2 Peter Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Peter 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on 2 Peter 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable HISTORICAL BACKGROUND This epistle claims that the Apostle Peter wrote it (1:1). It also claims to follow a former letter written by Peter (3:1), which appears to be a reference to 1 Peter, although Peter may have been referring to a letter we no longer have.1 The author's reference to the fact that Jesus had predicted a certain kind of death for him (1:14) ties in with Jesus' statement to Peter recorded in John 21:18. Even so, "most modern scholars do not think that the apostle Peter wrote this letter."2 The earliest external testimony (outside Scripture) to Petrine authorship comes from the third century.3 The writings of the church fathers contain fewer references to the Petrine authorship of 2 Peter than to the authorship of any other New Testament book. It is easy to see why critics who look for reasons to reject the authority of Scripture have targeted this book for attack. Ironically, in this letter, Peter warned his readers of heretics who would depart from the teachings of the apostles and the Old Testament prophets, which became the very thing some of these modern critics do. Not all who reject Petrine authorship are heretics, however. The arguments of some critics have convinced some otherwise conservative scholars who no longer retain belief in the epistle's inspiration. "There is clear evidence from the early centuries of Christianity that the church did not tolerate those who wrote in an apostle's name. -

2 Peter 2014 Edition Dr

Notes on 2 Peter 2014 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction HISTORICAL BACKGROUND This epistle claims that the Apostle Peter wrote it (1:1). It also claims to follow a former letter by Peter (3:1) that appears to be a reference to 1 Peter, though Peter may have been referring to a letter we no longer have. The author's reference to the fact that Jesus had predicted a certain kind of death for him (1:14) ties in with Jesus' statement to Peter recorded in John 21:18. Even so, "most modern scholars do not think that the apostle Peter wrote this letter."1 The earliest external testimony (outside Scripture) to Petrine authorship comes from the third century.2 The writings of the church fathers contain fewer references to the Petrine authorship of 2 Peter than to the authorship of any other New Testament book. It is easy to see why critics who look for reasons to reject the authority of Scripture have targeted this book for attack. Ironically in this letter Peter warned his readers of heretics who departed from the teaching of the apostles and the Old Testament prophets, which is the very thing some of these modern critics do. Not all who reject Petrine authorship are heretics, however. The arguments of some critics have convinced some otherwise conservative scholars who retain belief in the epistle's inspiration. Regardless of the external evidence, there is strong internal testimony to the fact that Peter wrote the book. This includes stylistic similarities to 1 Peter, similar vocabulary compared with Peter's sermons in Acts, and the specific statements already mentioned (i.e., 1:1, 14; 3:1). -

A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. II

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. II. by Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. II. Author: Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener Release Date: June 28, 2011 [Ebook 36549] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A PLAIN INTRODUCTION TO THE CRITICISM OF THE NEW TESTAMENT, VOL. II.*** A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament For the Use of Biblical Students By The Late Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener M.A., D.C.L., LL.D. Prebendary of Exeter, Vicar of Hendon Fourth Edition, Edited by The Rev. Edward Miller, M.A. Formerly Fellow and Tutor of New College, Oxford Vol. II. George Bell & Sons, York Street, Covent Garden London, New York, and Cambridge 1894 Contents Chapter I. Ancient Versions. .3 Chapter II. Syriac Versions. .8 Chapter III. The Latin Versions. 53 Chapter IV. Egyptian Or Coptic Versions. 124 Chapter V. The Other Versions Of The New Testament. 192 Chapter VI. On The Citations From The Greek New Tes- tament Or Its Versions Made By Early Ecclesiastical Writers, Especially By The Christian Fathers. 218 Chapter VII. Printed Editions and Critical Editions. 231 Chapter VIII. Internal Evidence. 314 Chapter IX. History Of The Text. -

THE TEACHER's OUTLINE & STUDY BIBLE 2 PETER COMMENTARY the SECOND EPISTLE GENERAL of PETER INTRODUCTION »Front Matter Conte

THE TEACHER'S OUTLINE & STUDY BIBLE 2 PETER COMMENTARY THE SECOND EPISTLE GENERAL OF PETER INTRODUCTION »Front Matter Contents: Author Date To Whom Written Purpose Special Features AUTHOR: Simon Peter, the Apostle (2 Peter 1:1). However, note several facts. (Much of the following is taken from Michael Green. He makes an excellent and scholarly case for Peter's authorship.) (The Second Epistle of Peter and The Epistle of Jude. "The Tyndale New Testament Commentaries," ed. by RVG Tasker. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1968, p.13f). 1. The author is questioned by many commentators. The questioning centers primarily around external evidence such as the following two facts. ⇒ There are no direct references to the book by the earliest Christian writers. ⇒ The first person to mention Second Peter by name was Origen who lived around the middle of the third century. When all of the evidence is considered, however, it points to Peter being the author. a. The earliest church fathers do have statements that are similar to parts of 2 Peter: 1 Clement (A.D. 950), 2 Clement (A.D. 150), Aristides (A.D. 130), Valentinus (A.D. 130), and Hippolytus (A.D. 180). b. The discovery of Papyrus 72, dated in the third century, shows that 2 Peter was well known in Egypt long before. Eusebius also states that Clement of Alexandria had 2 Peter in his Bible and wrote a commentary on it. 2. 2 Peter was not fully accepted into the canon of Scripture until the middle or latter part of the fourth century. Why did it take the church so long to accept 2 Peter as part of the canon of Scripture? This can be explained by two facts. -

HARMONY of the BOOK of JUDE and 2 PETER Chul Hae Kim*

HARMONY OF JUDE & 2 PETER 20 HARMONY OF THE BOOK OF JUDE AND 2 PETER Chul Hae Kim* Many parallel passages exist among the sixty-six books in the Bible. There are many ways to approach the relationship of each of these parallel passages. The basic principle that applies to any parallel passages in the Bible is that every book of the Bible relates to each other in a certain way. Some relate in the aspect to the time of writing whether written earlier or later: the prior ones could possibly influence the one written later. Others relate in the aspect of authorship as in the case of the Pauline Epistles and Johannine Epistles. On the other hand, we could get the same “smell” from some books even though authors were different but were influenced by each other. The relationship of some parallel passages could be explained based on certain basic principles without any struggle. All the New Testament books have their origin from Old Testament books. It is not only the New Testament books that quote from the Old Testament; Old Testament Books also quote from other books within the Old Testament. 26 Some passages quote directly from the Old Testament books, but some portions of the New Testament books relate indirectly to the Old Testament. There are many ways of quoting from the Old Testament besides direct quotation. Biblical writers use various kinds of allusions: some related to verbal phrases, others in context (including the canonical context), and the rest in main themes or topics. The study of the relationship between parallel passages is worth taking. -

The Books of the New Testament

Supplementary Church School Material - Secodary The Books of the New Testament Try to memorize these! Full Name Short Name The Gospel According to Matthew Matthew The Gospel According to Mark Mark The Gospel According to Luke Luke The Gospel According to John John The Acts of the Apostles Acts The Epistle to the Romans Romans The First Epistle to the Corinthians First Corinthians The Second Epistle to the Corinthians Second Corinthians The Epistle to the Galatians Galatians The Epistle to the Ephesians Ephesians The Epistle to the Philippians Philippians The Epistle to the Colossians Colossians The First Epistle to the Thessalonians First Thessalonians The Second Epistle to the Thessalonians Second Thessalonians The First Epistle to Timothy First Timothy The Second Epistle to Timothy Second Timothy The Epistle to Titus Titus The Epistle to Philemon Philemon The Epistle to the Hebrews Hebrews The Epistle of James James The First Epistle of Peter First Peter The Second Epistle of Peter Second Peter The First Epistle of John First John The Second Epistle of John Second John The Third Epistle of John Third John The Epistle of Jude Jude The Book of Revelation Revelation Supplementary Church School Material - Primary Men chosen by God wrote down the Good News of Jesus Christ with the help of the Holy Spirit. Later, the Church decided which writings should become the “New Testament”, the second part of the Holy Bible. The first four books of the Ne w Testament are called “The Gospel” which also means “good news.” The four Gospels are: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. -

Michael Green, 2 Peter Reconsidered, 1961. London

2 Peter Reconsidered The Rev E.M.B. Green, M.A., B.D. THE TYNDALE NEW TESTAMENT LECTURE, 1960 [p.5] The Second Epistle of Peter was accepted into the Canon in the fourth century with greater hesitation than any other book. That hesitation reappeared at the Reformation when Luther accepted it, Erasmus rejected it, and Calvin was uncertain. The debate has continued, but in the last forty years opinion has hardened against its genuineness, and in many quarters the question is regarded as settled. The aim of this paper is to reconsider the problem, not because the writer has the presumption to dogmatize over a question which has puzzled the ablest heads in the Church for a thousand years, but because the arguments commonly adduced to support the current view of 2 Peter as an undoubted pseudepigraph do not appear to be as securely based as might be expected from the confidence reposed in them. These arguments turn on (i) the external attestation of the book, (ii) the relationship between 2 Peter and Jude, (iii) the contrast between its diction and that of 1 Peter, (iv) the contrast between its doctrine and that of 1 Peter, and (v) various anachronisms and contradictions. Arguments (i) and (iii) alone were used in antiquity; the remainder are of more recent origin. We shall examine these points in turn. THE EXTERNAL ATTESTATION OF 2 PETER The external attestation is inconclusive. No book in the Canon is so poorly attested among the Fathers, though, as Westcott1 shows, 2 Peter has incomparably better support for its inclusion than the best attested of the rejected books. -

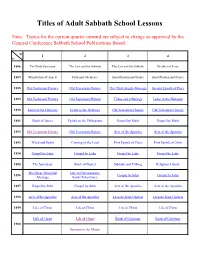

Titles of Adult Sabbath School Lessons

Titles of Adult Sabbath School Lessons Note: Topics for the current quarter onward are subject to change as approved by the General Conference Sabbath School Publications Board. Qr 1 2 3 4 Yr 1886 The Bible Sanctuary The Law and the Sabbath The Law and the Sabbath Parables of Jesus 1887 Ministration of Angels Faith and Obedience Sanctification and Prayer Sanctification and Prayer 1888 Old Testament History Old Testament History The Third Angels Message Second Epistle of Peter 1889 Old Testament History Old Testament History Tithes and Offerings Letter to the Hebrews 1890 Letter to the Hebrews Letter to the Hebrews Old Testament History Old Testament History 1891 Book of James Epistle to the Philippians Gospel by Mark Gospel by Mark 1892 Old Testament History Old Testament History Acts of the Apostles Acts of the Apostles 1893 Word and Spirit Coming of the Lord First Epistle of Peter First Epistle of John 1894 Gospel by Luke Gospel by Luke Gospel by Luke Gospel by Luke 1895 The Sanctuary Book of Daniel Sabbath and Tithing Religious Liberty The Great Threefold Life in Christ and the 1896 Gospel by John Gospel by John Message Saints' Inheritance 1897 Gospel by John Gospel by John Acts of the Apostles Acts of the Apostles 1898 Acts of the Apostles Acts of the Apostles Lessons from Genesis Lessons from Genesis 1899 Life of Christ Life of Christ Life of Christ Life of Christ Life of Christ Life of Christ Book of Galatians Book of Galatians 1900 Sermon on the Mount Book of Galatians The Sanctuary The Sanctuary Parables of Jesus 1901 Book of -

Commentarty on the Second Epistle of Peter

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY COMMENTARY COMMENTARY ON THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER by John Calvin B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 COMMENTARIES ON THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER THE ARGUMENT The doubts respecting this Epistle mentioned by Eusebius, ought not to keep us from reading it. For if the doubts rested on the authority of men, whose names he does not give, we ought to pay no more regard to it than to that of unknown men. And he afterwards adds, that it was everywhere received without any dispute. What Jerome writes influences me somewhat more, that some, induced by a difference in the style, did not think that Peter was the author. For though some affinity may be traced, yet I confess that there is that manifest difference which distinguishes different writers. There are also other probable conjectures by which we may conclude that it was written by another rather than by Peter. At the same time, according to the consent of all, it has nothing unworthy of Peter, as it shews everywhere the power and the grace of an apostolic spirit. If it be received as canonical, we must allow Peter to be the author, since it has his name inscribed, and he also testifies that he had lived with Christ: and it would have been a fiction unworthy of a minister of Christ, to have personated another individual. So then I conclude, that if the Epistle be deemed worthy of credit, it must have proceeded from Peter; not that he himself wrote it, but that some one of his disciples set forth in writing, by his command, those things which the necessity of the times required. -

The General Epistles: James, Peter, and Judas

The General Epistles: James, Peter, and Judas Author(s): Moffat, James, D.D. Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: This commentary by James Moffat takes a different form than many. Rather than analzying the text verse-by-verse, Moffat has created more of a "running" commentary. He takes generally three verses at a time, and writes a paragraph of investigaion of the original Greek, cultural notes, ect. Though Moffat©s commentaries and Bible translations are often debated because of his reliance on inaccurate arche- ological sources, his volumes are still worth reading by those concerned with having a diverse set of commentaries. Abby Zwart CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: The Bible New Testament Works about the New Testament i Contents Title Page 1 Editor’s Preface 4 The Epistle of St. James 6 Introduction 7 The Epistle of St. James 10 The First Epistle of St. Peter 54 Introduction 55 The First Epistle of St. Peter 57 The Second Epistle of St. Peter 104 Introduction 105 The Second Epistle of St. Peter 107 The Epistle of Judas 128 Introduction 129 The Epistle of Judas 136 Indexes 147 Index of Scripture References 148 Index of Scripture Commentary 153 Greek Words and Phrases 154 Latin Words and Phrases 155 French Words and Phrases 156 Index of Pages of the Print Edition 157 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. The mission of the CCEL is to make classic Christian books available to the world. • This book is available in PDF, HTML, Kindle, and other formats. -

Introduction to the Book of Second Peter

LETTERS FROM PETER 34. Is “She that is in Babylon” Peter’s wife? 35. Does “Babylon” here mean “Rome” as in Revelation? Give a reason(s) for your answer. 36. What affectionate title does Peter give Mark? 37. Identify Mark in the Book of Acts, (Was he “washed up” when he returned to Jerusalem?) 38. With what were the recipients to greet one another? 39. Upon what group does Peter wish peace? INTRODUCTION TO II PETER T I. THE RECIPIENTS. This letter is addressed “to them that have obtained a like precious faith with us” (1: 1)I More specifically, it was intended for the same people as was I Peter; i.e., “the elect who are so- journers of the Dispersion in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia” (I Pet, 1: I),for Peter himself states in 3: 1, “This is now, beloved, the second epistle that I write unto you . ,” 11. PLACE OF WRITING. It is not known, Among places conjectured have been Rome, Egypt, Palestine, and Asia. Perhaps he is still in Babylon (I Pet. 5: 13). 111. TIME OF WRITING. It is generally accepted that second Peter was written toward the end of the first century, and is one of the latest New Testa- ment books. How do we arrive at such a conclusion? a. Peter speaks of his death as near, l:14,150 b. Apparently, most or all of Paul’s epistles had already been written, 3: 15,16. c. Paul’s Epistles had existed long enough to be perverted, 3:16. His letters cover the years between 62 A.D. -

The Christian and the Law

The Christian and the law Ger de Koning Translation: J.R. Jayabalan [Original Title in German: Der Christ Und Das Gesetz] Cover design: Eva de Vlaming Layout: Ger de Koning © 2016 by Ger de Koning. All rights preserved. No part of this publication may be – other than for personal use – reproduced in any form without written permission of the author. Content Abbreviations of the Names of the Books of the Bible ...................................................... 5 Old Testament ...................................................................................................................... 5 New Testament .................................................................................................................... 6 Foreword .................................................................................................................................. 7 The Christian and the law ...................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 8 2. Not justified by law, but by faith alone ........................................................................ 9 3. The law: for Israel and the nations? ............................................................................. 10 4. Which period the law is valid? .................................................................................... 13 5. How is it possible that the Christian is no longer