Fran Collyer Jim Mcmaster Roger Wettenhall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the Proceedings Legislative

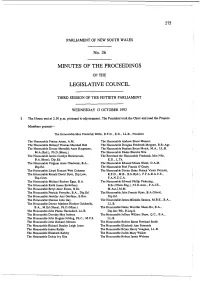

PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES No. 26 MINUTES OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL THIRD SESSION OF THE FIlTIETH PARLIAMENT WEDNESDAY 13 OCTOBER 1993 1 The House met at 2.30 p.m. pursuant to adjournment. The President took the Chair and read the Prayers. Members present- The Honourable Max Frederick Willis, R.F.D., E.D., LL.B., President The Honourable Franca Arena, A.M. The Honourable Andrew Bruce Manson The Honourable Richard Thomas Marshall Bull The Honourable Douglas Frederick Moppett, B.Sc.Agr. The Honourable Doctor Meredith Anne Burgmann, The Honourable Stephen Bruce Mutch. M.A.. LL.B. M.A.(Syd.). Ph.D.(Macq.) The Honourable Elaine Blanche Nile The Honourable Janice Carolyn Bumswoods. The Revcrend the Honourable Frederick John Nile, B.A.(Hons), Dip.Ed. E.D., L.Th. The Honourable Virginia Anne Chadwick, B.A.. The Honourable Edward Moses Obeid, O.A.M. Dip.Ed. The Honourable Paul Francis O'Grady The Honourable Lloyd Duncan Watt Coleman The Honourable Doctor Brian Patrick Victor Peuutti. The Honourable Ronald David Dyer. Dip.Law, R.F.D.. M.B.. B.S.(Syd.), F.F.A.R.A.C.S.. Dip.Crim. F.A.N.Z.C.A. The Honourable Michael Rueben Egan, B.A. The Honourable Edward Philip Pickering, The Honourable Keith James Enderbury B.Sc.(Chem.Ene.).- ,. F.I.E.Aus1.. F.A.I.E., The Honourable Beryl Alice Evans, B.Ec. M.Aus.1.M.M. The Honourable Patricia Forsythe. B.A., Dip.Ed. The Honourable John Francis Ryan, B.A.(Hons). The Honourable Jennifer Ann Gardiner, B.Bus. -

Planning Controls and Sustainability

Planning controls and sustainability PlanFirst’s potential seen through a case study of Pittwater 21 Do local plans written using the principles contained in Plan First contribute to improving ecologically sustainable development? An Australian perspective on the sustainability impacts of the interaction between planning and building design. By Richard James Clarke A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Sustainable Futures Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology, Sydney June 2006 i Certificate of authorship and originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate: ………………………………………………………………………………… Richard James Clarke Dated this ……………….. day of …………………….. 2006. ii Table of contents CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP AND ORIGINALITY................................................................. II LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... VII LIST OF TABLES......................................................................................................................... VII ABSTRACT................................................................................................................................ -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

The Politics of Bail Reform: the New South Wales Bail Act, 1976–2013

1 THE POLITICS OF BAIL REFORM: THE NEW SOUTH WALES BAIL ACT, 1976–2013 MAXWELL FRANCIS TAYLOR Bachelor of Arts (University of NSW), Bachelor of Laws (University of NSW), Bachelor of Arts (Honours) (Macquarie University) Macquarie University Law School 9 October 2013 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 STATEMENT: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 10 1.2 Background …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 1.3 Research Question ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 15 1.4 Methodology ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 18 1.5 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 26 1.5.1 Literature on the big picture crisis …………………………………………………………………. 26 1.5.2 Literature considering the right to bail and the erosion of the presumption in favour of bail …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 27 1.5.3 Literature concerning the effects of bail laws and other changes to bail law on disadvantaged and indigenous accused …………………………………………….. 33 1.5.4 Literature considering the role of the media in bringing about changes to bail law …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 35 1.5.5 Literature considering public attitudes …………………………………………………………. 37 1.6 Chapter outline ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 38 CHAPTER 2. THE IMPORTANCE OF BAIL AND THE HISTORY OF BAIL IN ENGLAND AND NEW SOUTH -

NSW By-Elections 1965-2005

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE New South Wales By-elections, 1965 - 2005 by Antony Green Background Paper No 3/05 ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 0 7313 1786 6 September 2005 The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the New South Wales Parliamentary Library. © 2005 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, with the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. New South Wales By-elections, 1965 - 2005 by Antony Green NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE David Clune (MA, PhD, Dip Lib), Manager..............................................(02) 9230 2484 Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law .........................(02) 9230 2356 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ......................(02) 9230 2768 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Research Officer, Law ...................................(02) 9230 3085 Stewart Smith (BSc (Hons), MELGL), Research Officer, Environment ...(02) 9230 2798 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics.......................(02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/WEB_FEED/PHWebContent.nsf/PHPages/LibraryPublications Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. -

Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 1992

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES Annual Report 1991-92 Report No. 66 November 1992 This publication has been catalogued in the New South Wales Parliamentary Library as follows: New South Wales. Parliament. Public Accounts Committee Annual report, 1991-92 /Public Accounts Committee, Parliament of New South Wales - [Sydney, NSW]: Public Accounts Committee, 1992 - 58 p. : 34 cm (Report / Public Accounts Committee, Parliament of New South Wales; no. 66) 1. New South Wales. Parliament. Public Accounts Committee 2. Expenditures, Public - New South Wales 1. Title Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Public Accounts Committee. Report; no. 66 328.3658 ISSN 1037-3829 Annual Report for 1991-92 CONTENTS MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE................................ ....................................................2 CHAIRMAN'S FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................5 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR ...................................................................................................................................7 CHARTER ........................................................................'. ........................................................................................8 CORPORATE PLAN................................ ....................................... .............................................................................. 10 Mission statement ........................................................................................................................................10 -

Australian Association Doctors in Developmental Disability Medicine

Australian Association of Developmental Disability Medicine Inc. 8 May 2011 Productivity Commission Australian Government RE: Disability Care and Support Public inquiry The Australian Association of Developmental Disability Medicine (AADDM) is a national organisation of medical practitioners who are committed to improving health outcomes for people with intellectual disability. The members of the association provide clinical medical services directly to people (children, adolescents and adults) with intellectual disability, as well as research, education and policy advice to government. We would like to provide the following submission to the productivity commission. Please also find as attachments a recent AADDM proposition of the Place of People with Intellectual Disability in Mental Health Reform and an AADDM position statement on the Health of People with Intellectual Disabilities. AADDM strongly supports a review of the long term disability care and support scheme. We agree that the current system is fragmented, underfunded and unpredictable. Parents and carers often feel frustrated and extremely concerned about the future welfare of their child. We commend the Australian Government on rising to the challenge of improving this system to better support people with intellectual disabilities. We would like to emphasise the following issues and concerns; 1. The quality of life of people with intellectual disability is dependent on an acceptable level of general physical and mental health. Current evidence highlights major inequities in access to health services and health outcomes. 2. Improving health services is a cornerstone of improving health outcomes, and this system must involve an effectively integrated primary and specialist health care network for both physical and mental health. -

Australasian Parliamentary Review Autumn 2013, Vol. 28, No. 1

Australasian Parliamentary Review Autumn 2013, Vol. 28, No. 1 FROM YOUR EDITOR Jennifer Aldred 1 ARTICLES 3 Race and the Australian Constitution George Williams 4 The dilemmas of drafting a Constitution for a new state Anne Twomey 17 Arm’s length bodies in the Australian Capital Territory — time for review? Roger Wettenhall 25 # Understanding conscience vote decisions: the case of the ACT Peter Balint and Cheryl Moir 43 # Committees in a unicameral parliament: impact of a majority government on the ACT Legislative Assembly committee system Grace Concannon 57 Guarding MPs’ integrity in the UK and Australia David Solomon 71 Unproclaimed legislation — the delegation of legislative power to the executive Alex Stedman 83 # Through the lens of accountability: referral of inquiries by ministers to upper house committees Merrin Thompson 97 # Strengthening parliaments in nascent democracies: the need to prioritize legislative reforms Abel Kinyondo 109 _________________________ # These papers have been double blind reviewed to academic standards. PARLIAMENTARY CHRONICLES 125 Electoral law and the campaign trail Harry Phillips 126 ‘From the Tables’ A round-up of administrative and procedural developments in the Australasian Parliaments — Robyn Smith 130 BOOK REVIEWS 139 Anne Twomey: Reluctant Democrat — Sir William Denison in Australia 1847–1861 140 Mary Crawford: Tales from the Political Trenches 143 David Clune: • Politics, Society, Self & • What is to be Done?: The struggle for the soul of the labour movement 146 Kevin Rozzoli: The Australian Policy Handbook: Fifth Edition 149 © Australasian Study of Parliament Group. Requests for permission to reproduce material from Australasian Parliamentary Review should be directed to the Editor. ISSN 1447-9125 FROM YOUR EDITOR Jennifer Aldred This issue carries three articles on various topics dealing with governance in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT).