquarie Island von uns eine Einzelkabine. Der Zufall sorgt dafür, daß ich derjenige bin. Mit hervorragender Sicht voraus über den Bug der Shokalskiy . my cabin Fri 26.1.1996 Macquarie Island The Akademik Shokalskiy arrives Sandy Bay, Maquarie Island Die subantarktische Insel Macquarie Island liegt ca. 1500 km südöstlich von Tasmanien und etwa 1300 km nördlich der Antarktis. Die 128 km² große Insel ist etwa 5 km breit und 34 km lang. Das Klima ist feucht, stürmisch und kühl. Je nach Höhenlage liegt die Jahresmitteltemperatur zwischen 0 und 4,4 Grad Celsius. -

Identifying Artefacts Associated with Captain Robert Falcon

IDENTIFYING ARTEFACTS ASSOCIATED WITH CAPTAIN ROBERT FALCON SCOTT’S BRITISH ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1910 – 1913 HELD IN CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND CONSIDERED SUITABLE FOR EXHIBITION. Captain Robert Falcon Scott and members of the British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13, Cape Evans, Antarctica, 1911. Credit Alexander Turnbull Library Collection Fiona Wills Personal Project Gateway Canterbury, Antarctic Studies February 2008 1 F Wills. G.C.A.S. February 2008. Between 1895 and 1917 (known as the heroic era of Antarctic exploration) a number of expeditions set out to explore and open Antarctica to the world. Given New Zealand’s proximity to the Ross Sea region of Antarctica, three of the heroic era expeditions departed and returned to/from Antarctica from the port of Lyttelton, Canterbury, New Zealand. As a result of the longstanding relationship with the people of Canterbury, the province’s organisations such as the Canterbury Museum, Lyttelton Museum and Antarctic Heritage Trust collectively house one of the world’s leading publicly accessible artefact collections from this period of Antarctic exploration. A century on the public fascination with the expeditions remains. The upcoming centenary of one of the most famous of the expeditions, the British Antarctic (Terra Nova) Expedition 1910-1913, led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott, provides unique opportunities to celebrate and profile the expedition and its leader, a man who has gone on to become legendary in the world of exploration. This paper identifies key artefacts associated with the expedition currently held by Canterbury institutions which have been identified as potentially suitable for public exhibition. Criteria was based on factors such as historical significance, visual impact and their ability to be exhibited. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 September 2014 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hodgson, D.A. and Graham, A.G.C. and Roberts, S.J. and Bentley, M.J. and O¡ Cofaigh, C. and Verleyen, E. and Vyverman, W. and Jomelli, V. and Favier, V. and Brunstein, D. and Verfaillie, D. and Colhoun, E.A. and Saunders, K.M. and Selkirk, P.M. and Mackintosh, A. and Hedding, D.W. and Nel, W. and Hall, K. and McGlone, M.S. and Van der Putten, N. and Dickens, W.A. and Smith, J.A. (2014) 'Terrestrial and submarine evidence for the extent and timing of the Last Glacial Maximum and the onset of deglaciation on the maritime-Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands.', Quaternary science reviews., 100 . pp. 137-158. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.12.001 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. -

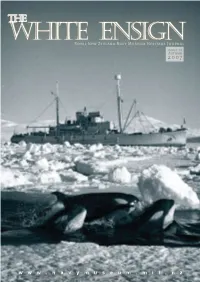

White-Ensign-Issue-1.Pdf

THE WHITERoyal New ZealandENSIGN Navy Museum Heritage Journal issue 01 Autumn 2007 THE WHITE ENSIGN www.navymuseum.mil.nzISSUE 01 AUTUMN 2007 Director’s Message CONTENTS Page 16 THE Te Waka Taonga o Te Taua Moana o Aotearoa WHITE ENSIGN Welcome Royal New Zealand Navy Museum Heritage Journal The White Ensign is the official Navy Museum issue 01 Heritage Journal. This publication at present to the first edition of The White Ensign, Autumn comes out three times per year. the Royal New Zealand Navy Museum’s Heritage Journal. 2007 Views expressed in The White Ensign are not necessarily those of the RNZN. Contributions, Dits, Feedback and Enquiries: Contributions and feedback are welcomed. As a nation we readily identify with the gallantry and sacrifice of 02 Director’s Message Submit copy of letters for publication in Microsoft New Zealand’s military personnel at Gallipoli, the Somme and Word, on diskette or email. Articles between 300 04 Feature Article - An Overview of the Navy’s Involvement in Antarctica - 1000 words, digital photos at least 200 dpi. Crete. Few of us however, share the same knowledge of the Reprinting of items are encouraged if the Navy immense contribution New Zealanders have made to our nation Museum is acknowledged. All copy and enquiries through service at sea, in firstly the Royal Navy, then the New 08 From the Collection - Fry’s Pure Concentrated Cocoa Tin to be directed to the Editor. Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, and then from 1941, the Royal 10 Photos from the Archives White Ensign Editorial Advisers: New Zealand Navy. -

A Marine Reserve Forthe Ross

ANTARCTIC OCEAN LEGACY: A MARINE RESERVE FOR THE ROSS SEA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In October 2011, the Antarctic protection for is the Ross Sea call to protect vital Ross Sea Ocean Alliance proposed the region, including the Balleny habitats including the whole creation of a network of marine Islands, the Paci!c seamounts continental slope and shelf because protected areas and no-take and the Ross Sea embayment. of their environmental and scienti!c marine reserves in 19 speci!c This report describes our signi!cance. areas in the Southern Ocean proposal and the rationale for its This report starts with a description around Antarctica. The Antarctic designation. This is the !rst in a of the fascinating ecosystems in Ocean Alliance is a coalition of series of “Antarctic Ocean Legacy” the Ross Sea region. It examines environmental organisations that proposals from the Alliance. is calling for large-scale protection the marine research that has of critical marine habitats. For the Ross Sea region, our been done to date in light of two proposal is to establish a fully useful scenarios developed by the The Commission for the protected marine reserve of United States and New Zealand Conservation of Antarctic Marine governments. We conduct an approximately 3.6 million square Living Resources (CCAMLR), the analysis of those scenarios and kilometers. This proposal is justi!ed body that regulates this marine conclude that the best elements based on the work of scientists, environment, has set a target date of all this work can be brought governments and non-government of 2012 for establishing the initial together in a combined and organisations (NGOs) over the areas in a network of Antarctic enhanced proposal that truly past !ve years highlighting the marine protected areas. -

Peri-Antarctic Islands

PERI-ANTARCTIC ISLANDS R. K. Headland 8 January 2019 SPRI, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> These are the 19 islands and archipelagos around Antarctica which are included in the area of interest of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research. The Peri-Antarctic Islands include the Sub-Antarctic ones and those farther south with associated features. The positions given are approximately the middle point for smaller islands and their limits for larger ones and groups. Names are given in the form recommended by the Union Géographique International. Sightings, landings, and winterings are, in all cases, the earliest definite dates; there may have been previous ones for some islands. The glacierized area is currently decreasing on several islands; thus proportions for some may be less than listed. Territorial sovereignty over some islands is disputed and some have changed by agreement. In easterly order, from the prime meridian, the islands are: BOUVETØYA; 54·42°S, 03·37°E One isolated volcanic island (with fumaroles) and offlier; in the Southern Ocean (the most isolated land on Earth). Area: 54 km2. Highest elevation: 778 m (Olavtoppen). 93% glacierized. Sighted 1739, first landing 1822 (by sealers). Uninhabited, no wintering population recorded. Norwegian dependency (Biland). PRINCE EDWARD ISLANDS; 46·60° to 46·97°S, 37·58° to 38·02°E Two islands (Marion Island and Prince Edward Island) with offliers, 19 km apart, of volcanic origin (Marion Island active in 1980); in the Indian Ocean. Area: 335 km2 (290 km2 and 45 km2 respectively). Highest elevation: 1231 m (Mascarin Peak, Marion Island).