Father Damien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

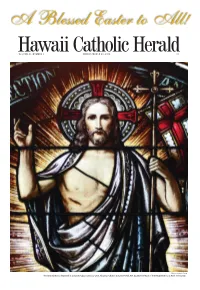

The Risen Christ Is Depicted in a Stained-Glass Window at St

A Blessed Easter to All! HVOLUME 81,awaii NUMBER 6 CatholicFRIDAY, MARCH 23, 2018 Herald$1 CNS photo/Gregory A. Shemitz The risen Christ is depicted in a stained-glass window at St. Aloysius Church in Great Neck, N.Y. Easter, the feast of the Resurrection, is April 1 this year. 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • MARCH 23, 2018 Hawaii Catholic Herald Newspaper of the Diocese of Honolulu Founded in 1936 Published every other Friday PUBLISHER Bishop Larry Silva (808) 585-3356 [email protected] EDITOR Patrick Downes (808) 585-3317 [email protected] REPORTER/PHOTOGRAPHER Darlene J.M. Dela Cruz (808) 585-3320 [email protected] ADVERTISING Shaina Caporoz (808) 585-3328 [email protected] CIRCULATION Donna Aquino (808) 585-3321 [email protected] HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD The risen Christ (ISSN-10453636) Periodical postage paid at Honolulu, Hawaii. Published ev- is depicted in ery other week, 26 issues a year, by the this 16th-century Roman Catholic Church in the State of painting titled Hawaii, 1184 Bishop Street, Honolulu, HI “Christ Risen 96813. From the Tomb ONE YEAR SUBSCRIPTION RATES and two Saints” Hawaii: $24 Mainland: $26 by Moretto da Mainland 1st class: $40 Brescia. Foreign: $30 CNS/Bridgeman Images POSTMASTER Send address changes to: Hawaii Catholic Herald, 1184 Bishop Street, Honolulu, HI 96813. OFFICE Official notices Hawaii Catholic Herald 1184 Bishop St. Bishop’s calendar March 29, 7:00 pm, Holy Thursday Eve- day, Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, Honolulu, HI 96813 Bishop’s Schedule [Events indicated will be ning Mass of the Lord’s Supper, Co-Cathedral downtown Honolulu. -

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’S Back to the Islands Special Liturgy to Mark Priests Navigate Why Didn’T for Incoming Head of 75Th Anniversary of the U.S

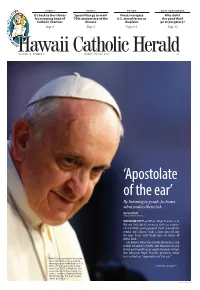

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’s back to the Islands Special liturgy to mark Priests navigate Why didn’t for incoming head of 75th anniversary of the U.S. armed forces as the good thief Catholic Charities diocese chaplains go to purgatory? Page 3 Page 5 Page 8-9 Page 12 HVOLUME 79,awaii NUMBER 14 CatholicFRIDAY, JULY 29, 2016 Herald$1 ‘Apostolate of the ear’ By listening to youth, he hears what makes them tick By Carol Glatz Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY — When Pope Francis is in Poland July 26-31 to meet with an expect- ed 2 million young people from around the world, he’s there with a firm idea of the dreams, fears and challenges so many of them face. He knows what lies inside the hearts and minds of today’s youth, not because of any third-party polling or sophisticated survey, but because Pope Francis practices what he’s called an “apostolate of the ear.” Pope Francis is pictured leaving an encounter with young people in the piazza outside the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Assisi, Italy, Continued on page 10 in this Oct. 4, 2013, file photo. The pope plans to visit Assisi Aug. 4 to make a “simple and private” visit to the Portiuncola, the stone chapel rebuilt by St. Francis. CNS photo/Paul Haring 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • JULY 29, 2016 Official notices Hawaii Bishop’s calendar Bishop’s Schedule [Events indicated will be attended by Bishop’s Catholic delegate] Herald July 25-31, World Youth Day, Kraków, Poland. -

Feast of Saint Damien Alika Cullen 2018 Ka Ohana O Kalaupapa

Special Thanks The Military and Hospitaller Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem Most Reverend Larry Silva Bishop of Hawaii Father Patrick Killilea SS.CC. Sister Alicia Damien Lau OSF Grand Commandery of the West Father Gary Secor Feast of Saint Damien Alika Cullen 2018 Ka Ohana o Kalaupapa Erika Stein - NPS Kalaupapa Pat Boland – Damien Tours Ivy & Boogie Kahilihiwa Mele & Randall Watanuki Gloria Marks Mikes Catering Ed Lane – Seawind Tours Father William Petrie S.S.C.C W e l c o m e Event Schedule May 10, 201 8 H onolu lu 10:00 a.m. Damien Observance (Optional) 1:30 p.m. Pearl Harbor Admirals Barge (Optional) Tbd Damien Mass Our Lady of Peace Basilica May 11, 201 8 H onolu lu 1 p.m. St. Patrick Monastery Visit the personal relics and effects of St. Father Damien 2:30 p.m. Tour of Palace and Capitol 4 – 6 p.m. Reception 6:30 p.m. Dinner & Cocktails Pearl Harbor (Optional) May 12, 201 8 Kalaupapa Molokai 7:00 a.m. Begin Departures to Molokai 8:00 a.m. Begin Damien Tours The Saint Lazarus Field Trip to Kaluapapa is a rare 10:00 a.m. Service at St. Philomena opportunity to both visit the community of Saint Father Damien and to join his parish in the 12:30 p.m. Luau McVeigh Hall celebration of his annual Feast Day. Then, on 1:30 p.m. Service at St. Elizabeth Sunday, we will attend a second special church 3:00 p.m. Begin Departures service honoring Saint Father Damien and Saint May 13, 201 8 H onolu lu Mas s Marianne in Honolulu. -

Footsteps of American Saints Activities

Answers to Requirements Frequently Asked Questions Footsteps of 1) Heppenheim, Germany on January 23, 1838 May only Catholics or Scouts earn this? American Saints (www.americancatholic.org) Who may earn this activity patch? 2) Sisters of St. Francis in Syracuse, New York; St. Any youth or adult may earn any of the activity John Neumann (www.americancatholic.org)) patches. The requirements are grade-specific. 3) St. Joseph’s Hospital. It was the only hospital in Is this activity considered a religious Syracuse that cared for people regardless of race or emblem and may a Scout receive a religious religion. (www.americancatholic.org)) knot after earning this activity? 4) To Hawaii where she helped to greatly improve No. This activity is considered a religious activity, housing and care for lepers. She also helped to not a religious emblem. Scouts may not receive a found a home for the daughters of patients who religious knot for earning any of the activity lived in the colony. (www.americancatholic.org)) patches. 5) January 23 (www.americancatholic.org)) Will there be more Saint Activity Patches? 6) Father Damien of Moloka'i (Blessed Damien Yes. There may be additional Saint patches DeVeuster) (www.americancatholic.org)) released, from time to time. Who may serve as an adult mentor for this activity? Any parent or adult who meets the standard BSA and diocesan safe environment requirements. Mother Marianne Cope Is there any time requirement? Activity Patch Only that the grade-specific requirements need to be completed while in the respective grade level. Do the answers need to be submitted? No. -

22, 2017 Hawai'i Convention Center

2017 DAMIEN AND MARIANNE CATHOLIC CONFERENCE October 20 – 22, 2017 Hawai’i Convention Center CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Friday, October 20 Saturday, October 21 Sunday, October 22 Exhibit Hall Open Registration Check-in Registration Check-In 8:00am 7:00am 7:30am Registration Check-In Exhibit Hall Open Exhibit Hall Open Opening Ceremony 10:00am 8:30am Tongan Mass 8:30am Rosary Keynote Speaker 10:30am 10:00am Keynote Speaker 9:00am Keynote Speaker Lunch Break 12:15pm 11:15am Breakout Sessions 10:30am Performing Arts Play Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 12:30pm 12:15pm Lunch Break 12:15pm Lunch Break Reconciliation Prayer Service – Divine Mercy Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 3:00pm 12:30pm 1:00pm Closing Mass Chaplet Reconciliation Welcome from Bishop Larry Silva 1:45pm & 3:45pm Breakout Sessions Hawaiian Mass 3:00pm Dinner Break 5:00pm 4:00pm Dinner Break Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 5:00pm 4:00pm Reconciliation Reconciliation Keynote Speaker 7:00pm 7:15pm Breakout Sessions Youth Activities 8:00pm 8:30pm Concert Conference Sessions and Prayer Service Friday, October 20 10:00am 3:00pm – 5:00pm OPENING CEREMONY & SAINTS AWARD DIVINE MERCY CHAPLET Oli Prayer acknowledging Ke Akua, those who are present, and the In 1935, St. Faustina received a vision of an angel sent by God to reason for the gathering. chastise a certain city. She began to pray for mercy, but her prayers were powerless. Suddenly she saw the Holy Trinity and felt the 10:30am – 11:30am power of Jesus’ grace within her. At the same time she found P101 EXTRAORDINARY VISIONS! herself pleading with God for mercy with words she heard interiorly. -

Catholic Response to Orlando: Pray, Act, Show Solidarity Page 10

hawaii HAWAII WORLD HAWAII Altar boy to priest: A time to serve, a time Pope Francis questions Sister sisters: religious Kauai native ready to retire: Holy Trinity validity of many callings took them in for ordination pastor steps down marriages today different directions Page 3 Page 5 Page 11 Page 12 HVOLUME 79,awaii NUMBER 12 CatholicFRIDAY, JULY 1, 2016 Herald$1 Catholic response to Orlando: Pray, act, show solidarity Page 10 CNS photo/Karen Callaway, Catholic New World A memorial featuring the photos of the victims of the June 12 mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., are seen at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Chicago June 19. 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • JULY 1, 2016 Hawaii Catholic Herald Newspaper of the Diocese of Honolulu Founded in 1936 Happy Published every other Friday Feast Day PUBLISHER Bishop Larry Silva July 9 is the feast of (808) 585-3356 Our Lady of Peace. [email protected] Faithful are invited to EDITOR celebrate the day by Patrick Downes attending Mass at the (808) 585-3317 Cathedral Basilica of [email protected] Our Lady of Peace in REPORTER/PHOTOGRAPHER downtown Hono- Darlene J.M. Dela Cruz (808) 585-3320 lulu, where the iconic [email protected] gilded statue of the ADVERTISING patroness of the Shaina Caporoz Diocese of Honolulu (808) 585-3328 greets visitors on the [email protected] mauka side of the CIRCULATION church. Donna Aquino (808) 585-3321 HCH file photo [email protected] HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD (ISSN-10453636) Periodical postage paid at Honolulu, Hawaii. Published ev- ery other week, 24 issues a year, by the Roman Catholic Church in the State of Heralding back Hawaii, 1184 Bishop Street, Honolulu, HI NEWS FROM PAGES PAST 96813. -

Select Bibliography

select bibliography primary sources archives Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archive of the Archbishop of Mechelen), Brussels, Belgium. Archive at St. Anthony Convent and Motherhouse, Sisters of St. Francis, Syracuse, NY. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Honolulu. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Leuven, Belgium. Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. kalaupapa manuscripts and collections Bigler, Henry W. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cannon, George Q. Journals. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cluff, Harvey Harris. Autobiography. Handwritten copy. Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Decker, Daniel H. Mission Journal, 1949–1951. Courtesy of Daniel H. Decker. Farrer, William. Biographical Sketch, Hawaiian Mission Report, and Diary of William Farrer, 1946. Copied from the original and housed in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Gibson, Walter Murray. Diary. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Green, Ephraim. Diary. Microfilm copy, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Halvorsen, Jack L. Journal and correspondence. Copies in possession of the author. Hammond, Francis A. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Hawaii Mission President’s Records, 1936–1964. LR 3695 21, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Haycock, D. Arthur. Correspondence, 1954–1961. Courtesy of Lynette Haycock Dowdle and Brett D. Dowdle. “Incoming Letters of the Board of Health.” Hansen’s Disease. -

Supreme Court of Nova Scotia Between

2018 Yarmouth S. C. No.__________ Supreme Court of Nova Scotia Between: Jean-Michel Blinn Plaintiff and St. Mary’s Church Parish Council, The Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of Yarmouth, The Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of Halifax Defendant Page 01 – cover page (January 1st 2018, 101 pages 47531 words) Page 02 – intent of litigation Page 03 – notice of action Page 04 – notice of action (cont.) Page 05 – notice of action (cont.) Page 06 – statement of claim Page 07 – letter re: action Page 08 – affidavit of complaint Page 09 – anti-Semitism Page 10 – anti-Semitism (cont.) Page 11-20 – preliminary evidence Page 21 – letter to parishioner Page 22-28 – Dec 8th 2017 case in favour of the demolition Page 29 – Letter of demand Page 30-85 Expository Evidence Page 86 – indictment Page 87 – indictment (cont.) Page 88 – interrogatories Page 89-101 – submissions, facts, relevant case law and arguments 2018 Yarmouth S. C. No.__________ Supreme Court of Nova Scotia Between: Jean-Michel Blinn Plaintiff and St. Mary’s Church Parish Council, The Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of Yarmouth, The Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of Halifax Defendant NOTICE OF INTENT OF LITIGATION To: St. Mary’s Church Parish Council, The Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of Yarmouth The Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation of Halifax Litigation is intended against you The plaintiff intends litigation against you. The included proposed litigation is a class action suit. Order against you is sought for damages An attached draft notice of motion and statement of claim outlines the damages against the plaintiff. Judgment against you if you do not defend The court may grant an order for the relief claimed without further notice, unless you file the notice of defence before the deadline. -

Linda Lehman Receives the Damien-Dutton Award for 2014

LINDA LEHMAN RECEIVES THE DAMIEN-DUTTON AWARD FOR 2014 The International Leprosy Association is proud to announce that Linda Lehman OTR/L, MPH, C.Ped has been selected to receive the prestigious Damien-Dutton Award for 2014. Lehman has been selected for making a significant and lasting contribution to the global fight against leprosy. For more than three decades, she has travelled the world providing technical expertise and training on prevention of disability to everyone from ministries of health to community health workers. The award was created by the Damien-Dutton Society for Leprosy Aid, Inc., a non- profit organization dedicated to ridding the world of leprosy. It is named after both Father Damien, a Belgian priest, canonized in 2009 for the care he gave to people affected by leprosy on the island of Molokai, Hawaii, and after Joseph Dutton, a U.S. civilian war veteran, who helped Father Damien. Every year since 1953, the Damien-Dutton Society has presented an award to a notable person who has made a significant contribution towards the conquest of leprosy. Past award recipients include John F. Kennedy (posthumously), Dr Paul and Dr Margaret Brand and Mother Teresa. American Leprosy Missions received the award in 1981. An American Leprosy Missions’ Senior Advisor for Morbidity Management & Disability Prevention, Ms. Lehman is trained as an occupational therapist, has a Master of Public Health degree from Emory University and a certification in pedorthics. She has developed training materials endorsed by the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP). Linda Lehman has strong links with Brazil and its National Leprosy Control Program where she served as advisor in her field of expertise for several years. -

The Kamehameha Statue

The Kamehameha Statue Jacob Adler In the Hawaiian legislature of 1878, Walter Murray Gibson, then a freshman member for Lahaina, Maui, proposed a monument to the centennial of Hawaii's "discovery" by Captain James Cook. Gibson said in part: Kamehameha the Great "was among the first to greet the discoverer Cook on board his ship in 1778 . and this Hawaiian chief's great mind, though [he was] a mere youth then, well appreciated the mighty changes that must follow after the arrival of the white strangers." After reviewing the hundred years since Cook, Gibson went on: And is not this history at which we have glanced worthy of some commemoration? All nations keep their epochs and their eras. ... By commemorating notable periods, nations renew as they review their national life. Some would appreciate a utilitarian monument, such as a prominent light- house; others, a building for instruction or a museum; and I highly appreciate the utilitarian view, yet I am inclined to favor a work of art. And what is the most notable event, and character, apart from discovery, in this century, for Hawaiians to com- memorate? What else but the consolidation of the archipelago by the hero Kamehameha? The warrior chief of Kohala towers far above any other one of his race in all Oceanica. Therefore . lift up your hero before the eyes of the people, not only in story, but in everlasting bronze.1 The legislature appropriated $10,000, and appointed a committee to choose the monument and carry out the work: Walter M. Gibson, chairman; Archibald S. -

Hawaiian Islands

THE KANAKA AND THEIR ISLES OF SANDWICH And yet — in fact you need only draw a single thread at any point you choose out of the fabric of life and the run will make a pathway across the whole, and down that wider pathway each of the other threads will become successively visible, one by one. — Heimito von Doderer, DIE DÂIMONEN HDT WHAT? INDEX HAWAIIAN ISLANDS SANDWICH ISLANDS “Sandwich Islanders” in Chapter 1, paragraph 3a of WALDEN: Henry Thoreau referred to the Kanaka under the name currently in use in New England: WALDEN: I would fain say something, not so much concerning the Chinese and Sandwich Islanders as you who read these pages, who are said to live in New England; something about your condition, especially your outward condition or circumstances in this world, in this town, what it is, whether it is necessary that it be as bad as it is, whether it cannot be improved as well as not. I have travelled a good deal in Concord; and every where, in shops, and offices, and fields, the inhabitants have appeared to me to be doing penance in a thousand remarkable ways. What I have heard of Brahmins sitting exposed to four fires and looking in the face of the sun; or hanging suspended, with their heads downward, over flames; or looking at the heavens over their shoulders “until it becomes impossible for them to resume their natural position, while from the twist of the neck nothing but liquids can pass into the stomach;” or dwelling, chained for life, at the foot of a tree; or measuring with their bodies, like caterpillars, the breadth of vast empires; or standing on one leg on the tops of pillars, –even these forms of conscious penance are hardly more incredible and astonishing than the scenes which I daily witness. -

Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time

!%JR:75()H QGV`(5( ( ! TwentyTwenty----NinthNinth Sunday in Ordinary Time Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 21, 2018 Saint Andrew the Apostle Parish Page 2 Stewardship is a way of life. Today, October 21, 2018 Tithing is God’s Plan for Giving : World Mission Sunday October 7, 2018 CCD Classes Tithing Income $8,108.10 9:30-10:45am for Kindergarten—High School Tithe $ 810.81 10:50 thru 11am Mass for 3yr & 4yr Preschool $7,297.29 Online $ 752.00 R.C.I.A —Monday, October 22, 7:00—8:30pm, School Multipurpose Room Actual Income $8,049.29 Weekly Budget $7,500.00 Bible Study —Tuesday, October 23, 9:00—11:00 am and 6:30—8:30 pm both in the Parish Meeting Room. Poor Box $ 42.50 Next Weekend, October 27/28, 2018 Children’s Offerings $ 2.00 CCD Classes—Sunday 9:30-10:45am for Kindergarten—High School This week: 10/21: For the Family 10:50 thru 11am Mass for 3yr & 4yr Preschool of Garrett Seech, Christina Youth Group Soup Sales – after Masses in School hall Sentelle, Anna Marie Pickert; Kathaleen Bryan, Keith Wolfrey, Aliene Minister Schedule Misitis, Kellie Reiber, Philip Baker, Fred Eisenhart , Tom Lopresti, Frank Lago, If you are unable to serve, please find a substitute. Thank you. Adele Hanson, Gretchen Bertuccini , Chauney McGarney, Zoey Walker , Perry Saturday, October 27, 5pm: Fath, Lisa White, James J. Thomas, Cathy Kinman, Ed EMHC —Mike Geoffroy, Carmen Krawczak, Janet Bryner, Earl Bennett, Ty Long, Robin L. Fraley , Robin Stockton, 1 Needed ; Altar Servers —Ben Holderness, Gordon Fath, Jr., A Special Intention for Williams, Caiden