The Civil War in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 8, No. 1, January, 1946

INTERNAL B UL L E T.I N SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY 116 University Place, New York 3, N. Y. Volume VIII Number I January 1948 ~ .. Price ZO Cenu CONT~S The First National Conference of the RCP and Its Empirical Leadership, by Pierre Frank . I LeHer from the Revolutionary Communist Party .... 7 Reply to Letter from the Revolutionary Communist Party, by M. Stein .. 9 Copy of a Letter from Gerry Healy to a Friend 11 Letters to England, by Felix Morrow .. 11 Comrade Stuart and the ILP-Fads Versus Baseless Assertions, by Bill Hunter 12 The Minority's AHitude toward Theory, by S. Simmons.............. 16 The First National Conference of the Rep and Its Empirical Leadership By PIERRE FRANK It is only several weeks since the racHcaUzation of the labor numerical strength and without political character. 'n1e most ing masses in Great Britain, together with that of the laboring . important progress was 1ihe un1floation. To be sure, it could !lIM masses in the whole world and most particularly on the European resolve aLl the problems raised by the transition trom a cirCle continent, expressed itself in the vote which gave the Labour existence dominated by clique struggles to the life of a revolu Party an overwhelming parUamentary majOrity. tionary grouping seeking to open a path for itself into the work All the members of the Fourth International have taken note ing class. Bllt at least it did eliminate a number of obstacles of the importance of this vote in the present period. 'nle con ha.nging over from the past. -

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

Fourth International

.. .... ..... ...... ......... .... , . October 1940 Fourth n~ernational I~he Monthly Magazine of the Socialist Workers Party Twenty Cents letter from H, T. of Los Angeles. IIM anager’s Column FOURTH INTERNATIONAL SinCeany comment would be su- II1[ PuZd48hedbv the NationaZUotnm{tteeof the 8o04@et Wovker8Partu perfluous, we merely print the ! letter as received. “Dear Mike: Volume I October 1940 No. 5 (Whole No. 5) The magazine is late in reach- Where is the September issue of Published monthly by the SOCIALIST WORKZRS PARTW, 116 Uni- ing the worker%first because of versity Place, New York, N. Y. Telephone: ALgonquin 4-8547. the FOURTH INTERNATION- Subscription rates: $2.00 per year; bundles, 14c for 5 copies and AL? The irregular appearance financial difficulties, and then up. Canada and Foreign: $2.50 per year; bundles 16c for 5 because the contents had to be copies and up. Entered as seeond-ckiaematter May 20, 1940, at the of the F.I. has to stop. If the post Officeat New York N.Y., under the Act of Maroh 8,.1879. changed to make it a memorial F.I. is to increase its influence issue. That our tribute to Trot- Editoi+al Board: and its readers, it must appear JAMES P. CANNON JOSEPH HANSEN regularly each month, and on sky should have been delayed ALBERT GOLDMAN FELIX MORROW of the month. A drive because of a shortage of moneY BU8h&%T lf~ag~: the first is a bitter situation. Yet, who MICHAEL CORT must be started, similar to the better than the Old Man knew Trotsky Defense Fund Drive to of the heartaches involved in TA B L E O F CONT EN TS raise adequate financial support keeping a revolutionary press for the continued existence of With Trotsky to the End . -

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago Pamphlets Explanatory Power I 6 fDK246.S2 M. Dobrov Chto takoe burzhuaziia? [What is the Bourgeoisie?] Petrograd: Petrogr. Torg. Prom. Soiuz, tip. “Kopeika,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 39 fDK246.S2 S.K. Neslukhovskii Chto takoe sotsializm? [What is Socialism?] Petrograd: K-vo “Svobodnyi put’”, [n.d.] Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 10 fDK246.S2 Aleksandra Kollontai Kto takie sotsial-demokraty i chego oni khotiat’? [Who Are the Social Democrats and What Do They Want?] Petrograd: Izdatel’stvo i sklad “Kniga,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets I 7 fDK246.S2 Vatin (V. A. Bystrianskii) Chto takoe kommuna? (What is a Commune?) Petrograd: Petrogradskogo Soveta Rabochikh i Krasnoarmeiskikh Deputatov, 1918 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 32 fDK246.S2 L. Kin Chto takoe respublika? [What is a Republic?] Petrograd: Revoliutsionnaia biblioteka, 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 31 fDK246.S2 G.K. Kryzhitskii Chto takoe federativnaia respublika? (Rossiiskaia federatsiia) [What is a Federal Republic? (The Russian Federation)] Petrograd: Znamenskaia skoropechatnaia, 1917 1 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E42 fDK246.S2 O.A. Vol’kenshtein (Ol’govich): Federalizm v Rossii [Federalism in Russia] Knigoizdatel’stvo “Luch”, [n.d.] fDK246.S2 E33 I.N. Ignatov Gosudarstvennyi stroi Severo-Amerikanskikh Soedinenykh shtatov: Respublika [The Form of Government of the United States of America: Republic] Moscow: t-vo I. D. Sytina, 1917 fDK246.S2 E34 K. Parchevskii Polozhenie prezidenta v demokraticheskoi respublike [The Position of the President in a Democratic Republic] Petrograd: Rassvet, 1917 fDK246.S2 H35 Prof. V.V. -

Roosevelt Demands Slave Labor Bill in First Congress Message

The 18 And Their Jailers SEE PAGE 3 — the PUBLISHEDMILITANT IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE VOL. IX—No. 2 NEW YORK, N. Y„ SATURDAY, JANUARY 13, 1943' 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS Labor Leaders Roosevelt Demands Slave Labor Will Speak A t Bill In First Congress Message Meeting For 12 © ' Congress Hoists Its Flag The C ivil Rights Defense Corhmittee this week announced First Act of New a list of distinguished labor and civil liberties leaders who will Calls For Immediate Action participate in the New York ‘‘Welcome Home” Mass Meeting for James P. Cannon, Albert Goldman, Farrell Dobbs and Felix Congress Revives Morrow, 4 of the 12 imprisoned Trotskyists who. are being re On Forced Labor Measures leased from federal prison on January 24. The meeting will be Dies Committee held at the Hotel Diplomat, 108 W. 43rd Street, on February Political Agents of Big Business Combine 2, 8 P. M. ®---------------------------------------------- By R. B e ll To Enslave Workers and Paralyze Unions Included among the speakers CRDC Fund Drive The members of the new Con who will greet the Minneapolis gress had hardly warmed their Labor Case prisoners are Osmond Goes Over Top By C. Thomas K. Fraenkel, Counsel for the seats when a coalition of Roose NEW YORK CITY, Jan. 8— American Civil Liberties Union; velt Democrats and Dewey Re-' Following on the heels of a national campaign A total of $5,500 was con James T. Farrell, noted novelist publicans led by poll-tax Ran tributed in the $5,000 Christ to whip up sentiment for labor conscription, Roose and CRDC National Chairman; kin of Mississippi, anti-semite, mas Fund Campaign to aid Benjamin S. -

The Spanish Communist Party in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), Vol

The Defence of Madrid: The Spanish Communist Party in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), Vol. Amanda Marie Spencer Ph. D. History Department of History, University of Sheffield June 2006 i Contents: - List of plates iii List of maps iv Summary v Introduction 5 1 The PCE during the Second Spanish Republic 17 2 In defence of the Republic 70 3 The defence of Madrid: The emergence of communist hegemony? 127 4 Hegemony vs. pluralism: The PCE as state-builder 179 5 Hegemony challenged 229 6 Hegemony unravelled. The demise of the PCE 274 Conclusion 311 Appendix 319 Bibliography 322 11 Plates Between pp. 178 and 179 I PCE poster on military instruction in the rearguard (anon) 2a PCE poster 'Unanimous obedience is triumph' (Pedraza Blanco) b PCE poster'Mando Unico' (Pedraza Blanco) 3 UGT poster'To defend Madrid is to defend Cataluna' (Marti Bas) 4 Political Commissariat poster'For the independence of Spain' (Renau) 5 Madrid Defence Council poster'First we must win the war' (anon) 6a Political Commissariat poster Training Academy' (Canete) b Political Commissariat poster'Care of Arms' (anon) 7 lzquierda Republicana poster 'Mando Unico' (Beltran) 8 Madrid Defence Council poster'Popular Army' (Melendreras) 9 JSU enlistment poster (anon) 10 UGT/PSUC poster'What have you done for victory?' (anon) 11 Russian civil war poster'Have you enlisted as a volunteer?' (D.Moor) 12 Poster'Sailors of Kronstadt' (Renau) 13 Poster 'Political Commissar' (Renau) 14a PCE Popular Front poster (Cantos) b PCE Popular Front poster (Bardasano) iii Maps 1 Central Madrid in 1931 2 Districts of Madrid in 1931 2 3 Province of Madrid 3 4 District of Cuatro Caminos 4 iv Summary The role played by the Spanish Communist Party (Partido Comunista de Espana, PCE) during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 remains controversial to this day. -

Revolution and Counterrevolution in Catalonia – Carlos Semprún Maura

Revolution and Counterrevolution in Catalonia – Carlos Semprún Maura Introduction to the Spanish Edition I wrote this book between 1969 and 1971, when the tremors of the May-June 1968 outbreak in France had not yet subsided, and when a wide range of topics, new for many people, nourished actions, discussions, projects, journals and books. Among these topics, of course, were the libertarian revolutions and the shopworn theme of self-management. To me it seemed that the logical as well as the obvious thing to do was to participate in my own way in these discussions and in the critique of totalitarianism (“red” fascism as well as the “white” variety), by writing a book about the experiences of “self- management” in Catalonia and Aragon in 1936-1939, concerning which almost no one (if not absolutely no one) knew anything in France at that time. I was myself only then discovering the importance of these phenomena as I engaged in research and gathered documents and data for the book. During those same years, it had become fashionable for Parisian publishers to carry some “leftist” titles in their catalogues, in order to satisfy a new youthful customer base and to thus increase the profits of the various publishing houses. This book, however, was offered to a whole series of publishers without being accepted by any of them, until it was to “miraculously” find a home with a respectable, and originally Catholic, publisher (Mame), that was at the time attempting to change its image to keep pace with the times. My book did not bring it any good luck since its publisher went out of business shortly thereafter, sinking into the most total bankruptcy…. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Ken Magazine, the Consumer Market, and the Spanish Civil

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of English POLITICS, THE PRESS, AND PERSUASIVE AESTHETICS: SHAPING THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN AMERICAN PERIODICALS A Dissertation in English by Gregory S. Baptista © 2009 Gregory S. Baptista Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 ii The dissertation of Gregory S. Baptista was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark S. Morrisson Associate Professor of English Graduate Director Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Robin Schulze Professor of English Department Head Sandra Spanier Professor of English and Women’s Studies James L.W. West III Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English Philip Jenkins Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of the Humanities *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the presentation of the Spanish Civil War in selected American periodicals. Understanding how war-related works functioned (aesthetically and rhetorically) requires a nuanced view of the circumstances of their production and an awareness of their immediate cultural context. I consider means of creation and publication to examine the complex ways in which the goals of truth-seeking and truth-shaping interacted—and were acted upon by the institutional dynamics of periodical production. By focusing on three specific periodicals that occupied different points along a line leading outward from the mainstream of American culture, I examine the ways in which certain pro- Loyalist writers and editors attempted to shape the truth of the Spanish war for American readers within the contexts and inherent restrictions of periodical publication. I argue that responses to the war in these publications are products of a range of cultural and institutional forces that go beyond the political affiliations or ideological stances of particular writers. -

Spain in the Struggle Against Fascism for Almost Three Months the Spanish People Have Been Carrying on a Heroic Struggle Against the Fascist Insurgents

Communist International Nov. (11), 1936, pp. 1418-1438 Spain in the Struggle Against Fascism For almost three months the Spanish people have been carrying on a heroic struggle against the fascist insurgents. Workers from Madrid and Catalonia, peasants from Andalusia and Estremadura, office employees, professors, poets and musicians, are fighting shoulder to shoulder at the front. The whole nation is conducting a life-and-death struggle against a handful of generals, enemies of peace and liberty, who, with the aid of the cutthroat soldiers of the Foreign Legion and duped Moroccan troops, want to restore the rule of the landlords and the church, and to sell the country piecemeal to the German and Italian fascists. This is a struggle of the millions for bread and liberty, for land and work, for the independence of their country. It is a struggle of democracy against the dark forces of reaction and fascism. It is a struggle of the republic against those who are violating the orderly life and peaceful labor of the workers and peasants. It is a struggle against the instigators of war; it is a struggle for peace. The relationship of class forces in Spain is such that fascism has the vast majority of the Spanish people against it, that the people, united in the alliance of the working class, peasants, and working people of the towns, would long since have settled with the revolt, were it not that behind the backs of the Spanish fascists stand the forces of world reaction, and first and foremost, German and Italian fascism. -

Spanish Civil War of 1936 VMUN 2017 Background Guide 1

Spanish Civil War of 1936 VMUN 2017 Background Guide 1 VANCOUVER MODEL UNITED NATIONS the sixteenth annual conference | January 20-22, 2017 Dear Delegates, Alvin Tsuei Welcome to the Republican Cabinet of Spain – 1936. Together we will embark Secretary-General on a journey through the matinée of World War II. This committee – to an even greater extent than other committees – is a role play committee, with the difference being that you are playing a historical figure in a historical period rather than representing a country. We will outline your positions, who held Chris Pang them, and their ideology and allegiance in the Personal Portfolios (to be Chief of Staff discussed later); however, as there is limited information on these people, and what happens in our committee will be different from real life, you will all have Eva Zhang some leeway with them. Director-General This committee will run as a continuous moderated caucus, with chances for Arjun Mehta motions and points always available. This means you will not need to motion for Director of Logistics moderated caucuses, unless you wish to force discussion on a specific topic for a fixed period of time. Also, as you are not necessarily all agreeing on things, but rather having periods of discussion followed by action in a certain division, this committee will be mainly based around directives. Some directives may need more signatories, or may need to be implemented as a resolution instead of a Graeme Brawn directive. That will be up to the director's discretion. USG General Assemblies An important note is this committee's policy on delegate's being removed from Ryan Karimi the committee. -

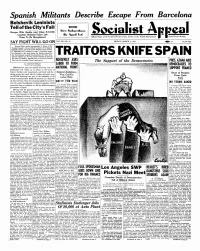

Spanish Militants Describe Escape from Barcelona Bolshevik Leninists Tell of the City's Fall 1000 New Subscribers Escape with Gorkin and Other P.O.U.M

Spanish Militants Describe Escape From Barcelona Bolshevik Leninists Tell of the City's Fall 1000 New Subscribers Escape With Gorkin and Other P.O.U.M. Socialist Appeal Leaders; Stalinist Police Left By April 1st! Them To Be Slaughtered Official Organ of the Socialist Workers Party, Section of the Fourth International Issued Twice Weekly SAY FIGHT WILL GO ON VOL. Ill—No. 12 FRIDAY, MARCH 3, 1939 375 3? per copy Terence Phelan, special correspondent in France of the "Socialist Appeal," met and talked to leaders of the Spanish Bolshevik-Leninists and the P.O.U.M. (Workers' Party of Marx ist Unification) who managed to make a miraculous escape from Barcelona a few hours before the Fascists entered the city. Having barely escaped the executioners of Franco, these TRAITORS KNIFE SPAIN Spanish militants now face the constant menace of arrest by the police of Daladier, erstwhile hero of the French People's Front who has recognized Franco's government. ROOSEVELT ASKS The Support of the Democracies PRES. AZANA AIDS By TKKKNCE PHELAN LABOR TO FORM / Special to the Socialist Appeal) DEMOCRACIES TO PERPIGNAN (near the Spanish Frontier), Feb. 16— NATIONAL FRONT Deliberately left locked up in prison, at the mercy of SUPPORT FRANCO Franco’s bombers and executioners, and saved only by a Political Ambitions, Head of People's daring escape that reads like the wildest adventure story, War, Call For Front Quits the POUM leadership and part of the leadership of the Labor Unity Fourth Internationalist Bolshevik-Leninists are temporar Paris ily safe in France. They are scattering rapidly for cover be UNITY FOR WAR fore the police bloodhounds of French capitalism, which NO TERMS ASKED In an identical letter to W illiam persecutes them as ruthlessly as did the Stalino-bourgeois Green, president of the American Arriving at the logical conclu government of Spain.