Cholera Surveillance During the Haiti Epidemic — the First 2 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Male Heroism, Demonic Pigs, and Memories of Violence in the Haitian-Dominican Borderlands1

CELEBRATING 25 YEARS! MAY10 by LAUREN (Robi N ) D E R by CSW Male Heroism, Demonic Pigs, and Memories of Violence in the Haitian-Dominican Borderlands1 1 MAY 10 MAY 10 Community Building, 21st Century style! During Women’s History Month, Gloria hot-button issues. In “Climates, Clocks, and In an interview in this month’s issue, Steinem remarked, “If I could have one wish Kids,” graduate students and faculty shared Lucy Burns praises CSW’s support: “CSW has for the women’s movement worldwide, it their experiences making critical decisions been incredibly committed to junior fac- would be to have feminist groups every- about family planning, career timelines, ulty, especially junior faculty of color. I have where. We’re communal creatures. We need and the impacts of institutional climates. benefited greatly from that…. In my time to gather together once a week or once a Participants talked of networks of very close as an Assistant Professor here at UCLA, CSW month and discover we’re not alone, and friends and supportive partners as crucial has been one of the most supportive units to be able to tell the truth together.” She to having children while pursuing academic outside of my department.” Reaching across expressed this wish in response to a ques- careers. In the April issue, Daniella Perry the campus continues to be crucial to CSW’s tion about who was at the forefront of the reported on the workshop and shared her mission. Now, we also reach across the women’s movement now. For her, leader- thoughts about the importance of getting country and around the globe through our ship was less an issue than community. -

CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: HAITI Last Update: 27 April 2011

WO RLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Global Task Force on Cholera Control CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: HAITI Last update: 27 April 2011 General Country Information: The Republic of Haiti is located in the western part of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago. It shares border with the Dominican Republic located in the Eastern part of the island. Haiti is divided in 10 departments further divided into 41 arrondissements. Port-au-Prince the capital, is the largest city of Haiti. The natives of Hispaniola known as Taino were invaded by Spanish settlers after the discovery of the island by Christopher Columbus in 1492. The French established a presence in the beginning of the 17 th century. In 1697, the western part of the island (which later became Haiti) was given to the French by Spain. The French colony quickly became wealthy due to profits from the sugar-related and coffee industries. Many African slaves were brought and significant environment degradation occurred during that time. Haiti gained its independence from France in 1804 after a revolt from the slaves. It was the first independent nation in Latin America. Haiti politics have gone through a lot of turmoil in the past 200 years. The country suffered 32 coups and has a long history of oppression by dictators. Long years of political instability left the country with huge social and economic problems. In January 2010, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti with an epicentre about 15 km southwest of the capital, Port-au-Prince leading to 220 000 deaths and the destruction of most of the infrastructure. -

Redalyc.Haiti One Year Later: Cuban Medical Team Draws On

MEDICC Review ISSN: 1555-7960 [email protected] Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba Estados Unidos Gorry, Conner Haiti One Year Later: Cuban Medical Team Draws on Experience and Partnerships MEDICC Review, vol. 13, núm. 1, 2011, pp. 52-55 Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba Oakland, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=437542077011 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative International Cooperation Report Haiti One Year Later: Cuban Medical Team Draws on Experience and Partnerships By Conner Gorry MA Nearly a year ago on a day like today—as people scrabbled for some charcoal to cook the evening meal, fetched their children from school, and sewed costumes for carnival—the ground began to shift. Buildings folded and houses crumbled. In the time it takes to read this paragraph, one of the most devastating earthquakes recorded in the hemisphere changed the Haitian landscape forever. Twelve months on, quake sur- vivors struggle to live, study, work, and worship within the parameters of this new landscape. They also struggle to stay healthy. “It’s important to be vigilant,” Dr Jorge Pérez, deputy director of Cuba’s Tropical Medicine Institute, told MEDICC Review in Port-au-Prince last March after assessing the post-quake health situation. “The epidemiological picture is going to get much more complicated.”[1] On October 21, nine months after the earth- quake that killed 250,000 and left over one million homeless, his prediction was borne out when the rst cases of cholera were con rmed by the National Public Health Laboratory in Port-au- C Gorry Prince.[2] By November 19, the outbreak had spread to all 10 Dr Adac Mendoza, Latin American Medical School graduate from departments across the country. -

Factsheet Cholera Epidemic Hispaniola

FACTSHEET CHOLERA EPIDEMIC HISPANIOLA 1. LATEST AVAILABLE FIGURES Haiti as of 04/06/11 Estimates Number of deaths in the country 5,386 Number of hospital admissions in the country 175,944 Total number of cases in the country 331,454 Report from the Ministry of Public Health, Epidemiological data, 8 June 2011 Dominican Republic as of 08/06/2011 Estimations Number of deaths in the country 36 Total number of cases in the country 1,685 Report from the Ministry of Public Health, Epidemiological data, 8 June 2011 Given the starting rainy season and the potential strong hurricane season, compounded with the overall weaknesses of sanitary infrastructure (latrines, waste management), it is feared that any new outbreaks could affect massively the population. For the past weeks, cholera figures seem to be again on the rise due to the rainy season. MSF confirms that most of their cholera treatment centres (CTCs) have reached their maximum capacity in the Western department. The European Centre for Disease Control is undertaking a new mission to Haiti and Dominican Republic from 8 to 17 June in order to assess the situation. Little patient at CTC in Ouanaminthe - © EC/ECHO 9 June 2011 1 FACTSHEET CHOLERA EPIDEMIC HISPANIOLA Source: MSPP Source: OMS/OPS 9 June 2011 2 FACTSHEET CHOLERA EPIDEMIC HISPANIOLA Dominican Republic The most recent epidemiological reports show that the rainy season might cause the epidemic to spread further. The total number of deaths has reached thirty-six, 40% of them over the last four weeks. Dominican Republic Ministry of Public Health – epidemiological week 20 2. -

Fact Sheets of the Paho/Who Technical Cooperation in Haiti 2010-2011

PAHO/WHO Technical Cooperation 2010-2011 “Now more than ever we must work together as ONE WHO and ONE UN for the benefit of the people of Haiti…we must try to look beyond this crisis and use this as an opportunity to build a sustainable and robust health system to protect the future generations of Haitians.” Mirta Roses Periago FACT SHEETS OF THE PAHO/WHO TECHNICAL COOPERATION IN HAITI 2010 - 2011 www.paho.org/hai http://www.paho.org/disasters http://haiti.humanitarianresponse.info www.paho.org/promess http://twitter.com/pahowho http://new.paho.org/blogs/haiti PAHO/WHO Technical Cooperation 2010-2011 INTRODUCTION Haitian Minister of Health, Dr. Alex Larsen, and PAHO Director, Dr. Mirta Roses Periago, during her visit to Haiti after the earthquake (Jan. 2010) Haiti, along with Bolivia, Guyana, Honduras, and Nicaragua, is one of the five priority countries of Pan American Health Organization-Regional Office for the Americas of the World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). PAHO Director, Dr. Mirta Roses Periago is a member of the Regional United Nations Development Group Team for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNDG LAC), which continues to consider Haiti as a priority on its agenda. PAHO/WHO also participates actively in the "Group of Friends of Haiti" created by the Organization of American States (OAS). In the aftermath of the earthquake which struck Haiti on January 12, 2010, PAHO/WHO responded immediately and was operational within three days. Critical information was gathered through the PAHO/WHO Emergency Operations Center (EOC). This facilitated the coordination of logistics and humanitarian aid efforts. -

Climate Change Resilience: the Case of Haiti EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

OXFAM RESEARCH REPORTS MARCH 2014 CLIMATE CHANGE RESILIENCE The case of Haiti BHAWAN SINGH/MARC J. COHEN University of Montréal/Oxfam America Natural and human-induced hazards (storms, floods, and droughts) have highly destructive impacts on buildings, land, water, livestock, and people in Haiti. The poorest Haitians, including low-income women, children, and elderly people, are especially vulnerable. There is already evidence of climate change, including higher mean temperatures and altered rainfall patterns. Without adaptation actions, climate change is likely to magnify the damaging effects of hazards and to increase poverty. Resilience-building measures include flood control, integrated river basin management, reforestation, promotion of wood-energy alternatives, adoption of new crop varieties and farming practices, reduction in cultivation of steep slopes, and creation of non-farm livelihood options. The prospects for climate change resilience are now intricately tied to post- earthquake reconstruction. As Haiti turns its attention to preparing for more disasters and rebuilds significant portions of its infrastructure, there is a real opportunity to integrate climate resilience into these efforts. But Haiti faces serious governance, capacity, and finance challenges. Capacity is weak because of a lack of sensitization to climate change, inadequate technical knowledge, and meagre finances. It is essential to disseminate information about climate change and variability and their impacts in order to press leaders to incorporate climate change resilience into development plans and policies. Oxfam Research Reports are written to share research results, to contribute to public debate and to invite feedback on development and humanitarian policy and practice. They do not necessarily reflect Oxfam policy positions. -

The Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: Where and How Did It Begin?

The Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: Where and how did it begin? Daniele Lantagne, G. Balakrish Nair, Claudio F. Lanata and Alejandro Cravioto Abstract In October 2010, cholera appeared in Haiti for the first time in nearly a century. The Secretary-General of the United Nations formed an Independent Panel to ‘‘investigate and seek to determine the source of the 2010 cholera outbreak in Haiti’’. To fulfill this mandate, the Panel conducted concurrent epidemiological, water and sanitation, and molecular analysis investigations. Our May 2011 findings indicated that the 2010 Haiti cholera outbreak was caused by bacteria introduced into Haiti as a result of human activity; more specifically by the contamination of the Meye Tributary System of the Artibonite River with a pathogenic strain of the current South Asian type Vibrio cholerae. Recommendations were presented to assist in preventing the future introduction and spread of cholera in Haiti and worldwide. In this chapter, we discuss both the results of the Independent Panel’s investigation and the context the report sat within; including background informa- tion, responses to the report’s release, additional research subsequent to our report, and the public health implications of the Haiti cholera epidemic. D. Lantagne (&) Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Tufts University, 200 College Avenue, Medford, MA 02155, USA e-mail: [email protected] G. Balakrish Nair Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, Haryana, India C. F. Lanata Instituo de Investigación Nutricional, The US Navy Medical Research Unit 6, Lima, Peru A. Cravioto International Vaccine Institute, Seoul, Korea Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology DOI: 10.1007/82_2013_331 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 D. -

Haiti – Dominican Republic: Environmental Challenges in the Border Zone

Haiti – Dominican Republic Environmental challenges in the border zone http://unep.org/Haiti/ This report was made possible by the generous contributions of the Government of Norway and the Government of Finland First published in June 2013 by the United Nations Environment Programme © 2013, United Nations Environment Programme United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Cover Image: © UNEP Photos: Unless otherwise credited, images in this report were taken by UNEP staff UNEP promotes Design and layout: Le Cadratin, Plagne, France environmentally sound practices globally and in its own activities. This publication is printed on recycled paper using eco-friendly practices. Our distribution policy aims to reduce UNEP’s carbon footprint. HAITi – DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Environmental challenges in the border zone United Nations Environment Programme Table of contents Foreword 4 Executive summary 6 Part 1 Background 10 1 Introduction 10 1.1 A challenging time for the border zone . -

Haiti and the Artibonite Valley

Haiti and the Artibonite Valley BY B. IRA JUDD Cl> Speaking at the opening session of a two-week seminar on farm management sponsored by the Food and Agricultural Organization in Manila on October 3, 1960, Cesar Fortich, Philippine Secretary of Agriculture said that poverty in Asia is ironical because " ... we possess lands so rich in potentiality but are utilized poorly". 2 Mr. Fortich continued by mentioning that rapidly increasing po pulation and under-production compounded the problem in Asia, "We were never so many in number as we are now in spite of war and poverty". He pointed out that Asia's population w:1s increasing faster than the increase in food supply. He urged Asian farmers to abandon their "tradition-bound primitive technology'' and their superstitions and adopt modem farming methods to offset the population explosion. He said there should be more mechanized farming, more diverse crops, more extensive use of fertilizers and a shift from subsistancc fam1ing to the production of more marketable crops. Much the same language could be used to describe the situation in Haiti. Haiti is a republic of the West Indies, occupying the west part of the island of Hispaniola (one of the Greater Antilles Islands), which it shares with the Dominican Republic. It has an area of 10,204 square miles, being sligthly smaller than the state of Maryland. The population is estimated to be 4,000,000. This means that there arc about 400 inhabitants per square mile, making Haiti one of the most densely populated areas in the western world. -

Report of The

Final Report of the Independent Panel of Experts on the Cholera Outbreak in Haiti Dr. Alejando Cravioto (Chair) International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh Dr. Claudio F. Lanata Instituto de Investigación Nutricional, and The US Navy Medical Research Unit 6, Lima, Peru Engr. Daniele S. Lantagne Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States Dr. G. Balakrish Nair National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases, Kolkata, India Page 2 of 32 Executive Summary Ten months after the devastating earthquake of January 12, 2010, cholera appeared in Haiti for the first time in nearly a century. The outbreak subsequently claimed over 4,500 lives, sickened almost 300,000 people, and continues to cause infections and deaths in Haiti. The source of the cholera has been controversial, with hypotheses that the pathogen that causes cholera (Vibrio cholerae) arrived into Haiti from the Gulf of Mexico due to tectonic shifts resulting from the earthquake, evolved into disease-causing strains from non-pathogenic strains naturally present in Haiti, or originated from a human host who inadvertently introduced the strain into the Haitian environment. A specific form of the third hypothesis, that soldiers deployed from a cholera- endemic country to the Mirebalais MINUSTAH camp were the source of the cholera, is a commonly held belief in Haiti. In order to determine the source of the outbreak definitively, the Secretary-General of the United Nations formed an Independent Panel of four international experts (the “Independent Panel”), with a mandate to “investigate and seek to determine the source of the 2010 cholera outbreak in Haiti”. To fulfill this mandate, concurrent epidemiological, water and sanitation, and molecular analysis investigations were carried out. -

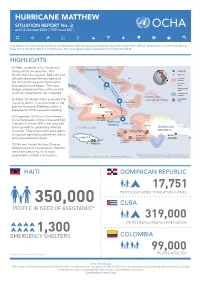

HURRICANE MATTHEW SITUATION REPORT No

HURRICANE MATTHEW SITUATION REPORT No. 2 as of 4 October 2016 (1700 hours EST) This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners and with inputs from official institutions. It covers the period from 3 to 4 October 2016 at 17:00 hours. The next report will be published on 5 October 2016. HIGHLIGHTS Forecast track and possible influence (as of 4 Oct 2016) • In Haiti, torrential rains, floods and BAHAMAS strong winds are reported. The Capital city Government has issued a Red alert and Major city officially requested the assistance of Hurricane warning the UN and its support mechanisms. 5 Oct, 2pm Hurricane Evacuations have begun. The main projected track watch Tropical storm bridge connecting Port-au-Prince with watch southern departments has collapsed. Tropical storm warning TURKS AND • Coordination In Cuba, the Government activated the CAICOS ISLANDS hubs 5 Oct, 2am “cyclonic alarm” in six provinces of the CUBA east for Hurricane Matthew, which is Holguin expected to hit the area this evening. Guantanamo • UN agencies, NGOs and the Interna- Santiago tional Federation of Red Cross and Red de Cuba Hurricane Crescent Societies (IFRC) are prepared 4 Oct, 5pm Matthew HAITI to bring relief to potentially affected Caribbean Sea DOMINICAN countries. They have mobilized experts Port-au-Prince REPUBLIC Jérémie to support national humanitarian teams (UNDAC) OCHA office Santo and pre-positioned stocks. JAMAICA MINUSTAH Domingo UNDAC Les Cayes UNDAC (UNDAC) • OCHA and United Nations Disaster Kingston Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) teams are preparing initial rapid The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map assessments in Haiti and Jamaica. -

CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: HAITI Last Update: 18 May 2011

WO Global Task Force on Cholera Control RLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: HAITI In 1697, the western part of the island (whi wealthy due to profits from the sugar-relat degradation occurred during that time. Haiti gained its independence from France in 1804 after a revolt Haiti politics have gone through a lot of turmoil in the past 20 oppression by dictators. Long years of polit magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti with an Last update: 18 May 2011 and the destruction of most of the infrastructure. Before the earthquake, many Haitian hous situation aggravated after the earthquake. A few have access to basic health care. The chronic shortage of more so apparent after the earthquake. Cholera history in the region: General Country Information: The last major cholera outbreak in Latin America start ch later became Haiti) was given to the French by Spain. The French colony quickly spread to many neighbouring countries. However Haiti and the Cari ed and coffee industries. Many African slaves were brought and significant environmeThe Republic of Haiti is located in the western part of pandemic. the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean Cholera Outbreak in 2010/2011: archipelago. It shares border with the Dominican Republic located in the East The first cholera cases in Haiti started to be reported on 14 Oc is divided in 10 departments further divided into 41 spread along the Artibonite river affecti arrondissements. Port-au-Prince the capital, is the case fatality rate in remote rural areas and areas with largest city of Haiti. was laboratory confirmed.