Indian Status, Band Membership and Aboriginal Rights & Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qwewrt U Aboriginal Affairs and Affaires Autochtones Et Page 2 of 4 Northern Development Canada Développement Du Nord Canada Protected B (When Completed)

u Aboriginal Affairs and Affaires autochtones et Page 1 of 4 Northern Development Canada Développement du Nord Canada PRoTECTED B (When Completed) SEcURE cERTiFicaTE OF indian STaTUS (SciS) adULT aPPLicaTiOn in-canada FOR aPPLicanTS SiXTEEn (16) YEaRS OF aGE OR OLdER Privacy Act Statement Personal information provided in this document is collected by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) under the authority of the Indian Act . Individuals have the right to the protection of and access to their personal information under the Privacy Act . The information provided is voluntary. Failure to provide sufficient information may render the application invalid or may result in processing delays. Information provided is subject to routine verifications, including verifications against the Indian Register. AANDC may, for the purpose of receiving applications, collect personal information from Indian Registry Administrators. Furthermore, personal information will be disclosed to a third party for the purpose of printing the SCIS. In the performance of these duties, personal information will be processed and used in accordance with the provisions of the Privacy Act . Further details on the collection, use and disclosure of personal information are described under the Personal Information Bank INA PPU 110, which is detailed at www.infosource.gc.ca . Helpful Tips for completing Your SciS application complete and sign pages 3 and 4 of the application. FaiLURE TO cOMPLETE aLL THE SEcTiOnS OF THiS FORM and SUBMiT aLL nEcESSaRY dOcUMEnTaTiOn WiLL RESULT in YOUR aPPLicaTiOn BEinG REFUSEd and RETURnEd TO YOU. Personal information (Section A) If the name written in Section A differs from that on your birth certificate or identification documents, the following original documents may be required: adoption order, legal name change, marriage certificate or other court document. -

16 Years of Age Or Older.Pdf

Métis Nation of Alberta Métis Nation Registry #100 Delia Gray Building 11738 Kingsway Avenue 16 YEARS OF AGE OR OLDER Edmonton AB T5G 0X5 Phone: (780) 455-2200 Toll Free: 1-866-678-7888 Application for Métis Nation of Alberta Membership GENERAL INFORMATION AND INSTRUCTIONS Failure to complete all the required sections of this form will result in your application being returned to you. Entitlement to a Métis Nation of Alberta Membership Requirements Checklist “Métis” – a person who self identifies as Métis, is distinct A completed genealogy (family tree) which clearly outlines from other Aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation your Métis ancestry to the mid 1800’s. ancestry and is accepted by the Métis Nation. Copy of ONE of the following: o Live Birth Registration A Métis must provide historical proof of his or her status as o Long Form Birth Certificate showing the full names of Métis: biological parents o Wallet-size birth certificate PLUS copy of baptismal a) Historic Proof – evidence of an ancestor who received a certificate with church seal (legible) and officiates land grant, or a scrip grant under the Manitoba Act or the signature Dominion Lands Act, or who was recognized as a Métis in One (1) piece of current photo identification other government, church or community records; Proof of permanent residency in Alberta for a minimum of b) Historic Métis Nation means the Aboriginal people then ninety (90) consecutive days may be required. known as Métis or Half-Breeds who resided in historic Métis Nation Homeland; c) Historic Métis Nation Homeland means the area of land in Additional documents or information may be requested west central North America used and occupied as the in support of this application traditional territory of the Métis or Half-Breeds as they were then known. -

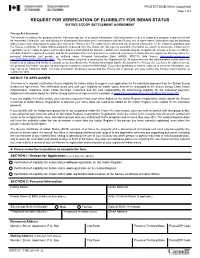

Request for Verification of Eligibility for Indian Status Sixties Scoop Settlement Agreement

PROTECTED B (When Completed) Page 1 of 8 REQUEST FOR VERIFICATION OF ELIGIBILITY FOR INDIAN STATUS SIXTIES SCOOP SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT Privacy Act Statement This statement outlines the purposes for the collection and use of personal information. Only information needed to respond to program requirements will be requested. Collection, use, and disclosure of personal information are in accordance with the Privacy Act. In some cases, information may be disclosed without your consent pursuant to subsection 8(2) of the Privacy Act. The authority to collect and use personal information for the Indian Registration and the Secure Certificate of Indian Status programs is derived from the Indian Act. We use the personal information we collect to determine entitlement to registration on the Indian Register and membership in a First Nation for which the Band List is maintained by the Department, to issue a Secure Certificate of Indian Status to registered persons, and for the provision of benefits and services conferred exclusively to those who are registered. We may share the personal information you provide as outlined under Personal Information Bank AANDC PPU110 (Info Source www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/ eng/1100100011039/1100100011040). The information collected is retained by the Department for 30 years after the last administrative action and then transferred to Library and Archives Canada (or as described in the Personal Information Bank). As stated in the Privacy Act, you have the right to access the personal information you give us and request changes to incorrect information. If you have questions or wish to notify us of incorrect information, you may call us at 1-800-567-9604. -

Indigenous Cultural Understanding Framework (ICUF) Began This Work in Ceremony

January 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................................................................. 5 Beginning the Journey in Ceremony ........................................................................................ 5 Our Elders tell us… .................................................................................................................. 6 A Living Framework .................................................................................................................. 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 Reconciliation ........................................................................................................................... 7 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 7 It Begins and Ends with Each One of Us ................................................................................. 8 OUR VISION ................................................................................................................................... 8 PRINCIPLES .................................................................................................................................... 9 Reconciliation: Moving Forward Together ................................................................................ 9 Respect: Open Minds, Open Hearts ....................................................................................... -

An Act Respecting Membership

CANADA’S COLLABORATIVE PROCESS ON INDIAN REGISTRATION REFORMS AN ACT RESPECTING MEMBERSHIP LEGAL AFFAIRS AND JUSTICE CANADA’S COLLABORATIVE PROCESS ON INDIAN REGISTRATION REFORMS DISCUSSION PAPER – Assembly of First Nations February 19, 2019 Table of Contents I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Historical background ..................................................................................................................................................................2 A. “Phase 2” is introduced for the third time since 1985 ..........................................................................................................2 B. Lax policies make it easier for the Crown to accept surrenders ..........................................................................................2 III. Present-day rules governing the Indian Act ...................................................................................................................3 A. The effective blood quantum rule ...........................................................................................................................................3 1. Before 1985: Status was conditional on the male line ......................................................................................................3 2. After 1985 ...............................................................................................................................................................................4 -

Métis and Non-Status First Nations Land Claims. Contemporary Issues Métis and First Nation People Without

Walking Together: First Nations, Métis and Inuit Perspectives in Curriculum Aboriginal and Treaty Rights MÉTIS AND NON-STATUS FIRST NATIONS LAND CLAIMS Excerpt from Contemporary Issues MÉTIS AND NON-STATUS FIRST NATIONS LAND CLAIMS Métis and First Nations People without status make up a significant proportion of Canada‟s Aboriginal Populations. Many of these people grapple with economic and social hardships in the midst of a society that views them as neither Aboriginal nor part of the mainstream society. NON-STATUS LAND CLAIMS ISSUES Most Aboriginal leaders dispute the government‟s right to legislate who does and does not belong to various groups of Aboriginal people. They wonder why, for example, someone cannot claim their Aboriginal ancestry and the rights that accompany that ancestry simply because his or her great-great-grandfather decided to accept scrip. They wonder why someone is denied rights because of who his or her mother or grandmother decided to marry. They point to people like Stephen Kakfwi. This prominent Dene leader, a former premier of the Northwest Territories, is the son of two full-blooded Dené Tha‟ parents. However, because his grandfather gave up his status to own property and open a business, Stephen Kakfwi is officially considered a non-Status Indian by the federal government. When the federal government passed the Indian Act in 1876, it had to decide to whom that law would apply. It decided that, for the purposes of the act, an Indian was “Any male person of Indian blood reputed to belong to a particular band; any child of such person; any woman who is or was lawfully married to such person.” By defining who would be considered an Indian, the government also decided who would not be considered one. -

The Original Intentions of the Indian Act

THE ORIGINAL INTENTIONS OF THE INDIAN ACT These materials were prepared by Joan Holmes, Joan Holmes & Associates Inc., Ottawa for a conference held in Ottawa, Ontario hosted by Pacific Business and Law Institute, April 17-18, 2002. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................3. II. THE ROLE AND PLACE OF TREATIES...............................................................5. III. THE HISTORIC ROOTS OF THE INDIAN ACT...................................................7. A. THE EARLY RELATIONSHIP AND SETTLEMENT PLANS......................7. B. INVESTIGATIONS INTO INDIAN AFFAIRS AND THE INDIAN DEPARTMENT...............................................................................................12. C. PRE-CONFEDERATION LEGISLATION: MEMBERSHIP, LANDS AND GOVERNANCE MODELS ..................................................................16. IV. HAS THE INDIAN ACT FAILED?..........................................................................28. V. CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................................30. BIBLIOGRAPHY..................................................................................................................31. I. INTRODUCTION For over a century the Indian Act has held great symbolic and practical importance. Both ambiguous and ubiquitous it has been reviled as a "symbol of discrimination, a piece of racist legislation" and at the same time been protected and depended -

LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES in the AMERICAS: Subclasses KIA-KIP North America: Introduction

LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE AMERICAS: Subclasses KIA-KIP North America: Introduction Prospecting a new Class for the American Indigenous peoples. The new classification schedule on Law of the Indigenous Peoples in the Americas (Classes KIA-KIP: North America), currently in draft stage, is a subclass of the Library of Congress Classification( LCC), Class K (Law), and will conclude for the time being the regional/comparative law classification schedule for the Americas, Classes KDZ-KIX. Emerging project. The various stages of research for subject classification of the initial classes KIA-KIK, and the “sifting” of the Web have revealed that the critical mass of resources, in particular primary sources produced by the individual Aboriginal or tribal governments, and the output of their organizations or inter-operational institutions, together with the secondary literature, are mainly to be found on the Web – dispersed, unorganized, and for that matter, obscure. To this date, however, both information seekers and information providers are hard pressed by an uneasy reality: the obvious gap between availability and accessibility of information. Search and research are still confronted with problems, such as < paucity of (commercial) printing/publishing of current legal materials; < collections on law and sociology of Indigenous peoples, one of a kind and mostly little publicized, are held only by a few bona fide and specialist institutions; < programs with limited access; or < information on the subject which may be buried in relevant anthropological, archeological, or ethnological sources, usually in older collections on the History of the Americas. And, to this point, even < Class KF (Law of the United States), the only place in the LCC which has a section on American Indian law and law-related materials (KF8220+), does not reflect the sovereign status and autonomy of the Indian nations, nor does it reflect current Indian law making and law developments. -

The Debate About Métis Aboriginal Rights—Demography, Geography, and History

The Debate about Métis Aboriginal Rights— Demography, Geography, and History Tom Flanagan 2017 2017 • Fraser Institute The Debate about Métis Aboriginal Rights—Demography, Geography, and History by Tom Flanagan fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive summary / ii Preliminary note on terminology / iv Introduction / 1 Demography and Destiny / 3 The Age of Extinguishment / 8 Ambiguous Entrenchment / 10 Implications / 14 Conclusions / 24 References / 26 About the author / 30 Acknowledgments / 30 Publishing Information / 31 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 32 Purpose, Funding, and Independence / 32 About the Fraser Institute / 33 Editorial Advisory Board / 34 fraserinstitute.org ii x The Debate about Métis Aboriginal Rights x Flanagan Executive summary In the 2015 federal election campaign, the Liberal Party promised to engage in “nation to nation” negotiations with the “Métis Nation” to establish Métis self- government and to settle unresolved land claims. Discussions are now under way with the provincial affiliates of the Métis National Council in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario. Success, however, will be difficult to attain for reasons of demog- raphy, geography, and history. According to the census, the Métis population has grown explosively, from 178,000 in 1991 to 418,000 in 2011. Most of this growth is not from natural increase but from “ethnic mobility,” that is, people adopting new labels for them- selves when they answer census questions. As a result of this particular form of population growth, social and economic indicators for the self-identified Métis population are now converging with Canadian averages. At the same time, the category of non-status Indians, which overlaps with the Métis, has grown even faster, from 87,000 in 1991 to 214,000 in 2011. -

Not Strangers in These Parts | Urban Aboriginal Peoples

Not Strangers in These Parts “Canada’s urban Aboriginal population offers the potential of a large, young and growing population — one that is ambitious and increasingly skilled. Let us work together to “ensure that urban Aboriginal Canadians are positioned and empowered to make an ongoing contribution to the future vitality of our cities and Canada.” Not Strangers in These Parts The Honourable Ralph Goodale, P.C., M.P. Urban Aboriginal Peoples Federal Interlocutor for Métis” and Non-Status Indians Lead Minister for the Urban Aboriginal Strategy Presentation to the Expanding Prairie Horizons – 2020 Visions Symposium, Winnipeg, Manitoba, March 7, 2003 70 % | 0 % Urban Aboriginal Peoples Percent Distribution of Aboriginal People in Winnipeg – 2001 Edited by David Newhouse & Evelyn Peters Not Strangers in These Parts Urban Aboriginal Peoples Edited by David Newhouse & Evelyn Peters CP22-71/2003 ISBN 0-662-67604-1 Table of Contents Preface . .3 Acknowledgements . 4 Introduction . 5 Urban Aboriginal Populations: An Update Using 2001 Census Results . 15 Definitions of Aboriginal Peoples . 20 The Presence of Aboriginal Peoples in Quebec’s Cities: Multiple Movements, Diverse Issues . 23 Fuzzy Definitions and Population Explosion: Changing Identities of Aboriginal Groups in Canada . 35 Aboriginal Mobility and Migration Within Urban Canada: Outcomes, Factors and Implications . 51 Urban Residential Patterns of Aboriginal People in Canada . 79 Aboriginal Languages in Canada’s Urban Areas: Characteristics, Considerations and Implications . 93 The Challenge of Measuring the Demographic and Socio-Economic Conditions of the Urban Aboriginal Population . 119 The Marginalization of Aboriginal Women in Montréal . 131 Prospects for a New Middle Class Among Urban Aboriginal People . 147 Ensuring the Urban Dream: Shared Responsibility and Effective Urban Aboriginal Voices . -

The Residential School System in Canada: Understanding the Past – Seeking Reconciliation – Building Hope for Tomorrow

TEACHER’S GUIDE The Residential School System in Canada: Understanding the Past – Seeking Reconciliation – Building Hope for Tomorrow Second Edition Second Edition ©2013 Government of Northwest Territories, Government of Nunavut, and the Legacy of Hope Foundation This resource was developed and published by the Design and Production: following Partners: NationMedia + Design, Legacy of Hope Foundation Department of Education, Culture and Employment, Government of Northwest Territories P.O. Box 1320 ISBN: Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 978-0-7708-0206-6 Phone: 867-873-7176 Reproduction, in whole or in part, of this document for Fax: 867-873-0109 personal use and in particular for educational purposes, www.ece.gov.nt.ca is authorized, proived the following conditions are respected: non-commercial distribution; respect of the document's integrity (no modification or alteration of Department of Education, Government of Nunavut any kind); and a clear acknowledgement of its source P.O. Box 1000, Station 910 as follows: 2nd Floor, Sivummut Building Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 Residential School System in Canada: Understanding Phone: 867-975-5600 the Past – Seeking Reconciliation – Building Hope for Fax: 867-975-5605 Tomorrow. Department of Education, Culture and www.gov.nu.ca Employment (GWNT), Department of Education (GN), Legacy of Hope Foundation, 2013. Legacy of Hope Foundation Unauthorized use of the name and logo of the 75 Albert Street, Suite 801 Governments of The Northwest Territories and Nunavut, Ottawa, ON K1P 5E7 and the Legacy of Hope Foundation is prohibited. Phone: 613-237-4806 or toll-free: 877-553-7177 The Partners wish to acknowledge the support of the Fax: 613-237-4442 following institutions: www.legacyofhope.ca The Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre; and Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Cover Images 1. -

The Government's Role in Deciding Indian Status and Band Membership

THE GOVERNMENT'S ROLE IN DECIDING INDIAN STATUS AND BAND MEMBERSHIP LEGAL AFFAIRS AND JUSTICE THE GOVERNMENT'S ROLE IN DECIDING INDIAN STATUS AND BAND MEMBERSHIP The Continued role of the Federal Government in Determining Indian Status and Band Membership What is Canada’s current role? They can get control over their band list through an application The Government of Canada keeps the record of who has federal and creation of a membership code or rules. These must be Indian status. Federal Indian status is decided through the appli- approved by the Minister, as noted in the Indian Act. Find out more cation of sections 6(1) and 6(2) of the Indian Act. Status Indians by reading the First Nations’ Authorities to Determine Band Mem- have access to certain entitlements and programs, such as: tax bership Fact Sheet. exemptions for income earned on-reserve and for federal sales tax; access to non-insured health benefits; access to post-sec- The Government’s new role in deciding ondary education funding. It is also linked to Treaty rights, and Indian status and band membership to Aboriginal rights. On August 28, 2017, the Government of Canada announced the creation of two departments: The purpose of Indian registration is to let the Government clearly identify who is entitled to federal programs and funding. • Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) Indian Register The Federal Government’s official record of all status Indians • Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) is called the Indian Register. The Indian Registrar is responsible for keeping a list of all individuals with Indian Status, as well as These departments replace the Department of Indigenous and new registrations resulting from births, adoptions, etc.