Third-Party Beneficiaries and Contractual Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlanta Broadcast Television Channel Line-Up

ATLANTA BROADCAST TELEVISION CHANNEL LINE-UP Display RF ChannelP.S.I.P. ID Network/Programming Broadcasting Antenna Tower Location City Of License (if not Atlanta) 2.1 39.1 WSB-HD ABC Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 2.2 39.2 WSB-SD Me TV Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 4 x WUVM-LP Azteca America North Druid Hills Atlanta, GA 5.1 27.3 WAGA-HD FOX North Druid Hills Atlanta, GA 7.1 7.3 WCIQ-DT PBS (Alabama Public Television) Mt. Cheaha, AL Cheaha Mountain, AL 7.2 7.4 WCIQ-D1 PBS World Mt. Cheaha, AL Cheaha Mountain, AL 7.3 7.5 WCIQ-D2 Create TV Mt. Cheaha, AL Cheaha Mountain, AL 8.1 8.1 GPB HD PBS (Georgia Public Broadcasting) Stone Mountain Athens/Atlanta, GA 8.2 8.2 Kids PBS Kids Stone Mountain Athens/Atlanta, GA 8.3 8.3 Knowled PBS World / GPB Knowledge Stone Mountain Athens/Atlanta, GA 11.1 10.3 WXIA-TV NBC Arizona Avenue Atlanta, GA 11.2 10,4 WXIA-WX 11Alive WIZtv powered by Accuweather Arizona Avenue Atlanta, GA 14.1 51.3 ION Ion Bear Mountain Rome, GA 14.2 51.4 qubo Qubo Bear Mountain Rome, GA 14.3 51.5 IONLife Ion Life Bear Mountain Rome, GA 14.4 51.6 ShopTV ShopTV (Infomercials) Bear Mountain Rome, GA 16.1 16.1 WYGA-LD N/A (Color Bars) Inman Park/Reynoldstown Atlanta, GA 16.2 16.2 SBN Sonlife Broadcasting Network Inman Park/Reynoldstown Atlanta, GA 16.3 16.3 PunchTV Punch TV Network Inman Park/Reynoldstown Atlanta, GA 16.4 16.4 WYGA-LD N/A (Color Bars) Inman Park/Reynoldstown Atlanta, GA 16.5 16.5 PeaceTV Peace TV (Islamic) Inman Park/Reynoldstown Atlanta, GA 16.6 16.6 M Canal N/A (Color Bars) Inman Park/Reynoldstown Atlanta, GA 17.1 20.3 WPCH-DT Peachtree TV North Druid Hills Atlanta, GA 18.1 33.1 WNGH-DT PBS (Georgia Public Broadcasting) Chatsworth, GA Chatsworth/Dalton, GA 18.2 33.2 Kids PBS Kids Chatsworth, GA Chatsworth/Dalton, GA 18.3 33.3 Knowled PBS World / GPB Knowledge Chatsworth, GA Chatsworth/Dalton, GA 22.1 22.1 WSKC-CD Fuxion TV (African/Caribbean) Satelite Blvd. -

Fred Residential 1111.Indd

COX TV STARTER (ELM) COX TV ESSENTIAL COX ADVANCED TV (ELM) PAY-PER-VIEW (PPV) SPORTS & INFORMATION PAK LATINO PAK (ELM) INTERNATIONAL COX TV STARTER COX PLUS PACKAGE SPORTS & INFORMATION PAK November 2011 PREMIUM CHANNELS* HIGH DEFINITION* HIGH DEFINITION*‡ HIGH DEFINITION* 2 WDCA 20 (My20) Includes all the channels from the Digital Music Choice Digital Pay-Per-View (PPV) 241 VERSUS 400 Disneyyp XD Español SAP 3 WETA 26 (PBS) 242 Fox Soccer ELM 401 Discoveryy en Español 279 Saigong Broadcasting 1002 MyNetwork TV HD (WDCA) ELM HBO 1241 VERSUS HD COX TV STARTER package. 900 SWRV (requires Variety Pak) 500 IN DEMAND Preview Channel 402 MTV TR3S Television Network 4 WRC 4 (NBC) 501–502 Pay-Per-View Events 244 ESPN Classic 1003 PBS (WETA) HD ELM 1301 HBO Comedy HD (East Coast) 1242 Fox Soccer HD ELM 36 E! Entertainment Television ELM 901 Hit List 404 CNN en Españolp 281 TFC (The Filipino Channel) 5 WTTG 5 (FOX) 902 Hip-Hop and R&B 590 Playboy & Playboy TV Adult PPV 245 ESPNews 405 Fox Deportesp 282 GMA Pinoy (Filipino) 1004 NBC HD (WRC) ELM 1302 HBO Zone HD (East Coast) 1245 ESPNews HD 37 BET 1303 HBO Signature HD (East Coast) 6 WTVR 6 (CBS) 903 MC MixTape 591 TEN Adult PPV 246 ESPNU 406 Boomerang Español SAP 284 CTI Zhongg Tian Channel (Chinese) 1005 FOX HD (WTTG) ELM 1246 ESPNU HD 38 The Disney Channel CFP ELM 592 Vavoom Adult PPV 407 Canal Sur 285 Phoenix North America 1305 HBO Family HD (East Coast) 1247 NBA TV HD 7 WJLA 7 (ABC) 904 Dance/Electronica 247 NBA TV 1007 ABC HD (WJLA) ELM 39 The Weather Channel 593 Club Jenna Adult PPV 248 -

One Page Summary of Written Statement of Patricia Jo Boyers

One Page Summary of Written Statement of Patricia Jo Boyers President and Vice Chairman of the Board of BOYCOM VISION and Vice Chairman of ACA Connects – America’s Communications Association Before the House Energy and Commerce Committee Subcommittee on Communications and Technology “STELAR Review: Protecting Consumers in an Evolving Media Marketplace” I helped found BOYCOM VISION, a small cable system in the Ozark Mountains, in 1992. You’re going to hear a lot today about the amazing things going on in the evolving media marketplace. But I’d like to tell you about how things look from my corner of southeast Missouri. I’d like to focus in particular on “retransmission consent” agreements between companies like mine and television stations. If you were around the last time Congress considered satellite legislation, you heard us talk about double-digit increases, blackouts, and forced carriage of junk channels. This still happens today. And it’s a far cry from what Congress expected when it created a special rule in reliance on NAB’s promises that prices wouldn’t go up and that any fees would stay with the local station. Recent changes in the marketplace, however, have made things far worse. First, individual broadcasters now control multiple “top-four” network feeds in more than a hundred local markets – and sometimes control three or even four such feeds – despite FCC rules that are supposed to prevent this kind of anti-consumer consolidation. Second, broadcasters have gotten much bigger nationally, with behemoths like Sinclair and Nexstar controlling more than one hundred stations across the country. -

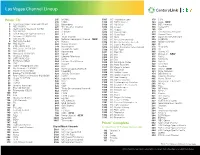

Las Vegas Channel Lineup

Las Vegas Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 215 MSNBC 5107 MC Throwback Jamz 173 GSN 216 CNBC 5108 MC R&B Classics 184 Logo NEW 2 City of Las Vegas Television (KCLV) 222 Bloomberg 5109 MC R&B Soul 188 BBC America 3 NBC (KSNV) 225 The Weather Channel 5110 MC Gospel 189 Current TV 4 Clark County Television (CCTV) 230 C-SPAN 5111 MC Reggae 195 ION 5 FOX (KVVU) 231 C-SPAN2 5112 MC Classic Rock 211 Fox Business Network 6 FOX 5 Weather 24/7 (KVVU-D2) 251 TLC 5113 MC Retro Rock 253 Animal Planet 7 Antenna TV (KSNV-D3) 255 Travel Channel 5114 MC Rock 257 Oprah Winfrey Network 8 CBS (KLAS) 266 National Geographic Channel NEW 5115 MC Metal (uncensored) 258 SCIENCE 9 MeTV (KLAS-D2) 271 History 5116 MC Alternative (uncensored) 259 Military Channel 10 PBS (KLVX) 303 Disney Channel 5117 MC Classic Alternative 260 ID 11 V-Me (KLVX-D3) 314 Nickelodeon 5118 MC Adult Alternative (uncensored) 272 Biography 12 PBS Create (KLVX-D2) 326 Cartoon Network 5120 MC Soft Rock 274 H2 13 ABC (KTNV) 327 Boomerang 5121 MC Pop Hits 305 Disney XD 14 Mexicanal (KTNV-D2) 337 Sprout 5122 MC 90s 307 Disney Jr. NEW 15 Univision (KINC) 361 Lifetime Television 5123 MC 80s 315 Nick 2 16 LATV (KINC-D2) 362 LMN 5124 MC 70s 316 Nicktoons 17 Telefutura (KELV) 364 Lifetime Real Women 5125 MC Solid Gold Oldies 320 Nick Jr. 18 QVC 368 Oxygen 5126 MC Party Favorites 322 Teen Nick 19 Home Shopping Network 420 QVC 335 The Hub 21 My Network TV (KVMY) 5127 MC Stage & Screen 422 Home Shopping Network 5128 MC Kids Only! 373 WE tv NEW 22 Movies+ (KGNG-D5) 424 ShopNBC 381 Style Network 23 Bounce TV (KGNG-D3) -

Federal Communications Commission DA 09-1316 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter O

Federal Communications Commission DA 09-1316 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Cox Communications Las Vegas, Inc. ) ) CSR-8125-A For Modification of the Las Vegas, Nevada ) DMA ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: June 11, 2009 Released: June 12, 2009 By the Senior Deputy Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau: I. INTRODUCTION 1. Cox Communications Las Vegas, Inc. (“Cox”), filed the above-captioned petition for special relief seeking to modify the Las Vegas, Nevada designated market area (“DMA”) with respect to television broadcast station KEGS (Ind., Ch. 7), Goldfield, Nevada (“KEGS”). We note that, while KEGS’ city of license is physically located in the Reno, Nevada DMA, Nielsen has assigned the station to the Las Vegas DMA. Specifically, Cox requests that KEGS be excluded, for purposes of the cable television mandatory broadcast signal carriage rules, from communities it serves which are located in Clark County, Nevada.1 An opposition to this petition was filed on behalf of Nevada Channel 3, Inc., Debtor-in-Possession, licensee of KEGS, to which Cox replied. For the reasons stated below, we grant Cox’s request. II. BACKGROUND 2. Pursuant to Section 614 of the Communications Act and implementing rules adopted by the Commission, commercial television broadcast stations are entitled to assert mandatory carriage rights on cable systems located within the station’s market.2 A station’s market for this purpose is its “designated market area,” or DMA, as defined by Nielsen Media Research.3 A DMA is a geographic market designation that defines each television market exclusive of others, based on measured viewing patterns. -

Television YEARBOOK® 2015

Television YEARBOOK® 2015 Also available on CD ROM and via the Internet through BIA/Kelsey’s MEDIA Access Pro™ BIA /Kelsey • 15120 Enterprise Ct., Chantilly, VA 20151-1217 Phone: 703-818-2425 • Fax: 703-803-3299 • E-mail: [email protected] • Web: www.biakelsey.com BIA/Kelsey’s Television Yearbook® 2015 Copyright © 2015 BIA Advisory Services, LLC Thomas J. Buono, Publisher BIA/Kelsey • 15120 Enterprise Ct., Chantilly, VA 20151-1217 Phone: 703-818-2425 • Fax: 703-803-3299 • E-mail: [email protected] • Web: www.biakelsey.com Table of Contents Copyrights and Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iv United States Overview ......................................................................................................................... v Sample Market ...................................................................................................................................... vi Market Overview Key ........................................................................................................................... vii Keys & Codes ......................................................................................................................................viii Market Section (Alphabetical Order) ...........................................................................................................1 Group Owners .........................................................................................................................................235 -

Comcast Channel Lineup

Sattec Inc. 404-396-8998 (Direct) Trust only the Pro with your TV! 719 W. Lanier Ave. Suite B 404-935-6171 (Office) Fayetteville, GA 30214 Boomerang VH1 Classic Rock On MLB Network Sample Channel Line Up- Atlanta WOM Channel Lineup CBS College Sports VH1 Soul MLB Network HD ^ LIMITED BASIC FEARnet On CBS College Sports HD ^ WE On NBA TV On Access # Food HD ^ On Centric WE HD ^ On NBA TV HD ^ HSN Food Network On CMT Pure Country Weatherscan NFL Network On NBC WeatherPlus # (WXIA) Fox News CNN International DIGITAL PREMIUM NFL Network HD ^ QVC Fox News HD ^ Cooking Channel α Cinemax On NFL RedZone Retro Television Network # (WSB-DT) Fox Sports Net Current TV 5StarMax On NFL RedZone HD ^ TV Guide Network# On FOX Sports South HD ^ Discovery Health On 5Star Max HD ^ On NHL Network On Universal Sports (WXIA) FX On Discovery Kids On Action Max On NHL Network HD ^ On WAGA (FOX 5) Atlanta FX HD ^ On Disney XD On Action Max HD ^ On Outdoor Channel WAGA (FOX) HD ^ G4 On Disney XD HD ^ CCTV-4 Tennis Channel WATC (Ind. 57) Atlanta G4 HD ^ On DIY Cinemax (East) On MUSIC CHOICE WATL (My Network) HD^ Golf Channel On Encore On Cinemax (West) On 46 Channels of Digital Music WDTA (Daystar) # Golf HD ^ Encore Action On Cinemax HD ^ On FAMILY TIER WGCL (CBS 46) Atlanta On Hallmark Encore Drama On CTI-Zhong Tian C-SPAN WGCL (CBS) HD^ On Hallmark Movie Channel HD ^ Encore HD ^ On HBO (East) On C-SPAN2 WGN (Ind. 9) Chicago Hallmark Movie Channel Encore Love On HBO (West) On Discovery Kids WGN America HD^ Hallmark Movie Channel Encore Mystery On HBO 2 On Disney -

NAB Comments Re: FCC Examination of the Future of Media

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Examination of the Future of Media and ) GN Docket No. 10-25 Information Needs of Communities in a Digital ) Age ) To: The Commission COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCASTERS Jane E. Mago Jerianne Timmerman Scott A. Goodwin NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCASTERS 1771 N Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 429-5430 May 7, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................iii I. BROADCASTING PLAYS A UNIQUE, CRITICAL, AND OFTEN LIFE- SAVING ROLE IN PROVIDING AMERICANS WITH NEWS AND INFORMATION............................................................................................................... 2 A. Broadcast Television And Radio Remain The Only Free, Trusted Sources Of Information And News Available To All Americans..................... 2 B. Broadcasting Is Designed, And Continues To Operate, To Collectively Serve The Interests Of Communities Across The Country, Reflecting Local Values And Interests. ................................................................................. 8 C. Broadcasting Is The Most Important Source For Critical, Life-Saving Emergency Journalism....................................................................................... 14 D. Broadcast Stations Are Embracing Digital Technologies To Better Adapt To Changes In Consumer Behavior And To Enhance Local News. ................................................................................................................... -

United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ______

United States Court of Appeals For the Eighth Circuit ___________________________ No. 12-1287 ___________________________ Retro Television Network, Inc. lllllllllllllllllllll Plaintiff - Appellant v. Luken Communications, LLC; Retro Television, Inc., formerly known as Retro Programming Services, Inc. lllllllllllllllllllll Defendants - Appellees ___________________________ No. 12-1838 ___________________________ Retro Television Network, Inc. lllllllllllllllllllll Plaintiff - Appellant v. Luken Communications, LLC; Retro Television, Inc., formerly known as Retro Programming Services, Inc. lllllllllllllllllllll Defendants - Appellees ____________ Appeal from United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas - Little Rock ____________ Appellate Case: 12-1287 Page: 1 Date Filed: 10/17/2012 Entry ID: 3964607 Submitted: September 20, 2012 Filed: October 17, 2012 ____________ Before WOLLMAN, BEAM, and MURPHY, Circuit Judges. ____________ WOLLMAN, Circuit Judge. Retro Television Network, Inc., appeals the district court’s1 dismissal of its claims against Luken Communications, LLC and Retro Television, Inc. (collectively Appellees) under Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Retro Television Network, Inc. appeals also the district court’s adverse award of attorneys’ fees. We affirm. I. In December 2005, Equity Broadcasting Corporation (Equity) entered into an intellectual property agreement (IPA) with Retro Television Network, Inc. The IPA’s recitals explained that Equity desired to acquire Retro Television Network, Inc.’s noncreative rights in Retro Television Network for the purpose of developing a national broadcast network. To accomplish this, Retro Television Network, Inc. agreed to transfer its noncreative rights in Retro Television Network to one of Equity’s subsidiaries. In exchange for this transfer, Equity agreed to pay Retro Television Network, Inc. royalty payments in the amount of ten percent of the net revenue of Retro Television Network. -

Televisión Digital Terrestre En Europa Y Estados Unidos: Una Comparativa Entre Modelos De Negocio

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad I TELEVISIÓN DIGITAL TERRESTRE EN EUROPA Y ESTADOS UNIDOS: UNA COMPARATIVA ENTRE MODELOS DE NEGOCIO. MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Raquel Urquiza García Bajo la dirección del doctor Enrique Bustamante Ramírez Madrid, 2009 • ISBN: 978-84-692-7629-7 TESIS DOCTORAL “TELEVISIÓN DIGITAL TERRESTRE EN EUROPA Y ESTADOS UNIDOS: UNA COMPARATIVA ENTRE MODELOS DE NEGOCIO” 2 2 Televisión Digital Terrestre en Europa y Estados Unidos: una comparativa entre modelos de negocio Realizada por: Raquel Urquiza García Dirigida por: Dr. Enrique Bustamante Ramírez Departameto CAVP I, Universidad Complutense de Madrid 10 de septiembre de 2008 Raquel Urquiza García - 3 4 4 Televisión Digital Terrestre en Europa y Estados Unidos: una comparativa entre modelos de negocio A Enrique Bustamante, por su confianza e impulso intelectual a lo largo de estos últimos años; a mis padres y hermanos, apoyo insustituible; a todas aquellas personas que han seguido con interés y cariño cada uno de los pasos que he dado en mi carrera académica. Raquel Urquiza García - 5 6 6 Televisión Digital Terrestre en Europa y Estados Unidos: una comparativa entre modelos de negocio Índice Índice .................................................................................................................................. 5 Palabras Claves ............................................................................................................... -

How to Order How It Works Time Warner Cable Contact Information

Digital Packages Premium Services Video On Demand/ Digital Choice $5.95/mo All services require digital set-top equipment. Pay-Per-View/ Digital Variety $10.95/mo HBO $14.99/mo* TWC Digital Movie Pass $10.95/mo Subscription Services Cinemax $12.99/mo* TWC Digital Sports Pass $5.95/mo Showtime $12.99/mo* All services require digital set-top equipment. TWC 3D Pass $10.00/mo The Movie Channel $12.99/mo* HD Plus $6.95/mo Movies On Demand $.99 – $14.99 ea Starz $12.99/mo* Nuestra Tele $4.95/mo Howard TV On Demand $13.99/mo Flix (Mini Premium A La Carte) $1.95/mo here! $6.99/mo Digital Sports Packages ART (Arabic) $9.95/mo Too Much For TV On Demand $14.99/mo Channel One Russia $14.95/mo Call for pricing Disney Family Movies RAI Italia $9.95/mo On Demand $4.99/mo Equipment RTN (Russia) $14.95/mo iNDEMANDSM Pay-Per-View The Filipino Channel $9.95/mo Special Events Prices vary Digital, HDTV or DVR Converter TV Asia (South Asian) $14.95/mo and Remote Control $8.95/mo TV5MONDE (French) $9.95/mo CableCARD™ $2.00/mo TV Japan $24.95/mo Digital Video Recorder Service $10.95/mo Zee TV (Indian) $14.95/mo *Includes the corresponding Premium Channel On Demand service. What’s available as How to order Time Warner Cable an optional upgrade: Call (800) 934-4181 and select menu option 2. Contact Information • Digital Video Recorder (DVR) You will need to provide your address, telephone Sales Office number and one of the following identification (800) 934-4181; select option 2 • No‑fee HD channels numbers: Social Security number or driver’s 24-hour Customer Care • Hundreds of Digital TV channels license number. -

Raleigh Channel Lineup

Raleigh Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 222 Bloomberg 9999 DVR 5144 Pop Latino 225 The Weather Channel Digital Music Channels 5145 Tropicales 5 CBS 230 C-SPAN 5146 Mexicana 6 This TV 231 C-SPAN2 5101 Hit List 5147 Romances 8 QVC 250 TLC 5102 Hip Hop & R&B 9 Home Shopping Network 254 Travel Channel 5103 Mix Tape PrismTM Complete 11 ABC 5104 Dance/Electronica 265 National Geographic Channel TM Includes Prism TV Package channels, plus 12 Live Well 270 History 5105 Rap (uncensored) 17 NBC 302 Disney Channel 5106 Hip Hop Classics 132 American Life 18 Universal Sports 314 Nickelodeon 5107 Throwback Jamz 148 G4 22 CW 325 Cartoon Network 5108 R&B Classics 153 Chiller 26 ESPN 327 Boomerang 5109 R&B Soul 157 TV One 27 ESPN2 337 Sprout 5110 Gospel 161 Sleuth 28 MyNetworkTV 360 Lifetime Television 5111 Reggae 173 GSN 30 Tri-state Christian Television 362 Lifetime Movie Network 5112 Classic Rock 188 BBC America 36 UNC PBS 364 Lifetime Real Women 5113 Retro Rock 189 Current TV 37 UNC – KD 367 Oxygen 5114 Rock 252 Animal Planet 38 UNC – EX 420 QVC 5115 Metal (uncensored) 256 Oprah Winfrey Network 47 ION 422 Home Shopping Network 5116 Alternative (uncensored) 258 Science Channel 50 FOX 424 ShopNBC 5117 Classic Alternative 259 Military Channel 51 Retro Television Network 428 Jewelry Television 5118 Adult Alternative (uncensored) 260 ID 108 TNT 450 HGTV 5120 Soft Rock 272 Biography 112 TBS 452 Food Network 5121 Pop Hits 274 History International 120 Discovery Channel 502 MTV 5122 90s 304 Disney XD 124 USA Network 518 VH1 5123 80s 315 Nick Too 128 FX 525 CMT 5124 70s 316 Nicktoons 134 E! 560 Trinity Broadcasting Network 5125 Solid Gold Oldies 320 Nick Jr.