Primates in Peril: the World's 25 Most Endangered Primates 2008–2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea

Primate Conservation 2009 (24): 99–105 Body Measurements for the Monkeys of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea Thomas M. Butynski¹,², Yvonne A. de Jong² and Gail W. Hearn¹ ¹Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA ²Eastern Africa Primate Diversity and Conservation Program, Nanyuki, Kenya Abstract: Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea, has a rich (eight genera, 11 species), unique (seven endemic subspecies), and threat- ened (five species) primate fauna, but the taxonomic status of most forms is not clear. This uncertainty is a serious problem for the setting of priorities for the conservation of Bioko’s (and the region’s) primates. Some of the questions related to the taxonomic status of Bioko’s primates can be resolved through the statistical comparison of data on their body measurements with those of their counterparts on the African mainland. Data for such comparisons are, however, lacking. This note presents the first large set of body measurement data for each of the seven species of monkeys endemic to Bioko; means, ranges, standard deviations and sample sizes for seven body measurements. These 49 data sets derive from 544 fresh adult specimens (235 adult males and 309 adult females) collected by shotgun hunters for sale in the bushmeat market in Malabo. Key Words: Bioko Island, body measurements, conservation, monkeys, morphology, taxonomy Introduction gordonorum), and surprisingly few such data exist even for some of the more widespread species (for example, Allen’s Comparing external body measurements for adult indi- swamp monkey Allenopithecus nigroviridis, northern tala- viduals from different sites has long been used as a tool for poin monkey Miopithecus ogouensis, and grivet Chlorocebus describing populations, subspecies, and species of animals aethiops). -

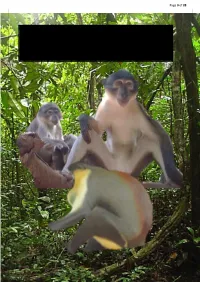

Assessment of Population Density and Structure of Primates in Pandam Wildlife Park, Plateau State, Nigeria

Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726) , 6(2), 2018: 18-35 18 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V6N2-art1503 ASSESSMENT OF POPULATION DENSITY AND STRUCTURE OF PRIMATES IN PANDAM WILDLIFE PARK, PLATEAU STATE, NIGERIA DENSIDAD POBLACIONAL Y ESTRUCTURA DE PRIMATES DIURNOS EN EL PARQUE DE VIDA SILVESTRE EN PANDAM, ESTADO DE PLATEAU, NIGERIA. Gabriel Ortyom Yager*, James Oshita Bukie and Avalumun Emmanuel Kaa, Department of Wildlife and Range Management, University of Agriculture, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. *Correspondent author email & Phone: [email protected]; 08150609846 ABSTRACT A survey of diurnal primate species in Pandam Wildlife Park, Nigeria was conducted to determine its population density and structure. Eight transect lines (2.0km length, 0.02km width) at interval of 1.0km were located as representative samples in the Park within the Three-range stratum (riparian forest, savannah woodland and, swampy area) based on proportional to size of the strata in providing information on the primates’ species present in the Park which include Cercopithecus mona, Erythrocebus patas, Papio anubis and, Chlorocebus tantalus. Direct method of animal sighting was employed. Data was collected and analyzed using descriptive statistics, ANOVA and diversity indices. The results showed that savannah woodland strata had more number of individual species encountered (132) and the lowest was the swampy area. Also the savannah woodland had the highest species diversity and richness while the riparian forest strata had the highest number of species evenness. More so, Cercopithecus tantalus was widespread throughout the Park among other primates and Cercopithecus mona is most likely to decline even more rapidly than others since they inhabit the very tall trees. -

2016 Activities Report Wapca in Action Creating Viable Long-Term Solutions

Page 0 of 28 WEST WEST AFRICAN AFRICAN PRIMATE PRIMATE CONSERVATION CONSERVATION ACTION ACTION 2015 Annual Report Annual Report 2016 Annual Report West African Primate Conservation Action Annual Report 2016 Page 1 of 28 WEST AFRICAN PRIMATE CONSERVATION ACTION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Andrea Dempsey. BA. MSc. Country Coordinator West African Primate Conservation Action P.O. Box GP1319 Accra, Ghana Email: [email protected] Website: www.wapca.org West African Primate Conservation Action Annual Report 2016 Page 2 of 28 Update from the WAPCA-Ghana Country Coordinator WAPCA members, sponsors, partners and friends have continued to generously support us over the past year allowing us to continue the work here in Ghana at both the Critically Endangered Primate Breeding Centre, Kumasi Zoo and also in the field working with communities to protect the forests and the wild primates that inhabit them, for which we are hugely grateful. We’d like to particularly welcome our newest WAPCA member Africa Alive. WAPCA Ghana Board also grew with five new Board members joining – Dr Selorm Tettey, Edward Wiafe, Kwame Tutu, Micheal Abedi-Lartey and Noah Gbexede. The Board also elected David Tettey as our new Chairman. David has been Acting Chairman since the sad passing of our late Chairman – we look forward to him guiding us over the coming years. 2016 saw many visitors – David Morgan from Colchester Zoo, Heather MacIntosh, Hannah Joy and Miranda Crosby from ZSL London Zoo, Tobias Kremer from Heidelberg Zoo, Sabrina Linn from Frankfurt Zoo and Nicky Plaskitt from Paradise Park – I wish to thank them for spending time with our team here and sharing their expertise and knowledge, as well as the useful gifts which they donated including enrichment items donated from Zoo Wizards. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 09:14:05PM Via Free Access 218 Rode-Margono & Nekaris – Impact of Climate and Moonlight on Javan Slow Lorises

Contributions to Zoology, 83 (4) 217-225 (2014) Impact of climate and moonlight on a venomous mammal, the Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus Geoffroy, 1812) Eva Johanna Rode-Margono1, K. Anne-Isola Nekaris1, 2 1 Oxford Brookes University, Gipsy Lane, Headington, Oxford OX3 0BP, UK 2 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: activity, environmental factors, humidity, lunarphobia, moon, predation, temperature Abstract Introduction Predation pressure, food availability, and activity may be af- To secure maintenance, survival and reproduction, fected by level of moonlight and climatic conditions. While many animals adapt their behaviour to various factors, such nocturnal mammals reduce activity at high lunar illumination to avoid predators (lunarphobia), most visually-oriented nocturnal as climate, availability of resources, competition, preda- primates and birds increase activity in bright nights (lunarphilia) tion, luminosity, habitat fragmentation, and anthropo- to improve foraging efficiency. Similarly, weather conditions may genic disturbance (Kappeler and Erkert, 2003; Beier influence activity level and foraging ability. We examined the 2006; Donati and Borgognini-Tarli, 2006). According response of Javan slow lorises (Nycticebus javanicus Geoffroy, to optimal foraging theory, animal behaviour can be seen 1812) to moonlight and temperature. We radio-tracked 12 animals as a trade-off between the risk of being preyed upon in West Java, Indonesia, over 1.5 years, resulting in over 600 hours direct observations. We collected behavioural and environmen- and the fitness gained from foraging (Charnov, 1976). tal data including lunar illumination, number of human observ- Perceived predation risk assessed through indirect cues ers, and climatic factors, and 185 camera trap nights on potential that correlate with the probability of encountering a predators. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

In Situ Conservation

NEWSN°17/DECEMBER 2020 Editorial IN SITU CONSERVATION One effect from 2020 is for sure: Uncertainty. Forward planning is largely News from the Little Fireface First, our annual SLOW event was impossible. We are acting and reacting Project, Java, Indonesia celebrated world-wide, including along the current situation caused by the By Prof K.A.I. Nekaris, MA, PhD by project partners Kukang Rescue Covid-19 pandemic. All zoos are struggling Director of the Little Fireface Project Program Sumatra, EAST Vietnam, Love economically after (and still ongoing) Wildlife Thailand, NE India Primate temporary closures and restricted business. The Little Fireface Project team has Investments in development are postponed Centre India, and the Bangladesh Slow at least. Each budget must be reviewed. been busy! Despite COVID we have Loris Project, to name a few. The end In the last newsletter we mentioned not been able to keep up with our wild of the week resulted in a loris virtual to forget about the support of the in situ radio collared slow lorises, including conference, featuring speakers from conservation efforts. Some of these under welcoming many new babies into the the helm of the Prosimian TAG are crucial 11 loris range countries. Over 200 for the survival of species – and for a more family. The ‘cover photo’ you see here people registered, and via Facebook sustainable life for the people involved in is Smol – the daughter of Lupak – and Live, more than 6000 people watched rd some of the poorest countries in the world. is our first 3 generation birth! Having the event. -

Primate Connections

Primate Connections !"#! Foreword by Dr. Simon Bearder Cover Photo by Noel Rowe THANK YOU! ear Friends, To complete the conservation circle, this DThank you for your support! By purchasing this calendar, you calendar also builds capacity in the places have become part of the Primate Connection – a network of grass where primates need it most. Part of the roots primate conservation organizations working collectively to proceeds from the sale of this calendar are raise awareness about the plight of primates, while generating sent to Oxford Brookes University’s Pri innovative programs that are helping to protect primates throughout mate HabitatCountry Student Scholarship. the world. © Sam Trull This scholarship grants students who come ! "#$%!&'&()*'+,!-'.!/00!10#,.*02!%0*0!3#/!#/402!,'!/%#*0!35,%! from countries where primates live a chance us a synopsis of the conservation issues they face and the creative to receive a Master’s degree in Primate Conservation Biology. ways they go about tackling them. Their renditions, along with A heartfelt thank you is given to those individuals from each photos of some of the rarest and most beautiful primates on the organization that made this project possible: Andrea Donaldson, planet, were then compiled to make this calendar. Helen Thirlway, Shirley McGreal, Steve Coan, Marc Myers, Noel As you read through the pages, you’ll become familiar with Rowe, Lis Key, Aura BeckhoferFialho, Sam Trull, Liz Tyson, Sam some of the most dedicated primate conservation organizations in Shanee, Joy Lliff, Aoife Healy, Pedro MendezCarvajal, Dominique the world. The spectrum of mitigation strategies they employ is both Aubin, Steve Blumkin, Brook Aldrich, Petra Osterberg, Sarah Rus inspiring and vital. -

Endangered Species

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Endangered species From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents For other uses, see Endangered species (disambiguation). Featured content "Endangered" redirects here. For other uses, see Endangered (disambiguation). Current events An endangered species is a species which has been categorized as likely to become Random article Conservation status extinct . Endangered (EN), as categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Donate to Wikipedia by IUCN Red List category Wikipedia store Nature (IUCN) Red List, is the second most severe conservation status for wild populations in the IUCN's schema after Critically Endangered (CR). Interaction In 2012, the IUCN Red List featured 3079 animal and 2655 plant species as endangered (EN) Help worldwide.[1] The figures for 1998 were, respectively, 1102 and 1197. About Wikipedia Community portal Many nations have laws that protect conservation-reliant species: for example, forbidding Recent changes hunting , restricting land development or creating preserves. Population numbers, trends and Contact page species' conservation status can be found in the lists of organisms by population. Tools Extinct Contents [hide] What links here Extinct (EX) (list) 1 Conservation status Related changes Extinct in the Wild (EW) (list) 2 IUCN Red List Upload file [7] Threatened Special pages 2.1 Criteria for 'Endangered (EN)' Critically Endangered (CR) (list) Permanent link 3 Endangered species in the United -

Online Appendix for “The Impact of the “World's 25 Most Endangered

Online appendix for “The impact of the “World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates” list on scientific publications and media” Table A1. List of species included in the Top25 most endangered primate list from the list of 2000-2002 to 2010-2012 and used in the scientific publication analysis. There is the year of their first mention in the Top25 list and the consecutive mentions in the following Top25 lists. Species names are the current species names (based on IUCN) and not the name used at the time of the Top25 list release. First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Species mention mention mention mention mention mention Ateles fusciceps 2006 Ateles hybridus 2006 2008 2010 Ateles hybridus brunneus 2004 Brachyteles hypoxanthus 2000 2002 2004 Callicebus barbarabrownae 2010 Cebus flavius 2010 Cebus xanthosternos 2000 2002 2004 Cercocebus atys lunulatus 2000 2002 2004 Cercocebus galeritus galeritus 2002 Cercocebus sanjei 2000 2002 2004 Cercopithecus roloway 2002 2006 2008 2010 Cercopithecus sclateri 2000 Eulemur cinereiceps 2004 2006 2008 Eulemur flavifrons 2008 2010 Galagoides rondoensis 2006 2008 2010 Gorilla beringei graueri 2010 Gorilla beringei beringei 2000 2002 2004 Gorilla gorilla diehli 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Hapalemur aureus 2000 Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis 2000 Hoolock hoolock 2006 2008 Hylobates moloch 2000 Lagothrix flavicauda 2000 2006 2008 2010 Leontopithecus caissara 2000 2002 2004 Leontopithecus chrysopygus 2000 Leontopithecus rosalia 2000 Lepilemur sahamalazensis 2006 Lepilemur septentrionalis 2008 2010 Loris tardigradus nycticeboides -

REVIEW ARTICLE Agroecosystems and Primate Conservation in the Tropics: a Review

American Journal of Primatology 74:696–711 (2012) REVIEW ARTICLE Agroecosystems and Primate Conservation in The Tropics: A Review ∗ ALEJANDRO ESTRADA1 , BECKY E. RABOY2,3, AND LEONARDO C. OLIVEIRA3-6 1Estaci´on de Biolog´ıa Tropical Los Tuxtlas Instituto de Biolog´ıa, Universidad Nacional Aut´onoma de M´exico, Mexico City, Mexico 2Conservation Ecology Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC 3Instituto de Estudos S´ocioambientais do Sul da Bahia (IESB), Ilh´eus-BA, Brazil 4Programa de P´os-Gradua¸c˜ao em Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 5Programa de P´os-Gradua¸c˜ao em Ecologia e Conserva¸c˜ao da Biodiversidade, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Ilh´eus-BA, Brazil 6Bicho do Mato Instituto de Pesquisa, Belo Horizonte-MG, Brazil Agroecosystems cover more than one quarter of the global land area (ca. 50 million km2) as highly simplified (e.g. pasturelands) or more complex systems (e.g. polycultures and agroforestry systems) with the capacity to support higher biodiversity. Increasingly more information has been published about primates in agroecosystems but a general synthesis of the diversity of agroecosystems that primates use or which primate taxa are able to persist in these anthropogenic components of the landscapes is still lacking. Because of the continued extensive transformation of primate habitat into human-modified landscapes, it is important to explore the extent to which agroecosystems are used by primates. In this article, we reviewed published information on the use of agroecosystems by primates in habitat countries and also discuss the potential costs and benefits to human and nonhuman primates of primate use of agroecosystems. -

Population Composition and Density of Mona Monkey in Lekki Concervation Centre, Lekki, Lagos, Nigeria

Olaleru et al., 2020 Journal of Research in Forestry, Wildlife & Environment Vol. 12(3) September, 2020 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] http://www.ajol.info/index.php/jrfwe This work is licensed under a jfewr ©2020 - jfewr Publications 259 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License ISBN: 2141 – 1778 Olaleru et al., 2020 POPULATION COMPOSITION AND DENSITY OF MONA MONKEY IN LEKKI CONCERVATION CENTRE, LEKKI, LAGOS, NIGERIA *1, 2Olaleru, F., 1Omotosho, O. O. and 1, 2Omoregie, Q. O. 1Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria. 2Centre for Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Management, University of Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria. * Corresponding Author: [email protected]; + 234 807 780 0748 ABSTRACT The mona monkey (Cercopitecus mona) is the only non-human primate in Lekki Conservation Centre (LCC), a 78 hectares Strict Nature Reserve located in a peri-urban part of Lagos, Nigeria. This study aimed to of population composition and density of mona monkeys in LCC. Total count method using woods walk ways and perimeter road as line transects was used for the enumeration. The censuses were conducted for 27 days in October, November, and December, 2018. Counts were carried out between 06:30 and 10:30 hours for 22 days, and between 16:30 and 19:00 hours for five days. Monkeys were enumerated by counting all sighted individuals on both sides of the walk ways, and other study points. Data was subjected to analysis of variance to compare the monthly means, and statistically significant means (P < 0.05) were separated using Tukey post hoc test. -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA.