Exploring Healthcare Alliances in Rural Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hospital Networks: Perspective from Four Years of the Individual Market Exchanges Mckinsey Center for U.S

Hospital networks: Perspective from four years of the individual market exchanges McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform May 2017 Any use of this material without specific permission of McKinsey & Company is strictly prohibited Key takeaways The proportion of narrowed The trend toward managed Narrowed networks continue to 1 networks continues to rise 2 plan design also continues. In 3 offer price advantages to (53% in 2017, up from 48% in the 2017 silver tier, more than consumers. In the 2017 silver 2014). In the 2017 individual 80% of narrowed network plans, tier, plans with broad networks market, both incumbent carriers and over half of the broad were priced ~18% higher than and new entrants carriers network plans, had managed narrowed network plans offered narrow networks designs predominantly Consumer choice is becoming Consumers who select narrowed In both 2014 and 2015 (most 4 more limited. In 2017, 29% of 5 networks in 2017 may have less 6 recent available data), narrowed QHP-eligible individuals had choice of specialty facilities network plans performed only narrowed network plans (e.g., children’s hospitals) but, in better financially, on average, available to them in the silver the aggregate, have access to than broad network plans did tier (up from 10% in 2014) hospitals with quality ratings similar to those in broad networks Definitions of "narrowed networks" and other specialized terms can be found in the glossary at the end of this document. McKinsey & Company 2 1 The proportion of narrowed networks continues to rise Network breadth by carrier status Ultra-narrow Narrow Tiered Broad N = number of networks1,2 Incumbents are using more narrowed networks New entrants2 primarily used narrowed More than half of networks are narrowed networks in 2017 1,883 1,703 37 2,410 2,782 2,524 1,740 19 21 24 20 18 18 21 25 21 23 25 28 28 4 38 6 5 5 4 4 0 52 47 53 54 53 47 38 2016 2017 2017 2014 2015 2016 2017 Carriers that remained in the market New entrants National view in both years 1 Networks were counted at a state rating area level. -

PEAES Guide: Philadelphia Contributionship

PEAES Guide: Philadelphia Contributionship http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/contribution.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One Philadelphia Contributionship 212 South Fourth Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 627-1752 Contact Person: Carol Wojtowicz Smith, Curator/Archivist, [email protected] Overview: In 1752, Benjamin Franklin brought together a group of Philadelphians to create the first North American property insurance company. They met at the Widow Pratt's (The Royal Standard Tavern on Market Street), selected two surveyors, and laid down rules stipulating that at least one of them survey each house and write up reports that would be discussed by the entire Board, which would make decisions about the extent and rate of insurance. Franklin named the company The Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire. Already in 1736 he had helped to found Philadelphia's first fire brigade, the Union Fire Company. The Contributinship was a mutual insurance company that pooled risks. They based its method of operation (and name) on that of the Amicable Contributionship of London, founded in 1696. The new company was conservative in its underwriting, sending surveyors to inspect each building before insuring it. Accepted properties sported fire marks: four clasped gilded hands mounted on wood plaques. The actual cost of the survey was presumably deducted from the 10 shillings earnest money paid by every person insuring in the society. This also covered the costs of the policy and the "badge" or fire mark. Insurance at this time was limited to properties in Pennsylvania located within a ten mile radius from the center of Philadelphia. -

Pennsylvania Hospital Campus

Diabetes Education Main Entrance 2nd Floor McClelland Conference Center South Gatehouse 1st Floor Great Court Administration Bargain Shop AYER 2nd Floor Historic Library North Gatehouse 3rd Floor Surgical Amphitheatre Medical Volunteer Services PINE BUILDING Library Emergency Department Entrance 9 TH STREET WIDENER Physician Oces Admissions Outpatient Laboratories 8 TH STREET CATHCART Emergency Department Outpatient Registration SPRUCE STREET Radiology Gift Shop Pennsylvania Hospital SCHIEDT Women’s Imaging Center Chapel 800 Spruce Street PRESTON Cafeteria Welcome Center Patient and Guest Services Zubrow Auditorium Philadelphia, PA 19107 Women’s Imaging Center ATM Building Location Map MAIN CAMPUS/FLOOR PLAN on reverse side. EMERGENCY FLOOR/ FLOOR/ 9th Street ENTRANCE DESTINATION BUILDING DESTINATION BUILDING (AMBULANCES) Medical Records/ Cardiac Radiology Film Library 1/Preston Catheterization B/Schiedt Widener Schiedt Outpatient Pharmacy 1/Preston Emergency Cheston Department 1/Schiedt EMERGENCY Conference Room 2/Preston Heart Station 3/Schiedt DEPARTMENT Intensive Care Nursery 2/Preston Critical Care 3/Schiedt EMERGENCY 2nd Floor ENTRANCE Labor and Delivery 3/Preston Observation Unit 4/Schiedt McClelland Conference Center Scheidt Elevators Rooms 450–467 4/Preston Dialysis 4/Schiedt Widener Elevators Rooms 550–567 5/Preston Rooms 500–516 5/Schiedt Pine Rooms 650–668 6/Preston Rooms 600–617 6/Schiedt X-Ray Rooms 750–767 7/Preston Rooms 700–717 7/Schiedt Building Pre-Admission Testing Cashier 1/Cathcart Discharge Unit 9/Schiedt 1st Floor -

CAREER GUIDE for RESIDENTS

Winter 2017 CAREER GUIDE for RESIDENTS Featuring: • Finding a job that fits • Fixing the system to fight burnout • Understanding nocturnists • A shift in hospital-physician affiliations • Taking communication skills seriously • Millennials, the same doctors in a changed environment • Negotiating an Employment Contract Create your legacy Hospitalists Legacy Health Portland, Oregon At Legacy Health, our legacy is doing what’s best for our patients, our people, our community and our world. Our fundamental responsibility is to improve the health of everyone and everything we touch–to create a legacy that truly lives on. Ours is a legacy of health and community. Of respect and responsibility. Of quality and innovation. It’s the legacy we create every day at Legacy Health. And, if you join our team, it’s yours. Located in the beautiful Pacific Northwest, Legacy is currently seeking experienced Hospitalists to join our dynamic and well established yet expanding Hospitalist Program. Enjoy unique staffing and flexible scheduling with easy access to a wide variety of specialists. You’ll have the opportunity to participate in inpatient care and teaching of medical residents and interns. Successful candidates will have the following education and experience: • Graduate of four-year U.S. Medical School or equivalent • Residency completed in IM or FP • Board Certified in IM or FP • Clinical experience in IM or FP • Board eligible or board certified in IM or FP The spectacular Columbia River Gorge and majestic Cascade Mountains surround Portland. The beautiful ocean beaches of the northwest and fantastic skiing at Mt. Hood are within a 90-minute drive. The temperate four-season climate, spectacular views and abundance of cultural and outdoor activities, along with five-star restaurants, sporting attractions, and outstanding schools, make Portland an ideal place to live. -

1985 Commencement Program, University Archives, University Of

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Two Hundred Twenty-Ninth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees PHILADELPHIA CIVIC CENTER CONVENTION HALL Monday, May 20, 1985 Guests will find this diagram helpful in locating the Contents on the opposite page under Degrees in approximate seating of the degree candidates. The Course. Reference to the paragraph on page seven seating roughly corresponds to the order by school describing the colors of the candidates' hoods ac- in which the candidates for degrees are presented, cording to their fields of study may further assist beginning at top left with the College of Arts and guests in placing the locations of the various Sciences. The actual sequence is shown in the schools. Contents Page Seating Diagram of the Graduating Students 2 The Commencement Ceremony 4 Commencement Notes 6 Degrees in Course 8 • The College of Arts and Sciences 8 The College of General Studies 16 The School of Engineering and Applied Science 17 The Wharton School 25 The Wharton Evening School 29 The Wharton Graduate Division 31 The School of Nursing 35 The School of Medicine 38 v The Law School 39 3 The Graduate School of Fine Arts 41 ,/ The School of Dental Medicine 44 The School of Veterinary Medicine 45 • The Graduate School of Education 46 The School of Social Work 48 The Annenberg School of Communications 49 3The Graduate Faculties 49 Certificates 55 General Honors Program 55 Dental Hygiene 55 Advanced Dental Education 55 Social Work 56 Education 56 Fine Arts 56 Commissions 57 Army 57 Navy 57 Principal Undergraduate Academic Honor Societies 58 Faculty Honors 60 Prizes and Awards 64 Class of 1935 70 Events Following Commencement 71 The Commencement Marshals 72 Academic Honors Insert The Commencement Ceremony MUSIC Valley Forge Military Academy and Junior College Regimental Band DALE G. -

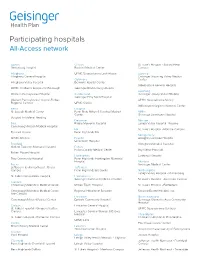

Participating Hospitals All-Access Network

Participating hospitals All-Access network Adams Clinton St. Luke’s Hospital - Sacred Heart Gettysburg Hospital Bucktail Medical Center Campus Allegheny UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven Luzerne Allegheny General Hospital Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Columbia Center Allegheny Valley Hospital Berwick Hospital Center Wilkes-Barre General Hospital UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Geisinger Bloomsburg Hospital Lycoming Western Pennsylvania Hospital Cumberland Geisinger Jersey Shore Hospital Geisinger Holy Spirit Hospital Western Pennsylvania Hospital-Forbes UPMC Susquehanna Muncy Regional Campus UPMC Carlisle Williamsport Regional Medical Center Berks Dauphin St. Joseph Medical Center Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Mifflin Center Geisinger Lewistown Hospital Surgical Institute of Reading Delaware Monroe Blair Riddle Memorial Hospital Lehigh Valley Hospital - Pocono Conemaugh Nason Medical Hospital Elk St. Luke’s Hospital - Monroe Campus Tyrone Hospital Penn Highlands Elk Montgomery UPMC Altoona Fayette Abington Lansdale Hospital Uniontown Hospital Bradford Abington Memorial Hospital Guthrie Towanda Memorial Hospital Fulton Fulton County Medical Center Bryn Mawr Hospital Robert Packer Hospital Huntingdon Lankenau Hospital Troy Community Hospital Penn Highlands Huntingdon Memorial Hospital Montour Bucks Geisinger Medical Center Jefferson Health Northeast - Bucks Jefferson Campus Penn Highlands Brookville Northampton Lehigh Valley Hospital - Muhlenberg St. Luke's Quakertown Hospital Lackawanna Geisinger Community Medical Center St. Luke’s Hospital - Anderson Campus Cambria Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Moses Taylor Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Bethlehem Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center - Regional Hospital of Scranton Steward Easton Hospital, Inc. Lee Campus Lancaster Northumberland Conemaugh Miners Medical Center Ephrata Community Hospital Geisinger Shamokin Area Community Hospital Carbon Lancaster General Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Gnaden Huetten UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury Campus Lancaster General Women & Babies Hospital Philadelphia St. -

Critical Information Could Your Patients Benefit

To view this email as a web page, go here. September 30, 2018 Critical Information Everything you need to know Could your Patients Benefit from a Medicare Advantage Plan Powered by Hartford HealthCare? Hartford HealthCare and Tufts Health Plan have launched CarePartners of Connecticut, a new health insurance company that brings together the healthcare expertise of HHC with the insurance plan experience of Tufts Health Plan. CarePartners of Connecticut will offer Medicare Advantage plans to eligible beneficiaries, starting with the Open Enrollment period that begins Oct. 15. Recently, Dr. Jim Cardon explained the joint venture and the benefits for patients in an article in Network News. Read the Q&A here. Drs. Yu, Lawrence to Lead Tweeting for CME’s on Breast Cancer Discussion on Oct. 1 We’ve created a new way for you to earn Continuing Medical Education (CME) hours to keep abreast of the latest innovations in healthcare: Tweeting for CME’s. This unique partnership between the Hartford HealthCare Office of Continuing Education and the Planning & Marketing Department allows you to take part in a Twitter chat led by Hartford HealthCare experts and apply for CMEs as a result. "Each onehour chat discusses a deidentified patient case and/or peerreviewed journal article," said Hillary Landry, professional education manager with Hartford HealthCare's Office of Experience, Engagement & Organizational Development. "Participants wishing to earn CMEs would review the case or article in advance, then attend and participate in the chat by providing their insights using a specific Twitter hashtag: #CMEHHC." The next chat takes place tomorrow, Oct. -

Pennsylvania Hospital Board of Managers Executive Committee

PENNSYLVANIA HOSPITAL BOARD OF MANAGERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Resolution to Approve the Pennsylvania Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Health System’s Community Health Needs Assessment Implementation Strategy Written Plan INTENTION: Pennsylvania Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Health System (“PAH”) a component of the University of Pennsylvania Health System (“UPHS”) and Penn Medicine, is organized as a not- for- profit 501(c)(3) hospital. PAH is committed to identifying, prioritizing and serving the health needs of the community it serves. In fulfillment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, PAH has performed a Community Health Needs Assessment (“CHNA”) and in conjunction with UPHS, prepared a written implementation strategy (“CHNA Implementation Plan”). The purpose of the CHNA is to identify and assess the health needs of, and take into account input from persons who represent the broad interests of the community served by PAH. The CHNA Implementation Plan for Fiscal Year 2013, as presented to the Board of Managers through its Executive Committee and attached as Exhibit A sets forth PAH’s assessment and implementation strategies. ACCORDINGLY, IT IS HEREBY RESOLVED, that the PAH CHNA Implementation Plan as described in the foregoing Intention is hereby approved. FURTHER RESOLVED, that the proper officers of PAH be, and each of them hereby is, authorized to execute and deliver such additional documents, and to take such additional actions as may be necessary or desirable in the opinion of the individual so -

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 14, folder “5/12/75 - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 14 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Vol. 21 Feb.-March 1975 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY BY PARC, THE PHILADELPHIA ASSOCIATION FOR RETARDED CITIZENS FIRST LADY TO BE HONORED Mrs. Gerald R. Ford will be citizens are invited to attend the "guest of honor at PARC's Silver dinner. The cost of attending is Anniversary Dinner to be held at $25 per person. More details the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, about making reservations may be Monday, May 12. She will be the obtained by calling Mrs. Eleanor recipient of " The PARC Marritz at PARC's office, LO. -

Designated Acute Care Hospital Stroke Centers 180424

Acute Stroke -ready; Comprehensive stroke COUNTY FACILITY NAME CITY ZIP Center or Primary Stroke Center? MONTGOMERY Abington Memorial Hospital Comprehensive stroke Center Abington 19001 ALLEGHENY Allegheny General Hospital Comprehensive Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15212 CUMBERLAND Carlisle Regional Medical Center Primary Stroke Center Carlisle 17015 FRANKLIN Chambersburg Hospital Primary Stroke Center Chambersburg 17201 CHESTER Chester County Hospital – Chester County Primary Stroke Center West Chester 19380 CAMBRIA Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Primary Stroke Center Johnstown 15905 BLAIR Conemaugh Nason Medical Center Acute Stroke -ready Roaring Spring 16673 BUCKS Doylestown Hospital Primary Stroke Center Doylestown 18901 MONTGOMERY Einstein Medical Center Montgomery Primary Stroke Center East Norriton 19403 LANCASTER Ephrata Community Hospital Primary Stroke Center Ephrata 17522 WESTMORELAND Excela Health Frick Hospital Primary Stroke Center Westmoreland 15666 WESTMORELAND Excela Health Latrobe Hospital Primary Stroke Center Latrobe 15650 WESTMORELAND Excela Health Westmoreland Hospital Primary Stroke Center Greensburg 15601 LACKAWANNA Geisinger Community Medical Center – Scranton - Lackawanna County Primary Stroke Center Scranton 18510 MONTOUR Geisinger Medical Center – Montour County Primary Stroke Center Danville 17822 LUZERNE Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center, Wilkes-Barre – Luzerne County Primary Stroke Center Wilkes Barre 18711 ADAMS Gettysburg Hospital Primary Stroke Center Gettysburg 17325 CARBON Gnadden Huetten Memorial -

Graduate Medical Education at Westchester Medical Center About Our Residency and Fellowship Programs at Westchester Medical Center

Graduate Medical Education at Westchester Medical Center About our Residency and Fellowship Programs at Westchester Medical Center Westchester Medical Center (WMC), as a regional healthcare referral center, provides high-quality, advanced tertiary and quaternary health services to the people of New York’s Hudson Valley. The Westchester Medical Center has a long-standing record as an academic medical center committed to education and research. Through its academic medical center activities, WMC provides cutting edge care to its patients, while preparing future generations of care givers in an interdisciplinary and interprofessional clinical learning environment. As an ACGME accredited Sponsoring Institution and in affiliation with New York Medical College as well as WMCHealth System member institutions, our residency and fellowship programs enjoy an integrated clinical and academic education platform that provides health care services for over three million adults and children in the Hudson Valley Region. Westchester Medical Center Specialty and Subspecialty training programs include 495 residents and fellows as well as 555 core clinical faculty who serve as the foundation of our clinical and scholastic enterprise. As a Sponsoring Institution as well as Participating Site, Westchester Medical Center supports the clinical learning environment of the following residency and fellowship experiences: Internal Medicine Residency Pediatric Residency Fellowships Fellowships Cardiovascular Disease Pediatric Gastroenterology Interventional Cardiology -

Problems and Countermeasures in the Network Construction of Private Hospital Shuchen Liu Southeast University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China, 211189 [email protected]

International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2015) Problems and Countermeasures in the Network Construction of Private Hospital Shuchen Liu Southeast University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China, 211189 [email protected] Keywords: Network construction, Civilian-run hospital private hospital, Problems , Countermeas- ures. Abstract. Network construction does not constitute a difficulty in public hospitals in China. But it is a headache for the civilian -run hospitals. Compared with the governmental hospital, the civilian- run hospital is in a disadvantageous position in finance, technology and talents. Due to the compre- hensive disadvantages, the network construction in civilian-run hospital also falls behind that of governmental hospital. This paper analyzes the problems of network construction in private hospital and puts forward the corresponding measures in order to provide some references for the related researches. Concept of Private Hospital Civilian-run hospitals are the medical institutions that are funded by social capital and approved by the administrative department of public health. The biggest characteristic of civilian-run hospital is self-supporting, self-management, self-development and self-perfection. This kind of hospital be- longs to private hospitals in foreign countries. At present, China's civilian-run hospitals are basically equivalent to private hospitals, so it is also known as private hospitals for civilian-run hospitals. China has made many policies to encourage and support social capital to enter the medical field, and promote the diversification of investment subjects in medical institutions, and provide the basic guarantee for the development of private hospitals at the policy level. But there are still many prob- lems in private hospitals, such as: the degree of social credibility needs to be further improved, the medical personnel should be strengthened, the regulations need to be perfected, and the fund is gen- erally insufficient.