The Military Chaplains' Review Is Published Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g15z7t No online items Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 Finding aid prepared by Performing Arts Special Collections Staff; additions processed by Peggy Alexander; machine readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 PASC 353 1 Title: Roy Huggins papers Collection number: PASC 353 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Physical Description: 20 linear ft.(58 boxes) Date: 1948-2002 Abstract: Papers belonging to the novelist, blacklisted film and television writer, producer and production manager, Roy Huggins. The collection is in the midst of being processed. The finding aid will be updated periodically. Creator: Huggins, Roy 1914-2002 Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

St. Ives by Robert Louis Stevenson

St. Ives By Robert Louis Stevenson 1 The following tale was taken down from Mr. Stevenson’s dictation by his stepdaughter and amanuensis, Mrs. Strong, at intervals between January 1893 and October 1894 (see Vailima Letters, pp. 242–246, 299, 324 and 350). About six weeks before his death he laid the story aside to take up Weir of Hermiston. The thirty chapters of St. Ives which he had written (the last few of them apparently unrevised) brought the tale within sight of its conclusion, and the intended course of the remainder was known in outline to Mrs. Strong. For the benefit of those readers who do not like a story to be left unfinished, the delicate task of supplying the missing chapters has been entrusted to Mr. Quiller-Couch, whose work begins at Chap. XXXI. {0} [S. C.] 2 CHAPTER I—A TALE OF A LION RAMPANT It was in the month of May 1813 that I was so unlucky as to fall at last into the hands of the enemy. My knowledge of the English language had marked me out for a certain employment. Though I cannot conceive a soldier refusing to incur the risk, yet to be hanged for a spy is a disgusting business; and I was relieved to be held a prisoner of war. Into the Castle of Edinburgh, standing in the midst of that city on the summit of an extraordinary rock, I was cast with several hundred fellow-sufferers, all privates like myself, and the more part of them, by an accident, very ignorant, plain fellows. -

Understanding and Helping the Grieving Child Safe Crossings - a Program for Grieving Children at Providence Hospice of Seattle

Understanding and helping the Grieving Child Safe Crossings - A Program for Grieving Children at Providence Hospice of Seattle Each of us will face the death of a significant person at some time. We seek other people, books, counseling or other outlets for support during the grief process. But who helps a child deal with a death or an impending death of someone they care about? Naturally children turn to other significant persons – family, friends, neighbors, relatives, and teachers. Although children may understand and respond to terminal illness and to death differently than adults, helping the grieving child is not that different from helping the grieving adult. Your interaction can have an important impact in helping the child deal with a significant person’s terminal illness and death in a healthy way. Here are some insights and suggestions GENERAL FACTORS Children grieve as part of a family. When someone is diagnosed with a terminal illness, it affects the way in which the entire family functions. Roles and responsibilities will adjust to accommodate new needs in your family. In addition to grieving the illness of a significant person, your children will also grieve the many small and large changes that follow, such as: Changes in daily routine Decreased emotional availability of adult caregivers Increased individual responsibilities within the family Changes in the ability of the sick person to interact as they have in the past Children re-grieve. Caregivers often express surprise when their children shift from “being fine” to having difficulties in school or relationships as a result of the illness or death. -

Father's Stories

“Beauty is not who you are on the outside, it is the wisdom and time you gave away to save another struggling soul, like you.” ~ Shannon L. Alder A Tale of Our Fathers 1976: Vincent and Father… “You shouldn’t waste your time on an old man like me…” Father turned his head aside to smother a racking cough with a scrap of cloth. “I’m past worrying about. Just leave me be and let me die in peace.” “You are most certainly not going to die. But you have never made the easiest of patients, Father,” Vincent reminded him gently as he carefully raised the older man’s head to feed him the last spoonful of soup from the bowl beside the bed. “You always take care of us when we are sick. Now it’s our turn to look after you. So lie still and regain your strength. The worst is over.” “I guess so. But I don’t like feeling so weak and helpless.” Father lay back fretfully against the pillows and closed one eye to focus on his son better. “You really do make one heck of a nursemaid, Vincent. I’ll give you that.” He chuckled weakly. “But I guess it takes a lot of courage — more than I have right now — to say no to you, when your mind’s made up to something. I didn’t fancy dying just yet, anyway.” He rolled his head to glance at his other carer. “What do you say, Mary? Did we do a good job with raising our boy here?” “I think we did just fine.” Mary smiled, looking up from wringing out a cloth over a wooden bowl. -

Purloined Letter (Part One)

FROM THE BAG We’ll always have Paris. Rick Blaine CasaBlanca (1942) pictured: The Eiffel Tower, as seen from Trocadéro Palace during the Paris Exposition in 1889. THE PURLOINED LETTER (PART ONE) Edgar A. Poe† Lawyers should read this old but still accessible detective story for three reasons, at least. First, while it is often cited by legal writers – practitioners, judges, scholars – for the proposition that contra- band can be hidden in plain sight, some of them seem to lack an accurate recollection of the elements of the story they are citing. We lawyers can do better than that. Second, the longstanding focus on the hidden-in-plain-sight idea has obscured the story’s citeabil- ity for other aspects of law and lawyering. Consider, for example, the anecdote of Abernethy at the end of the first part of the story. See page 91 below. It will resonate with any lawyer who has family or friends who value good legal advice but don’t do so in dollars. Third, it is a pleasure to read – it is a good tale, well told. That without more should be sufficient reason to get to know it better. The first part of the story – up to the cliffhanger – is printed here. The second part will appear in the next issue of the Green Bag. We have preserved, to the best of our abilities, the punctuation and spelling in the original. See Edgar A. Poe, The Purloined Letter, in THE GIFT: A CHRISTMAS, NEW YEAR, AND BIRTHDAY PRESENT 41- 50 (1845). A disclaimer: Republication of this ancient work does not constitute endorsement of Poe’s unkind characterization of the people of Naples – indeed, we emphatically decry it. -

Original Writing

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2005 For home--- (Original writing). Daryl Sneath University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Sneath, Daryl, "For home--- (Original writing)." (2005). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2134. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/2134 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. For home— by Daryl Sneath A Creative Writing Project Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research through English Language, Literature & Creative Writing in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2005 © 2005 -

THE Pall Mall Magazine

EDITORIAL 5( PUBLISHING OFFICES: !8,CHARiNG CROSS %L ^^t fpi?e ISailiff's dau^l^fer THE Pall Mall Magazine EDITED BY Lord Frederic HaimiltOxN Vol. XII. MAY TO AUGUST iSgy " tjivcs acquivit cunbn (g5t'(onaf ani> (puBfte^ing Offtcee i8, CHARING CROSS ROAD, LONDON, W.C. 1897 Printed by Hazell, Watson, <&= Vitwy, Ld., London and Aylesbury. " — INDEX. PAGE "Ah! Memory'' Leolinc Gi'iffiths 251 " '' Alden, W. L. A Volcanic \'alve . 409 Altson, Abbey. Illustrations to "Sleep'' 145 „ „ „ " Revocata Fides "' 433 Applin, Arthur. "Dolores." Part II 17 " ' AUBINIERE, M. AND Mme. de L'. Illustrations to Kew Gardens . 584 "Audley End." Illustrated from photographs by Rev. A. H. Alalan— Miss E. Sai'ilc 314 "August." Illustrated by W. B. Robinson .... Ada Bartrick Baker 497 Bailitfs Daughter, The.'' Coloured frontispiece by Alice Haver Facing page Baker, Ada Bartrick (A. L. Budden)- "May" . 43 " June " . 187 "July" . " Au^'ust 497 " 11 Bombay." Illustrated from photographs G. '. Forrest 545 " Bowles, Fred G. P. " Reconciliation " „ „ Moorland Reverie 70 „ „ "A Summer Idyll". 576 " Breeding Season at the Gallery on Walney Island Illustrated from photographs by Stella Hamilton . A. M. Wakefield 65 "British Army Types." ArtJiin- Jiilc Goodman— "A Subaltern, Grenadier Guards" 203 " Captain, First Life Guards " 296 "Captain, New South Wales Mounted Rifles" 466 BucKLAXD, Arthur J. Illustrations to "Orwell Hall" . 193 " ,, „ „ The Fairy Blacksmith 289 Bvles, Hounson. Illustrations to "A Fastidious Woman" 418 "Cliveden." Illustrated from photographs . Marquess of Lome, K.T., M.P. 436 Cole, H. Illustrations to "Religion". 396 „ „ „ "Pan" 416 " Colonel Drury." Illustrated by Simon Harman \'edder . John Le Breton 332 " Cornish Window, From a." With Thumb-nail Sketches by Mark Zangwill A. -

Msi9iy Bunch

afggii 1 lo EVENING EEDGEK-PHIL'EEP- Hffi SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17, TDT WHAT EVERY WOMAN WANTS TO KNOW-THI-NGS THAT INTEREST MAID AND MATRON ELLEA ADAIR'S ADVENTURES HOUSEWIFE AND PLAIN GIRL VS. PRETTY GIRL ;i , HER MARKETING She Has One Great Experience, and With It Ends The season of plenty Is bringing many Which Is the More Successful On Going Out lniA new arrivals In the vegetable world. The the Telling of the 'Vale. market show: the Business World? Large Casaba melons at 60d a break- fast luxury, J r XXX. to play. The air was called "Because It's Where Ihc mere man Is concerned, nnd Ihnt I havo elopped that, they sn(j iif special delivery letters that throw hirl Upon the vital episodes of life one finds You." Why had ho chosen such an air Srnftll bunches whllo Waldorf moro particularly the hufllness man, a of fresh joy Into such a flutter thnt she can scareeM It rather difficult to write. Yet happi- today? Its very sweetness filled the shad- celery at I5c. thing of beauty may not always be a work nt all I No, the next atenogranhnr.f 11. 111 1 ,.," ness has come lo me at last, and a great owy room with pain. forever! inI. i, no u,,,v.cl!l.. .in, l.,..- - ..1l.. g 0""5g ,, my word," cried the harassed I have quite decided on Joy that I have never known before. 1 must have sat there In the firelight, Mushrooms, varying According to size, "Upon that!" " young sales-manag- In n large ofllcc, tho There did seem somo ground n 1 30c. -

The Johnsonian April 11, 1931

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Browse all issues of the Johnsonian The oJ hnsonian 4-11-1931 The ohnsoniJ an April 11, 1931 Winthrop University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/thejohnsonian Recommended Citation Winthrop University, "The oJ hnsonian April 11, 1931" (1931). Browse all issues of the Johnsonian. 282. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/thejohnsonian/282 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The oJ hnsonian at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all issues of the Johnsonian by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TheTHE OFFICIAL PUBLICATIOJohnsoniaN OF THE STUDENT BODY OF WINTHROP COLLEGE n VOLUME VIII. NUMBER 24 ROCK HILL. SOUTH CAROLINA. SATURDAY, APRIL II. 1931 SUBSCRIPTION SI M A YEAR FACULTY CAST IN MUSIC CONTEST STUDENT GOVERNMENT GIRL SCOUT LEADERSHIP STATE HIGH SCHOOL MURDER TRIAL IS BEN 6REET PLAYERS COMEDY TONIGHT UNUSUALLY GOOD! NOMINATIONS MADE COURSE AT WINTHROP TRACK MEET STAGETODAYD AT WINTHROPi IN'TWELFTH NIGHT' "Sabine H'umrn" Will Give You a rnvillr Won Most Points. With One of Most Interesting Meetings \|ipro>lmately Filly Girls Take four Represenlatlves From Fifteen High eniors Sit as Jurors During Terrible Appreciative Audience Attends Pres- Laugh—Professors Slum Yuu Charleston and Parker School Year Held Last Evening—Elec- Offered by Miss Robertine Mc- Schools Here For Seventh An- Scene—Deep Mystery I'nrolds entation of Shakespeare's Play Something Different District Next tions to Be Held Tuesday Clendon This Week nual Track Event and Surprises Abound By Famous Troupe It's coming tonight, girls; "The Sa- 'Hie South Carolina Music Contest One of the most Interesting meetings The Girl Scout leadership course, of- Fifteen of the outstanding high "Twcnty-two states have it and we Sir Philip Ben Greet and his de- bine Women!" At eight o'clock In the "I 1831. -

The Short-Story

THE SHORT-STORY BY EDGAR ALLAN POE INTRODUCTION I DEFINITION AND DEVELOPMENT Mankind has always loved to tell stories and to listen to them. The most primitive and unlettered peoples and tribes have always shown and still show this universal characteristic. As far back as written records go we find stories; even before that time, they were handed down from remote generations by oral tradition. The wandering minstrel followed a very ancient profession. Before him was his prototype—the man with the gift of telling stories over the fire at night, perhaps at the mouth of a cave. The Greeks, who ever loved to hear some new thing, were merely typical of the ready listeners. In the course of time the story passed through many forms and many phases—the myth, e.g. The Labors of Hercules; the legend, e.g. St. George and the Dragon; the fairy tale, e.g. Cinderella; the fable, e.g. The Fox and the Grapes; the allegory, e.g. Addison's The Vision of Mirza; the parable, e.g. The Prodigal Son. Sometimes it was merely to amuse, sometimes to instruct. With this process are intimately connected famous books, such as "The Gesta Romanorum" (which, by the way, has nothing to do with the Romans) and famous writers like Boccaccio. Gradually there grew a body of rules and a technique, and men began to write about the way stories should be composed, as is seen in Aristotle's statement that a story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Definitions were made and the elements named. -

The Faith of Men 1

The Faith of Men 1 The Faith of Men The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Faith of Men, by Jack London #27-34 in our series by Jack London Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** The Faith of Men 2 *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Faith of Men by Jack London November, 1997 [Etext 1096] The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Faith of Men, by Jack London ******This file should be named fthmn10.txt or fthmn10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, fthmn11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, fthmn10a.txt. This etext was prepared by David Price, email [email protected], from the 1919 William Heinemann edition. Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. Therefore, we do NOT keep these books in compliance with any particular paper edition, usually otherwise. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. -

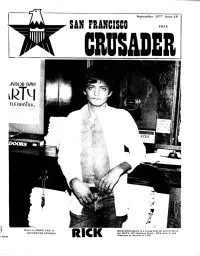

San Francisco Free Cbosader

September 1977 Issue 48 SAN FRANCISCO FREE CBOSADER -AROD DAM ÎÎ ‘ \ Photo by EDDIE VAN of RICK H O U L IH A N , is a young Iri&h lad w h o w o rk s at LT. ADVENTURE STUDIOS the HOT’L, 975 Harrison Street. Rick came to San RICK Francisco.in October of 1976. SAN FRANCISCO CRUSADER ^ COURTS SOFT ON CRIMINALS!!” NEWS District Attorney“A Coward” Districtir^k ■ ««A** « ^ AttorneyB « JosephT —. Frietas Judge ALBERT C. WOLLENBERG TURNS LOOSE shocked those few supporters he i Brief ACCUSED KILLERS ON “COURT FREE BAIL”! has left in the gay community, when ! “WOLLENBERG A DISGRACE TO THE BENCH”, it came out that ne was “making SAYS ONE JUDGE IN CONFIDENCE. deals” or “plea-bargining” with the DISTRICT ATTORNEY FRIETAS’S DEPUTIES four accused killers of Robert Hills borough. Those gays who are in TEXAS LEGISLATURE APPROVE PLEA BARGINS THUGS, PUNKS, AND OTHER SUCH CRIMINALS BACK ONTO THE STREETS the know down at the Hall of Justi OF ANTI-GAY STATEMENT! ce were not at all surprised. Most AUSTIN:A Statement of Intent has OF SAN FRANCISCO! POLICE OFFICERS AND CITIZENS ALIKE DE agreed that this is the “Frietas-way’' passed the Texas State Legislature ..... he has been accused by Supervi which will encourage state college NOUNCE THE MUNICIPAL AND SUPERIOR COURT JUDGES FOR BEING “TOO SOFT” AND sor candidate Rev. Ray Broshears campuses to prohibit any gay stu of being “a coward” in that he re dent organizations. It was introdu TURNING SAN FRANCISCO INTO A ‘JUNGLE ( i Tom Spooner....x>ne of OF CRIME! ’ fuses to face up to the duties at ced by the Rep.