Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to the Democratic National Committee, the DNC Rules Committee, and All Delegates to the Democratic National Convention

Letter to the Democratic National Committee, the DNC Rules Committee, and all delegates to the Democratic National Convention: The undersigned organizations hope that all Democrats agree that the will of the voters should be decisive in determining the Democratic nominees for the country’s highest offices. We therefore urge the Democratic Party – via action at this month’s Democratic National Convention – to eliminate the concept of so-called “superdelegates.” This change would not impact the ongoing nomination proceedings, but would take effect for all future national nominee selection processes and conventions. The superdelegate system is unrepresentative, contradicts the purported values of the party and its members, and reduces the party’s moral authority. • The system undermines representative democracy and means that the electorate is not necessarily decisive in determining who will be the Democratic nominees for president and vice president and dilutes the voters’ say over the party’s platform and the rules under which it operates. Astonishingly, these unelected delegates have essentially as much weight as do the pledged delegates from the District of Columbia, 4 territories, and 24 states combined. • The system undermines the Democratic Party's commitment to gender equity. While the party’s charter rightfully mandates that equal numbers of pledged delegates be male and female, a near super-majority of superdelegates are men. • The Democratic Party prides itself on its commitment to racial justice and the racial diversity of its ranks. Yet the superdegelates appears to skew the party away from appropriate representation of communities of color: Proportionately, approximately 20% fewer of this year’s superdelegates hail from communities of color than was true of the 2008 and 2012 pledged delegate cohorts, or of the voters who supported President Obama in those years’ general elections. -

The Charter the Bylaws

THE CHARTER & THE BYLAWS OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF THE UNITED STATES As Amended by The Democratic National Committee August 25, 2018 CONTENTS CHARTER OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF THE UNITED STATES 1 PREAMBLE 1 ARTICLE ONE ........................................ The Democratic Party of the United States of America 2 ARTICLE TWO ....................................... National Convention 3 ARTICLE THREE ................................... Democratic National Committee 5 ARTICLE FOUR ..................................... Executive Committee 5 ARTICLE FIVE ....................................... National Chairperson 6 ARTICLE SIX.......................................... Party Conference 6 ARTICLE SEVEN ................................... National Finance Organizations 6 ARTICLE EIGHT..................................... Full Participation 7 ARTICLE NINE ....................................... General Provisions 9 ARTICLE TEN ........................................ Amendments, Bylaws, and Rules 9 RESOLUTION OF ADOPTION BYLAWS Adopted Pursuant to the Charter of the Democratic Party of the United States 11 ARTICLE ONE ........................................ Democratic National Convention 11 ARTICLE TWO ....................................... Democratic National Committee 20 ARTICLE THREE ................................... Executive Committee 22 ARTICLE FOUR ..................................... National Finance Organizations 22 ARTICLE FIVE ....................................... Amendments i CHARTER CHARTER OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF THE -

Nancy Green Speech February 3 2009

Nancy Greens Campaign Speech for the election of Chapter Chair of the Berlin Chapter of Democrats Abroad Germany on February 3, 2009 Barack Obama has been elected president …Wow… How did this happen? It was no accident!! Of course there are many factors that lead to the outcome of this historic election … which will be analyzed at the local Stammtisch and by scholars and institutions far into the future. One thing I can say from my perspective here in Berlin is. We had something to do with it. And people like us had something to do with it. From Berlin and Munich, Heidelberg, and Landstuhl, to Rome, Vancouver, London, Madrid, Ukraine, Lebanon and Israel, to Denver…. Democrats all over the world had something to do with the outcome of this election. We also had some help …. George Bush…. Sarah Palin, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld John McCain… I could go on and on, but I only have 10 minutes… The missteps of the Republican Party are one major factor. Other factors include the Organization of the Democratic Party the Obama Campaign, The leadership of Howard Dean and people like us at the grass-roots. Then there is Barack Obama himself, who has inspired millions. Change has come about because we have had leadership. We are here because we care about our country and, adhering to the basic principles of the Democratic Party, we want to bring about changes in our nation’s policies regarding, to name only some the economy, health care, education, the environment, equal rights, scientific research, support for the arts, foreign policy, Iraq, Quantanemo and Habeus Corpus. -

Carter/Mondale 1980 Re-Election Committee Papers: a Guide to Its Records at the Jimmy Carter Library

441 Freedom Parkway NE Atlanta, GA 30307 http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov Carter/Mondale 1980 Re-Election Committee Papers: A Guide to Its Records at the Jimmy Carter Library Collection Summary Creator: Carter/Mondale 1980 Re-Election Committee. Title: Carter/Mondale 1980 Re-Election Committee Papers Dates: 1977-1980 Quantity: 171 linear feet, 1 linear inch open for research, 391 containers Identification: Accession Number: 80-1 National Archives Identifier: 593160 Scope and Content: This collection contains letters, correspondence, memoranda, handwritten notes, studies, speeches, recommendations, position papers, press releases, briefing books, notebooks, proposals, studies, voter lists, reports, political statements, publications and news clippings. These records document various aspects of President Carter’s 1980 re-election campaign. This includes the formation of political strategy; polling data; legal and procedural issues; administrative items such as finance, fundraising and budget matters; statements on issues; scheduling; speeches; field staff operations in states and regions; polling data; voter lists; public correspondence and materials relating to press issues. Creator Information: Carter/Mondale 1980 Re-Election Committee Restrictions: Restrictions on Access: These papers contain documents restricted in accordance with Executive Order 12958, which governs National Security policies, and material which has been closed in accordance with the donor’s deed of gift. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction: Copyright interest in -

The Visible Primaries

THE VISI PRIMARIES BLE The Rhodes Cook Letter December 2003 The Rhodes Cook Letter DECEMBER 2003 / VOL. 4, NO. 6 Contents Enter the Voters . 3 Chart: Democratic Success Index. 3 Chart: Republicans Nominate Early Front-Runners, Democrats often Don’t . 4 Map & Chart: 2004 Nominating Season at a Glance . 6 Chart: 2004 Democratic Delegate Selection by Month . 8 Chart: 2000 Democratic and Republican Primary Results. 10 Chart: Iowa, New Hampshire and the Road to Nomination . 12 Map & Chart : A Thumbnail Look at the ‘Kingmakers’ . 13 Chart : Gephardt’s 1988 Presidential Run . 14 Chart : At the End of the Third Quarter: Money and the Polls . 15 Chart: The Ups and Downs of the ‘Invisible Primary’ . 16 Map & Chart: Bush and the Electoral College Map . 18 Looking Back, Looking Ahead . 19 What’s up in 2004 . 19 2003 Gubernatorial Elections: The Constant is Change . 20 Changing Composition of the 108th Congress . 21 Subscription Page . 22 The Rhodes Cook Letter is published by Rhodes Cook. Web: is $99. Make check payable to “The Rhodes Cook Letter” and rhodescook.com. E-mail: [email protected]. Design by send it, along with your e-mail address, to P.O. Box 574, Landslide Design, Rockville, MD. “The Rhodes Cook Letter” is Annandale, VA. 22003. See the last page of this newsletter for published on a bimonthly basis. A subscription for six issues a subscription form. All contents are copyrighted ©2004 Rhodes Cook. Use of the material is welcome with attribution, although the author retains full copyright over the material contained herein. The Rhodes Cook Letter • December 2003 2 Enter the Voters he Democratic presidential nominating campaign is about to move from the political equiva- Tlent of tryouts in New Haven to the make-or-break of Broadway. -

Red and Blue America Redux

R AMERICAED AND BLUE REDUX The Rhodes Cook Letter October 2003 The Rhodes Cook Letter OCTOBER 2003 / VOL. 4, NO. 5 Contents Bush, The Democrats and ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ America . 3 Chart: Red & Blue America Summary . 4 Chart: Red & Blue USA ‘02 Results, ‘04 Action . 5 Map & Chart: Bush and the Map, 2000-04 . 8 Chart: The President’s Party at Midterm and Presidential Elections that Follow . 9 Chart & Graph: GOP Gains Separation in ‘02 House Vote . 10 California: The Cornerstone of ‘Blue’ America . 11 Chart : Turnout Comparison: The Recall vs. High Profile Races of ‘02 . 11 Map & Chart: The Recall Vote by County. 12 Chart: Ronnie & Arnold: Boffo Political Debuts . 13 Tentative 2004 Democratic Primary Calendar and Delegate Count . 15 Other 2003 Elections: Gubernatorial, House Candidates at Ballot Box . 16 Changing Composition of the 108th Congress... And Governorships . 17 Subscription Page. 18 Looking Ahead: The next issue in December will focus on the fast-approaching presi- dential nominating season, the state of the Democratic campaign, and the varied terrain of primaries and caucuses the party’s candidates will face. The Rhodes Cook Letter is published by Rhodes Cook. Web: tion for six issues is $99. Make check payable to “The Rhodes rhodescook.com. E-mail: [email protected]. Design by Cook Letter” and send it, along with your e-mail address, to Landslide Design, Rockville, MD. “The Rhodes Cook Letter” is P.O. Box 574, Annandale, VA. 22003. See the last page of this being published on a bimonthly basis in 2003. A subscrip- newsletter for a subscription form. -

The Invisible Primary and the 1996 Presidential Nomination

The Invisible Primary and the 1996 Presidential Nomination Thomas R. Marshall, University of Texas at Arlington The 1996 presidential nominations process will not begin with the first state primaries and caucuses. By January 1996 the candidates had already spent millions of dollars and thousands of days campaigning during the "in visible primary." The 1996 nominations race features several new prac tices—such as the front-loading of delegate-selection events, and the re- emergence of Washington insiders as the early GOP leaders. For the first time since 1964 the Democrat Party did not face a spirited nominations race. This article reviews the prenomination season for the 1996 presidential race with evidence available by early January 1996. Public Opinion Public opinion remained relatively stable during the 1995 "invisible primary," just as it typically has in recent presidential contests.1 Heavy spending in key primary and caucus states, debates among the candidates, and the entry and exit of candidates all failed to move public opinion polls during 1995. In the absence of saturation media coverage and media labeling of "winners" and "losers" in the early caucuses and primaries, few dramatic poll shifts appeared. The Republicans Throughout 1995, the Gallup Poll reported only slight changes in the first-choice preferences of self-identified Republicans and independents leaning Republicans. Between April 1995 and January 1996, front-runner Bob Dole’s support varied only from a low of 45 percent to a high of 51 percent. Support for Senator Phil Gramm varied only from a low of seven percent to a high of 13 percent. -

THE RISE of a GLOBAL PARTY? American Party Organizations Abroad

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.2 pp. 241–255 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi THE RISE OF A GLOBAL PARTY? American Party Organizations Abroad Taylor Dark III ABSTRACT In discussions of party organization, scholars have generally assumed that such organizations operate exclusively on the domestic level, seeking to alter electoral results by raising votes and money from constituencies at home. This research note shows that this assumption is outdated, because the US Democratic and Republican parties now maintain overseas branches in dozens of different countries. These branches seek through a variety of means to mobilize the votes and financial resources of Americans abroad in an attempt to change domestic political outcomes. An analysis of the rise of these groups demonstrates the value of the concept of globalization in an area where it is usually not considered relevant, and raises new normative and practical questions about how to regulate overseas political activity by US citizens and parties. KEY WORDS American politics globalization party organization One of the oldest and most resilient ways of conceptualizing political party activity has been to divide it into three components: the party in the elec- torate, the party in government and the party as an organization. The last of these components was, of course, defined in reference to the leaders and activists who worked through the party apparatus to gain members, finan- cial contributions and votes on behalf of party nominees. Naturally enough, this activity was assumed to take place entirely within the territorial bound- aries of the country where the party contested elections – American party organizations mobilized within the USA, British parties within Britain, and so on. -

To Assure Pride and Confidence in the Electoral Process

To Assure Pride and Confidence in the Electoral Process August 2001 The National Commission on Federal Election Reform Organized by Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia The Century Foundation Supported by The David and Lucile Packard Foundation The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation Miller Center of Public Affairs University of Virginia P.O. Box 400406 2201 Old Ivy Road Charlottesville VA 22904-4406 tel 804-924-7236 fax 804-982-2739 web http://millercenter.virginia.edu The Century Foundation 41 East 70th Street New York NY 10021 tel 212-535-4441 fax 212-879-9190 web http://www.tcf.org www.reformelections.org The Commission Public Hearings Honorary Co-Chairs March 26, 2001 President Gerald R. Ford Citizen Participation President Jimmy Carter The Carter Center Co-Chairs Atlanta, Georgia Robert H. Michel April 12, 2001 Lloyd N. Cutler Election Administration Vice-Chairs The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Slade Gorton Simi Valley, California Kathleen M. Sullivan May 24, 2001 Commissioners What Does the Law Require? Griffin Bell Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Museum Rudy Boschwitz Austin,Texas John C. Danforth Christopher F. Edley, Jr. June 5, 2001 Hanna Holborn Gray The American and International Experience Colleen C. McAndrews Gerald R. Ford Library Daniel Patrick Moynihan Ann Arbor, Michigan Leon Panetta Deval L. Patrick Diane Ravitch Bill Richardson John Seigenthaler Michael Steele Executive Director Philip D. Zelikow To Assure Pride and Confidence in the Electoral Process August 2001 The National Commission on Federal Election Reform Organized by Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia The Century Foundation Supported by The David and Lucile Packard Foundation The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation The John S. -

Selecting Representative and Qualified Candidates for President

Selecting Representative and Qualifed Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries Democracy and the Consttuton Clinic Fordham University School of Law Daisy de Wolf, Ben Kremnitzer, Samara Perlman, & Gabriella Weick January 2021 Selecting Representative and Qualifed Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries Democracy and the Consttuton Clinic Fordham University School of Law Daisy de Wolf, Ben Kremnitzer, Samara Perlman, & Gabriella Weick January 2021 This report was researched and writen during the 2019-2020 academic year by students in Fordham Law School’s Democracy and the Consttuton Clinic, where students developed non-partsan recommendatons to strengthen the naton’s insttutons and its democracy. The clinic was supervised by Professor and Dean Emeritus John D. Feerick and Visitng Clinical Professor John Rogan. Acknowledgments: We are grateful to the individuals who generously took tme to share their general views and knowledge with us: Robert Bauer, Esq., Professor Monika McDermot, Thomas J. Schwarz, Esq., Representatve Thomas Suozzi, and Jesse Wegman, Esq. This report greatly benefted from Gail McDonald’s research guidance and Flora Donovan’s editng assistance. Judith Rew and Robert Yasharian designed the report. Table of Contents Executve Summary .....................................................................................................................................1 Introducton .....................................................................................................................................................4 -

Andrew Coombes I Applied for the Burns Fellowship After a Work

Andrew Coombes I applied for the Burns Fellowship after a work colleague and Burns alumna spoke in glowing terms about the experience she had had in Berlin a few years previously. Having a long-held interest in the modern history of Germany, I felt that the fellowship programme would present me with an opportunity to explore some stories in depth for Al Jazeera English, my home organisation, while also giving me an insight into how German media operate through my host organisation in Germany. I felt mild trepidation after being accepted to the fellowship - I was concerned that having no German language skills would be a natural impediment to producing material, particularly when working in a German newsroom. I was therefore grateful that the Burns Fellowship offered two weeks of intensive German language training at the Goethe Institute. To those who are wary of applying to the Burns programme due to their lack of German - just apply regardless. I found the tuition offered by the Goethe instrumental in getting a feel for the German language and it also presented me with some useful insights into German society and culture. With umlauts practiced and my pronunciation of ‘entschuldigung’ well-drilled, I turned up early on a warm Monday morning at the Berlin parliamentary bureau of the Rheinische Post, who kindly agreed to be my host for the early part of my placement. A few days prior to the placement I had had a few kolsch beers with Michael Broecker, who leads the bureau, and found him to be approachable, engaged and eager to help in any way that he could. -

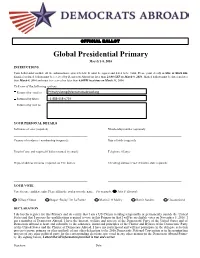

Global Presidential Primary March 1-8, 2016 INSTRUCTIONS Your Ballot Must Include All the Information Required Below

OFFICIAL BALLOT Global Presidential Primary March 1-8, 2016 INSTRUCTIONS Your ballot must include all the information required below. It must be signed and dated to be valid. Please print clearly in blue or black ink. Emailed or faxed ballots must be received by Democrats Abroad no later than 24:00 CET on March 8, 2016. Mailed ballots must be dated no later than March 8, 2016 and must be received no later than 6:00PM local time on March 13, 2016. Tick one of the following options: Returned by email to [email protected] Returned by fax to +1-888-958-6739 Returned by mail to YOUR PERSONAL DETAILS Full name of voter (required): Membership number (optional): __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Country of residence / membership (required): Date of birth (required): __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Email (if any, and required if ballot returned by email): Telephone (if any): __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Physical address overseas (required, no P.O. boxes): US voting address (exact if known, state required): __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ YOUR VOTE Vote